This is the third in a series of articles about subqueries. In this article, we discuss subqueries in the WHERE clause. Other articles discuss their uses in other clauses.

Using Subqueries in the WHERE Clause

It is very common to use subqueries in the WHERE clause. A common use is to test for existence using EXISTS or IN. In some cases, it may make sense to rethink the query and use a JOIN, but you should really study both forms via the query optimizer before making a final decision.

The comparison modifiers ANY and ALL can be used with greater than, less than, or equals operators. Doing so provides a means to compare a single value, such as a column, to one or more results returned from a subquery.

Let’s now explore these in detail.

Exist and Not Exists

The EXISTS condition is used in combination with a subquery. It returns TRUE whenever the subquery returns one or more values.

In its simplest form, the syntax for the EXISTS condition is:

WHERE EXISTS (sub query)

Suppose we need to return all sales orders written by sales people with sales year to date greater than three million dollars. To do so, we can use the EXISTS clause as shown in this example:

SELECT SalesOrderID,

RevisionNumber,

OrderDate

FROM Sales.SalesOrderHeader

WHERE EXISTS (SELECT 1

FROM sales.SalesPerson

WHERE SalesYTD > 3000000

AND SalesOrderHeader.SalesPersonID

= Sales.SalesPerson.BusinessEntityID)

When this SQL executes, the following comparisons are made:

- The

WHERE clause returns all records where the EXISTS clause is TRUE. - The

EXIST clause uses a correlated sub query. The outer query is correlated to the inner query by SalesPersonID. - Only

SalesPersons with SalesYTD greater than three million are included in the results. - The

EXISTS clause returns TRUE if one or more rows are returned by the sub query.

The EXISTS condition is a membership condition in the sense it only returns TRUE if a result is returned. Conversely, if we want to test for non-membership we can use NOT EXISTS.

NOT EXISTS returns TRUE if zero rows are returned. So, if we want to find all sales orders that were written by salespeople that didn’t have 3,000,000 in year-to-date sales, we can use the following query:

SELECT SalesOrderID,

RevisionNumber,

OrderDate

FROM Sales.SalesOrderHeader

WHERE NOT EXISTS (SELECT 1

FROM sales.SalesPerson

WHERE SalesYTD > 3000000

AND SalesOrderHeader.SalesPersonID

= Sales.SalesPerson.BusinessEntityID)

WHAT Happens to NULL?

When the subquery returns a null value what does EXISTS return: NULL, TRUE, or FALSE?

To be honest, I was surprised.

I was sure it would return NULL, but to my surprise I learned it returns TRUE. Therefore, if your subquery returns a NULL value, the EXISTS statement resolves to TRUE. In the following example, all the SalesOrderHeader rows are returned as the WHERE clause essentially resolved to TRUE:

SELECT SalesOrderID,

RevisionNumber,

OrderDate

FROM Sales.SalesOrderHeader

WHERE EXISTS (SELECT NULL)

As we study the IN operator, we’ll see this behavior is unique to the EXISTS clause.

IN and NOT IN

We first studied the IN operator back in the lesson, How to Filter Your Query Results. When used in subqueries, the mechanics of the IN and NOT IN clause are the same. Here is a summary from that article.

IN and NOT IN Review

The IN operator is considered a membership type. The membership type allows you to conduct multiple match tests compactly in one statement. For instance, consider if you have a couple spelling variations for the leader of the company such as ‘Owner’, ‘President’, and ‘CEO.’ In cases like this, you could use the in operator to find all matches:

ContactTitle IN ('CEO', 'Owner', 'President')

The above will math or return turn if the contact title is either ‘CEO’, ‘Owner’, or ‘President.’ To use the IN comparison operator, separate the items which to test for with commas and be sure to enclose them in parenthesis. The full SQL statement for our example is:

SELECT CompanyName, ContactName, ContactTitle

FROM Customers

WHERE ContactTitle IN ('CEO', 'Owner', 'President');

Note: The above query isn't meant for the Adventure works database.

Using IN with Sub Queries

When used with subqueries, the list of values is replaced with a subquery. The advantage to using a sub query in this case is that it helps to make your queries more data driven and less brittle.

What I mean is you don’t have to hard code values.

If for instance you’re doing a query to find sales order by top sales people, the non-sub query way to use the IN statement is:

SELECT SalesOrderID,

OrderDate,

AccountNumber,

CustomerID,

SalesPersonID,

TotalDue

FROM Sales.SalesOrderHeader

WHERE SalesPersonID IN (279, 286, 289)

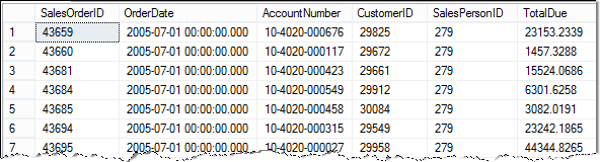

whose results are

But now, since we know about subqueries, we can use the following to obtain the same list:

SELECT SalesOrderID,

OrderDate,

AccountNumber,

CustomerID,

SalesPersonID,

TotalDue

FROM Sales.SalesOrderHeader

WHERE SalesPersonID IN (SELECT BusinessEntityID

FROM Sales.SalesPerson

WHERE Bonus > 5000)

The advantage is that as sales persons sell more or less, the list of sales person IDs returned adjusts.

Just like with other queries, you can create a correlated sub query to be used with the IN clause. Here is the same query we used with the EXIST clause.

It returns all sales orders written by sales people with sales year to date greater than three million dollars, but now we use the IN clause:

SELECT SalesOrderID,

RevisionNumber,

OrderDate

FROM Sales.SalesOrderHeader

WHERE SalesPersonID IN (SELECT SalesPerson.BusinessEntityID

FROM sales.SalesPerson

WHERE SalesYTD > 3000000

AND SalesOrderHeader.SalesPersonID

= Sales.SalesPerson.BusinessEntityID)

As IN returns TRUE if the tested value is found in the comparison list, NOT IN returns TRUE if the tested value is not found. Taking the same query from above, we can find all Sales orders that were written by salespeople that didn’t write 3,000,000 in year-to-date sales, we can write the following query:

SELECT SalesOrderID,

RevisionNumber,

OrderDate

FROM Sales.SalesOrderHeader

WHERE SalesPersonID NOT IN (SELECT SalesPerson.BusinessEntityID

FROM sales.SalesPerson

WHERE SalesYTD > 3000000

AND SalesOrderHeader.SalesPersonID

= Sales.SalesPerson.BusinessEntityID)

WHAT Happens to NULL with IN?

When the comparison list only contains the NULL value, then any value compared to that list returns false.

For instance:

SELECT SalesOrderID,

RevisionNumber,

OrderDate

FROM Sales.SalesOrderHeader

WHERE SalesOrderID IN (SELECT NULL)

returns zero rows. This is because the IN clause always returns false. Contrast this to EXISTS, which returns TRUE even when the subquery returns NULL.

Comparison Modifiers

Comparison operators such as greater than, less than, equal, and not equal can be modified in interesting ways to enhance comparisons done in conjunction with WHERE clauses.

Rather than using >, which only makes sense when comparing to a single (scalar) value, you can use > ANY or > ALL to compare a column value to a list results returned from sub query.

Using the > ANY Modifier

The comparison operator > ANY means greater than one or more items in the list. This is the same as saying it is greater than MIN value of the list. So the expression...

Sales > ANY (1000, 2000, 2500)

...returns TRUE if Sales are greater than 1000 as this expression is equivalent to:

Sales > MIN(1000, 2000, 2500)

Which simplifies to:

Sales > 1000

Note: You may see some queries using SOME. Queries using SOME return the same result as those using ANY. Simply said > ANY is the same as > SOME.

Let’s do an example using the Adventure works database. We’re going to find all products which may have a high safety stock level. To do so, we’ll look for all products that have a SafetyStockLevel that is greater than the average SafetyStockLevel for various DaysToManufacture.

The query to do this is:

SELECT ProductID,

Name,

SafetyStockLevel,

DaysToManufacture

FROM Production.Product

WHERE SafetyStockLevel > ANY (SELECT AVG(SafetyStockLevel)

FROM Production.Product

GROUP BY DaysToManufacture)

When this subquery is run, it first calculates the Average SafetyStockLevel. This returns a list of numbers. Then for each product row in the outer query SafetyStockLevel is compared. If it is greater than one or more from the list, then include it in the results.

Like me, you may at first think that > ANY is redundant, and not needed. It is equivalent to > MIN(…), right?

What I found out is that though it is equivalent in principle, you can’t use MIN. The statement:

SELECT ProductID,

Name,

SafetyStockLevel,

DaysToManufacture

FROM Production.Product

WHERE SafetyStockLevel > MIN((SELECT AVG(SafetyStockLevel)

FROM Production.Product

GROUP BY DaysToManufacture))

won’t run. It returns the error, “Cannot perform an aggregate function on an expression containing an aggregate or a subquery.”

Using the > ALL Modifier

The > ALL modifier works in a similar fashion except it returns the outer row if its comparison value is greater than every value returned by the inner query.

The comparison operator > ALL means greater than the MAX value of the list. Using the example above, then

Sales > ALL (1000, 2000, 2500)

is equivalent to:

Sales > MAX(1000, 2000, 2500)

Which returns TRUE if Sales > 2500

In this example, we’ll return all SalesPeople that have a bonus greater than ALL salespeople whose year-to-date sales were less than a million dollars.

SELECT p.BusinessEntityID,

p.FirstName,

p.LastName,

s.Bonus,

s.SalesYTD

FROM Person.Person AS p

INNER JOIN Sales.SalesPerson AS s

ON p.BusinessEntityID = s.BusinessEntityID

WHERE s.Bonus > ALL (SELECT Bonus

FROM Sales.SalesPerson

WHERE Sales.SalesPerson.SalesYTD

< 1000000)

Summary of Various Comparison Modifiers

You can use comparison modifiers with other operators, such as equals. Use the chart below to get a better understanding through the examples. I’ve listed all the combinations, even those that don’t make too much sense.

When reviewing the example, assume the sub query returns a list of three numbers: 1,2,3.

Some combinations of these comparison modifiers are downright goofy. For instance, I can’t imagine using “= ALL” or “<> ANY.” The others make sense, and as we have shown, you can really use MAX or MIN as legal equivalent statements. ANY and ALL do have their places!

Out of all of the items we discussed today, I’ve used EXISTS and NOT EXISTS the most with subqueries. I use IN quite a bit, but usually with a static list, not with subqueries.