Introduction

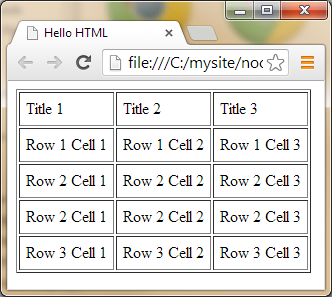

We have written our first web page using basic HTML in Writing Your First Code. We notice that web pages written out of HTML code alone look really really plain and unattractive. (Figure 1)

|

| Figure 1: Ugly Duckling |

How can we turn these "ugly ducklings" into "WOW"? (Figure 2) This article will get us started with the basic styling techniques for web pages. For that, we have to call upon the power of CSS.

|

| Figure 2: WOW |

CSS is the acronym for Cascading Style Sheets. It is the universal language for adding styles to web pages and is supported in all browsers. The latest standard is CSS3 which is completely

backwards-compatible with earlier versions. The CSS3 specification is

still under development by W3C and the latest version is Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) Snapshot 2010.

Getting Your Feet Wet

Start your favorite text editor and type in the HTML code as shown on the upper part of Figure 3. Once you are done, save it as .htm or .html file, launch it on a web browser, and you should see the outcome as shown on the lower part of Figure 3.

|

Figure 3: Web Page without Style |

Let's say your client saw that web page in Figure 3 and asks that the largest heading to be of blue color and be placed in the center of the web page. Can you do it? HTML alone is out of question. Fret not! Add the following CSS code (highlighted in blue in Figure 4) into the HTML code and you will make your client happier.

|

Figure 4: Web Page with Simple Style |

Basic CSS Syntax

You have just added a CSS style to your web page. Let's examine the basic CSS syntax while recalling the processes:

Step 1 - Add an opening <style> tag followed by a closing </style> in the head section as indicted by the blue zone in the upper part of Figure 4. This is the area where set of CSS rules will reside.

<style>

</style>

Note that /* and */ are used to enclose comments in CSS. Comments are used to explain code, and are ignored by browsers.

Step 2 - Select the HTML element that we want to style. In this example, it is the <h1> tag, so we shall type h1 which is called the selector in CSS terminology. A pair of braces ({ }) after h1 is used to wrap style declarations for the h1 selector.

<style>

h1

{

}

</style>

Step 3 - Add 2 style declarations, one for setting the color of <h1> content to blue and another for centralizing it.

<style>

h1

{

color:blue;

text-align:center;

}

</style>

Each

declaration consists of a

property and a

value separated by a colon (

:) and ends with a semicolon (

;). In our example,

color is the property and

blue is its value. This is illustrated in the following diagram:

| Property | | Value | |

| color | : | blue | ; |

We have just covered the basic syntax of CSS and processes. Let's take stock:

<style>

h1

{

color:blue;

text-align:center;

}

</style> /* End of CSS block */

To add styles to another HTML element, say <p>, simply add p as a selector with corresponding style declarations before or after the h1 block as shown below. The order does not matter.

<style>

h1

{

color:blue;

text-align:center;

}

p

{

color:green;

text-align:right;

}

</style>

Seeing that you are doing a good job, your client demands more, "I would like the second largest text to be of red color and be left aligned. Can you do it?" "Yes," (what else can you say?) Your client has Figure 5 in mind. I shall leave it as your homework. ;P

|

Figure 5: Web Page with More Style |

CSS Selectors

CSS selectors allow us to find, select and declare stylistic descriptions to HTML elements.

The Element Selector

In our previous example, we have used CSS selectors by their HTML tag names, i.e. h1, h3, and p, to apply styles to the respective HTML elements. Bear in mind that a web page can contain multiple of these tags, especially the <p> tags. The p selector will apply the same styles to all the <p> tags across the whole web page indiscriminately. That means all the <p> tags will be of green color and be right-aligned. This blanket way of applying styles makes it impossible to customize different styles to individual paragraphs as they are all affected by the p selector. (Figure 6)

(Insert the following code into a HTML document as described in the previous sections.)

|

Figure 6: Effect of Element Selector |

To overcome this limitation, we shall introduce 2 more selectors - id and class.

The id Selector

Each HTML tag has an id attribute that can carries a name that uniquely distinguishes itself from the others. For example, if there are 2 <p> tags that exist in an HTML document, we may give one of them an id name of "para1" while another "para2". To select them in the CSS code, add a # before their id names. So the selector names for "para1" and "para2" will be "#para1" and "#para2" respectively. In this way, we can apply different CSS styles to them using their id names as selectors. (Figure 7)

|

Figure 7: Effect of id Selector |

You may notice that the 2 paragraphs with id names of para1 and para2 remain centered even though there are no text-align properties specified in their respective selectors. In this situation, they have inherited the text-align property from their generic parent, i.e. the <p> tag, which has been styled by the p selector.

Take note of the following points with regard to the id selector:

- Do not start a id name with a number

- id name should be unique within a page

- Use id selector when you want to find a single element in a page

The class Selector

Similarly, each HTML tag also has a class attribute that can carries a name that identifies the group that it belongs to. For example, if there are 4 <p> tags exist in a HTML document, we

may give 2 of them a class name of "group1". To

select them in the CSS code, add a period character (.) before their class names. So

the selector name for "group1" is ".group1". In this way, we can apply a set of CSS styles to a group of HTML elements that share the same class name by using their class name as selector. (Figure 8)

|

Figure 8: Effect of class Selector |

Take note of the following points with regard to the class selector:

- Do not start a class name with a number

- Use class selector when you want to find a group of elements in a page

Chaining of Selectors

If several elements share the same styles, we can chain them up to minimize code. (Figure 9)

|

Figure 9: Chaining of Selectors |

CSS Placements

So far, you have been told to place CSS style sheets internally inside the head section of HTML documents. They are called Internal Style Sheets. In fact, there are 2 more ways of placing CSS style sheets - External Style Sheet and Inline Style Sheet.

Internal Style Sheet

We are already very familiar with internal style sheets. It should be used when a single HTML document has a unique style. However, this is very inefficient for situations where many HTML documents share the same style. For that, we should go for the external style sheets.

External Style Sheet

As the name implies, external style sheets reside outside of any HTML documents. Each document will link to the appropriate external style sheets using the <link> tag inside the head section.

Let;s see how it is being done.

We will "cut and paste" the CSS code inside the <style> and </style> tags from the HTML document in Figure 9 to a text editor. Save this text file as "mystyle.css" inside the same folder as the HTML document. Note that .css is the file extension for all external style sheets.

h1,h2,p

{

color:red;

text-align:right;

}

The CSS style sheet has been removed from the HTML document. To link your HTML document to "mystyle.css", add the following statement inside the head section of the HTML document:

<link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="mystyle.css">

Launch the HTML document in a browser and you should see the same web page as shown in Figure 9.

An external style sheet is ideal when we want to apply a uniform style across multiple web pages of a website. We can alter the look and feel of an entire website by simply changing one file, i.e. the external style sheet. A great relief for web maintenance.

Inline Style Sheet

Inline style sheet places style declarations using style attribute of HTML tags as shown in the following example:

<p style="color:red;text-align=center;">Inline Style Sheet</p>

However, this way of embedding CSS in HTML tags has rekindled the old nightmare of mixing content with presentation and eradicates any benefits of introducing CSS. So you should avoid inline style sheet as much as possible.

Precedence of Style Sheets

It is not unimaginable that an HTML element may have multiple styles specified for it through a mix of inline, internal, and external style sheets. Under such circumstances, which style should that "bewildered" HTML element follow? Here the order of precedence come into play (in descending order of priority):

- Inline style sheet (inside an

HTML element) - Internal style sheet (inside the

head section) - External style sheet (in an external .css file)

- Browser default (not specified in any style sheet)

There is one caveat though - if the link to the external style sheet is placed below the internal style sheet, the former will take precedence.

Hard to remember? Fret not, just remember this rule of thumb of mine - "Whoever is the nearest to the element wins". Got it?

CSS Properties

We have used "color" and "text-align" in the preceding examples. They are just 2 of the many CSS properties. Property names in CSS are fairly intuitive, i.e., they do what their names suggest. We shall explore 3 categories of them - backgrounds, text, and fonts.

CSS Backgrounds

The background effects of any web pages can be defined by the following CSS background properties:

- background-color

We use background-color property to set the background color of any HTML elements, including the <body> tags.

|

Figure 10: Effect of background-color |

- background-image

We use background-image property to embed a background image to any HTML elements, Add the following code snippet into an HTML document, change the url parameter to point to an image file:

body{background-image:url("logo250x135.gif");}

When it is displayed in the browser, the background of the whole web page will be tiled with the image. (Figure 11)

|

Figure 11: Effect of background-image |

- background-repeat

To repeat the background image only horizontally, use background-repeat:repeat-x.

body

{

background-image:url("logo250x135.gif");

background-repeat:repeat-x;

}

The effect is shown in Figure 12.

|

Figure 12: Effect of background-repeat:repeat-x; |

To repeat the background image only vertically, change the value of background-repeat property to repeat-y.

background-repeat:repeat-y;

To display the background-image on the top-left hand corner of the screen without any repetition, change the value of background-repeat property to no-repeat.

background-repeat:no-repeat;

- background-position

To fix the background image to some position on the screen, set the background-position property to the appropriate value like "top right".

body

{

background-image:url("logo250x135.gif");

background-repeat:no-repeat;

background-position:top right;

}

The effect is shown in Figure 13.

|

Figure 13: Effect of background-position:top right; |

CSS Text

The text effect of any web pages can be defined by the following CSS properties:

- color

The color property is used to set the text color of any HTML elements, We have already seen its many examples.

- text-align

The text-align property is used to set the horizontal alignment of a text. It can take one of 4 values - center, left, right, or justified. We have also seen its many examples.

- text-decoration

The text-decoration property is used to set or unset decorations for text content of any HTML element. It can take one of 4 values - overline, line-through, underline, none. (Figure 14)

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<style>

#overline{text-decoration:overline;}

#strikethrough{text-decoration:line-through;}

#underline{text-decoration:underline;}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<p id="overline">Under one roof</p>

<p id="strikethrough">Cancel an appointment</p>

<p id="underline">On solid footing</p>

</body>

</html>

|

Figure 14: Effect of text-decoration |

The none value is used to remove default underlines from hyperlinks.

- text-transform

The text-transform is used to transform text content of any HTML elements into either uppercase, lowercase, or capitalize depending on its value. (Figure 15)

|

Figure 15: Effect of text-transform |

- text-indent

The text-indent property is used to specify the amount of indentation of the first line of a text. (Figure 16)

|

Figure 16: Effect of text-indent |

CSS Fonts

The font effect of a text can be defined by the following CSS properties:

- font-family

The font-family property is used to set the font for some texts in an HTML document. There are two types of font-family names:

- Individual font-family like "Times New Roman", "Verdana", "arial", etc.

- Collection of font-families like "sans-serif", "Serif", "fantasy", "monospace", etc.

(Refer CSS Font Stack)

It is common to define a few font names for the font-family property. The list of font names are separated with commas. For fonts that have white space in their name, use quotes to enclose the names, such as "Times New Roman" in the following example:

font-family:"Times New Roman",Cambria,Serif;

if the browser does not support the first font, it will fall back to the second one. The rule of thumb is that you should always start with an individual font-family name that you want, and end with a name that specifies the collection of fonts that the preceding fonts belong to. This will allow the browser to pick a similar font in the same font collection in the event that all preceding fonts are not available.

Try out the following example and see the outcome on a browser.

|

Figure 17: Effect of font-family |

- font-style

The font-style property takes one of three values - normal, italic, or oblique. See their respective effects by adding the following CSS code into the previous example of Figure 17.

.serif

{

font-family:"Times New Roman",Georgia,serif;

font-style:normal;

}

.sansserif

{

font-family:Arial,"Century Gothic",sans-serif;

font-style:italic;

}

.monospace

{

font-family:"Courier New",Monaco,monospace;

font-style:oblique;

}

|

Figure 18: Effect of font-style |

- font-size

We can use the font-size property to set the size of text using any one of the 3 units of measurement - pixel, em, or percentage. (Figure 19)

|

Figure 19: Effect of font-size |

Let's examine the output of Figure 19 on a browser. Paragraph 1 is shown in font size of 100% as it has been set as default using the body selector in the CSS. In contrast, paragraph 2 is set to the font size of 50% as shown. For paragraphs 3 and 4, they appear identical in font size. Looking at their respective CSS declarations, the former is being set to 16 pixels while the later 1 em. In other words, the measurement of 1 em is equal to 16 pixels.

Points to Note

It is time to take stock of today's learning by noting these salient points:

- CSS is not case sensitive

- Selector names cannot start with a number

- Avoid using inline style sheets as much as possible

We shall pause for a breather.

Reference