Introduction

Attention: JEEP is not yet another single page application framework, neither is it another attempt to create a jQuery like library of utilities. This is a framework that is much deeper, and addresses the nature of the JavaScript language itself, and might be unlike what you might be used to. This article is best read with an open mind.

JEEP is an ambitious framework intended to impart features to JavaScript that enables robust software engineering by bringing object orientation to JavaScript beyond what is available in the language natively. Jeep makes it easy to create reusable, customizable and extensible components of complex structure and behavior compared what can be done with plain JavaScript code. It is a C++ inspired framework that tries to make JavaScript look, feel and behave like C++ for the most part, but fear not, it only imports the best features.

Jeep has a host of features and they all revolve around structure and semantics. Jeep is a rather large, complex and comprehensive framework, and what is shown here is the proverbial tip of the iceberg, but in the positive sense. You would have to read the 130+ page document at the github repository in which I discuss every aspect of the framework at length in order to fully appreciate Jeep. For simplicity, the features are reduced to these two lists.

Qualitative Features

- enforces syntax and semantic rules strictly and imparts robustness to code

- promotes writing intuitive, readable and easily extensible code

- allows code to be highly structured and organized

- improves productivity and performance

Technical Features

- offers a range of objects to help model data and behavior appropriately

- allows member with

public, protected and private access restriction - allows member variables and functions to be constant

- allows a series of validations on functions such as argument types, count, etc.

- allows single and multiple inheritance with

virtual and abstract functions - provides development mode and production modes (like debug and release build)

- and much much more

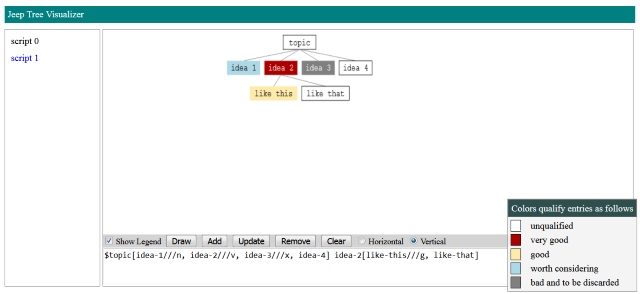

A small hierarchy visualization tool is created for the demonstration. The hierarchy is intended to represent a brainstorming session. The tool is actually a simpler variation of the one shown in the example chapter of the Jeep manual. That tool was created to help me visualize class hierarchies and reason about their correctness.

To showcase the advantages of using Jeep, the code is compared and contrasted with plain JavaScript code. I will briefly introduce the different aspects of Jeep that we encounter in the process.

The Application

The UI has five components – diagram, script box, script toolbar, script list and legend. The script list is your typical explorer UI. The buttons do as the names suggest; Draw only draws, Add draws and adds the script to the list, Update draws and updates the current script, Remove removes the current script. The Ctrl+Enter key combination is equivalent to clicking the Draw button.

The script is very simple with limited power due to this being a sample application. The general pattern is parent[child1, child2, ...], where each entry is a name printed in the box. The names must not contain spaces, instead use hyphens that will be converted to spaces.

The name itself follows this pattern <nudge><root><dup>name<args> and everything in angle brackets are optional.

nudge is one or more plus signs, intended to move a box downwards (or rightwards depending on the orientation) if the space cramps. Every plus sign moves the box a constant step.root is a single dollar character that indicates that the box will be a root box. There can be multiple roots.dup is a single dot that allows multiple boxes with the same name. Boxes and names have one to one correspondence. A name occurring multiple times refer to the same box, so this was needed for flexibility. However, you can’t refer to the duplicate names after their creation as each duplicate name generates a different box.args are a series of forward slash separated extra information called arguments. The first argument is always the background color, and the second is always the text color. The colors are RGB values given as 6 hexadecimal digits. The third is a single character, and can be one of the following and sets the box with the associated property.

- v = very good

- g = good

- n = worth considering

- x = bad and to be discarded

If a valid property is set, the application will override the colors set by other arguments. The arguments can be empty, but the order has to be maintained. So if you want to set only properties, you must have three slashes with the property appearing at the end.

Since a repeating name always refers to the first box that the name created, colors and properties set later will override the ones set earlier.

Note that a name which is not a root and doesn’t have a parent will not appear in the diagram, though it will be internally created.

You may play around with the script but remember that this is a sample only and has a limited set of features. The need for plus signs is one such – I didn’t want to implement an intricate alignment logic so the burden of alignment is on the user.

The Implementation

Note that Jeep is essentially JavaScript, so the implementation details are irrelevant since the same details can be used in plain JavaScript style coding. The reason Jeep exists is to provide organization and robustness to JavaScript code, so only those aspects will be demonstrated. To be clear, what is shown here is not how the tool implements its functionalities, but rather how the overall code looks at the architecture level.

The UI is made up of canvas, used for drawing, and various HTML elements.

Function Centric JavaScript Code

The simplest code would look like this:

function drawHierarchy(canvas, script, orientation){}

The biggest problem with this is that the function would have to encapsulate all the implementation details. All the helper functions it uses to do the alignment, etc. must be within the function in order to avoid accidental usage from outside. This obviously has performance overhead. If you take these functions outside to the global scope, you would risk not only accidental usage, but accidental overwriting. You would need to create a helper object with a random enough name and move the details inside it. This method is already quite a nightmare organization wise.

Further, functionality wise, this kind of code is not extensible. A bit of thought would show that the hierarchy can be turned into a general purpose component. The only thing that separates different hierarchies is the meaning of the arguments, except the coloring ones that are fixed at position one and two. The arguments amount to painting the boxes in different colors.

With this in mind, the function would need upgrading to something like this:

function drawHierarchy(canvas, script, orientation, colorMap){}

where the colorMap argument could be a key value pair of argument and the associated colors. This function would be called like this:

drawHierarchy(document.getElementById("diagram"), scriptBox.value,

getHierarchyOrientation(), {

v: {color: "#aa0000", txcolor: "white"},

x: {color: "gray", txcolor: "white"}

})

The function would work fine, as long you stick to only painting. What if you want some mouse interaction? Well, you could upgrade the function to this:

function drawHierarchy(canvas, script, orientation, colorMap, actionMap){}

where the actionMap argument could be a key value pair of mouse event names and the associated handlers. Now, anticipating such future expansions, you could change the function to look like this:

function drawHierarchy(canvas, script, orientation, options){}

where options argument is an object into which you move the color, action and other maps like this: {colorMap: {}, actionMap: {}}.

Though an acceptable way to do the task, this function suffers from an injection problem – you would have to do dependency injection all over the place in order for this to work as a general purpose component. Just imagine having to show a popup when double clicking on a box and also highlight all the related boxes. Well, it's not that bad because plain JavaScript code has been creating applications with more complex behaviors than this, but the point is that there is a better way to do this.

Object Centric JavaScript Code

The obvious way to create a reusable component is to make it a class. Please know that I haven’t ever used the new class syntax in JavaScript, so I won’t venture to use that now, here, and the old prototype style might be a bit jarring to most people, and I am rusty in that, so I won’t show that either. Basically, I won’t show any code in this section.

With JavaScript classes, it becomes trivially easy to create different kinds of hierarchies with different appearance and behavior, however this method suffers from three important problems due to using a flawed and imperfect object orientation mechanism.

Firstly, the implementation details are still open to accidental usage. You would have to either create a private object as mentioned before, or use naming conventions, say lowercases beginning names are private, and document them hoping that the programmer reads and abides by it.

Secondly, what happens if a derived class has members with names clashing with base names but represent different objects? This will fail silently, but not for long though, but the point is its flawed and imperfect.

Thirdly, and most importantly, what if you need to make the hierarchy serializable? It is most likely that there is a serializable class which must be extended to make the derived class serializable. However, such a thing cannot happen in this case since JavaScript doesn’t offer multiple inheritance, and, mixins being as bad as things can get, you would be forced to work with composition or dependency injection, which doesn’t lend itself to natural usage patterns or being useful. For instance, suppose the application had an array of serializable objects that are processed by calling the appropriate member functions. An instance of the serializable hierarchy can’t avail this benefit and must be processed separately.

Coding with JEEP

Code written with Jeep is superior to plain JavaScript code in all respects, and solves all the above mentioned problems and sticky situations. Jeep offers object orientation mechanism that is more comprehensive and robust than what JavaScript has natively.

The application components are modeled as Jeep classes. We need two classes, one for the hierarchy and one for the canvas. The canvas painting is itself quite general purpose and it makes sense to use a class that abstracts most of the gory details, such as context, instead of repeating them everywhere.

The Painter class that handles the painting on the canvas looks like this.

RegisterClassDef("Painter", {

CONSTRUCTOR: function(canvas){

this.canvasElement = canvas || document.createElement("canvas");

this.ctx = this.canvasElement.getContext('2d');

},

PUBLIC: {

Reset: function(){},

Scale: function(x, y){},

DrawLine: function(line){},

DrawRectangle: function(rect){},

DrawText: function(text){},

GetTextWidth: function(text){},

},

PRIVATE: {

ctx: null,

canvasElement__get: null,

saveProps: function(){},

restoreProps: function(){},

}

})

Notice how intuitive and readable the code is. I hope you have already figured out what things mean, but I will still explain briefly as it's my job as the writer.

A class, or any object Jeep offers, must be first defined before it can be instantiated. The definition generation is of two kinds – creating and registering. The first method returns an object that is local to the scope, while the latter makes the definition available globally to all application code. General purpose definitions obviously need to be registered. The RegisterClassDef function is actually a member of a couple of objects, and not a free function as it appears here, but for sake of brevity, that part is not discussed here.

The first argument is the name and the second is the declaration. The definition is generated based on the given declaration, and only if it complies with the syntax and semantics; otherwise Jeep aborts with a series of error messages detailing the invalidity of the declaration. All objects Jeep offers follow similar syntax but the declaration changes for obvious reasons.

The public members are accessible by all code and private only by own member functions. Attempt to access private members from any other code generates runtime error. The constructor is a special function called first upon instantiation; it can’t be invoked explicitly by any other means. By default, it is public.

The weird suffix _get is called directive, and both member variables and functions can have one or more of it. Directives are processed away and not retained as part of the name. A directive is effectively Jeep’s keyword that modifies behavior or affects code generation. Since Jeep is really JavaScript and not a separate programming language, it cannot invent syntax with spaces, so it improvises. This particular directive automatically generates a public function that returns the named variable. This spares you a lot of boilerplate code.

The arguments to the point, line and text functions are record instances. A record is an object intended to be pure data, and act as building block for the application, and don’t have functions such as constructor. The associated records are shown below. The rectangle and text records have some things in common, so they can extend from a common record.

let Item =CreateRecordDef("Item", {

x: 0,

y: 0,

})

RegisterRecordDef("Line", {

xa: 0,

ya: 0,

xb: 0,

yb: 0,

color: ""

})

RegisterRecordDef("Rectangle", {

EXTENDS: [Item],

width: 0,

height: 0,

fillColor: "",

lineColor: "",

})

RegisterRecordDef("Text", {

EXTENDS: [Item],

content: "",

font: "14pt Verdana",

color: "black",

align: "center",

})

With any object, the values given to variables in the declaration are the intended default values. The instance members will have these values unless a constructor modifies them, or the instantiation is done with different values. Instantiation happens via the New and InitNew functions that are properties of the definition object. The former instantiates with default values, and the latter with the values given as arguments. With the latter, the unspecified variables will take on default values.

let t = Text.New()

let tt = Text.InitNew({color: "red", align: "center"})

I hope you see how easy it is to create and use data with Jeep compared to plain JavaScript code.

The hierarchy is generated and painted by the Tree class defined as follows:

RegisterClassDef("Tree", {

CONSTRUCTOR: function(width, height){},

PUBLIC: {

Paint: function(painter, LayoutManagerDef){},

Reset: function(script, painter, LayoutManagerDef){},

PROTECTED: {

GetNodeColors__virtual: function(args){},

},

PRIVATE: {

root: null,

processName: function(n){},

}

})

There are three important things to notice about this class:

- The painting is done with the painter instance and not directly on the canvas. The caller of the function sets up and manages the instance.

- The colors are acquired via a

protected virtual function by providing it with the arguments. The significance of this will be known shortly. - The layouting is via the policy pattern instead of dependency injection pattern. The policy is implemented by a class shown below.

Protected members are accessible only to the class’ own members and its derived classes. Virtual functions are how polymorphism is achieved. If you needed a behavior on mouse click, you add an appropriate virtual function and invoke it at appropriate location in the base class. I hope you realize that extending behavior is quite simple, almost trivial in Jeep compared to plain JavaScript code. Virtual functions are best made protected since they are mostly going to be implementation details. You can make them private if you don’t want derived classes to invoke base class’s implementation.

The LayoutBase class establishes the policy and it looks like this:

RegisterClassDef("LayoutBase", {

PUBLIC: {

SetupPositions__abstract: function(nodeArr, width, height){},

},

PROTECTED: {},

})

An abstract function is very much like a virtual function except that its presence obligates the derived classes to implement it. Classes with unimplemented abstract functions cannot be instantiated; any attempt to do so will generate runtime error. The layout’s abstract function does the node arrangement agnostically, in that it doesn’t care about the contents or context of the node but simply sets the x and y coordinates of every entry in the given array. The nodes given here are actually different from the ones maintained internally by the tree, and the tree translates it back and forth. This is done because the layout is a third party code and the tree doesn’t trust such code but still has to deal with them.

The two layouts are implemented with these two classes:

RegisterClassDef("VertLayout", {

EXTENDS: [LayoutBase],

CONSTRUCTOR: function(){},

PUBLIC: {

SetupPositions__virtual: function(nodeArr, width, height){},

},

})

RegisterClassDef("HorzLayout", {

EXTENDS: [LayoutBase],

CONSTRUCTOR: function(){},

PUBLIC: {

SetupPositions__virtual: function(nodeArr, width, height){},

},

})

At this stage, we have all the components to build the application, except that the hierarchy will show white boxes with black text because the general purpose component doesn’t know about application specific argument meanings. So we have to extend the tree and implement the virtual function appropriately. The class looks like this:

let AppTree = CreateClassDef("AppTree", {

EXTENDS: [TinyTreeLib.GetObjectDef("Tree")],

PROTECTED: {

GetNodeColors__virtual: function(args){},

},

STATIC: {

GetLegend: function(){},

},

});

Jeep offers an object called library that, as the name indicates, helps in neatly organizing code such that accidental usages, name clashes, etc. won’t happen. It also provides a nice interface to declare, build, initiate and access. However, for the sake of brevity, I won’t discuss them here. All objects shown so far are members of multiple libraries. The TinyTreeLib is a variable the application created to store the retrieved library and not generated by Jeep automatically.

Static members are those that can be accessed without instantiating the class. They can also be private, but are public by default. The legend generation is not instance specific, so it was appropriate to make it static.

The legend is created using a structure, which is a light weight class provided by Jeep. Structures are intended to implement simple utilities unlike classes that are full fledged models of application requirements. Structures have declarations similar to records but behavior similar to classes. They also have restricted features, for instance, you can’t extend them.

The structure managing the legend looks like this. The constructor takes the title and the key value pair of color and their labels. The legend can be modified dynamically which helps in applications where users can define their own meanings and arguments.

RegisterStructDef("Legend", {

CONSTRUCTOR: function(msg, cmap){},

GetDOMElement: function(){},

Clear: function(){},

Append: function(cmap){},

})

The application script brings together all these components as shown in the snippet below:

canvas = document.createElement("canvas");

diagElem = document.getElementById("diagram");

diagElem.appendChild(canvas)

canvas.height = diagElem.offsetHeight;

canvas.width = diagElem.offsetWidth;

tree = AppTree.New(canvas.offsetWidth, canvas.offsetHeight)

Painter = TinyCanvasLib.GetObjectDef("Painter")

painter = Painter.New(canvas)

painter.Scale(canvas.width/canvas.width, canvas.width/canvas.height)

legend = AppTree.STATIC.GetLegend();

legend.style.position = "fixed";

legend.style.right = "5px";

legend.style.bottom = "5px";

legend.style.display = "none";

document.body.appendChild(legend);

function render(){

tree.Reset(scriptBox.value, painter, getSelectedLayout())

}

document.getElementById("draw-script").onclick = function(){

render();

}

Conclusion

The purpose of the document was to show how coding with Jeep is superior to using plain JavaScript code when dealing with applications of even small amount of complexity, both in structure and behavior.

The main takeaway from this document must be these.

- Jeep promotes writing intuitive, readable and easily extensible code.

- Jeep offers several objects to help organize code and model data and behavior.

- Jeep offers mechanisms to hide implementation details effectively.

- Jeep offers mechanisms to implement polymorphic behavior effectively.

What was shown here is only a glimpse of what Jeep has to offer. There is multiple inheritances, constant functions, automatic destruction mechanism and so much more intended to make JavaScript code robust and powerful. Visit the github repository to know more.

Jeep tries to offer all these features with minimum overhead, and sometimes none at all depending on many factors. I hope your interest has been piqued enough to make you read about Jeep and experiment with it.