“I have created my code, split out some functionality and written the tests. But the mocks have become a real mess, and much more work than I had thought it would be. Can you help me, Sensei?”

“Of course. Show me your code, grasshopper”

The code is a validator class with different validation methods. The public functions in this class would perform the validations, and in turn call some private methods to retrieve data from the database.

“How can I test these private methods, sensei?”

“Usually, if you have private methods that need to be tested, that’s a code smell already. It isn’t always bad, but it could indicate more problems. Using the PrivateObject class can help you with this.”

The validators would first call some of the private methods, then perform some trivial additional tests and then return the validation result as a Boolean. So to test the actual validation methods, the private methods were put as public (smell) and then stubbed. So something was going wrong here. But my young apprentice came with a very good answer:

“But sensei, if stubbing out methods in a class to test other methods in the same class smells so hard, wouldn’t it be a good idea then to move these methods into a separate class?”

Now we’re talking! The Validation class was actually doing 2 separate things. It was:

- validating input

- retrieving data from the database

This clearly violates the “Separation of Concerns” principle. A class should do one thing. So let’s pseudo-code our example:

public class Validator

{

public bool CanDeleteClient(Client x)

{

bool hasOrders = HasClientOrders(x);

bool hasOpenInvoices = HasOpenInvoices(x);

return !hasOrders && !hasOpenInvoices;

}

public bool CanUpdateClient(Client x)

{

bool hasOpenInvoices = HasOpenInvoices(x);

return !hasOpenInvoices;

}

public bool HasClientOrders(Client x)

{

}

public bool HasOpenInvoices(Client x)

{

}

}

In the tests, the HasClientOrders and HasOpenInvoices functions were stubbed so no data access would be required. They were actually put public to make it possible to test them.

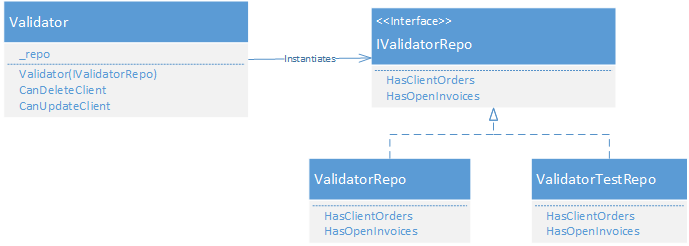

So, splitting this code out in 2 classes makes testing a lot easier. Here is a drawing of what we want to achieve:

Show Me the Code

interface IValidatorRepo

{

bool HasClientOrders(Client);

bool HasOpenInvoices(Client);

}

public class ValidatorRepo : IValidatorRepo

{

public bool HasClientOrders(Client) { … }

public bool HasOpenInvoices(Client) { … }

}

public class Validator

{

IValidatorRepo _repo;

public Validator()

{

_repo = new ValidatorRepo();

}

public Validator(IValidatorRepo repo)

{

_repo = repo;

}

public bool CanDeleteClient(Client x)

{

bool hasOrders = _repo.HasClientOrders(x);

bool hasOpenInvoices = _repo.HasOpenInvoices(x);

return !hasOrders && !hasOpenInvoices;

}

public bool CanUpdateClient(Client x)

{

bool hasOpenInvoices = _repo.HasOpenInvoices(x);

return !hasOpenInvoices;

}

}

What have we achieved by this? We now have 2 classes and 1 interface instead of just 1 class. There seems to be more code, and it looks more complex…

But the class Validator violated the “Separation of Concerns” principle. Instead of only validating, it was also accessing the data. And we have fixed this now. The ValidatorRepo class does the data access, and it is a very simple class. The Validator class just checks if a client has orders or open invoices, but it doesn’t care how this is done.

Notice that there are 2 constructors: The default constructor will instantiate the actual ValidatorRepo, and the second version takes the IValidatorRepo interface. So now in our test program, we can create a class that just returns true / false in any combination that we like, and then instantiates the Validator with this.

In the Validator, we then just call the methods on the interface, again “not caring” how they are implemented. So we can test the Validator implementation without needing a database. We don’t have to stub functions in our function under test, so the air is clean again (no more smells).

“Thank you sensei. But it seems that this is something very useful, so I would think that somebody would have thought about it already?”

“Yes, this principle is called Dependency Injection, and it is one of the ways to achieve testable classes, by implementing Separation of Concerns.”