Writing code for multiple platforms can be a lot of work. It can be even more work to have to completely rewrite it for each one, too. What if you wrote an application in C++, but wanted it to be displayed in the browser somehow? Well now, with a tool called Emscripten, that’s possible.

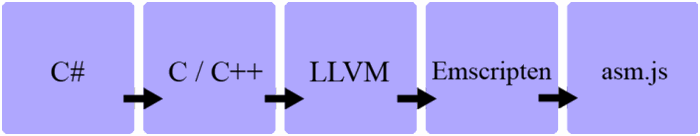

Emscripten is an LLVM based project that compiles C and C++ into highly performant JavaScript in the asm.js format. In short: near native speeds, using C and C++, inside of the browser. Even better, Emscripten converts OpenGL, a desktop graphics API, into WebGL, which is the web variant of that API.

I previously wrote a blog post illustrating what Emscripten is, and how it works in relation to some of my favorite game development tools: Unreal Engine 4 and Unity. Therefore, I won’t go into great detail about how it works here, but instead wanted to focus on creating your own web project which takes advantage of Emscripten, so that you can take C / C++ code and get it running inside of the browser.

Platforms

I’m doing this on Windows 10, but the process is the same for the Unix based platforms, OS X and Linux. The only real change you’ll need to make at this point is in the way you enter your code into the command line / terminal. For Windows, I simply write emcc. For Unix based environments, you must prefix your calls with ./ , so your command would read: ./emcc

The installation process

I had initially considered not writing this tutorial, but when I ran into so many issues with the installer, I thought it would be helpful to others. I looked at how Epic recommended it for exporting projects from UE4, and they suggested to use the SDK Web Installer. This led me down a rabbit hole. I was hoping that the installation process was going to be smooth, but I spent nearly two days trying to get Emscripten working correctly on my machine before having any success. The team has fantastic getting started instructions on the site, but if you pick the wrong installer, you may be in for some trouble.

My first issue was that I chose to go with the Web Installer. This is not the installer you are looking for. Instead, use the SDK Offline installer, and you’ll have smooth sailing and it should only take you a few minutes.

There are a number of bugs with the Web Installer, particularly around the various versions of Visual Studio that you have installed. This is a known issue, but it is being corrected. I believe it has to do with the parallel optimization that Emscripten is doing behind the scenes, and I found that the Cmake was pointing towards the latest version of Visual Studio (2015 community) that I had installed, and not VS 2010, which is what Emscripten was requiring.

You can use Emscripten from Visual Studio, but I found it easier just to perform my builds from the Emscripten CLI. If you did want to use Visual Studio, the instructions can be found here, although only VS 2010 and 2013 are supported at the moment.

"The Emscripten SDK provides the whole Emscripten toolchain (Clang, Python, Node.js and Visual Studio integration) in a single easy-to-install package, with integrated support for updating to newer SDKs as they are released."

–Emscripten Getting Started Guide

Getting Started

Run the Emscripten Command Prompt to get started. I generally hit win + ems and it appears.

You’ll be greeted with the CLI, and will begin at the location where you installed Emscripten.

Navigate to your emsdk root directory. I do this by changing directories to emscripten\tag-1.34.1, because you can see that the path to emscripten is set in the image above as:

EMSCRIPTEN = C:\Program Files\Emscripten\emscripten\tag-1.341

Tip: At any point you can enter ‘explorer .’ into the CLI to open the explorer folder and better visualize what you’re looking at. For folders which have dozens of items, this can often be easier than typing ‘ls’ to list everything in the directory.

Running ‘emcc -v’ will be your sanity check to verify that everything is working correctly in the version you are running. You should see something like:

Now that you can compile your C / C++ work to JavaScript, let’s run the first example, straight from the Emscripten docs. Let’s take hello_world.c and convert it to JavaScript. The C code looks like:

#include<stdio.h>

int main() {

printf("hello, world!\n");

return 0;

}

We are going to be running this out of our tests folder, which is one level further down the chain. To build the code, enter:

emcc tests/hello_world.c

If it all went well, your CLI should pause for a moment, then return to the same location. What’s going on here? Well the compiler wasn’t very verbose about giving us any sort of feedback, so let’s add that now, to get a better understanding of what’s happening behind the scenes.

We’ll add the ‘-v‘ argument to our command, to make the compiler spit out more verbose information.

emcc tests/hello_world.c -v

That’s more like it:

All this did was compile our application to C, and create an a.out.js file in our current directory. If you prefer to use C++, you could use ‘em++’ instead of ‘emcc‘.

This a.out.js is what is key here, because it contains your JavaScript code based on the asm.js specification. If we execute this with node, you will see ‘hello, world‘ appear in the CLI. Enter this command:

node a.out.js

That’s great, but I want to see something in my browser.

Generating HTML

First check your web platform status for browsers that support asm.js. We can actually use Emscripten to generate several different types of extensions with the –o argument. From the docs:

-o <target>

The target file name extension defines the output type to be generated:

<name> .js : JavaScript.

<name> .html : HTML + separate JavaScript file (<name>.js). Having the separate JavaScript file improves page load time.

<name> .bc : LLVM bitcode (default).

<name> .o : LLVM bitcode (same as .bc).

In this case, we want HTML so that we can view it in the browser. Enter this command to specify and HTML document:

Emcc tests/hello_world./c -o hello.html

We are telling Emscripten to use the C compiler to look into the tests folder for the file hello_world.c and then output it ashello.html. Inside of your C:\Program Files \Emscripten\emscripten\tag-1.34.1 folder you should see hello.html.

Open that with your browser, and you can see it as a web page:

But let’s step it up a notch. I want to read from a file and serve some content.

Reading from a file

Because the browser runs JavaScript within a sandboxed environment, we don’t have direct access to the local file system. To work around this, a simulated file system is created by Emscripten so that we can use the libc stdio API to access the compiled C/C++ code. The catch is that the virtual file system requires these files to be embedded or pre-loaded.

Let’s move to the hello_world_file.cpp as our final part of the tutorial and read a file, as this will cover several parts I wanted to discuss, including how to serve the content.

The code for the file looks like:

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

FILE *file = fopen("tests/hello_world_file.txt", "rb");

if (!file) {

printf("cannot open file\n");

return 1;

}

while (!feof(file)) {

char c = fgetc(file);

if (c != EOF) {

putchar(c);

}

}

fclose (file);

return 0;

}

If you have a web background and aren’t used to working with strongly typed languages, you’re probably thinking "What does feof mean?" this threw me into a loop as well, but this Stack Overflow question cleared up quite a bit of confusion for me:

"Now we get to EOF. EOF is the response you get from an attempted I/O operation. It means that you were trying to read or write something, but when doing so you failed to read or write any data, and instead the end of the input or output was encountered. This is true for essentially all the I/O APIs, whether it be the C standard library, C++ iostreams, or other libraries. As long as the I/O operations succeed, you simply cannot know whether further, future operations will succeed. You must always first try the operation and then respond to success or failure."

This is going to attempt to read from a file located at tests/hello_world_file.txt. To do that, we need to run this command:

Emcc tests/hello_world_file.cpp -o hello.html –preload-file tests/hello_world_file.txt

Now try opening that same hello.html file again and see what happens.

In FireFox, all is fine:

But in Chrome and Edge, we don’t have as much luck.

This is because those browsers do not support file:// XHR requets, so local files with preloaded data can’t be loaded. We need to spin up a webserver. We already have python installed, as it is part of the emscriten package, so let’s spin up a simple server from our current directory and try this again.

python -m SimpleHTTPServer 8080

Now in Edge or Chrome, let’s navigate to this file again:

http://localhost:8080/hello.html

And there we go! Serving HTML in the browser, from what was previously just C++.

Connecting C++ and JavaScript

I know what you’re thinking. "This is great, but if there isn’t any sort of interoperability between my C++ and JavaScript, then this isn’t very useful." Fortunately, there is!

There are several ways:

- Call compiled C functions from normal JavaScript:

- Call compiled C++ classes from JavaScript using bindings created with:

- Call JavaScript functions from C/C++:

It’s out of the scope of this tutorial, but I will cover it in a future one. In the meantime, check out the Emscripten docs on the topic.

Not without its limitations

There are several areas where Emscripten is still limited. For example, Code which is multi-threaded cannot be used, as JavaScript is single threaded. The best workaround I could conceive of would be one where you could somehow split this code into web workers, which is JavaScript’s way of simulating multithreading.

There are also bits of code which are known to compile, but run with performance issues. Notably, 64bit int variables. Mathematical operations are slow because they are emulated, but the inclusion of SIMD (Single Instruction Multiple Data) should help with this in the near future as browsers adopt it.

This page on portability guidelines can offer more info.

Following up

I didn’t want to dive too deep with this today, but in my next tutorial for the series, I’d like to cover some more complicated examples, which take advantage of SDLib, as well as a middleware tool such as Unreal Engine 4 or Unity, so that we can see how asm.js really performs in the browser.

More hands-on with Web Development

This article is part of the web development series from Microsoft tech evangelists and engineers on practical JavaScript learning, open source projects, and interoperability best practices including Microsoft Edge browser and the new EdgeHTML rendering engine.

We encourage you to test across browsers and devices including Microsoft Edge – the default browser for Windows 10 – with free tools on dev.microsoftedge.com:

More in-depth learning from our engineers and evangelists:

Our community open source projects:

More free tools and back-end web dev stuff: