Introduction

A few weeks ago, I posted an article titled "Lightning-Fast Access Control Lists in C#", in which I described a solution for storing and querying permissions in a way that is database-schema agnostic. On the project that launched the article, I was not permitted to modify the database schema due to constraints outside my control.

Many readers followed up with this question:

Suppose you could change the database schema... What would it look like?

In this two-part article, I will answer that question in detail.

|

| In this first part:

- I'll start by describing my standard naming conventions for database tables and columns.

- Then I'll present code that helps to justify the conventions. Some of the conventions might seem unusual at first glance, and the code samples help to explain the rationale for them.

Then in the second part:

- I'll walk through the steps to create a full-fledged SQL Server database schema for a real-world application. The schema will include tables to support access control lists and nested user groups, as requested by readers of the original article and its followup article.

|

Just to be clear: this article will not discuss or include anything other than bare-metal SQL. So you won't find any C# discussed here; there is no Entity Framework, no data access layer, no unit tests, and no user interface. The focus here is on the database layer exclusively. Other layers in the technology stack for this solution can be explored in future articles.

Naming Conventions

Over the years, I have worked with countless different databases that follow countless different naming conventions (and sometimes no conventions at all).

I have also authored many different naming standards and guidelines, sometimes contradicting myself from one year to the next, based on what has proven itself and what hasn't.

Coding standards are hard to get right. We all know that, otherwise we'd all be using the same ones.

I have come to the conclusion that no convention is necessarily right or wrong. I have also come to the conclusion that a given standard might be "good" and still not necessarily fit every solution. Ultimately, you need to do what works best for your project, and the conventions I am about to describe may or may not be a good fit for you. If that's the case, then take whatever works and ignore the rest.

One warning in advance:

Some of my conventions fly in the face of popular wisdom, and others will irritate or abhor data modelling purists. What can I say, except that they come from background of experience in which a lot of blood, sweat, and tears has been shed. In itself, this doesn't miraculously make them good conventions, but they are battle-hardened, and that counts for some consideration, however small.

It is a pretty minimalist set - a classic Top 10 List - and I'll try to keep my commentary brief...

#1. Use Title Case

Use title case for database names, table names, and column names. I don't like a schema that shouts at me in upper case, and I don't like using underscores to separate words.

create table EMPLOYEE_MAILING_LIST

create table employee_mailing_list

create table EmployeeMailingList

Avoid blanks spaces, hyphens, and other special characters in your table and column names too.

#2. Prefix the Database Name to Indicate the Environment

You might have a local development environment, a test and QA environment, a demo environment, a training environment, and a live/production environment – all for the same application.

To keep from getting confused, prefix every database name with the name of the environment that it supports.

Database names like DemoAcme and LiveAcme are self-describing in this way. Self-descriptiveness is always a good quality in software architecture, and in this case it helps avoid stupid mistakes like this one:

use Acme;

go

delete from EmployeeMailingList;

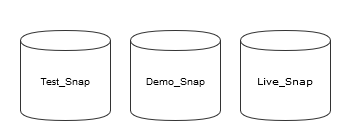

Here, I don't mind using an underscore to separate the environment name from the database name, so a typical application (call it "Snap" for the sake of example) has database instances with names that look like this:

#3. Use Schema Names to Organize Database Objects

Schema names are useful for organizing database objects into logical groups, especially when the database contains dozens (or hundreds) of tables and views.

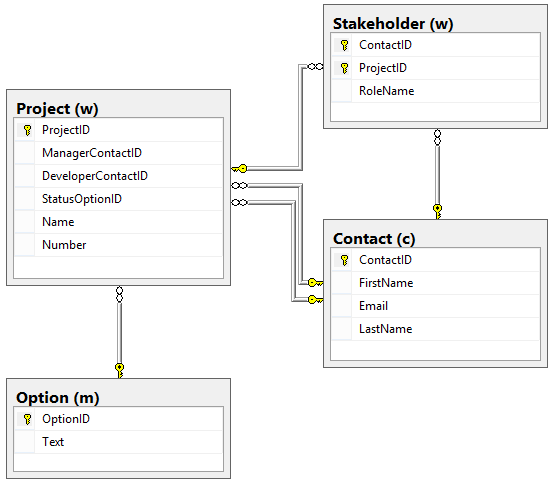

I use a one-letter abbreviation to keep schema names short and simple. For example:

- c = All database objects related to contact management

- e = Database objects related to email and message management

- m = Objects related to metadata

- o = Content-related objects

- w = Workflow-related objects

- x = Custom extensions to support specific one-offs, where reuse potential is slim to none

#4. Use Singular Nouns for Table Names

A singular noun is used to name every table. Most databases use plural nouns to name tables, so I break with tradition on this point. This is largely a matter of personal preference, but I do think singular nouns lend themselves to better alphabetic sorting of related names. Consider the following list of alphabetized table names:

InvoiceItemsInvoicePaymentsInvoiceReceiptsInvoicesInvoiceTaxes

That looks OK, but I think this looks better:

InvoiceInvoiceItemInvoicePaymentInvoiceReceiptInvoiceTax

The difference is subtle, and it won't matter to most DBAs and developers. It matters to me, but I obsess over a lot of little things. Obviously. :)

#5. Use Sensible Primary Keys

Every table must have a primary key. Use an auto-incrementing identity column whenever it makes sense to do so, but avoid spraying them blindly into every table throughout your database – especially when multi-column primary keys help to improve and enforce data integrity.

For example, suppose you want to enforce a business rule that says no two line items on the same invoice should reference the same product. That is, when a given product appears on an invoice, it should appear in one line item only. A composite primary key on InvoiceItem.InvoiceID and InvoiceItem.ProductID can be used to enforce this business rule, and then you don't have to worry about the potential for misbehaving code someday breaking this rule and compromising the integrity of your data.

#6. Use the Same Pattern for Identity-Enabled Primary Keys

When the primary key is a single-column, auto-incrementing, identity integer value, it is always named "EntityID". The "Entity" prefix matches the name of the table, and the "ID" suffix signifies an integer identifier.

This convention may be somewhat redundant, but it produces primary key names that are self-describing and unambiguous. Also, it helps to ensure the schema adheres to semantic rules in the ISO standard for SQL. (Refer to part 5 in ISO/IEC 11179.)

select ID from Hero

select HeroID from Hero

#7. Use Self-Describing Foreign-Key Column Names

A column that is intended to be a foreign key reference on another table follows this naming convention: AttributeEntityID.

- When

Entity does not match the name of the containing table, it identifies the column as a foreign key reference. Attribute qualifies the name of the property represented by the column. This is useful in a scenario that requires multiple foreign keys to the same primary table from the same foreign table.Entity is the name of the primary table being referenced.ID indicates an integer identifier.

Here are some examples:

- A foreign key column named

AuthorContactID stores the identifier for an Author; it references a primary table named Contact. - A foreign key column named

StatusOptionID stores the identifier for a Status; it references a table named Option. - A foreign key column named

AddressID stores the identifier for an address; it references a table named Address. The Attribute part of the column name is omitted in this example to show it is optional. When you have table that does not contain multiple foreign keys referencing the same primary table, this is a nice shorthand notation that still adheres to the convention.

Some of you will hate this foreign key naming convention even more than my primary key naming convention. (In fact, some of you are probably frothing at the mouth now; I can wait a moment while you count to ten and visit a washroom to take care of that...)

There is a method to my madness: I follow this convention because it produces foreign key column names that are entirely self-describing. Regardless of what you find in the data, and regardless of what constraints are actually defined, the intent is clear and unambiguous.

Here is an example of what this naming convention looks like in the context of a more detailed example:

When I inherit a database created by someone else, quite often it contains no referential integrity rules at all, and the person who created the database is long gone. So I'm left guessing where referential integrity was assumed by the developer, and it's not always obvious from reading the schema.

Pretend you have just been asked to solve a problem in a database you have never seen before. Your boss (or your customer) is frantic because users are howling for a solution. Everyone is looking at you because you're supposed to be the expert, and their last expert (who, as it happens, was the person who built the database) used up the last of their patience. They want a solution and they want it now.

And just to make life interesting, the database has no foreign key constraints defined in the schema. You know the problem somehow relates to employee data, and in one table you find a column named EmployeeID. So what is it? Is it an employee number? Is it a system-generated identifier? Is it an auto-number identity? Is it a foreign key? If it's a foreign key, what if there's no table named Employee? What is it intended to reference?

Unless there's technical documentation for the schema ("Ha! Good one, right?"), you might spend hours sifting through someone else's queries, stored procedures, data access code, business logic code, etc. etc.

Nobody should have to work that hard to answer a simple question, and I don't want to put anyone through that kind of pain and misery when they pick up one of my databases, so although my foreign key naming convention is a little ugly (I don't deny that) it eliminates guesswork, and that's a big point in its favour.

It has some added benefits, too, which I'll get into in a minute.

#9. Be Smart About NVARCHAR

Use the NVARCHAR data type only when you know you need it. If you need a column to store data in multiple character sets for multiple languages, then that is what Unicode (and NVARCHAR) is intended to do.

I have seen a lot of popular advice recommending developers store all text values in columns with an NVARCHAR data type. After all, Unicode supports every character set on the planet, so if you define an NVARCHAR column, then you can sleep peacefully forever after, knowing that it will hold anything and everything conceivable that might be input to it: English, French, German, Spanish, Ukrainian, Arabic, Hebrew, Japanese, Chinese, Swahili, Klingon, Tengwar…

When databases are relatively small, the popular advice holds: it really doesn't matter if you use VARCHAR or NVARCHAR. I was cavalier about this myself for years. And then I ran into a massive database that was chewing through disk space like a rabid dog. Its data files, transaction files, and backup files were enormous. The system had been running for more than a decade, the application it supported was used by English-language speakers only, the database contained English-language text only, there was no expectation its language requirements would change in the foreseeable future, and the database contained millions of records. The DBA was pulling out his hair in fistfulls. So I killed the Unicode option by replacing all NVARCHARs with VARCHARs, immediately decreasing the system's disk space consumption by 50 percent, with no loss of data, feature, or function. (And the DBA was able to preserve what little hair he had left.)

That said, if you need Unicode, then I use it. But if you don't need it: don't use it.

#10. Be Careful Around Mad MAX

Avoid using VARCHAR(MAX) and NVARCHAR(MAX) unless you know for certain that you need unlimited storage for a text-value column.

There are a variety of reasons for this, but I'll describe only the most important one:

While most DBAs already know this, many developers don't seem to realize the SQL Server query optimizer uses field size to determine its most efficient execution plan. When a field has no defined size, the optimizer becomes limited in its options, and database performance can suffer. And sometimes really suffer.

If performance isn't a concern (which might be true of a small database), then it's safe to disregard this. However, the performance difference between VARCHAR(MAX) and VARCHAR(300) can be an order of magnitude (or more) when the database is large.

Automatically Creating Foreign Key Constraints

Because these naming conventions encode the intent of the developer, they can be used to enable some pretty cool and interesting things. For example, they can be used to facilitate automated generation and validation of foreign key constraints.

I don't always remember to create foreign key constraints when I add new tables and columns to a database. And even if I do remember, I'm not always the only person who makes schema changes to a database, and others can forget too.

In this section, I'll describe the steps to arrive at a solution that enables a DBA or a developer to query the schema for foreign key constraints that should exist - and to create those constraints automatically.

First, you'll need some supporting database views to provide the necessary metadata.

Tables and Columns

The following view provides a basic wrapper around the INFORMATION_SCHEMA base tables. It includes everything you're likely to need when querying for metadata on tables:

CREATE VIEW m.MetaTable

AS

SELECT

TABLE_SCHEMA AS SchemaName

, CASE TABLE_SCHEMA

WHEN 'c' THEN 'Contact'

WHEN 'e' THEN 'Email'

WHEN 'm' THEN 'Metadata'

WHEN 'o' THEN 'Content'

WHEN 'w' THEN 'Workflow'

WHEN 'x' THEN 'Extension'

ELSE TABLE_SCHEMA

END AS SchemaDescription

, CASE TABLE_SCHEMA

WHEN 'c' THEN 'Orange'

WHEN 'e' THEN 'LimeGreen'

WHEN 'm' THEN 'AntiqueWhite4'

WHEN 'o' THEN 'DodgerBlue'

WHEN 'w' THEN 'Crimson'

WHEN 'x' THEN 'Purple4'

ELSE 'Black'

END AS SchemaColor

, TABLE_NAME AS TableName

FROM

INFORMATION_SCHEMA.TABLES

WHERE

TABLE_TYPE = 'BASE TABLE'

AND LOWER(TABLE_NAME) NOT IN (N'aspstatetempapplications',

N'aspstatetempsessions', N'dtproperties',

N'sysdiagrams');

Notice I use this opportunity to describe each schema/subsystem name and to give each schema a unique color-coding. Next, you'll need a similar wrapper to support queries on base table columns:

CREATE VIEW m.MetaColumn

AS

SELECT

T.SchemaName

, T.SchemaDescription

, T.SchemaColor

, T.TableName

, COLUMN_NAME AS ColumnName

, DATA_TYPE AS DataType

, CHARACTER_MAXIMUM_LENGTH AS MaximumLength

, CAST(CASE WHEN IS_NULLABLE = 'YES' THEN 0

WHEN IS_NULLABLE = 'NO' THEN 1

ELSE NULL

END AS BIT) AS IsRequired

, CAST(CASE WHEN COLUMNPROPERTY(OBJECT_ID(T.SchemaName + '.' + T.TableName),

COLUMN_NAME, 'IsIdentity') = 1 THEN 1

ELSE 0

END AS BIT) AS IsIdentity

, C.ORDINAL_POSITION AS OrdinalPosition

FROM

INFORMATION_SCHEMA.COLUMNS AS C

INNER JOIN m.MetaTable AS T

ON C.TABLE_NAME = T.TableName

AND C.TABLE_SCHEMA = T.SchemaName;

Foreign Keys

You'll also want a metadata view that returns the set of foreign key constraints actually defined in the database. This is a wrapper around SQL Server’s system tables:

CREATE VIEW m.MetaForeignKeyConstraint

AS

SELECT OBJECT_SCHEMA_NAME(fk.parent_object_id) AS ForeignSchemaName

, ForeignTable.SchemaDescription AS ForeignSchemaDescription

, OBJECT_NAME(fk.parent_object_id) AS ForeignTableName

, cpa.name AS ForeignColumnName

, OBJECT_SCHEMA_NAME(fk.referenced_object_id) AS PrimarySchemaName

, PrimaryTable.SchemaDescription AS PrimarySchemaDescription

, OBJECT_NAME(fk.referenced_object_id) AS PrimaryTableName

, cref.name AS PrimaryColumnName

, fk.name AS ConstraintName

FROM sys.foreign_keys fk

INNER JOIN sys.foreign_key_columns fkc ON fkc.constraint_object_id = fk.object_id

INNER JOIN sys.columns cpa ON fkc.parent_object_id = cpa.object_id

AND fkc.parent_column_id = cpa.column_id

INNER JOIN sys.columns cref ON fkc.referenced_object_id = cref.object_id

AND fkc.referenced_column_id = cref.column_id

INNER JOIN m.MetaTable AS PrimaryTable

ON OBJECT_SCHEMA_NAME(fk.referenced_object_id) = PrimaryTable.SchemaName

AND OBJECT_NAME(fk.referenced_object_id) = PrimaryTable.TableName

INNER JOIN m.MetaTable AS ForeignTable

ON OBJECT_SCHEMA_NAME(fk.parent_object_id) = ForeignTable.SchemaName

AND OBJECT_NAME(fk.parent_object_id) = ForeignTable.TableName;

Paired with this, you'll need a view that tells you what foreign key constraints should exist in the database, based on the table and column naming conventions:

CREATE VIEW m.MetaForeignKey

AS

WITH CTE

AS (SELECT

c.SchemaName AS ForeignSchemaName

, c.SchemaDescription AS ForeignSchemaDescription

, c.SchemaColor AS ForeignSchemaColor

, c.TableName AS ForeignTableName

, c.ColumnName AS ForeignColumnName

, c.IsRequired AS ForeignColumnRequired

, t.SchemaName AS PrimarySchemaName

, t.SchemaDescription AS PrimarySchemaDescription

, t.SchemaColor AS PrimarySchemaColor

, t.TableName AS PrimaryTableName

, t.TableName + 'ID' AS PrimaryColumnName

, CASE WHEN fk.PrimaryColumnName IS NOT NULL THEN CAST(1 AS BIT)

ELSE CAST(0 AS BIT)

END AS IsEnforced

, c.TableName + '_' + c.ColumnName AS UniqueName

, ROW_NUMBER() OVER (ORDER BY c.TableName, c.ColumnName) AS RowNumber

FROM

m.MetaColumn AS c

INNER JOIN m.MetaTable AS t

ON c.ColumnName LIKE '%' + t.TableName + 'ID'

AND (c.TableName <> t.TableName

OR c.ColumnName = 'Parent' + t.TableName + 'ID'

)

LEFT JOIN m.MetaForeignKeyConstraint AS fk

ON fk.ForeignSchemaName = c.SchemaName

AND fk.ForeignTableName = c.TableName

AND fk.ForeignColumnName = c.ColumnName

AND fk.PrimaryTableName = t.TableName

WHERE

c.ColumnName LIKE '%ID'

)

SELECT

*

FROM

CTE AS A

WHERE

NOT EXISTS ( SELECT

*

FROM

CTE AS B

WHERE

A.UniqueName = B.UniqueName

AND A.RowNumber <> B.RowNumber

AND B.PrimaryTableName LIKE '%' + A.PrimaryTableName );

The IsEnforced column tells you whether or not a physical constraint exists in the database, and the UniqueName column tells you what the name of that constraint ought to be - regardless of whether or not the constraint actually exists in the database. That last bit is crucial.

Dropping Foreign Key Constraints

Now you can use results from the above views to programmatically drop all the foreign key constraints in the database. This is handy when you're bulk-loading data or running a script that makes extensive changes to the schema.

CREATE PROCEDURE m.DropForeignKeyConstraints

AS

BEGIN

DECLARE X CURSOR

FOR

SELECT

ForeignSchemaName + '.[' + ForeignTableName + ']'

, ConstraintName

FROM

m.MetaForeignKeyConstraint;

DECLARE @TableName NVARCHAR(128);

DECLARE @ConstraintName NVARCHAR(MAX);

OPEN X;

FETCH NEXT FROM X INTO @TableName, @ConstraintName;

WHILE @@FETCH_STATUS = 0

BEGIN

DECLARE @SqlStatement NVARCHAR(MAX) = 'ALTER TABLE ' + @TableName

+ ' DROP CONSTRAINT ' + @ConstraintName;

EXEC sp_executesql @SqlStatement;

FETCH NEXT FROM X INTO @TableName, @ConstraintName;

END;

CLOSE X;

DEALLOCATE X;

END;

Creating Foreign Key Constraints

Next is the magic we have been working toward. What we want is a stored procedure that automatically creates all of the foreign key constraints that should exist in the database, based on the naming conventions used for its tables and columns.

For example, if we have a column named OccupationID in a table named Employment, then we want to enforce two assumptions:

- A table named

Occupation exists with a primary key named OccupationID, and - A foreign key constraint exists between this column in the

Employment table and the Occupation table.

The code is surprisingly lightweight:

CREATE PROCEDURE m.CreateForeignKeyConstraints

AS

BEGIN

DECLARE X CURSOR

FOR

SELECT DISTINCT

ForeignSchemaName + '.[' + ForeignTableName + ']'

, ForeignColumnName

, 'FK_' + SUBSTRING(UniqueName, 1, LEN(UniqueName) - 2)

, PrimarySchemaName + '.[' + PrimaryTableName + '] (' + PrimaryColumnName + ')'

FROM

m.MetaForeignKey;

DECLARE @TableName NVARCHAR(128);

DECLARE @ColumnName NVARCHAR(128);

DECLARE @ConstraintName NVARCHAR(128);

DECLARE @PK NVARCHAR(128);

OPEN X;

FETCH NEXT FROM X INTO @TableName, @ColumnName, @ConstraintName, @PK;

WHILE @@FETCH_STATUS = 0

BEGIN

DECLARE @SqlStatement NVARCHAR(MAX) = 'ALTER TABLE ' + @TableName

+ ' ADD CONSTRAINT ' + @ConstraintName + ' FOREIGN KEY ('

+ @ColumnName + ') REFERENCES ' + @PK;

EXEC sp_executesql @SqlStatement;

FETCH NEXT FROM X INTO @TableName, @ColumnName, @ConstraintName, @PK;

END;

CLOSE X;

DEALLOCATE X;

END;

Now you can drop and re-create all your foreign key constraints with just two lines of T-SQL, and know for certain that all your referential integrity rules are in place.

EXEC m.DropForeignKeyConstraints;

EXEC m.CreateForeignKeyConstraints;

Because your intentions were encoded into your writing of the schema, those intentions can be enforced by the schema. As Pharoah said in that old classic film: "So let it be written, so let it be done." This is the kind of simplicity and certainty you want in a database.

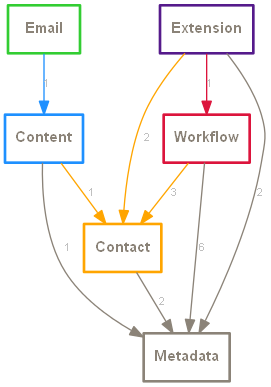

Database Structure Visualization

Combined, the naming conventions and the metadata views also enable automated visualization of the database structure.

Schemas

For example, we can use simple query results as input to GraphViz for visualizing the dependencies between subsystems. This is especially useful if you're looking for circular dependencies between schemas and tables.

SELECT DISTINCT

SchemaDescription + ' [color="' + SchemaColor + '"];' AS Vertex

FROM m.MetaTable

WHERE SchemaName NOT IN ('dbo', 'x')

ORDER BY SchemaDescription + ' [color="' + SchemaColor + '"];'

SELECT ForeignSchemaDescription + ' -> ' + PrimarySchemaDescription

+ ' [color="' + fk.PrimarySchemaColor + '", label="'

+ CAST(COUNT(*) AS VARCHAR) + '"];' AS Edge

FROM m.MetaForeignKey AS fk

WHERE ForeignSchemaDescription <> PrimarySchemaDescription

AND ForeignSchemaName NOT IN ('dbo', 'x')

GROUP BY ForeignSchemaDescription

, PrimarySchemaDescription

, PrimarySchemaColor

ORDER BY ForeignSchemaDescription

, PrimarySchemaDescription;

The DOT language syntax looks like this:

digraph

{

node [fontname="Arial Bold", fontsize=11, shape=box, fontcolor=AntiqueWhite4, style=bold];

edge [fontname=arial, fontsize=8, fontcolor=gray];

Contact [color=Orange];

Email [color=LimeGreen];

Metadata [color=AntiqueWhite4];

Content [color=DodgerBlue];

Workflow [color=Crimson];

Extension [color=Purple4];

Contact -> Metadata [color=AntiqueWhite4, label=2];

Email -> Content [color=DodgerBlue, label=1];

Content -> Metadata [color=AntiqueWhite4, label=1];

Content -> Contact [color=Orange, label=1];

Workflow -> Metadata [color=AntiqueWhite4, label=6];

Workflow -> Contact [color=Orange, label=3];

Extension -> Metadata [color=AntiqueWhite4, label=2];

Extension -> Workflow [color=Crimson, label=1];

Extension -> Contact [color=Orange, label=2];

}

... which produces a color-coded graph that looks like this:

Notice the cardinality label on each edge. This shows the number of foreign keys in the dependency between two subsystems, and this gives you a sense of its 'weight'.

For example, you can see from the diagram that we have 6 foreign key references between tables in the Workflow schema and tables in the Metadata schema. This is suggests the entities in the Workflow and Metadata subsystems are more tightly coupled than any other two subsystems.

The diagram also shows there are no dependency cycles between subsystems.

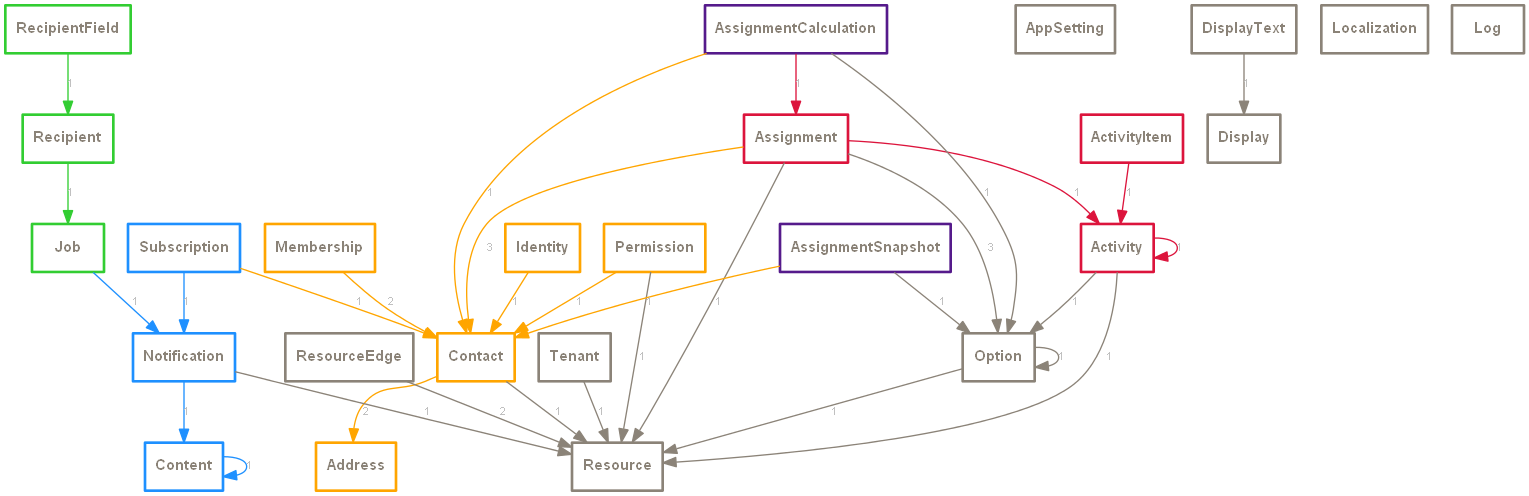

Tables

It's easy to spend hours fiddling with diagrams in SQL Server Management Studio, Visual Studio, Visio, Gliffy, and any number of other diagramming tools. I enjoy that sort of thing, but I don't often have time for it.

Alternatively, you can knock out a color-coded diagram in about 15 seconds, knowing for certain that it models the structure of your database exactly.

Here's the SQL:

SELECT TableName + ' [color=' + SchemaColor + '];' AS Vertex

FROM m.MetaTable AS T

WHERE EXISTS ( SELECT *

FROM m.MetaForeignKey

WHERE ForeignTableName = T.TableName

OR PrimaryTableName = T.TableName )

AND SchemaName NOT IN ('dbo', 'x')

ORDER BY TableName;

SELECT fk.ForeignTableName + ' -> ' + fk.PrimaryTableName + ' [color='

+ fk.PrimarySchemaColor + ', label="' + CAST(COUNT(*) AS VARCHAR)

+ '"];' AS Edge

FROM m.MetaForeignKey AS fk

WHERE ForeignTableName <> PrimaryTableName

AND ForeignSchemaName NOT IN ('dbo', 'x')

GROUP BY ForeignTableName

, PrimaryTableName

, PrimarySchemaColor

ORDER BY ForeignTableName

, PrimaryTableName;

... and here's the DOT syntax:

digraph

{

node [fontname="Arial Bold", fontsize=11, shape=box, fontcolor=AntiqueWhite4, style=bold];

edge [fontname=arial, fontsize=8, fontcolor=gray];

Address [color=Orange];

Contact [color=Orange];

Identity [color=Orange];

Membership [color=Orange];

Permission [color=Orange];

Job [color=LimeGreen];

Recipient [color=LimeGreen];

RecipientField [color=LimeGreen];

AppSetting [color=AntiqueWhite4];

Display [color=AntiqueWhite4];

DisplayText [color=AntiqueWhite4];

Localization [color=AntiqueWhite4];

Log [color=AntiqueWhite4];

Option [color=AntiqueWhite4];

Resource [color=AntiqueWhite4];

ResourceEdge [color=AntiqueWhite4];

Tenant [color=AntiqueWhite4];

Content [color=DodgerBlue];

Notification [color=DodgerBlue];

Subscription [color=DodgerBlue];

Activity [color=Crimson];

ActivityItem [color=Crimson];

Assignment [color=Crimson];

AssignmentCalculation [color=Purple4];

AssignmentSnapshot [color=Purple4];

Contact -> Address [color=Orange, label=2];

Contact -> Resource [color=AntiqueWhite4, label=1];

Identity -> Contact [color=Orange, label=1];

Membership -> Contact [color=Orange, label=2];

Permission -> Contact [color=Orange, label=1];

Permission -> Resource [color=AntiqueWhite4, label=1];

Job -> Notification [color=DodgerBlue, label=1];

Recipient -> Job [color=LimeGreen, label=1];

RecipientField -> Recipient [color=LimeGreen, label=1];

DisplayText -> Display [color=AntiqueWhite4, label=1];

Option -> Option [color=AntiqueWhite4, label=1];

Option -> Resource [color=AntiqueWhite4, label=1];

ResourceEdge -> Resource [color=AntiqueWhite4, label=2];

Tenant -> Resource [color=AntiqueWhite4, label=1];

Content -> Content [color=DodgerBlue, label=1];

Notification -> Content [color=DodgerBlue, label=1];

Notification -> Resource [color=AntiqueWhite4, label=1];

Subscription -> Contact [color=Orange, label=1];

Subscription -> Notification [color=DodgerBlue, label=1];

Activity -> Option [color=AntiqueWhite4, label=1];

Activity -> Activity [color=Crimson, label=1];

Activity -> Resource [color=AntiqueWhite4, label=1];

ActivityItem -> Activity [color=Crimson, label=1];

Assignment -> Activity [color=Crimson, label=1];

Assignment -> Option [color=AntiqueWhite4, label=3];

Assignment -> Contact [color=Orange, label=3];

Assignment -> Resource [color=AntiqueWhite4, label=1];

AssignmentCalculation -> Option [color=AntiqueWhite4, label=1];

AssignmentCalculation -> Assignment [color=Crimson, label=1];

AssignmentCalculation -> Contact [color=Orange, label=1];

AssignmentSnapshot -> Option [color=AntiqueWhite4, label=1];

AssignmentSnapshot -> Contact [color=Orange, label=1];

}

... and here's the graph:

Next Up: Building the Database

Now that we've covered naming conventions, foreign keys, and metadata, we have the foundation for the database we're about to build. That is the focus of the next article, which I will post here soon.

History

- December 17, 2015 - First draft

- December 18, 2015 - Fixed minor typos and added source code download

- December 19, 2015 - Fixed minor typos and improved diagrams

- December 21, 2015 - Fixed minor typos

- December 29, 2015 - Revised the naming conventions for primary and foreign keys based on excellent comments from CodeProject community member Jörgen Andersson

- December 30, 2015 - Modified code snippets as per editor feedback; deleted unreferenced images; replaced thumbnail image