Contents

*** NOTE *** This project has been migrated to GitHub: https://github.com/perspectivism/injecting-net-assemblies

.NET is a powerful language for developing software quickly and reliably. However, there are certain tasks for which .NET is unfit. This paper highlights one particular case, DLL injection. A .NET DLL (aka managed DLL) cannot be injected inside a remote process in which the .NET runtime has not been loaded. Furthermore, even if the .NET runtime is loaded in a process one would like to inject, how can methods within the .NET DLL be invoked? What about architecture? Does a 64 bit process require different attention than a 32 bit process? The goal of this paper is to show how to perform all of these tasks using documented APIs. Together, we will:

- Start the .NET CLR (common language runtime) in an arbitrary process regardless of bitness.

- Load a custom .NET assembly in an arbitrary process.

- Execute managed code in the context of an arbitrary process.

Several things need to happen in order for us to achieve our goal. To make the problem more manageable, it will be broken down into several pieces and then reassembled at the end. The steps to solving this puzzle are:

- Load The CLR (Fundamentals) - Covers how to start the .NET Framework inside of an unmanaged process

- Load The CLR (Advanced) - Covers how to load a custom .NET assembly and invoke managed methods from unmanaged code

- DLL Injection (Fundamentals) - Covers how to execute unmanaged code in a remote process

- DLL Injection (Advanced) - Covers how to execute arbitrary exported functions in a remote process

- Putting It All Together - A solution presents itself; putting it all together

Note: The author uses the standard convention of function to refer to C++ functions, and method to refer to C# functions. The term "remote" process refers to any process other than the current process.

Writing an unmanaged application that can load both the .NET runtime and an arbitrary assembly into itself is the first step towards achieving our goal.

The following sample program illustrates how a C++ application can load the .NET runtime into itself:

#include <metahost.h>

#pragma comment(lib, "mscoree.lib")

#import "mscorlib.tlb" raw_interfaces_only \

high_property_prefixes("_get","_put","_putref") \

rename("ReportEvent", "InteropServices_ReportEvent")

int wmain(int argc, wchar_t* argv[])

{

char c;

wprintf(L"Press enter to load the .net runtime...");

while (getchar() != '\n');

HRESULT hr;

ICLRMetaHost *pMetaHost = NULL;

ICLRRuntimeInfo *pRuntimeInfo = NULL;

ICLRRuntimeHost *pClrRuntimeHost = NULL;

hr = CLRCreateInstance(CLSID_CLRMetaHost, IID_PPV_ARGS(&pMetaHost));

hr = pMetaHost->GetRuntime(L"v4.0.30319", IID_PPV_ARGS(&pRuntimeInfo));

hr = pRuntimeInfo->GetInterface(CLSID_CLRRuntimeHost,

IID_PPV_ARGS(&pClrRuntimeHost));

hr = pClrRuntimeHost->Start();

wprintf(L".Net runtime is loaded. Press any key to exit...");

while (getchar() != '\n');

return 0;

}

In the above code, the calls of interest are:

CLRCreateInstance | Given CLSID_CLRMetaHost, gets a pointer to an instance of ICLRMetaHost |

ICLRMetaHost::GetRuntime | Get a pointer of type ICLRRuntimeInfo pointing to a specific .NET runtime |

ICLRRuntimeInfo::GetInterface | Load the CLR into the current process and get a ICLRRuntimeHost pointer |

ICLRRuntimeHost::Start | Explicitly start the CLR, implicitly called when managed code is first loaded |

At the time of this writing, the valid version values for ICLRMetaHost::GetRuntime are NULL, "v1.0.3705", "v1.1.4322", "v2.0.50727", and "v4.0.30319" where NULL loads the latest version of the runtime. The desired runtime should be installed on the system, and the version values above should be present in either %WinDir%\Microsoft.NET\Framework or %WinDir%\Microsoft.NET\Framework64.

Compiling and running the code above produces the following output as seen from the console and Process Hacker:

Once pressing enter, it can be observed, via Process Hacker, that the .NET runtime has been loaded. Notice the additional tabs referencing .NET on the properties pane:

The above sample code is not included in the source download. However, it is recommended as an exercise for the reader to build and run the sample.

With the first piece of the puzzle in place, the next step is to load an arbitrary .NET assembly into a process and invoke methods inside that .NET assembly.

To continue building off the above example, the CLR has just been loaded into the process. This was achieved by obtaining a pointer to the CLR interface; this pointer is stored in the variable pClrRuntimeHost. Using pClrRuntimeHost, a call was made to ICLRRuntimeHost::Start to initialize the CLR into the process.

Now that the CLR has been initialized, pClrRuntimeHost can make a call to ICLRRuntimeHost::ExecuteInDefaultAppDomain to load and invoke methods in an arbitrary .NET assembly. The function has the following signature:

HRESULT ExecuteInDefaultAppDomain (

[in] LPCWSTR pwzAssemblyPath,

[in] LPCWSTR pwzTypeName,

[in] LPCWSTR pwzMethodName,

[in] LPCWSTR pwzArgument,

[out] DWORD *pReturnValue

);

A brief description of each parameter:

pwzAssemblyPath | The full path to the .NET assembly; this can be either an EXE or a DLL file |

pwzTypeName | The fully qualified typename of the method to invoke |

pwzMethodName | The name of the method to invoke |

pwzArgument | An optional argument to pass into the method |

pReturnValue | The return value of the method |

Not every method inside a .NET assembly can be invoked via ICLRRuntimeHost::ExecuteInDefaultAppDomain. Valid .NET methods must have the following signature:

static int pwzMethodName (String pwzArgument);

As a side note, access modifiers such as public, protected, private, and internal do not affect the visibility of the method; therefore, they have been excluded from the signature.

The following .NET application will be used in all the examples that follow as the managed .NET assembly to be injected inside processes:

using System;

using System.Windows.Forms;

namespace InjectExample

{

public class Program

{

static int EntryPoint(String pwzArgument)

{

System.Media.SystemSounds.Beep.Play();

MessageBox.Show(

"I am a managed app.\n\n" +

"I am running inside: [" +

System.Diagnostics.Process.GetCurrentProcess().ProcessName +

"]\n\n" + (String.IsNullOrEmpty(pwzArgument) ?

"I was not given an argument" :

"I was given this argument: [" + pwzArgument + "]"));

return 0;

}

static void Main(string[] args)

{

EntryPoint("hello world");

}

}

}

The example application above was written in such a way that it can be called via ICLRRuntimeHost::ExecuteInDefaultAppDomain or run standalone; with either approach producing similar behavior. The ultimate goal is that when injected into an unmanaged remote process, the application above will execute in the context of that process, and display a message box showing the remote process name.

Building on top of the sample code from the Fundamentals section, the following C++ program will load the above .NET assembly and execute the EntryPoint method:

#include <metahost.h>

#pragma comment(lib, "mscoree.lib")

#import "mscorlib.tlb" raw_interfaces_only \

high_property_prefixes("_get","_put","_putref") \

rename("ReportEvent", "InteropServices_ReportEvent")

int wmain(int argc, wchar_t* argv[])

{

HRESULT hr;

ICLRMetaHost *pMetaHost = NULL;

ICLRRuntimeInfo *pRuntimeInfo = NULL;

ICLRRuntimeHost *pClrRuntimeHost = NULL;

hr = CLRCreateInstance(CLSID_CLRMetaHost, IID_PPV_ARGS(&pMetaHost));

hr = pMetaHost->GetRuntime(L"v4.0.30319", IID_PPV_ARGS(&pRuntimeInfo));

hr = pRuntimeInfo->GetInterface(CLSID_CLRRuntimeHost,

IID_PPV_ARGS(&pClrRuntimeHost));

hr = pClrRuntimeHost->Start();

DWORD pReturnValue;

hr = pClrRuntimeHost->ExecuteInDefaultAppDomain(

L"T:\\FrameworkInjection\\_build\\debug\\anycpu\\InjectExample.exe",

L"InjectExample.Program",

L"EntryPoint",

L"hello .net runtime",

&pReturnValue);

pMetaHost->Release();

pRuntimeInfo->Release();

pClrRuntimeHost->Release();

return 0;

}

The following screenshot shows the output of the application:

So far, two pieces of the puzzle are in place. It is now understood how to load the CLR and execute arbitrary methods from within unmanaged code. But how can this be done in arbitrary processes?

DLL injection is a strategy used to execute code inside a remote process by loading a DLL in the remote process. Many DLL injection tactics focus on code executing inside of DllMain. Unfortunately, attempting to start the CLR from within DllMain will cause the Windows loader to deadlock. This can be independently verified by writing a sample DLL that attempts to start the CLR from within DllMain. Verification is left as an excercise for the reader. For more information regarding .NET initialization, the Windows loader, and loader lock; please refer to the following MSDN articles:

Inevitably, the result is that the CLR cannot be started while the Windows loader is initializing another module. Each lock is process specific and managed by Windows. Remember, any module that attempts to acquire more than one lock on the loader when a lock has already been acquired will deadlock.

The issue regarding the Windows loader seems sizable; and whenever a problem seems large, it helps to break it down into more manageable pieces. Developing a strategy to inject a barebones DLL inside of a remote process is a good start. Take the following sample code:

#define WIN32_LEAN_AND_MEAN

#include <windows.h>

BOOL APIENTRY DllMain(HMODULE hModule, DWORD ul_reason_for_call, LPVOID lpReserved)

{

switch (ul_reason_for_call)

{

case DLL_PROCESS_ATTACH:

case DLL_THREAD_ATTACH:

case DLL_THREAD_DETACH:

case DLL_PROCESS_DETACH:

break;

}

return TRUE;

}

The above code implements a simple DLL. To inject this DLL in a remote process, the following Windows APIs are needed:

OpenProcess | Acquire a handle to a process |

GetModuleHandle | Acquire a handle to the given module |

LoadLibrary | Load a library in the address space of the calling process |

GetProcAddress | Get the VA (virtual address) of an exported function from a library |

VirtualAllocEx | Allocate space in a given process |

WriteProcessMemory | Write bytes into a given process at a given address |

CreateRemoteThread | Spawn a thread in a remote process |

Moving on, the purpose of the function below is to execute an exported function of a DLL that has been loaded inside a remote process:

DWORD_PTR Inject(const HANDLE hProcess, const LPVOID function,

const wstring& argument)

{

LPVOID baseAddress = VirtualAllocEx(hProcess, NULL, GetStringAllocSize(argument),

MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE, PAGE_READWRITE);

BOOL isSucceeded = WriteProcessMemory(hProcess, baseAddress, argument.c_str(),

GetStringAllocSize(argument), NULL);

HANDLE hThread = CreateRemoteThread(hProcess, NULL, 0,

(LPTHREAD_START_ROUTINE)function, baseAddress, NULL, 0);

WaitForSingleObject(hThread, INFINITE);

VirtualFreeEx(hProcess, baseAddress, 0, MEM_RELEASE);

DWORD exitCode = 0;

GetExitCodeThread(hThread, &exitCode);

CloseHandle(hThread);

return exitCode;

}

Remember that the goal in this section is to load a library in a remote process. The next question is how can the above function be used to inject a DLL in a remote process? The answer lies in the assumption that kernel32.dll is mapped inside the address space of every process. LoadLibrary is an exported function of kernel32.dll and it has a function signature that matches LPTHREAD_START_ROUTINE, so it can be passed as the start routine to CreateRemoteThread. Recall that the purpose of LoadLibrary is to load a library in the address space of the calling process, and the purpose of CreateRemoteThread is to spawn a thread in a remote process. The following snippet illustrates how to load our test DLL inside of a process with ID 3344:

HANDLE hProcess = OpenProcess(PROCESS_ALL_ACCESS, FALSE, 3344);

FARPROC fnLoadLibrary = GetProcAddress(GetModuleHandle(L"Kernel32"), "LoadLibraryW");

Inject(hProcess, fnLoadLibrary, L"T:\\test\\test.dll");

To continue building off the above example, once CreateRemoteThread is invoked, a call is made to WaitForSingleObject to wait for the thread to exit. Next, a call is made to GetExitCodeThread to obtain the result. Coincidentally, when LoadLibrary is passed into CreateRemoteThread, a successful invocation will result in the lpExitCode of GetExitCodeThread returning the base address of the loaded library in the context of the remote process. This works great for 32-bit applications, but not for 64-bit applications. The reason is that lpExitCode of GetExitCodeThread is a DWORD value even on 64-bit machines, hence the address is truncated.

At this point, three pieces of the puzzle are in place. To recap, the following problems have been solved:

- Loading the CLR using unmanaged code

- Executing arbitrary .NET assemblies from unmanaged code

- Injecting DLLs

Now that loading a DLL in a remote process is understood; discussion on how to start the CLR in a remote process can continue.

When LoadLibrary returns, the lock on the loader will be free. With the DLL in the address space of the remote process, exported functions can be invoked via subsequent calls to CreateRemoteThread; granted that the function signature matches LPTHREAD_START_ROUTINE. However, this invariably leads to more questions. How can exported functions be invoked inside a remote process, and how can pointers to these functions be obtained? Since GetProcAddress does not have a matching LPTHREAD_START_ROUTINE signature, how can the addresses of functions inside the DLL be obtained? Furthermore, even if GetProcAddress could be invoked, it still expects a handle to the remote DLL. How can this handle be obtained for 64-bit machines?

It is time to divide and conquer again. The following function reliably returns the handle (coincidentally the base address) of a given module in a given process on both x86 and x64 systems:

DWORD_PTR GetRemoteModuleHandle(const int processId, const wchar_t* moduleName)

{

MODULEENTRY32 me32;

HANDLE hSnapshot = INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE;

me32.dwSize = sizeof(MODULEENTRY32);

hSnapshot = CreateToolhelp32Snapshot(TH32CS_SNAPMODULE, processId);

if (!Module32First(hSnapshot, &me32))

{

CloseHandle(hSnapshot);

return 0;

}

while (wcscmp(me32.szModule, moduleName) != 0 && Module32Next(hSnapshot, &me32));

CloseHandle(hSnapshot);

if (wcscmp(me32.szModule, moduleName) == 0)

return (DWORD_PTR)me32.modBaseAddr;

return 0;

}

Knowing the base address of the DLL in the remote process is a step in the right direction. It is time to devise a strategy for acquiring the address of an arbitrary exported function. To recap, it is known how to call LoadLibrary and obtain a handle to the loaded module in a remote process. Knowing this, it is trivial to invoke LoadLibrary locally (within the calling process) and obtain a handle to the loaded module. This handle (which is also the base address of the module) may or may not be the same as the one in the remote process, even though it is the same library. Nevertheless, with some basic math, we can acquire the address for any exported function we wish. The idea is that although the base address of a module may differ from process to process, the offset of any given function relative to the base address of the module is constant. As an example, take the following exported function found in the Bootstrap DLL project in the source download:

__declspec(dllexport) HRESULT ImplantDotNetAssembly(_In_ LPCTSTR lpCommand)

Before this function can be invoked remotely, the Bootstrap.dll module must first be loaded in the remote process. Using Process Hacker, here is a screenshot of where the Windows loader placed the Bootstrap.dll module in memory when injected into Firefox:

Continuing with our strategy, here is a sample program that loads the Bootstrap.dll module locally (within the calling process):

#include <windows.h>

int wmain(int argc, wchar_t* argv[])

{

HMODULE hLoaded = LoadLibrary(

L"T:\\FrameworkInjection\\_build\\release\\x86\\Bootstrap.dll");

system("pause");

return 0;

}

When the above program is run, here is a screenshot of where Windows decided to load the Bootstrap.dll module:

The next step is, within wmain, to make a call to GetProcAddress to get the address of the ImplantDotNetAssembly function:

#include <windows.h>

int wmain(int argc, wchar_t* argv[])

{

HMODULE hLoaded = LoadLibrary(

L"T:\\FrameworkInjection\\_build\\debug\\x86\\Bootstrap.dll");

void* lpInject = GetProcAddress(hLoaded, "ImplantDotNetAssembly");

system("pause");

return 0;

}

The address of a function within a module will always be higher than the module's base address. Here is where basic math comes in to play. Below is a table to help illustrate:

| Firefox.exe | | Bootstrap.dll @ 0x50d0000 | | ImplantDotNetAssembly @ ? |

| test.exe | | Bootstrap.dll @ 0xf270000 | | ImplantDotNetAssembly @ 0xf271490 (lpInject) |

Test.exe shows that Bootstrap.dll is loaded at address 0xf270000, and that ImplantDotNetAssembly can be found in memory at address 0xf271490. Subtracting the address of ImplantDotNetAssembly from the address of Bootstrap.dll will give the offset of the function relative to the base address of the module. The math shows that ImplantDotNetAssembly is (0xf271490 - 0xf270000) = 0x1490 bytes into the module. This offset can then be added onto the base address of the Bootstrap.dll module in the remote process to reliably give the address of ImplantDotNetAssembly relative to the remote process. The math to compute the address of ImplantDotNetAssembly in Firefox.exe shows that the function is located at address (0x50d0000 + 0x1490) = 0x50d1490. The following function computes the offset of a given function in a given module:

DWORD_PTR GetFunctionOffset(const wstring& library, const char* functionName)

{

HMODULE hLoaded = LoadLibrary(library.c_str());

void* lpInject = GetProcAddress(hLoaded, functionName);

DWORD_PTR offset = (DWORD_PTR)lpInject - (DWORD_PTR)hLoaded;

FreeLibrary(hLoaded);

return offset;

}

It is worth noting that ImplantDotNetAssembly intentionally matches the signature of LPTHREAD_START_ROUTINE; as should all methods passed to CreateRemoteThread. Armed with the ability to execute arbitrary functions in a remote DLL, the logic to initialize the CLR has been put inside function ImplantDotNetAssembly in Bootstrap.dll. Once Bootstrap.dll is loaded in a remote process, the address of ImplantDotNetAssembly can be computed for the remote instance and then invoked via CreateRemoteThread. This is it, the final piece of the puzzle; now it is time to put it all together.

The main reason behind using an unmanaged DLL (Bootstrap.dll) to load the CLR is that if the CLR is not running in the remote process, the only way to start it is from unmanaged code (barring use of a scripting language such as Python, which has its own set of dependencies).

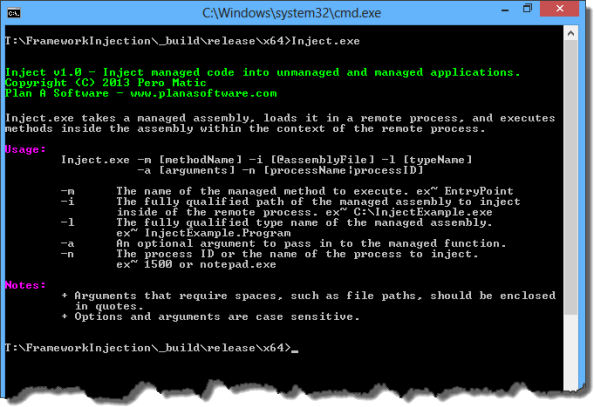

In addition, it would be nice for the Inject application to be flexible enough to accept input on the command line; because who would want to recompile every time their app changes? The Inject application accepts the following options:

| - | m | The name of the managed method to execute. ex~ EntryPoint |

| - | i | The fully qualified path of the managed assembly to inject inside of the remote process. ex~ C:\InjectExample.exe |

| - | l | The fully qualified type name of the managed assembly. ex~ InjectExample.Program |

| - | a | An optional argument to pass into the managed function. |

| - | n | The process ID or the name of the process to inject. ex~ 1500 or notepad.exe |

The wmain method for Inject looks like:

int wmain(int argc, wchar_t* argv[])

{

if (!ParseArgs(argc, argv))

{

PrintUsage();

return -1;

}

EnablePrivilege(SE_DEBUG_NAME, TRUE);

HANDLE hProcess = OpenProcess(PROCESS_ALL_ACCESS, FALSE, g_processId);

FARPROC fnLoadLibrary = GetProcAddress(GetModuleHandle(L"Kernel32"),

"LoadLibraryW");

Inject(hProcess, fnLoadLibrary, GetBootstrapPath());

DWORD_PTR hBootstrap = GetRemoteModuleHandle(g_processId, BOOTSTRAP_DLL);

DWORD_PTR offset = GetFunctionOffset(GetBootstrapPath(), "ImplantDotNetAssembly");

DWORD_PTR fnImplant = hBootstrap + offset;

wstring argument = g_moduleName + DELIM + g_typeName + DELIM +

g_methodName + DELIM + g_Argument;

Inject(hProcess, (LPVOID)fnImplant, argument);

FARPROC fnFreeLibrary = GetProcAddress(GetModuleHandle(L"Kernel32"),

"FreeLibrary");

CreateRemoteThread(hProcess, NULL, 0, (LPTHREAD_START_ROUTINE)fnFreeLibrary,

(LPVOID)hBootstrap, NULL, 0);

CloseHandle(hProcess);

return 0;

}

Below is a screenshot of the Inject.exe app being called to inject the .NET assembly InjectExample.exe into notepad.exe along with the command line that was used:

"T:\FrameworkInjection\_build\release\x64\Inject.exe" -m EntryPoint -i "T:\FrameworkInjection\_build\release\anycpu\InjectExample.exe" -l InjectExample.Program -a "hello inject" -n "notepad.exe"

It is worthwhile to mention and distinguish the differences between injecting a DLL that was built targetting x86, x64, or AnyCPU. Under normal circumstances, the x86 flavor of Inject.exe and Bootstrap.dll should be used to inject x86 processes, and the x64 flavor should be used to inject x64 processes. It is the responsibility of the caller to ensure the proper binaries are used. AnyCPU is a platform available in .NET. Targetting AnyCPU tells the CLR to JIT the assembly for the appropriate architecture. This is why the same InjectExample.exe assembly can be injected into either an x86 or x64 process.

Moving on to the fun stuff! There are a few prerequisites for getting the code to run using the default settings.

To build the code:

- Visual Studio 2012 Express +

- Visual Studio 2012 Express Update 1 +

To run the code:

- .Net Framework 4.0 +

- Visual C++ Redistributable for Visual Studio 2012 Update 1 +

- Windows XP SP3 +

To simplify the task of building the code, there is a file called build.bat in the source download that will take care of the heavy lifting provided the prerequisites have been installed. It will compile both the debug and release builds along with the corresponding x86, x64, and AnyCPU builds. Each project can also be built independently, and will compile from Visual Studio. The script build.bat will place the binaries in a folder named _build.

The code is also well commented. In addition, C++ 11.0 and .NET 4.0 were chosen because both runtimes will execute on all Windows OSes from XP SP3 x86 to Windows 8 x64. As a side note, Microsoft added XP SP3 support for the C++ 11.0 runtime in VS 2012 U1.

Traditionally, at this point papers tend to wind down and reflect on the techniques learned and other areas of improvement. While this is an excellent place to perform such an exercise, the author decided to do something different and present the reader with a basket full of:

As mentioned in the Introduction, .NET is a powerful language. For example, the Reflection API in .NET can be leveraged to obtain type information about assemblies. The significance of this is that .NET can be used to scan an assembly and return the valid methods that can be used for injection! The source download contains a .NET project called InjectGUI. This project contains a managed wrapper around our unmanaged Inject application. InjectGUI displays a list of running processes, decides whether to invoke the 32 or 64 bit version of Inject, as well as scans .NET assemblies for valid injectable methods. Within InjectGUI is a file named InjectWrapper.cs which contains the wrapper logic.

There is also a helper class called MethodItem which has the following definition:

public class MethodItem

{

public string TypeName { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

public string ParameterName { get; set; }

}

The following snippet from the ExtractInjectableMethods method will obtain a Collection of type List<MethodItem>, which matches the required method signature:

private void ExtractInjectableMethods()

{

Assembly asm = Assembly.LoadFile(ManagedFilename);

InjectableMethods =

(from c in asm.GetTypes()

from m in c.GetMethods(BindingFlags.Static |

BindingFlags.Public | BindingFlags.NonPublic)

where m.ReturnType == typeof(int) &&

m.GetParameters().Length == 1 &&

m.GetParameters().First().ParameterType == typeof(string)

select new MethodItem

{

Name = m.Name,

ParameterName = m.GetParameters().First().Name,

TypeName = m.ReflectedType.FullName

}).ToList();

}

Now that the valid (injectable) methods have been extracted, the UI should also know if the process to be injected is 32 or 64 bit. To do this, a little help is needed from the Windows API:

[DllImport("kernel32.dll", SetLastError = true, CallingConvention =

CallingConvention.Winapi)]

[return: MarshalAs(UnmanagedType.Bool)]

private static extern bool IsWow64Process([In] IntPtr process,

[Out] out bool wow64Process);

IsWow64Process is only defined on 64 bit OSes, and it returns true if the app is 32 bit. In .NET 4.0, the following property has been introduced: Environment.Is64BitOperatingSystem. This can be used to help determine if the IsWow64Process function is defined as seen in this wrapper function:

private static bool IsWow64Process(int id)

{

if (!Environment.Is64BitOperatingSystem)

return true;

IntPtr processHandle;

bool retVal;

try

{

processHandle = Process.GetProcessById(id).Handle;

}

catch

{

return false; }

return IsWow64Process(processHandle, out retVal) && retVal;

}

The logic inside the InjectGUI project is fairly straightforward. Some understanding of WPF and Dependency Properties is necessary to understand the UI, however, all the pertinent logic related to injection is in the InjectWrapper class. The UI is built using Modern UI for WPF, and the icons are borrowed from Modern UI Icons. Both projects are open source, and the author is affiliated with neither. Below is a screenshot of InjectGUI in action:

Closing Notes Part Deux

This concludes the discussion on injecting .NET assemblies into unmanaged processes. Don't cry because it's over. Smile ☺ because it happened. ~ William Shakespeare

History

- 21/06/2023: Migrated article & code to GitHub

- 22/06/2013: Initial release