Contents

In my previous article, I explained in detail the ASP.NET request processing architecture. If you recall, the article traced a request for an ASP.NET page from the moment it was issued from the browser until it reached the HTTP Handler. So, what happens next? The answer is the ASP.NET page life cycle starts…

In this article, I will discuss in detail the ASP.NET page life cycle and the ASP.NET Viewstate as an integrated unit.

It is strongly recommended that you read the complete article; however, if –and only if – you consider yourself very familiar with the inner workings of Viewstate and the page life cycle, and you want to go directly to the “cream” of the advanced scenarios, then you skip your way through to the “Viewstate Walkthroughs” section.

In its very basic form, Viewstate is nothing more than a property which has a key/value pair indexer:

Viewstate[“mystringvariable”] = “myvalue”;

Viewstate[“myintegervariable”] = 1;

As you can see, the indexer accepts a string as a key and an object as the value. The ViewState property is defined in the “System.Web.UI.Control” class. Since all ASP.NET pages and controls derive from this class, they all have access to the ViewState property. The type of the ViewState property is “System.Web.UI.StateBag”.

The very special thing about the StateBag class is the ability to “track changes”. Tracking is, by nature, off; it can be turned on by calling the “TrackViewState()” method. Once tracking is on, it cannot be turned off. Only when tracking is on, any change to the StateBag value will cause that item to be marked as “Dirty”.

Info: In case you are wondering (and you should be) about the reason behind this “tracking” behavior of the StateBag, do not worry; this will be explained in detail along with examples about how tracking works, in the next sections. |

When dealt within the context of ASP.NET, the Viewstate can be defined as the technique used by an ASP.NET web page to remember the change of state spanning multiple requests. As you know, ASP.NET is a stateless technology; meaning that two different requests (two postbacks) to the same web page are considered completely unrelated. This raises the need of a mechanism to track the change of state for this web page between the first and the second request.

The Viewstate of an ASP.NET page is created during the page life cycle, and saved into the rendered HTML using in the “__VIEWSTATE” hidden HTML field. The value stored in the “__VIEWSTATE” hidden field is the result of serialization of two types of data:

- Any programmatic change of state of the ASP.NET page and its controls. (Tracking and “

Dirty” items come into play here. This will be detailed later.)

- Any data stored by the developer using the Viewstate property described previously.

This value is loaded during postbacks, and is used to preserve the state of the web page.

| Info: The process of creating and loading the Viewstate during the page life cycle will be explained in detail later. Moreover, what type of information is saved in the Viewstate is also to be deeply discussed. |

One final thing to be explained here is the fact that ASP.NET server controls use Viewstate to store the values of their properties. What does this mean? Well, if you take a look at the source code of the TextBox server control, for example, you will find that the “Text” property is defined like this:

public string Text

{

get { return (string)ViewState["Text"]; }

set { ViewState["Text"] = value; }

}

You should apply this rule when developing your own server controls. Now, this does not mean that the value of the “Text” property set at design time is saved in the rendered serialized ViewState field. For example, if you add the following TextBox to your ASP.NET page:

<asp:TextBox runat="server" ID="txt" Text="sometext" />

According to the fact that the “Text” property uses Viewstate to store its value, you might think that the value is actually serialized in the __VIEWSTATE hidden field. This is wrong because the data serialized in the hidden __VIEWSTATE consists only of state changes done programmatically. Design time data is not serialized into the __VIEWSTATE (more on this later). For now, just know that the above declaration of the “Text” property means that it is utilizing Viewstate in its basic form: an indexed property to store values much like the Hashtable collection does.

Generating the compiled class

The first step (actually, step 0 as explained in the info block below) of the life cycle is to generate the compiled class that represents the requested page. As you know, the ASPX page consists of a combination of HTML and Server controls. A dynamic compiled class is generated that represents this ASPX page. This compiled class is then stored in the “Temporary ASP.NET Files” folder. As long as the ASPX page is not modified (or the application itself is restarted, in which case the request will actually be the first request and then the generation of the class will occur again), then future requests to the ASPX page will be served by the same compiled class.

| Info: If you have read my previous article about request processing, you will likely recall that the last step of the request handling is to find a suitable HTTP Handler to handle the request. Back then, I explained how the HTTP Handler Factory will either locate a compiled class that represents the requested page or will compile the class in the case of the first request. Well, do you see the link? This is the compiled class discussed here. So, as you may have concluded, this step of generating the compiled class actually occurs during the ASP.NET request handling architecture. You can think of this step as the intersection between where the ASP.NET request handling architecture stops and the ASP.NET page life cycle starts. |

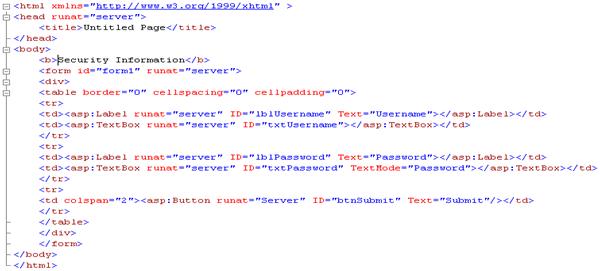

This compiled class will actually contain the programmatic definition of the controls defined in the aspx page. In order to fully understand the process of dynamic generation, let us consider the following example of a simple ASPX page for collecting the username and the password:

Now, upon the first request for the above page, the generated class is created and stored in the following location:

C:\WINDOWS\Microsoft.NET\Framework\v2.0.50727\Temporary ASP.NET Files\

<application name>\< folder identifier1>\< file identifier1>.cs

The compiled class “DLL” is also created in the same location with the same file identifier, as follows:

C:\WINDOWS\Microsoft.NET\Framework\v2.0.50727\Temporary ASP.NET Files\

<application name>\< folder identifier1>\< file identifier1>.dll

As you can see, the generated class and its corresponding DLL are created, and will serve any new request for the ASPX page until one of the following conditions occur:

- The ASPX file is modified

- The application is restarted, for example, as a result of IIS reset or app domain restart

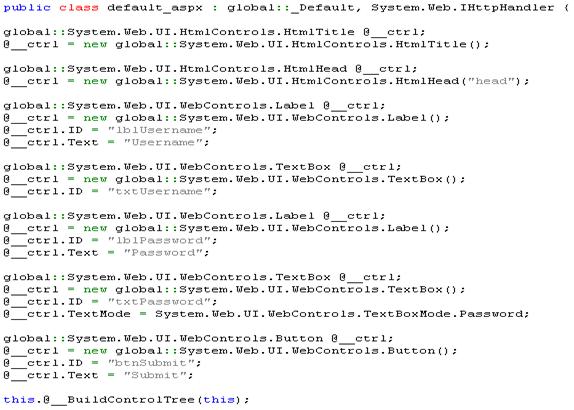

The following code is extracted from the compiled class. Note that the code is reformatted and “cleaned up” for presentation purposes.

OK, so now is the really interesting part. Start examining the code above, and you will be able to notice the following:

- The class – unsurprisingly – inherits from the “

System.Web.IHttpHandler”. As explained earlier, this makes it eligible for acting as an HTTP Handler for the request.

- All the controls – both HTML and Web Controls – are defined in the class. Notice how the static properties (such as “

Text” and “TextMode”) are set inside the class. This is very important to remember because this is a vital point when discussing the Viewstate later in this article.

- The “

BuildControlTree” is called to create the control hierarchy. As you may know, controls inside an ASPX page are built into a tree hierarchy. For example, in the above example, the hierarchy would be as follows: The root parent is the page class itself, under which the direct child controls are the HTML Literal (the "b" tag) and the HTML Form. The HTML Form, in its turn, has two direct child controls which are the HTML Literal (the "div" tag) and the HTML Table. The HTML Table, in its turn, has child controls such as the Web Control for the username label and the Web Control for the password label, and so on until the complete hierarchy is built. Again, this is a very important point to remember because it will be revisited when discussing the Viewstate.

PreInit (New to ASP.NET 2.0)

The entry point of the page life cycle is the pre-initialization phase called “PreInit”. This is the only event where programmatic access to master pages and themes is allowed. Note that this event is not recursive, meaning that it is accessible only for the page itself and not for any of its child controls.

Init

Next is the initialization phase called “Init”. The “Init” event is fired reclusively for the page itself and for all the child controls in the hierarchy (which is created during the creation of the compiled class, as explained earlier). Note that against many developers’ beliefs, the event is fired in a bottom to up manner and not an up to bottom within the hierarchy. This means that following up with our previous example, the “Init” event is fired first for the most bottom control in the hierarchy, and then fired up the hierarchy until it is fired for the page itself. You can test this behavior yourself by adding a custom or user control to the page. Override the “OnInit” event handler in both the page and the custom (or user) control, and add break points to both event handlers. Issue a request against the page, and you will notice that the event handler for the control will be fired up before that of the page.

InitComplete (New to ASP.NET 2.0)

The initialization complete event called “InitComplete” signals the end of the initialization phase. It is at the start of this event that tracking of the ASP.NET Viewstate is turned on. Recall that the StateBag class (the Type of Viewstate) has a tracking ability which is off by default, and is turned on by calling the “TrackViewState()” method. Also recall that, only when tracking is enabled will any change to a Viewstate key mark the item as “Dirty”. Well, it is at the start of “InitComplete” where “Page.TrackViewState()” is called, enabling tracking for the page Viewstate.

| Info: Later, I will give detailed samples of how the Viewstate works within each of the events of the life cycle. These examples will hopefully aid in understanding the inner workings of the Viewstate. |

LoadViewState

This event happens only at postbacks. This is a recursive event, much like the “Init” event. In this event, the Viewstate which has been saved in the __VIEWSTATE during the previous page visit (via the SaveViewState event) is loaded and then populated into the control hierarchy.

LoadPostbackdata

This event happens only at postbacks. This is a recursive event much like the “Init” event. During this event, the posted form data is loaded into the appropriate controls. For example, assume that, on your form, you had a TextBox server control, and you entered some text inside the TextBox and posted the form. The text you have entered is what is called postback data. This text is loaded during the LoadPostbackdata event and handed to the TextBox. This is why when you post a form, you find that the posted data is loaded again into the appropriate controls. This behavior applies to most controls like the selected item of a drop down list or the “checked” state of a check box, etc…

A very common conceptual error is the thought that Viewstate is responsible for preserving posted data. This is absolutely false; Viewstate has nothing to do with it. If you want a proof, disable the Viewstate on your TextBox control or even on the entire page, and you will find that the posted data is still preserved. This is the virtue of the LoadPostbackdata event.

PreLaod (New to ASP.NET 2.0)

This event indicates the end of system level initialization.

Load

This event is recursive much like the “Init” event. The important thing to note about this event is the fact that by now, the page has been restored to its previous state in case of postbacks. That is because the LoadViewState and the LoadPostbackdata events are fired, which means that the page Viewstate and postback data are now handed to the page controls.

RaisePostbackEvent

This event is fired only at postbacks. What this event does is inspect all child controls of the page and determine if they need to fire any postback events. If it finds such controls, then these controls fire their events. For example, if you have a page with a Button server control and you click this button causing a postback, then the RaisePostbackEvent inspects the page and finds that the Button control has actually raised a postback event – in this case, the Button's Click event. The Button's Click event is fired at this stage.

LoadComplete (New to ASP.NET 2.0)

This event signals the end of Load.

Prerender (New to ASP.NET 2.0)

This event allows for last updates before the page is rendered.

PrerenderComplete (New to ASP.NET 2.0)

This event signals the end of “Prerender”.

SaveViewstate

This event is recursive, much like the “Init” event. During this event, the Viewstate of the page is constructed and serialized into the __VIEWSTATE hidden field.

Info: Again, what exactly goes into the __VIEWSTATE field will be discussed later. |

SaveStateControl (New to ASP.NET 2.0)

State Control is a new feature of ASP.NET 2.0. In ASP.NET 1.1, Viewstate was used to store two kinds of state information for a control:

- Functionality state

- UI state

This resulted in a fairly large __VIEWSTATE field. A very good example is the DataGrid server control. In ASP.NET 1.1, DataGrid uses the Viewstate to store its UI state such as sorting and paging. So, even if you wanted to disable Viewstate on the DataGrid and rebind the data source on each postback, you simply cannot do that if your DataGrid was using sorting or paging. The result was that the DataGrid ended up using Viewstate to store both its bounded data and its UI state such as sorting and paging.

ASP.NET 2.0 solved this problem by partitioning the Viewstate into two:

- The Viewstate we are discussing here

- The Control State

The Control State is used to store the UI state of a control such as the sorting and paging of a DataGrid. In this case, you can safely disable the DataGrid Viewstate (provided, of course, that you rebind the data source at each postback), and the sorting and paging will still work simply because they are saved in the Control State.

The Control State is also serialized and stored in the same __VIEWSTATE hidden field. The Control State cannot be set off.

Render

This is a recursive event much like the “Init” event. During this event, the HTML that is returned to the client requesting the page is generated.

Unload

This is a recursive event much like the “Init” event. This event unloads the page from memory, and releases any used resources.

Viewstate in the “Init” event

The important thing to note in the “Init” event is that Viewstate tracking is not yet enabled. In order to demonstrate this, let us take the following example:

protected override void OnInit(EventArgs e)

(

bool ret;

ret = ViewState.IsItemDirty("item");

ViewSTate["item"] = "1";

ret = ViewState.IsItemDirty("item");returns false

base.OnInit(e);

}

Note that in the above example, the item is still not marked as “Dirty” even after it is being set. This is due to the fact that at this stage, the “TrackViewState()” method is not called yet. It will be called in the “InitComplete” event.

Info: You can force the tracking of Viewstate at any stage that you want. For example, you can call the “Page.TrackViewState()” method at the start of the “Init” event and thus enabling tracking. In this case, the “Init” event will behave exactly like the “InitComplete” event, to be discussed next. |

Viewstate in the “InitComplete” event

In the “InitComplete” event, the Viewstate tracking is enabled. If we take the same example:

protected override void OnInitComplete(EventArgs e)

(

bool ret;

ret = ViewState.IsItemDirty("item");

ViewSTate["item"] = "1";

ret = ViewState.IsItemDirty("item");

base.OnInitComplete(e);

}

This time, note that first, the item is not marked as “Dirty”. However, once it is set, then it is marked as “Dirty”. This is due to the fact that at the start of this event, the “TrackViewState()” method is called.

Viewstate in the “LoadViewState”and “SaveViewState” events

To better understand the role of Viewstate in these events, let us take an example. Say that you have a simple ASPX page that consists of the following:

- A

Label server control with its “Text” property set to “statictext”

- A

Button server control just to postback the page

- The “

Load” event of the page has a statement that sets the “Text” property of the Label control to “dynamictext”. This statement is wrapped inside a “!IsPostback” condition

When the page first loads, the following will happen:

- During the “

Load” event, the “dynamictext” value will be assigned to the “Text” property of the Label

- Later in the life cycle, the “

SaveViewSatte” event is fired, and it stores the new assigned value “dynamictext” in the __VIEWSTATE serialized field (in the next sections, you will see how tracking came into play here)

Now, when you click the Button control, the following will happen:

- The “

LoadViewState” event is fired. The __VIEWSTATE value saved in the previous page visit is loaded. The “dynamictext” value is extracted and assigned back to the “Text” property of the Label.

- The “

Load” event is fired, but nothing happens there because the code is wrapped inside a “!IsPostback” condition.

See how that because of the Viewstate, the “dynamictext” value is persisted across page postback. Without Viewstate and with the “!IsPostback” condition inside the “Load” event, the value “dynamictext” would have been lost after the postback.

OK, so by now, you should have a solid understanding about the page life cycle, the Viewstate, and the role of the Viewstate in the page life cycle. However, we are yet to discuss the cases that tests whether you are an advanced Viewstate user or not. In the next walkthroughs, you shall tackle most of these cases. By the end of this section, you can safely call yourself an advanced Viewstate user.

Walkthrough 1: Viewstate of an empty or Viewstate-disabled page

So, let us start by a very simple question. Will you have a value stored in the __VIEWSTATE field if you have a blank ASP.NET page or a page with Viewstate completely disabled? The answer is yes. As a test, create a blank ASP.NET page and run it. Open the View Source page and note the __VIEWSTATE field. You will notice that it contains a small serialized value. The reason is that the page itself saves 20 or so bytes of information into the __VIEWSTATE field, which it uses to distribute postback data and Viewstate values to the correct controls upon postback. So, even for a blank page or a page with disabled Viewstate, you will see a few remaining bytes in the __VIEWSTATE field.

Walkthrough 2: What is stored in the Viewstate?

As mentioned previously, the data stored in the __VIEWSTATE field consists of the following:

- Data stored by developers using the

Viewstate[“”] indexer

- Programmatic change to the Control State

While the former is pretty much clear, the latter is to be explained thoroughly.

OK, so let us assume that you have a web page with only a Label control on it. Now, let us say that at design time, you set the “Text” property of the Label to “statictext”. Now, load the page and open the View Source page. You will see the __VIEWSTATE field. Do you think “statictext” is saved there? The answer is, for sure, not. Recall from our discussion about generating the compiled class of the page, that static properties of controls are assigned at the generated class? So, when the page is requested, the values stored in the generated class are displayed. As such, static properties that are set at design time are never stored in the __VIEWSTATE field. However, they are stored in the generated compiled class, and thus they show up when rendering the page.

Now, let us say that you did some changes to your page such that it consists of the following:

- A

Label control with the value “statictext” assigned to its “Text” property

- A

Button control to postback the page

- Inside the “

Page_Load” event handler of the page, add code to change the value of the Label’s “Text” property to “dynamictext”. Wrap this code inside a “!IsPostback” condition.

Load the page and open the View Source page. This time, you will notice that the __VIEWSTATE field is larger. This is because at runtime, you changed the value of the “Text” property. And, since you have done this inside the “Load” event, where, at this time, tracking of Viewstate is enabled (remember, tracking is enabled in the “InitComplete” event), the “Text” property is marked as “Dirty”, and thus the “SaveViewstate” event stores its new value in the __VIEWSTATE field. Interesting!!

As a proof that the “dynamictext” value is stored in the __VIEWSTATE field (apart from the fact that it is larger), click the Button control causing a postback. You will find that the “dynamictext” value is retained in the Label even though the code in the “Load” event is wrapped inside the “!IsPostback” condition. This is due to the fact that upon postback, the “LoadViewstate” event extracted the value “dynamictext” which was saved by the “SaveViewState” event during the previous page visit and then assigned it back to the Label’s “Text” property.

Let us now go one step further. Repeat the exact same scenario, with one exception: instead of adding the code that will change the value of the “Text” property at the “Page_Load” event handler, override the “OnPreInit” event handler and add the code there. Now, first load the page, and you will see the new text displayed in the Label. But, do you think this time it is stored in the __VIEWSTATE field? The answer is no. The reason is that during the “PreInit” event, Viewstate tracking is not yet enabled, so the change done to the “Text” property is not tracked and thus not saved during the “SaveViewState” event. As a proof, click the Button causing a postback. You will see that the value displayed inside the Label is the design time value “statictext”.

Let us even go one step further. If you have been following this long article carefully, you will recall that during the “Init” event, tracking of Viewstate is not yet enabled. You have even seen an example in the section Viewstate in the “Init” event of how an item keeps being not dirty even after it is being set. Now, going back to our current example, you will most probably be tempted to consider that if we add the code that changes the value of the “Text” property inside the “OnInit” event handler, you will get the same result as when you put it inside the “OnPreInit” event handler; after all, tracking of Viewstate is not enabled yet during either event. Well, if you think so, then you are mistaken. Reason: if you have been following this article carefully, you will recall that the “InitComplete” event (where tracking of Viewstate is enabled) is not a recursive event; it is called only for the page itself, but not for its child controls. This means that, for the child controls, there is no “InitComplete” event; so, where does the tracking of Viewstate start? The answer is at the start of the “Init” event. So, this means that for the page itself, tracking of Viewstate is enabled at the “InitComplete” event; that is why during the “OnInit” event handler, the item was still marked as not being “Dirty” even after modification. However, for child controls, there is no “InitComplete” event, so the Viewstate tracking is enabled as early as the “Init” event. And, since – again as was explained earlier – the “Init” event is called recursively for the page and its controls in a bottom to up manner, by the time the “Init” event of the page itself is fired, the “Init” event of the child controls is already being fired, and thus Viewstate tracking for child controls is on by that time. As such, adding the code that changes the value of the “Text” property inside the “OnInit” event handler will have the same effect as putting it inside the “Page_Load” event handler.

Walkthorugh 3: What is the larger Viewstate?

Consider the following example: you have two ASP.NET pages: page1.aspx and page2.aspx. Both pages contain only a single Label control. However, in page1, the Label is declared at design time with its “Text” property set to a small string (say 10 characters); in page2, the Label is declared at design time with its “Text” property set to a lengthy string (say 1000 characters). Now, load both pages at the same time, and examine the View Source for both pages. Compare the two __VIEWSTATE fields, what do you find? You will find that both fields are of the same size even though one Label has its “Text” property storing 10 characters while the other has its “Text” property storing 1000 characters. If you have read walkthroughs 1 and 2, you will for sure know the reason: design time property values are not stored in the Viewstate. The __VIEWSTATE value for both pages is simply the bytes emitted by the page itself.

Walkthrough 4: Complete page life cycle scenario

In this walkthrough, we will go through each of the relevant page life cycle events and see what role Viewstate has in each of these events. In this examplem, we have as ASP.NET page with the following characteristics:

- It contains a single

Label control (lbl) with its “Text” property set to “statictext”

- It contains a

Button control (btnA) with code in its event handler that sets the “Text” property of “lbl” to “dynamictext”

- It contains a

Button control (btnB) whose purpose is to cause a page postback

Now, let us examine what will happen during the page life cycle.

- The page is first loaded

- The compiled class of the page is generated and “statictext” is assigned to “

lbl.Text”

- Tracking for Viewstate is enabled in the “

InitComplete” event

- “

LoadViewState” is not fired because there is no postback

- “

SaveViewstate” is fired, but nothing happens because no change of state is recorded

- The page is rendered with the value “statictext” inside “

lbl”

btnA is clicked

- The previously generated compiled class is handed the request; “

lbl.Text” is set to “statictext”

- Tracking for Viewstate is enabled

- “

LoadViewState” is fired, but nothing happens because no change of state was recorded in the previous page visit

- “

RaisePostbackEvent” event is executed and “btnA” click event handler is fired; “lbl.Text” is set to “dynamictext”; since tracking is enabled at this stage, this item is tracked (marked as “Dirty”).

- “

SaveViewState” is fired; “dynamictext” is serialized and stored in the __VIEWSTATE field

- The page is rendered with the value “dynamictext” inside “

lbl”

btnB is clicked

- The previously generated compiled class is handed the request; “lbl.Text” is set to “statictext”

- Tracking for Viewstate is enabled

- “

LoadViewState” is fired; since a change of state was recorded from the previous page visit, __VIEWSTATE is loaded and the value “dynamictext” is extracted; this value is then assigned to “lbl”

- “

RaisePostbackEvent” event is executed; nothing happens here because “btnB” has no event handler for its “Click” event

- “

SaveViewState” is fired, but nothing happens because no change of state is recorded

- The page is rendered with the value “dynamictext” inside “

lbl”

Walkthrough 5: Reducing Viewstate size – Disabling Viewstate

Disabling Viewstate would obviously reduce Viewstate size; but, it surely kills the functionality along the way. So, a little more planning is required…

Consider the case where you have a page with a drop down list that should display the countries of the world. On the “Page_Load” event handler, you bind the drop down list to a data source that contains the countries of the world; the code that does the binding is wrapped inside a “!IsPostback” condition. Finally, on the page, you have a button that when clicked should read the selected country from the drop down list. With the setup described above, you will end up with a large __VIEWSTATE field. This is due to the fact that data bound controls (like the drop down list) store their state inside the Viewstate. You want to reduce Viewstate; what options do you have?

- Option 1: Simply disable the Viewstate on the drop down list

- Option 2: Disable the Viewstate on the drop down list, and remove the “

!IsPostback” condition

- Option 3: Disable the Viewstate on the drop down list, and move the binding code without the “

!IsPostback” condition to the “OnInit” or “OnPreInit” event handlers

If you implement Option 1, you will reduce the Viewstate alright, but with it, you will also lose the list of countries on the first postback of the page. When the page first loads, the code in the “Page_Load” event handler is executed and the list of countries is bound to the list. However, because Viewstate is disabled on the list, this change of state is not saved during the “SaveViewState” event. When the button on the page is clicked causing a postback, since the binding code is wrapped inside a “!IsPostback” condition, the “LoadViewState” event has nothing saved from the previous page visit and the drop down list is empty. If you implement Option 2, you will reduce the Viewstate size and you will not lose the list of countries on postback. However, another problem arises: because the binding code is now executed at each “Page_Load”, the postback data is lost upon postback, and every time, the first item of the list will be selected. This is true because in the page life cycle, the “LoadPostbackdata” event occurs before the “Load” event. Option 3 is the correct option. In this option, you have done the following:

- Disabled Viewstate on the drop down list

- Removed the “

!IsPostback” condition from the binding code

- Moved the binding code to the “

OnInit” event handler (or the “OnPreInit” event handler)

Since the “Init” event occurs before the “LoadPostbackdata” in the page life cycle, the postback data is preserved upon postbacks, and the selected item from the list is correctly preserved.

Now, remember that in Option 3, you have successfully reduced the Viewstate size and kept the functionality working; but, this actually comes at the cost of rebinding the drop down list at each postback. The performance hit of revisiting the data source at each postback is nothing when compared with the performance boost gained from saving a huge amount of bytes being rendered at the client’s __VIEWSTATE field. This is especially true with the fact that most clients are connected to the Internet via low speed dial up connections.

Walkthrough 6: Viewstate and Dynamic Controls

The first fact that you should know about dynamic controls is that they should be added to the page at each and every page execution. Never wrap the code that initializes and adds the dynamic control to the page inside a “!IsPostback” condition. The reason is that since the control is dynamic, it is not included in the compiled class generated for the page. So, the control should be added at every page execution for it to be available in the final control tree. The second fact is that dynamic controls play “catch-up” with the page life cycle once they are added. Say, you did the following:

Label lbl = new Label();

Page.Controls.Add(lbl);

Once the control is added to the “Controls” collection, it plays “catch-up” with the page life cycle, and all the events that it missed are fired. This leads to a very important conclusion: you can add dynamic controls at any time during the page life cycle until the “PreRender” event. Even when you add the dynamic control in the “PreRender” event, once the control is added to the “Controls” collection, the “Init”, “LoadViewState”, “LoadPostbackdata”, “Load”, and “SaveViewstate” are fired for this control. This is called “catch-up”. Note though that it is recommended that you add your dynamic controls during the “PreInit” or “Init” events. This is because it is best to add controls to the control tree before tracking of the Viewstate of other controls is enabled…

Finally, what is the best practice for adding dynamic controls regarding Viewstate? Let us say that you want to add a Label at runtime and assign a value to its “Text” property. What is the best practice to do so? If you are thinking the below, then you are mistaken:

Label lbl = new Label();

Page.Controls.Add(lbl);

lbl.Text = "bad idea";

You are mistaken because using the above technique you are actually storing the value of the “Text” property in the Vewstate. Why? Because, recall that once a dynamic control is added to the “Controls” collection, a “catch-up” happens and the tracking for the Viewstate starts. So, setting the value of the “Text” property will cause the value to be stored in the Viewstate.

However, if you do the below, then you are thinking the right way, because you are setting the “Text” property before adding the control to the “Controls” collection. In this case, the value of the “Text” property is added with the control to the control tree and not persisted in Viewstate.

Label lbl = new Label();

lbl.Text = "good idea";

Page.Controls.Add(lbl);

Summary

This article explained the page life cycle and Viewstate in detail. If you are new to either of the topics, it is advised that you read this article more than once to fully grasp the idea.