So in the last bog, we wrapped up a part of this series, which was to do with the functional programming aspect of F#. We will now begin the “Imperative Programming” section. This will not be a huge section and will not involve that many posts, and hopefully will be more familiar to people that may have come from C# or another .NET language, just like I have.

F# Standard Behaviour

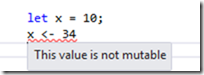

The default behaviour in F# is for non mutable values. That it once a value has been bound, say using a let binding, you are not able to change its value. So if you try and assign a new value to the bound value, you will get a compiler error (that is unless you do one of the 2 things we are about to discuss below):

There are of course ways to make things mutable in F#, and this really comes down to 2 different approaches:

- Mutable

- Ref cells

We will be looking at both of these approaches

Mutable

As we just saw we can not update a non mutable value. What F# does allow us to do in this case, is to simply use a mutable keyword, which makes the value that it is used against mutable.

Here is the previous example rewritten to use the mutable keyword:

let mutable x = 10;

printfn "before x was %A" x

x <- 34

printfn "now x is %A" x

Which when run gives the following output:

You may use the mutable keyword in a number of different places, such as

Though there are some limitations when working working with mutable values, one that I have read about a bit ,is that local mutable values may not be captured by closured, and this is where Ref cells are preferred. This comes from Tomas Petricek, who outside of Dom Syme, is probably the most knowledgeable F# guy on the planet, so I think its a fairly safe bit of information to trust.

Ref Cells

MSDN says this about Ref Cells. “Ref Cells are storage locations that enable you to create mutable values using reference semantics.” Which is pretty much how I would have said it, so fair play MSDN thanks. You can kind of think of ref cells of a sort of pointer type idea, as you may find in C/C++ which support referencing and dereferencing. Though in F# we do not need to resort to using actual pointers. Another quite familiar thing is that you may see things like byref, which you may see in other languages such as C# where it uses the ref keyword. They are equivalent in C# you use ref to state you want something passed by reference, whilst in F# the generic type is byref, but they do the same job.

Declaring And Dereferencing Ref Cells

To declare and dereference a ref cell is quite easy, all we need to do is something like the following:

let theRefValue = ref 6

printfn "theRefValue before = %A" theRefValue.Value

theRefValue := 24

printfn "theRefValue after = %A" theRefValue.Value

let deRef = !theRefValue

printfn "deRef = %A" deRef

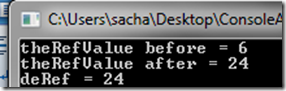

Where the following can be seen:

- We use the

ref keyword to declare a ref value - We use the assignment operator “:=” to assign a new value to the

ref cell - We use the dereference operator “!” which gets us the value of the

ref cell - That we made use of a Value property, which allows us to get the value of a

ref cell

When we run the above code we will get something like this:

Helper Properties

Ref cells also come with a couple of handy properties, such as

Both of which are get/set, so you can use them to set the ref cell value. Here is an example:

let theRefValue = ref 1

printfn "theRefValue before = %A" theRefValue.Value

theRefValue.contents <- 2

printfn "theRefValue after theRefValue.contents <- 2 = %A" theRefValue.Value

theRefValue.Value <- 3

printfn "theRefValue after theRefValue.Value <- 3 = %A" theRefValue.Value

Which when run will give the following results:

Asking For A Ref Cell Parameter

Another thing you may want to do is demand that a certain function require a ref cell. This is done using the byref keyword (ref keyword in C#). When you use this keyword in F#, you must either pass a ref cell, or the address of one. The address of one is achieved using the “&” operator, like it is in C++.

Here is an example where I have written a function that requires a byref value. It can be seen that the 1st example usage does not give us what we want as it is not a ref cell.

open System

module DemoTypes =

type ChangeORama(newValue) =

member this.Change(orig : string byref) =

orig <- newValue

......

......

let changer = new ChangeORama("changed")

let mutable original ="I like F#"

printfn "original = %A" original

changer.Change(ref original)

printfn "original using ref = %A\r\n" original

let mutable original2 ="I also like C#"

printfn "original2 = %A" original2

changer.Change(&original2)

printfn "original2 = %A\r\n" original2

let original3 = ref "I still like F#"

printfn "original3 = %A" original3

changer.Change(original3)

printfn "original3 using ref/deref = %A" !original3

Which when run gives us this result: