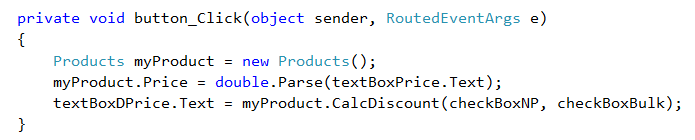

One goal to keep in mind as you write software is to write software that is easy to maintain and enhance in the future. We can do this by organizing code so that things that might change will be easier to change. Consider this example:

In the code above, User Interface (UI) code is mixed together with the business object code. We should try not to pass details about how the UI implements a feature unless the business object really needs to know. In this example, the Products business object really only needs to know three pieces of information from the UI:

- The Price

- Should a discount be calculated because this is for a nonprofit agency? (yes or no)

- Should a discount be calculated because this is a bulk purchase? (yes or no)

If we change the code to pass boolean values to the Products business object instead of the checkboxes, we gain the following benefits:

- The UI can easily be changed in the future to use something other than checkboxes, and this change will not require also changing code in the

Products business object. - We increase our potential to use the

Products business object with different types of user interfaces. This business object may currently expect a C# WPF checkbox control, which means the business object would not work if someone had a C# Windows checkbox control, or perhaps a C# Silverlight checkbox control. But if the Products business object accepted a boolean, which is a datatype common to more platforms, the business object will more likely work with different user interfaces. - Unit tests that we write won’t need to reference the specific UI components needed for building the user interface.

A more common way that developers often entwine UI code with business object code is shown below. This example is the opposite of the case above. Here logic that could, and should, reside in the business object is performed in the UI.

The reason we don’t like this code is that logic to calculate the discounted price should be moved from the UI to the Product business object. In doing so, we would gain the following benefits:

- We could reuse the

Product business object in another program without needing to also add logic to the UI of the other program to calculate the discounted price. - If we need to change the calculation for the discounted price, we need to make the change in only one place and every program using that business object automatically is affected.

- We can easily write a unit test on the

Product business object to make sure that the code calculating our discounted price works correctly.

A better way to write the code from both examples above so that the UI and business logic is not entwined is shown below. I will admit that this is not the best example, because it does not use TryParse, nor does it have input checking and error handling, and it could use an interface, but those topics are not the point of this article, which is to encourage you to separate the UI logic from the business logic in your applications.

It is not bad sometimes to write code that entangles UI code and business logic, knowing that you will refactor the code to move the logic to the correct place before you consider the feature complete. It is often helpful to have all of the code in one big method until you have it correct, then you can improve the code by refactoring it.

As with any of Robert’s Rules of Coding, you don’t need to adhere to them all of the time and there are cases where it is better not to. But most programmers should follow the rules most of the time. I hope you agree.

Go to Robert’s Rules of Coders for more.