This is an article about using AppDomains to load and unload assemblies that also explores the nuances of working with application domains.

Table of Contents

There are a lot of posts and articles out there about using AppDomain to load and unload assemblies, but I haven't found one place that puts it all together into something that makes sense as well as exploring the nuances of working with application domains, hence the reason for this article.

For myself, the purpose for loading and unloading assemblies at runtime is so that I can hot-swap one assembly with another one without shutting down the whole application. This is important when running applications like a web server or an ATM, or you want to preserve application state without having to persist everything, restart the application, and then restore the state. Even if it means that the application is momentarily (for a few hundred milliseconds) unresponsive, this is far better than having to tear down the entire application, return to the Windows screen, and restart it.

Getting a working example up and running isn't that difficult. The main tricks are:

- Using the

Serializable attribute on classes that you want to expose in the assembly being runtime loaded. - Deriving exposed classes from

MarshalByRefObject (this can cause some interesting pain points). - Using a separate assembly that is shared between your application and the runtime loaded assembly to define an interface through which your application calls methods and properties in the exposed runtime loaded classes.

The nuances occur primarily in the use of MarshalByRefObject with regards to how instance parameters are passed, as this determines whether the instance is passed by value or by reference. More on this later.

To demonstrate loading / unloading assemblies in their own application domain, we need three projects:

- A project defining the interface shared between the first two projects

- A project for the assembly to be loaded

- The main application project

We'll start with a very simple interface:

using System;

namespace CommonInterface

{

public interface IPlugIn

{

string Name { get; }

void Initialize();

}

}

Here, we'll demonstrate calling a method and reading a property.

The second project, the assembly to be loaded, contains one class that implements the plug-in interface:

using System;

using CommonInterface;

namespace PlugIn1

{

[Serializable]

public class PlugIn : MarshalByRefObject, IPlugIn

{

private string name;

public string Name { get { return name; } }

public void Initialize()

{

name = "PlugIn 1";

}

}

}

Note that the class is marked as Serializable and derives from MarshalByRefObject. More on this later.

The third project is the application itself. Here's the core piece:

using System;

using System.Reflection;

using CommonInterface;

namespace AppDomainTests

{

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

AppDomain appDomain1 = CreateAppDomain("PlugIn1");

IPlugIn plugin1 = InstantiatePlugin("PlugIn1", appDomain1);

plugin1.Initialize();

Console.WriteLine(plugin1.Name+"\r\n");

UnloadPlugin(appDomain1);

TestIfUnloaded(plugin1);

}

}

}

This code:

- loads the plug-in assembly into an application domain separate from the main application domain

- instantiates the class implementing

IPlugIn - initializes the class

- reads the value of the

Name property - unloads the assembly

- verifies that after the assembly is unloaded, an

AppDomainUnloadedException is thrown

Three helper methods are used.

static AppDomain CreateAppDomain(string dllName)

{

AppDomainSetup setup = new AppDomainSetup()

{

ApplicationName = dllName,

ConfigurationFile = dllName + ".dll.config",

ApplicationBase = AppDomain.CurrentDomain.BaseDirectory

};

AppDomain appDomain = AppDomain.CreateDomain(

setup.ApplicationName,

AppDomain.CurrentDomain.Evidence,

setup);

return appDomain;

}

static IPlugIn InstantiatePlugin(string dllName, AppDomain domain)

{

IPlugIn plugIn = domain.CreateInstanceAndUnwrap(dllName, dllName + ".PlugIn") as IPlugIn;

return plugIn;

}

static void TestIfUnloaded(IPlugIn plugin)

{

bool unloaded = false;

try

{

Console.WriteLine(plugin.Name);

}

catch (AppDomainUnloadedException)

{

unloaded = true;

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

Console.WriteLine(ex.Message);

}

if (!unloaded)

{

Console.WriteLine("It does not appear that the app domain successfully unloaded.");

}

}

This test verifies that, if we try to access methods (or properties, which are actually methods) of the plugin once it is unloaded, that we get an AppDomainUnloadedException.

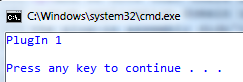

When we run this test, we see:

And we note that there are no other errors produced, so we know that the custom application domain is unloading the assembly correctly -- in other words, the plug-in assembly didn't get attached to our application's app-domain.

When you create an application domain (and one is created for you when you launch any .NET program), you're creating an isolated process (usually called the "program") that manages static variables, additional required assemblies, and so forth. Application domains do not share anything. .NET uses "remoting" to communicate between application domains, but it can only do this if the classes that need to be shared between domains are marked as serializable, otherwise the remoting mechanism will not serialize the class.

Of course, this might seem strange when you're instantiating a class -- why does it need to be marked as serializable when we're only calling methods (even properties are syntactical sugar for get/set methods)? Of course, .NET doesn't "know" that you're only accessing methods -- you could very well be accessing fields as well, and therefore the class that you instantiate in the plug-in assembly must be serializable.

Microsoft's documentation on AppDomain remoting states:

This topic is specific to a legacy technology that is retained for backward compatibility with existing applications and is not recommended for new development. Distributed applications should now be developed using the Windows Communication Foundation (WCF).

The problem with this is that WCF is not a lightweight solution -- the setup and configuration of distributed applications using WCF is complicated. You get an idea of the issues involved reading this. Certainly for this article, WCF is outside of the realm of "keep it simple, stupid."

(A very interesting article on generic WCF hosting is here.)

This is a fun one. Let's add a method that lists the loaded assemblies in our application's AppDomain:

static void PrintLoadedAssemblies()

{

Assembly[] assys = AppDomain.CurrentDomain.GetAssemblies();

Console.WriteLine("----------------------------------");

foreach (Assembly assy in assys)

{

Console.WriteLine(assy.FullName.LeftOf(','));

}

Console.WriteLine("----------------------------------");

}

And we'll call PrintLoadedAssemblies:

- before loading the plug-in in its own

AppDomain - after we load the plug-in

- and after we unload the

AppDomain

static void Main(string[] args)

{

PrintLoadedAssemblies();

AppDomain appDomain1 = CreateAppDomain("PlugIn1");

IPlugIn plugin1 = InstantiatePlugin("PlugIn1", appDomain);

PrintLoadedAssemblies();

plugin1.Initialize();

Console.WriteLine(plugin1.Name+"\r\n");

UnloadPlugin(appDomain1);

PrintLoadedAssemblies();

TestIfUnloaded(plugin1);

}

Here's the result:

Notice that the plug-in assembly never shows up in this list! What MarshalByRefObject is doing is passing, not the actual object, but a proxy of our object, back to the main application. By using a proxy, the plug-in assembly never loads into our application's AppDomain.

Now let's change our plug-in so that it doesn't derive from MarshalByRefObject:

public class PlugIn : IPlugIn

...etc...

and run the test again:

Notice three things:

- The plug-in suddenly appears in our application's list of assemblies.

- The

AppDomain holding (supposedly) our plug-in actually isn't -- unloading it does not remove the assembly because the assembly is in our application's AppDomain! - We can still access the object after supposedly unloading the assembly.

This is happening because the plug-in class is no longer being returned to us via a proxy -- instead, it is being returned "by value", and in the case of a class instance, this means that the object, in order to be deserialized when crosses the AppDomain, is instantiated on "our side" of the AppDomain.

One way to think about MarshalByRefObject is that, by deriving from this base class, you are creating an "anchor" between the two application domain worlds, in which there is a common, known, implementation, similar to how interfaces "anchor" classes with a common behavior, but in a way that the actual implementation can vary.

Let's explore this behavior of MarshalByRefObject a bit more. First, we'll define a "Thing" class, derived from MarshalByRefObject:

using System;

namespace AThing

{

[Serializable]

public class Thing : MarshalByRefObject

{

public string Value { get; set; }

public Thing(string val)

{

Value = val;

}

}

}

and we'll add some behavior to our plug-in interface:

public interface IPlugIn

{

string Name { get; }

void Initialize();

void SetThings(List<Thing> things);

void PrintThings();

}

Our new plug-in implementation now looks like this:

[Serializable]

public class PlugIn : MarshalByRefObject, IPlugIn

{

private string name;

private List<Thing> things;

public string Name { get { return name; } }

public void Initialize()

{

name = "PlugIn 1";

}

public void SetThings(List<Thing> things)

{

this.things = things;

}

public void PrintThings()

{

foreach (Thing thing in things)

{

Console.WriteLine(thing.Value);

}

}

}

Let's see what happens when we pass in a List<Thing> and then change the collection itself as well as an item in the collection (remember, Thing is derived from MarshalByRefObject). Can you predict what will happen? Here's the code:

static void Demo3()

{

PrintLoadedAssemblies();

AppDomain appDomain1 = CreateAppDomain("PlugIn1");

IPlugIn plugin1 = InstantiatePlugin("PlugIn1", appDomain1);

appDomain1.DomainUnload += OnDomainUnload;

PrintLoadedAssemblies();

plugin1.Initialize();

Console.WriteLine(plugin1.Name+"\r\n");

List<Thing> things = new List<Thing>() { new Thing("A"), new Thing("B"), new Thing("C") };

plugin1.SetThings(things);

plugin1.PrintThings();

Console.WriteLine("\r\n");

things[0].Value = "AA";

things.Add(new Thing("D"));

plugin1.PrintThings();

Console.WriteLine("\r\n");

UnloadPlugin(appDomain1);

PrintLoadedAssemblies();

TestIfUnloaded(plugin1);

}

Fascinating!

Notice that:

- the collection doesn't change

- but the value of "

A" has been changed to "AA"

Why?

List<T> is not derived from MarshalByRefObject, so it is passed by value (as in, serialized) when it crosses the AppDomain.- The actual

Thing entries, where Thing derives from MarshalByRefObject, are passed by reference, and so changing the value on one side of the AppDomain affects the other side.

What happens if we do not derive Thing from MarshalByRefObject?

[Serializable]

public class Thing

{

public string Value { get; set; }

public Thing(string val)

{

Value = val;

}

}

The collection entry "A" did not change to "AA", because now Thing is also being passed by value!

Let's put the MarshalByRefObject back as the base class to Thing:

public class Thing : MarshalByRefObject

and add a method (and its interface) in the plug-in:

public void ChangeThings()

{

things[2].Value = "Mwahaha!";

}

We'll write a short test:

static void Demo5()

{

AppDomain appDomain1 = CreateAppDomain("PlugIn1");

IPlugIn plugin1 = InstantiatePlugin("PlugIn1", appDomain1);

List<Thing> things = new List<Thing>() { new Thing("A"), new Thing("B"), new Thing("C") };

plugin1.SetThings(things);

plugin1.ChangeThings();

foreach (Thing thing in things)

{

Console.WriteLine(thing.Value);

}

}

and the result is:

Oh my -- is this the intended behavior, that our objects are mutable across application domains? Maybe, maybe not!

Let's try one more thing -- we'll dynamically load an assembly in the plug-in to verify that the assembly is loaded into the plug-in's AppDomain, not ours. Here's the full plug-in class (I'm not going to bother showing the interface):

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

using System.Reflection;

using AThing;

using CommonInterface;

namespace PlugIn1

{

[Serializable]

public class PlugIn : MarshalByRefObject, IPlugIn

{

private string name;

private List<Thing> things;

public string Name { get { return name; } }

public void Initialize()

{

name = "PlugIn 1";

}

public void SetThings(List<Thing> things)

{

this.things = things;

}

public void PrintThings()

{

foreach (Thing thing in things)

{

Console.WriteLine(thing.Value);

}

}

public void PrintLoadedAssemblies()

{

Helpers.PrintLoadedAssemblies();

}

public void LoadRuntimeAssembly()

{

IDynamicAssembly dassy = DynamicAssemblyLoad();

dassy.HelloWorld();

}

private IDynamicAssembly DynamicAssemblyLoad()

{

Assembly assy = AppDomain.CurrentDomain.Load("DynamicallyLoadedByPlugin");

Type t = assy.GetTypes().SingleOrDefault(assyt => assyt.Name == "LoadMe");

return Activator.CreateInstance(t) as IDynamicAssembly;

}

}

}

And here's our test:

static void Demo4()

{

AppDomain appDomain1 = CreateAppDomain("PlugIn1");

IPlugIn plugin1 = InstantiatePlugin("PlugIn1", appDomain1);

Console.WriteLine("Our assemblies:");

Helpers.PrintLoadedAssemblies();

plugin1.LoadRuntimeAssembly();

Console.WriteLine("Their assemblies:");

plugin1.PrintLoadedAssemblies();

}

We get what we expect, which is that the dynamically loaded assembly, loaded by the plug-in, is in its AppDomain, not ours:

It is not trivial to work with application domains, especially when implementing hot-swappable modules. You need to consider:

If not, you will not be able to transport an instance of your class (either by value or by reference) across an AppDomain.

For example, the List<T> generic collection class is -- notice the Syntax section of the documentation. But is the generic <T> serializable? Other classes, such as SqlConnection, are not serializable. You need to know exactly what you are intending to pass across the application domain.

This has significant implications in your application design -- if you expect that changes to objects by the application, in any AppDomain, will be affect the instances of those "same" objects in other AppDomains, you have to derive your classes from MarshalByRefObject. However, this behavior can be dangerous and have side-effects as the objects are mutable across application domains.

Another important factor is, can you actually pass by reference? We saw that List<T> cannot be passed by reference because it doesn't derive from MarshalByRefObject. Expecting that an object with all its glorious mutability behaves the same way once we pass it across an application domain is a very very dangerous expectation unless you know exactly what the definition of the class is, and all the class members, and their members, etc.

If you can't derive from MarshalByRefObject but you want your object to be mutable across application domains, then you have to write a wrapper that implements, via an interface, the behaviors that you want. Consider this wrapper:

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using AThing;

namespace CommonInterface

{

public class MutableListOfThings : MarshalByRefObject

{

private List<Thing> things;

public int Count { get { return things.Count; } }

public MutableListOfThings()

{

things = new List<Thing>();

}

public void Add(Thing thing)

{

things.Add(thing);

}

public Thing this[int n]

{

get { return things[n]; }

set { things[n] = value; }

}

}

}

And a few additional methods in our plugin that work with MutableListOfThings:

public void SetThings(MutableListOfThings mutable)

{

this.mutable = mutable;

}

public void PrintMutableThings()

{

for (int i=0; i<mutable.Count; i++)

{

Console.WriteLine(mutable[i].Value);

}

}

public void ChangeMutableThings()

{

mutable[2].Value = "Mutable!";

mutable.Add(new Thing("D"));

}

and our test method:

static void Demo6()

{

MutableListOfThings mutable = new MutableListOfThings();

AppDomain appDomain1 = CreateAppDomain("PlugIn1");

IPlugIn plugin1 = InstantiatePlugin("PlugIn1", appDomain1);

plugin1.SetThings(mutable);

mutable.Add(new Thing("A"));

mutable.Add(new Thing("B"));

mutable.Add(new Thing("C"));

plugin1.PrintMutableThings();

plugin1.ChangeMutableThings();

Console.WriteLine("\r\n");

for (int i = 0; i < mutable.Count; i++)

{

Console.WriteLine(mutable[i].Value);

}

}

Now look at what happens:

Why does this work? It works because MutableListOfThings is passed by reference, so even though it contains an object List<Thing> that is not passed by reference, we are always manipulating the list through our single reference.

Of course, things go really wonky when Thing is not derived from MarshalByRefObject:

Now, Thing is passed by value, so the entry for "C" did not change, but changes to the list (adding "D"), encapsulated by our wrapper class, is seen across both domains!

This should help (or hinder) the realization that working across application domains is not trivial.

Each assembly that you wish to swap out at runtime needs to be loaded in its own application domain so you're not accidentally unloading application domains with other assemblies that should not be removed. This makes for a lot of application domains that need to be managed!

Here's the test code:

static void Demo7()

{

DateTime now = DateTime.Now;

int n = 0;

IPlugIn plugin1 = new PlugIn1.PlugIn();

List<Thing> things = new List<Thing>() { new Thing("A"), new Thing("B"), new Thing("C") };

while ((DateTime.Now - now).TotalMilliseconds < 1000)

{

plugin1.SetThings(things);

++n;

}

Console.WriteLine("Called SetThings {0} times.", n);

AppDomain appDomain1 = CreateAppDomain("PlugIn1");

plugin1 = InstantiatePlugin("PlugIn1", appDomain1);

now = DateTime.Now;

n = 0;

while ((DateTime.Now - now).TotalMilliseconds < 1000)

{

plugin1.SetThings(things);

++n;

}

Console.WriteLine("Called SetThings across AppDomain {0} times.", n);

}

Serializing across application domains results in terrible performance:

Over 1.2 million calls when not crossing an application domain, less than 6000 calls when crossing the application domain.

Even when we're passing a reference (the test case is changed to use the MutableListOfThings object):

static void Demo8()

{

DateTime now = DateTime.Now;

int n = 0;

IPlugIn plugin1 = new PlugIn1.PlugIn();

MutableListOfThings mutable = new MutableListOfThings();

mutable.Add(new Thing("A"));

mutable.Add(new Thing("B"));

mutable.Add(new Thing("C"));

while ((DateTime.Now - now).TotalMilliseconds < 1000)

{

plugin1.SetThings(mutable);

++n;

}

Console.WriteLine("Called SetThings {0} times.", n);

AppDomain appDomain1 = CreateAppDomain("PlugIn1");

plugin1 = InstantiatePlugin("PlugIn1", appDomain1);

now = DateTime.Now;

n = 0;

while ((DateTime.Now - now).TotalMilliseconds < 1000)

{

plugin1.SetThings(mutable);

++n;

}

Console.WriteLine("Called SetThings across AppDomain {0} times.", n);

}

we note that the performance is still terrible:

Working with application domains is not trivial -- classes must be serializable, there are design considerations and constraints as to whether to pass by value or by reference, and the performance is terrible. Is it worth making sure you have all your ducks in a row so that you can hot-swap an assembly? Well, "it depends" is the answer!

- 11th April, 2016: Initial version