Introduction

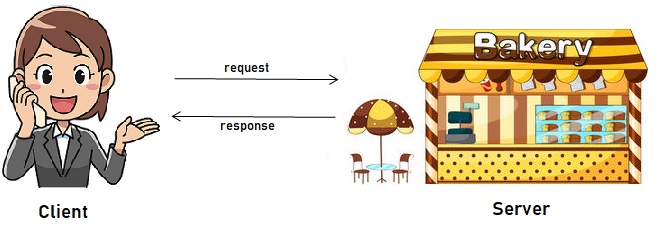

Socket programming is nothing of a new concept for programmers. Ever since the internet came into existence, it shifted the paradigm to internet-enabled applications. That’s where network programming models starts to appear. A socket is fundamentally the most basic technology of this network programming. Let alone the technology for the moment, in most cases, it’s literally just a client-server model working. Server is supposed to serve the information requested or the required services by the client. The following analogy will help you understand the model.

But how does that transfer of information take place? Well, that involves networking services from transport layer often referred to as TCP/IP (Transport Control Protocol/Internet Protocol). For example, when you open your browser and search for something, you’re merely requesting a server for some information over HTTP (not to forget HTTP is nothing but an application using TCP/IP service). But where are the sockets? Let me refer you back to the line where I said sockets are the “base” and so they provide the programming interface for these protocols to work on. Generally speaking, sockets are providing a way for two processes or programs to communicate over the network. Sockets provide sufficiency and transparency while causing almost no communication overhead.

Source

Why C++ though? As I mentioned earlier, sockets are merely providing an interface for network programming and have nothing to do with programming language used for implementation. C++ might be the best choice in this regard because of the speed and efficiency it brings to the table. Some might not agree with me at this statement because of implied complexity by the language including but not restricted to manual memory management, template syntax, library incompatibility, compiler, etc. But I think differently. C++ will let you dig deep and see the insights of what actually is going on at the lower level although good concept and knowledge in computer networks is not debatable. This article will help you in giving a soft start with socket programming in C++ using boost library. But before digging into the code, let’s clarify a few points a bit more.

What Socket Programming is All About?

Let’s talk about what a socket actually is and how it plays its role in the communication.

Socket is merely one endpoint of a two-way communication link. It represents a single connection between two entities that are trying to communicate over the network most of the time which are server and client. More than two entities can also be set to communicate but by using multiple sockets.

This socket-based communication is done over the network; one end of which could be your computer while other could be at the other end of the world (considering again the browsing example) or over the same machine (local host). Now the question arises how the server knows that a client is requesting for connection and also which service is being requested? This all is the game of IP address and port number. Every computer has a specific IP address which will be used to identify it. (If you’re accessing a website, then the name will eventually be translated into IP address.) Which service, is distinguished by port number.

Now to sum it all up when a client is requesting a server for services, it opens a socket and passes the request to the server by specifying its IP address and port number (to let server know which service is meant to be provided.) The server will accept the connection request and transfer the data or provide any other service requested. Once request is served, the connection will be closed. Observe the workflow in the following diagram.

Why Boost.Asio?

Writing networking code that is portable is easy to maintain has been an issue since long. C++ took a step to resolve this issue by introducing boost.asio. It is a cross-platform C++ library for network and low-level I/O programming that provides developers with a consistent asynchronous model using a modern C++ approach. Here’s a list of what it offers:

- Cross platform networking code (code would work on Windows, Linux, etc.)

- IPv4 and IPv6 support

- Asynchronous event support

- Timer support

- iostream compatibility

And much more. You can get the complete overview of the library here.

We are not going to dig deep into networking but rather will develop a simple client-server model and see how things work. So without any further delay, let’s get started.

Environment Setup

I’m currently in Linux (18.04 LTS) so would be covering environment setup for the same.

We just need the following to get started:

boost.asio- C++ compiler (preferably g++)

- Text-editor

The simplest way to get asio on linux is by executing the following command:

$ sudo apt-get install libboost-all-dev

If you’re using some other platform or the above doesn’t seem a good fit for you, follow the document here to get asio on your system.

The next step is to make sure you have C++ compiler on your compiler. I’m using g++. You can get the same with the following command in linux.

$ sudo apt-get install g++

Once you have the compiler, you’re good to follow along. I don’t have any text-editor preference. You can choose one of your choice.

Now that we have everything, we are in a position to start coding for our TCP server-client model.

TCP Server

As we mentioned earlier in the article, the server specifies an address for client at which it makes a request to server. Server listens for the new connection and responds accordingly. Now here are the steps for our server development.

Of course, we need to import our libraries before anything else. So here we go:

#include <iostream>

#include <boost/asio.hpp>

using namespace boost::asio;

using ip::tcp;

using std::string;

using std::cout;

using std::endl;

using namespace std is considered a bad practice for the reason that it imports all sorts of names globally and can cause ambiguities. As we just need three names that belong to std namespace, it's better to import them separately or else suit yourself.

We want our server to receive a message from client and then respond back. For that, we need two functions for read and write.

string read_(tcp::socket & socket) {

boost::asio::streambuf buf;

boost::asio::read_until( socket, buf, "\n" );

string data = boost::asio::buffer_cast<const char*>(buf.data());

return data;

}

void send_(tcp::socket & socket, const string& message) {

const string msg = message + "\n";

boost::asio::write( socket, boost::asio::buffer(message) );

}

Let’s break things down a little bit. Here, we are using tcp socket for communication. read_until and write functions from boost::asio has been used to perform the desired function. boost::asio::buffer creates a buffer of the data that is being communicated.

Now that we have our functions, let’s kick the server in.

int main() {

boost::asio::io_service io_service;

tcp::acceptor acceptor_(io_service, tcp::endpoint(tcp::v4(), 1234 ));

tcp::socket socket_(io_service);

acceptor_.accept(socket_);

string message = read_(socket_);

cout << message << endl;

send_(socket_, "Hello From Server!");

cout << "Servent sent Hello message to Client!" << endl;

return 0;

}

io_service object is needed whenever a program is using asio. tcp::acceptor is used to listen for connection requested by the client. We are passing two arguments to the function; one is the same io_service object we declared previously and next is the end point of connection being initialised to ipv4 and port 1234. Next server will create a socket and wait for connection from client. As soon as the connection is built, our read and write operations will be executed and connection will be closed.

TCP Client

We need the other end for our communication as well, i.e., a client that requests server. The basic structure is the same as we did for server.

#include <iostream>

#include <boost/asio.hpp>

using namespace boost::asio;

using ip::tcp;

using std::string;

using std::cout;

using std::endl;

Those are the same imports as we did for server. Nothing new.

int main() {

boost::asio::io_service io_service;

tcp::socket socket(io_service);

socket.connect( tcp::endpoint( boost::asio::ip::address::from_string("127.0.0.1"), 1234 ));

const string msg = "Hello from Client!\n";

boost::system::error_code error;

boost::asio::write( socket, boost::asio::buffer(msg), error );

if( !error ) {

cout << "Client sent hello message!" << endl;

}

else {

cout << "send failed: " << error.message() << endl;

}

boost::asio::streambuf receive_buffer;

boost::asio::read(socket, receive_buffer, boost::asio::transfer_all(), error);

if( error && error != boost::asio::error::eof ) {

cout << "receive failed: " << error.message() << endl;

}

else {

const char* data = boost::asio::buffer_cast<const char*>(receive_buffer.data());

cout << data << endl;

}

return 0;

}

We again started by creating the io_service object and creating the socket. We need to connect to server using localhost (IP 127.0.0.1) and specifying the same port as we did for server to establish the connection successfully. Once the connection is established, we’re sending a hello message to server using boost::asio::write. If the message is transferred, then server will send back the respond. For this purpose, we have boost::asio::read function to read back the response. Now let‘s run our program to see things in action.

Compile and run the server by executing the following command:

$ g++ server.cpp -o server –lboost_system

$ ./server

Move to the other terminal window to run client.

$ g++ client.cpp -o client –lboost_system

$ ./client

Observe the workflow from the above output. The client sent its request by saying hello to the server after which the server responded back with hello. Once the data transfer is complete, connection is closed.

TCP Asynchronous Server

The above programs explain our simple synchronous TCP server and client in which we did the operations in sequential order, i.e., reading from socket then write. Each operation is blocking which means read operation should finish first and then we can do the write operation. But what if there is more than one client trying to connect to server? In case we don’t want our main program to be interrupted while we're reading from or writing to a socket, a multi-threaded TCP client-server is required to handle the situation. The other option is having an asynchronous server. We can start the operation, but we don’t know when it will end, we don’t need to know pre-hand either because it is not blocking. The other operations can be performed side by side. Think of synchronous as walkie-talkie where one can speak at a time whereas asynchronous is more like regular cellphone. Now that we know the basics, let‘s dive in and try to create an asynchronous server.

#include <iostream>

#include <boost/asio.hpp>

#include <boost/bind.hpp>

#include <boost/enable_shared_from_this.hpp>

using namespace boost::asio;

using ip::tcp;

using std::cout;

using std::endl;

We have two new imports, bind and enable_shared_from_this. We’ll be using the former to bind any argument to a specific value and route input arguments into arbitrary positions. The latter is to get a valid shared_ptr instance.

Let’s define a class to handle the connection as follows:

class con_handler : public boost::enable_shared_from_this<con_handler>

{

private:

tcp::socket sock;

std::string message="Hello From Server!";

enum { max_length = 1024 };

char data[max_length];

public:

typedef boost::shared_ptr<con_handler> pointer;

con_handler(boost::asio::io_service& io_service): sock(io_service){}

static pointer create(boost::asio::io_service& io_service)

{

return pointer(new con_handler(io_service));

}

tcp::socket& socket()

{

return sock;

}

void start()

{

sock.async_read_some(

boost::asio::buffer(data, max_length),

boost::bind(&con_handler::handle_read,

shared_from_this(),

boost::asio::placeholders::error,

boost::asio::placeholders::bytes_transferred));

sock.async_write_some(

boost::asio::buffer(message, max_length),

boost::bind(&con_handler::handle_write,

shared_from_this(),

boost::asio::placeholders::error,

boost::asio::placeholders::bytes_transferred));

}

void handle_read(const boost::system::error_code& err, size_t bytes_transferred)

{

if (!err) {

cout << data << endl;

} else {

std::cerr << "error: " << err.message() << std::endl;

sock.close();

}

}

void handle_write(const boost::system::error_code& err, size_t bytes_transferred)

{

if (!err) {

cout << "Server sent Hello message!"<< endl;

} else {

std::cerr << "error: " << err.message() << endl;

sock.close();

}

}

};

The shared_ptr and enabled_shared_from_this is to keep our object alive for any operation that refers to it. Then we created the socket pretty much the same way as we did in case of synchronous server. Now is the time to specify the functions we want to perform using that socket. We are using async_read_some and async_write_some functions to achieve the same functionality as that of our previously developed server but now asynchronously. boost::bind is being used to bind and route the arguments to handle_read/write. handle_read/write will now be responsible for any further action. If you look into the handle_read/write definition, it has the same arguments as the last two of boot::bind and is performing some action in case the data is successfully transferred between client and server or not.

class Server

{

private:

tcp::acceptor acceptor_;

void start_accept()

{

con_handler::pointer connection = con_handler::create(acceptor_.get_io_service());

acceptor_.async_accept(connection->socket(),

boost::bind(&Server::handle_accept, this, connection,

boost::asio::placeholders::error));

}

public:

Server(boost::asio::io_service& io_service): acceptor_(io_service, tcp::endpoint(tcp::v4(), 1234))

{

start_accept();

}

void handle_accept(con_handler::pointer connection, const boost::system::error_code& err)

{

if (!err) {

connection->start();

}

start_accept();

}

};

Our server class will create a socket and will start the accept operation to wait for connection asynchronously. We also defined a constructor for our server to start listening for connection on the specified port. If no error occurs, connection with the client will be established. Here’s our main function.

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

try

{

boost::asio::io_service io_service;

Server server(io_service);

io_service.run();

}

catch(std::exception& e)

{

std::cerr << e.what() << endl;

}

return 0;

}

Again, we need our io_service object along with an instance of Server class. run() function will block until all the work is done, until io_service is stopped.

It’s time to let our monster out. Compile and run the above code with:

$ g++ async_server.cpp -o async_server –lboost_system

$ ./async_server

Run your client again.

$ ./client

Note that the client closed the connection after exchanging the data but server is still up and running. New connections can be made to the server or else it will continue to run until explicitly asked to stop. If we want it to stop, then we can do the following:

boost::optional<boost::asio::io_service::work> work = boost::in_place(boost::ref(io_service));

work = boost::none;

This will tell run() that all work is done and not to block anymore.

End Words

This article is not meant to show you the best practices or making you a pro in network programming rather focused to give you an easy start with socket programming in boost.asio. It is a pretty handy library so if you’re interested in some high-end network programming, I would encourage you to take a deep dive and play around it more. Also, the source code of both server and client is attached. Feel free to make some changes and let me know if you have some good ideas.