This article explains Test Driven Development with a detailed sample showing how to create, refactor and build tests for a new feature and also how to polish and find bugs in the original implementation using the tests. I also talk about advantages and shortcomings of the unit tests and the fact that every project should decide for itself how many unit tests to write and how often to run them.

Introduction

What is Test Driven Development

Test Driven Development or (TDD for short) is the software development process that emphasizes refactoring the code and creating unit tests as part of the main software development cycle.

In its purest form, TDD encourages creating a test first and then creating implementations for the tested functionality.

It is my belief, however, that the software development should be driven by the functionality requirements, not the tests, so in this article, I demonstrate a modified (moderated) TDD approach which emphasizes refactoring and unit test creation as the integral part of the main coding cycle.

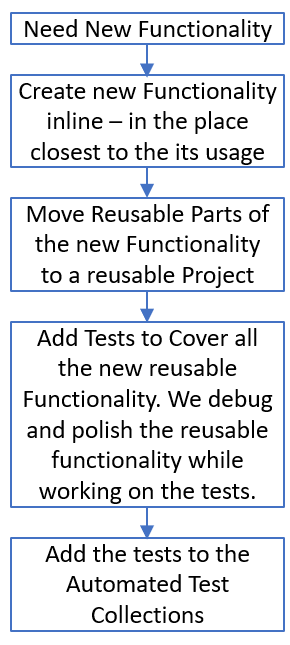

Here is a diagram detailing the TDD development cycle:

Do not worry if you are a bit confused - we are going to go over this development cycle in detail when describing our sample.

Note that the first 3 steps of the TDD Cycle presented above (which include refactoring) can and should be used continuously for any development, even when the tests are skipped:

This cycle can be called Coding with Refactoring.

This cycle will also be part of the Prototype Driven Development described in a future article.

TDD Advantages

- Developers are encouraged to factor out reusable functionality into reusable methods and classes.

- Unit tests are created together with the functionality (and not only when the developers have free time).

TDD Shortcomings

Sometimes too many tests are created even for trivial code, resulting in too much time spent on test creation and too much computer resources spent on running those tests making the builds slow.

Slowness of the builds might also significantly slow down the development further.

I saw whole projects ground to almost a halt because of the super slow builds.

Because of this, the decision of what functionality needs to be tested and what not and what tests should run and how often, should be taken by an experienced project architect and adjusted during the course of the project development as needed.

Different projects, might need different TDD guidelines depending on their size, significance, funding, deadlines, number and experience of their developers and QA resources.

Sample Code

The resulting sample code is located under TDD Cycle Sample Code.

Note, that since the purpose of this article is to present the process, it is imperative that you go over the tutorial starting with the empty projects and going through every step that would eventually result in the code of the sample.

I used Visual Studio 2022 and .NET 6 for the sample, but with small modifications (primarily related to the Program.Main(...) method) one can also use older versions of .NET and Visual Studio.

I used a popular (perhaps the most popular) XUnit framework to create and run the unit tests.

TDD Video

There is also a TDD video available at TDD Development Cycle Video going over the same material.

For best results, I recommend reading this article, going over the demo and watching the video.

TDD Development Cycle Demo

Start With Almost Empty Solution

Your initial solution should contain only three projects:

- Main project

MainApp - Reusable project

NP.Utilities (under Core folder) - Unit Test project

NP.Utilities.Test (under Tests folder)

MainApp's Program.cs file should be completely empty (remember it is .NET 6).

File StringUtils.cs of NP.Utilities project can contain an empty public static class:

public static class StringUtils { }

Both the main and test projects should reference NP.Utilities reusable project.

The test project NP.Utility.Test should also refer to XUnit and two other NuGet packages:

The two extra nuget packages, "Microsoft.NET.Test.SDK" and "xunit.runner.visualstudio" are required in order to be able to debug XUnit tests within the Visual Studio.

The easiest way to obtain the initial (almost empty) solution, is by downloading or git-cloning the TDD Cycle Sample Code, running the src/MainApp/MainApp.sln solution, removing all code from MainApp/Program.cs and NP.Utilities/StringUtils.cs files and removing the file NP.Utility.Tests/Test_StringUtils.cs.

You can also try creating such solution yourself (do not forget to provide the project and nuget package dependencies).

Requirement for New Functionality

Assume that you are creating new functionality within Program.cs file of the main solution.

Assume also, you need to create new functionality to split the string "Hello World!" into two strings - one preceding the first instance of "ll" characters and one that follows the same characters - of course, such two resulting strings will be "He" and "o World!".

Start by defining the initial string and the separator string within Program.cs file:

string str = "Hello World!";

string separator = "ll";

Also note - we mentioned the start and end result parts in the line comment.

Important Note: For the purpose of this demo, we assume that the method string.Split(...) does not exist, even though we use some simpler methods from string type (string.Substring(...) and string.IndexOf(...)). Essentially, we re-implement a special simpler version of Split(...) that only splits around the first instance of the separator and returns the result as a tuple, not array.

Create New Functionality Inline - Closest to Where it is Used

We start by creating the new functionality in the most simple, straightforward way, non-reusable way next to where it is used - within the same Program.cs file:

string str = "Hello World!";

string separator = "ll";

int separatorIdx = str.IndexOf(separator);

string startStrPart = str.Substring(0, separatorIdx);

int endPartBeginIdx = separatorIdx + separator.Length;

string endStrPart = str.Substring(endPartBeginIdx);

Console.WriteLine($"startStrPart = '{startStrPart}'");

Console.WriteLine($"endStrPart = '{endStrPart}'");

The code is simple and is explained in the comments.

Of course, the code runs fine and prints:

startStrPart = 'He'

endStrPart = 'o World!'

as it should.

Wrap the Functionality in a Method Within the Same File

At the next stage, let is slightly generalize the functionality, by creating a method BreakStringIntoTwoParts(...) taking the main string and the separator and returning a tuple containing the first and second parts of the result. Then, we use this method to get the start and end parts of the result.

At this stage, for the sake of simplicity, place the method into the same file Program.cs:

(string startStrPart, string endStrPart) BreakStringIntoTwoParts(string str, string separator)

{

int separatorIdx = str.IndexOf(separator);

string startStrPart = str.Substring(0, separatorIdx);

int endPartBeginIdx = separatorIdx + separator.Length;

string endStrPart = str.Substring(endPartBeginIdx);

return (startStrPart, endStrPart);

}

string str = "Hello World!";

string separator = "ll";

(string startStrPart, string endStrPart) = BreakStringIntoTwoParts(str, separator);

Console.WriteLine($"startStrPart = '{startStrPart}'");

Console.WriteLine($"endStrPart = '{endStrPart}'");

Run the method and, of course, you'll get the same correct string split.

Experienced .NET developers, might notice that the method code is buggy - at this point, we do not care about it. We shall deal with the bugs later.

Move the Created Method into Generic Project NP.Utilities

Now, we move our method over to StringUtils.cs file located under the reusable NP.Utilities project and modify it to become a static extension method for convenience:

namespace NP.Utilities

{

public static class StringUtils

{

public static (string startStrPart, string endStrPart)

BreakStringIntoTwoParts(this string str, string separator)

{

int separatorIdx = str.IndexOf(separator);

string startStrPart = str.Substring(0, separatorIdx);

int endPartBeginIdx = separatorIdx + separator.Length;

string endStrPart = str.Substring(endPartBeginIdx);

return (startStrPart, endStrPart);

}

}

}

We also add using NP.Utilities; line at the top of our Program.cs file and modify the call to the method to:

(string startStrPart, string endStrPart) = str.BreakStringIntoTwoParts(separator);

- since the method now is an extension method.

Re-run the application - you should obtain exactly the same result.

Create a Single Unit Test to Test the Method with the Same Arguments

Now, finally we are going to create a unit test to test the extension method (aren't you excited).

Under NP.Utility.Tests project, create a new class Test_StringUtils. Make the class public and static (no state is necessary for testing the string methods).

Add the following using statements at the top:

using NP.Utilities;

using Xunit;

to refer to our reusable NP.Utilities project and to XUnit.

Add a public static method BreakStringIntoTwoParts_Test() for testing our BreakStringIntoTwoParts(...) method and mark it with [Fact] XUnit attribute:

public static class Test_StringUtils

{

[Fact]

public static void BreakStringIntoTwoParts_Test()

{

string str = "Hello World!";

string separator = "ll";

string expectedStartStrPart = "He";

string expectedEndStrPart = "o World!";

(string startStrPart, string endStrPart) = str.BreakStringIntoTwoParts(separator);

Assert.Equal(expectedStartStrPart, startStrPart);

Assert.Equal(expectedEndStrPart, endStrPart);

}

The last two Assert.Equal(...) methods of XUnit framework are called in order to error out in case any of the expected values does not match the corresponding obtained value.

You can remove now, the Console.WriteLine(...) calls from the main Program.cs file. Anyways, in a couple of weeks, no one will be able to remember what those prints were supposed to do.

In order to run the tests, open the test explorer by going to "TEST" menu of the Visual Studio and choosing "Test Explorer":

Test explorer window is going to pop up:

Click on Run icon (second from the left) to refresh and run all the tests

After that, expand to our BreakStringIntoTwoParts_Test - it should have a green icon next to it indicating that the test ran successfully:

Now, let us create a test failure by modifying the first expected value to something that is not correct, e.g., to "He1" (instead of "He"):

string expectedStartStrPart = "He1";

Rerun the test - it will have a red icon next to it and the window on the right will give the cause of an Assert method failure:

Now change the expectedStartStrPart back to the correct value "He" and rerun the test to set it back to green.

Debugging the Test

Now I am going to show how to debug the created test.

Place a breakpoint within the test method, e.g., next to the call to BreakStringIntoTwoParts(...) method:

Then, right click on the test within the test explorer and choose "Debug" instead of "Run":

You'll stop at the break point within the Visual Studio debugger. Then, you'll be able to step into a method or over a method and investigate or change the variable values the same way as you do for debugging of the main application.

Generalizing Our Test to Run with Different Parameters using InlineData Attribute

As you might have noticed, our test covers only a very specific case with main string set to "Hello World!", separator "ll" and expected returned values "He" and "o World!" correspondingly.

Of course, in order to be sure that our method BreakStringIntoTwoParts(...) does not have any bugs, we need to test many more cases.

XUnit allows us to generalize the test method in such a way that it gives us the ability to test many different test cases.

In order to achieve that, first change [Fact] attribute of our test method to [Theory].

[Theory]

public static void BreakStringIntoTwoParts_Test(...)

{

...

}

Then, change the hardcoded parameters defined within our test:

string str = "Hello World!";

string separator = "ll";

string expectedStartStrPart = "He";

string expectedEndStrPart = "o World!";

into method arguments:

[Theory]

public static void BreakStringIntoTwoParts_Test

(

string str,

string? separator,

string? expectedStartStrPart,

string? expectedEndStrPart

)

{

...

}

As you see, we allow separator and two expected value to be passed as nulls.

Finally, after [Theory] attribute and on top of the test method, add [InlineData(...)] attribute passing to it the 4 input parameter values as we want to pass them to the test method.

For the first [InlineData(...)] attribute, we shall pass the same parameters that were hardcoded within the method itself before:

[Theory]

[InlineData("Hello World!", "ll", "He", "o World!")]

public static void BreakStringIntoTwoParts_Test

(

string str,

string? separator,

string? expectedStartStrPart,

string? expectedEndStrPart

)

{

(string startStrPart, string endStrPart) = str.BreakStringIntoTwoParts(separator);

Assert.Equal(expectedStartStrPart, startStrPart);

Assert.Equal(expectedEndStrPart, endStrPart);

}

Refresh the tests by running all of them in order to get the test with the new signature. The test will run successfully and the pane on the right will show parameters passed to it:

Creating More Tests using InlineData Attribute

Case when the Separator matches the Beginning of the String

Assume we want to test the case when the separator matches the beginning of the string. Let us add another InlineData(...) attribute passing the same main string, the separator "Hel" and the first and last expected result parts should, of course be an empty string and "lo World!" correspondingly:

[Theory]

[InlineData("Hello World!", "ll", "He", "o World!")]

[InlineData("Hello World!", "Hel", "", "lo World!")]

public static void BreakStringIntoTwoParts_Test

(

string str,

string? separator,

string? expectedStartStrPart,

string? expectedEndStrPart

)

{

...

}

Note that our new test corresponds to the second inline data parameters:

[InlineData("Hello World!", "Hel", "", "lo World!")]

Rerun all tests within the Test Explorer to refresh them. The new test will show up as not run (blue icon) within the Test Explorer:

Click on the test corresponding to the new InlineData and run it - it should succeed and turn green.

Notice that there is a disturbing fact that the order of the InlineData attributes and the order of the corresponding tests within the Test Explorer do not match.

The tests within the Test Explorer are sorted alphanumerically according to their parameter values - since the separator parameter of the second InlineData ("Hel") alphanumerically precedes the separator "ll" of the first InlineData, the corresponding tests appear in reverse order.

In order to fix this problem, I introduce another (unused) double input argument testOrder as the first parameter to our BreakStringIntoTwoParts_Test(...) method. Then, within the InlineData(...) attributes, I assign the parameter according to the order of the InlineData:

[Theory]

[InlineData(1, "Hello World!", "ll", "He", "o World!")]

[InlineData(2, "Hello World!", "Hel", "", "lo World!")]

public static void BreakStringIntoTwoParts_Test

(

double testOrder,

string str,

string? separator,

string? expectedStartStrPart,

string? expectedEndStrPart

)

{

}

This makes the tests appear (after a refresh) within the Test Explorer according to the order of the first argument testOrder which is the same as the order of the InlineData:

Case when the Separator matches the End of the String

Next, we can add an inline data to test that our method also works when the separator matches the end of the string, e.g., if separator is "d!", we expect the first part of the result tuple to be "Hello Worl" and the second part - empty string.

We add the attribute line:

[InlineData(3, "Hello World!", "d!", "Hello Worl", "")]

then, refresh and run the corresponding test and see that the test succeeds.

Case when the Separator is null

Now let us add InlineData with null separator. The first part of the result should be the whole string and the second - empty:

[InlineData(4, "Hello World!", null, "Hello World!", "")]

Refresh the tests and run the test corresponding to the new InlineData - it will show red, meaning that it detected a bug. You'll be able to see the stack of the exception on the right:

The stack trace shows that the exception is thrown by the following line of BreakStringIntoTwoParts(...) method implementation:

int separatorIdx = str.IndexOf(separator);

string.IndexOf(...) method does not like a null argument, so the case when separator is null should be made a special case with special treatment.

Note that even if the stack trace does not give enough information, you can always investigate the variable values at the point of failure via the debugger.

With an eye to the next test case - when the separator is neither null, nor part of the string - we shall initialize both the separatorIdx and the endPartBeginIdx to be the full string size and then only if the separator is not null - we shall assign separatorIdx to be str.IndexOf(separator) and endPartBeginIdx to be separatorIdx + separator.Length:

public static (string startStrPart, string endStrPart)

BreakStringIntoTwoParts(this string str, string separator)

{

int separatorIdx = str.Length;

int endPartBeginIdx = str.Length;

if (separator != null)

{

separatorIdx = str.IndexOf(separator);

endPartBeginIdx = separatorIdx + separator.Length;

}

string startStrPart = str.Substring(0, separatorIdx);

string endStrPart = str.Substring(endPartBeginIdx);

return (startStrPart, endStrPart);

}

Rerun the last test - it should run successfully and turn green. Rerun all the tests since we modified the tested method - they should all be green now.

Case when the Separator does not Exist within the String

Next test case is when the separator is not null, but does not exist within the string, e.g., let us choose separator = "1234". The expected result parts should be full string and empty string correspondingly:

[InlineData(5, "Hello World!", "1234", "Hello World!", "")]

Refresh the tests and run the test corresponding to the new InlineData. The test is going to fail:

pointing to the following line as the point at which exception is thrown:

string startStrPart = str.Substring(0, separatorIdx);

You can also debug to see the cause of the problem - which is that the separator is not null, and because of that, the separatorIdx is assigned to str.IndexOf(separator) which returns -1 since the separator is not found within the string. This causes the substring length passed to str.Substring(...) method to be negative which results in an ArgumentOutOfRangeException thrown.

In order to fix the problem, we should assign separatorIdx and endPartBeginIdx only if the separator exists in the string, i.e., when str.IndexOf(separarot) is not -1, otherwise leaving both indexes initialized to return full string/empty string as a result. Here is the code:

public static (string startStrPart, string endStrPart)

BreakStringIntoTwoParts(this string str, string separator)

{

int separatorIdx = str.Length;

int endPartBeginIdx = str.Length;

if (separator != null)

{

int realSeparatorIdx = str.IndexOf(separator);

if (realSeparatorIdx != -1)

{

separatorIdx = str.IndexOf(separator);

endPartBeginIdx = separatorIdx + separator.Length;

}

}

string startStrPart = str.Substring(0, separatorIdx);

string endStrPart = str.Substring(endPartBeginIdx);

return (startStrPart, endStrPart);

}

Rerun all the tests (since we change the tested method). All the tests should now succeed.

Case when the Separator is Repeated Several Times within the String

Finally, we want to set the separator to some sub-string that is found multiple times within the string. The correct processing returns the two parts according to the first instance of the separator within the string.

Set separator to "l" (character that repeats 3 times within "Hello World!" string). The correct result parts should be "He"/"lo World!":

[InlineData(6, "Hello World!", "l", "He", "lo World!")]

The new test should succeed right away.

The final test should look like that:

public static class Test_StringUtils

{

[Theory]

[InlineData(1, "Hello World!", "ll", "He", "o World!")]

[InlineData(2, "Hello World!", "Hel", "", "lo World!")]

[InlineData(3, "Hello World!", "d!", "Hello Worl", "")]

[InlineData(4, "Hello World!", null, "Hello World!", "")]

[InlineData(5, "Hello World!", "1234", "Hello World!", "")]

[InlineData(6, "Hello World!", "l", "He", "lo World!")]

public static void BreakStringIntoTwoParts_Test

(

double testOrder,

string str,

string? separator,

string? expectedStartStrPart,

string? expectedEndStrPart

)

{

(string startStrPart, string endStrPart) = str.BreakStringIntoTwoParts(separator);

Assert.Equal(expectedStartStrPart, startStrPart);

Assert.Equal(expectedEndStrPart, endStrPart);

}

}

Conclusion

We presented a full example of a Test Driven Development cycle only omitting the last step of adding the created test to Automation tests.

We showed how to start with a new feature, factor it out as a common method, then how to create multiple unit tests for the method and polish the method when finding bugs via those unit tests.

The great advantage of the unit tests is that they allow to test and debug any basic feature without a need to create a special console application for it - each unit test is essentially a laboratory for testing and debugging a certain application feature.

TDD also provides advantages of looking at the coding from the usage point of view, encouraging the refactoring and providing automation tests continuously during the development.

A great possible disadvantage is slowing down the development and builds.

Because of that, every architect and team should themselves decide how many unit tests they are going to create and how often they'll be running them. Such decision should optimize architecture and code quality, reliability and coding speed and should be a function of many variables including the developers' and QA personnel experience and quantity, project funding, deadlines and other parameters. Also, the optimal values might change throughout the duration of the project.

History

- 16th January, 2022: Initial version