Strings and the Common Language Runtime (CLR) have a special relationship, but it’s a bit different (and way less political) than the UK <-> US special relationship that is often talked about.

This relationship means that Strings can do things that aren’t possible in the C# code that you and I can write and they also get a helping hand from the runtime to achieve maximum performance, which makes sense when you consider how ubiquitous they are in .NET applications.

String Layout in Memory

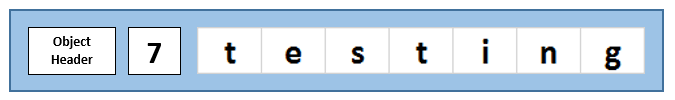

Firstly strings differ from any other data type in the CLR (other than arrays) in that their size isn’t fixed. Normally, the .NET GC knows the size of an object when it’s being allocated, because it’s based on the size of the fields/properties within the object and they don’t change. However in .NET, a string object doesn’t contain a pointer to the actual string data, which is then stored elsewhere on the heap. That raw data, the actual bytes that make up the text are contained within the string object itself. That means that the memory representation of a string looks like this:

The benefit is that this gives excellent memory locality and ensures that when the CLR wants to access the raw string data, it doesn’t have to do another pointer lookup. For more information, see the Stack Overflow questions “Where does .NET place the String value?” and Jon Skeet’s excellent post on strings.

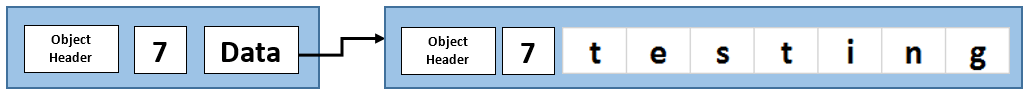

Whereas if you were to implement your own string class, like so:

public class MyString

{

int Length;

byte [] Data;

}

If would look like this in memory:

In this case, the actual string data would be held in the byte [], located elsewhere in memory and would therefore require a pointer reference and lookup to locate it.

This is summarized nicely in the excellent BOTR, in the mscorlib section:

The managed mechanism for calling into native code must also support the special managed calling convention used by String’s constructors, where the constructor allocates the memory used by the object (instead of the typical convention where the constructor is called after the GC allocates memory).

Implemented in Un-managed Code

Despite the String class being a managed C# source file, large parts of it are implemented in un-managed code, that is in C++ or even Assembly. For instance, there are 15 methods in String.cs that have no method body, are marked as extern with [MethodImplAttribute(MethodImplOptions.InternalCall)] applied to them. This indicates that their implementations are provided elsewhere by the runtime. Again, from the mscorlib section of the BOTR (emphasis mine)

We have two techniques for calling into the CLR from managed code. FCall allows you to call directly into the CLR code, and provides a lot of flexibility in terms of manipulating objects, though it is easy to cause GC holes by not tracking object references correctly. QCall allows you to call into the CLR via the P/Invoke, and is much harder to accidentally mis-use than FCall. FCalls are identified in managed code as extern methods with the MethodImplOptions.InternalCall bit set. QCalls are static extern methods that look like regular P/Invokes, but to a library called “QCall”.

Types with a Managed/Unmanaged Duality

A consequence of Strings being implemented in unmanaged and managed code is that they have to be defined in both and those definitions must be kept in sync:

Certain managed types must have a representation available in both managed & native code. You could ask whether the canonical definition of a type is in managed code or native code within the CLR, but the answer doesn’t matter – the key thing is they must both be identical. This will allow the CLR’s native code to access fields within a managed object in a very fast, easy to use manner. There is a more complex way of using essentially the CLR’s equivalent of Reflection over MethodTables & FieldDescs to retrieve field values, but this probably doesn’t perform as well as you’d like, and it isn’t very usable. For commonly used types, it makes sense to declare a data structure in native code & attempt to keep the two in sync.

So in String.cs, we can see:

[NonSerialized]private int m_stringLength;

[NonSerialized]private char m_firstChar;

Which corresponds to the following in object.h.

private:

DWORD m_StringLength;

WCHAR m_Characters[0];

Fast String Allocations

In a typical .NET program, one of the most common ways that you would allocate strings dynamically is either via StringBuilder or String.Format (which uses StringBuilder under the hood).

So you may have some code like this:

var builder = new StringBuilder();

...

builder.Append(valueX);

...

builder.Append("Some text")

...

var text = builder.ToString();

or:

var text = string.Format("{0}, {1}", valueX, valueY);

Then, when the StringBuilder ToString() method is called, it internally calls the FastAllocateString on the String class, which is declared like so:

[System.Security.SecurityCritical] [MethodImplAttribute(MethodImplOptions.InternalCall)]

internal extern static String FastAllocateString(int length);

This method is marked as extern and has the [MethodImplAttribute(MethodImplOptions.InternalCall)] attribute applied and as we saw earlier, this implies it will be implemented in un-managed code by the CLR. It turns out that eventually the call stack ends up in a hand-written assembly function, called AllocateStringFastMP_InlineGetThread from JitHelpers_InlineGetThread.asm.

This also shows something else we talked about earlier. The assembly code is actually allocating the memory needed for the string, based on the required length that was passed in by the calling code.

LEAF_ENTRY AllocateStringFastMP_InlineGetThread, _TEXT

mov r9, [g_pStringClass]

cmp ecx, (ASM_LARGE_OBJECT_SIZE - 256)/2

jae OversizedString

mov edx, [r9 + OFFSET__MethodTable__m_BaseSize]

lea edx, [edx + ecx*2 + 7]

and edx, -8

PATCHABLE_INLINE_GETTHREAD r11, AllocateStringFastMP_InlineGetThread__PatchTLSOffset

mov r10, [r11 + OFFSET__Thread__m_alloc_context__alloc_limit]

mov rax, [r11 + OFFSET__Thread__m_alloc_context__alloc_ptr]

add rdx, rax

cmp rdx, r10

ja AllocFailed

mov [r11 + OFFSET__Thread__m_alloc_context__alloc_ptr], rdx

mov [rax], r9

mov [rax + OFFSETOF__StringObject__m_StringLength], ecx

ifdef _DEBUG

call DEBUG_TrialAllocSetAppDomain_NoScratchArea

endif

ret

OversizedString:

AllocFailed:

jmp FramedAllocateString

LEAF_END AllocateStringFastMP_InlineGetThread, _TEXT

There is also a less optimized version called AllocateStringFastMP from JitHelpers_Slow.asm. The reason for the different versions is explained in jinterfacegen.cpp and then at run-time, the decision is made as to which one to use, depending on the state of the Thread-local storage.

EXTERN_C Object* JIT_TrialAllocSFastMP_InlineGetThread(CORINFO_CLASS_HANDLE typeHnd_);

EXTERN_C Object* JIT_BoxFastMP_InlineGetThread (CORINFO_CLASS_HANDLE type, void* unboxedData);

EXTERN_C Object* AllocateStringFastMP_InlineGetThread (CLR_I4 cch);

EXTERN_C Object* JIT_NewArr1OBJ_MP_InlineGetThread (CORINFO_CLASS_HANDLE arrayTypeHnd_, INT_PTR size);

EXTERN_C Object* JIT_NewArr1VC_MP_InlineGetThread (CORINFO_CLASS_HANDLE arrayTypeHnd_, INT_PTR size);

EXTERN_C Object* JIT_TrialAllocSFastMP(CORINFO_CLASS_HANDLE typeHnd_);

EXTERN_C Object* JIT_TrialAllocSFastSP(CORINFO_CLASS_HANDLE typeHnd_);

EXTERN_C Object* JIT_BoxFastMP (CORINFO_CLASS_HANDLE type, void* unboxedData);

EXTERN_C Object* JIT_BoxFastUP (CORINFO_CLASS_HANDLE type, void* unboxedData);

EXTERN_C Object* AllocateStringFastMP (CLR_I4 cch);

EXTERN_C Object* AllocateStringFastUP (CLR_I4 cch);

Optimised String Length

The final example of the “special relationship” is shown by how the string Length property is optimized by the run-time. Finding the length of a string is a very common operation and because .NET strings are immutable should also be very quick, because the value can be calculated once and then cached.

As we can see in the comment from String.cs, the CLR ensures that this is true by implementing it in such a way that the JIT can optimize for it:

This code is implemented in stringnative.cpp, which in turn calls GetStringLength:

FCIMPL1(INT32, COMString::Length, StringObject* str) {

FCALL_CONTRACT;

FC_GC_POLL_NOT_NEEDED();

if (str == NULL)

FCThrow(kNullReferenceException);

FCUnique(0x11);

return str->GetStringLength();

}

FCIMPLEND

Which is a simple method call that the JIT can inline:

DWORD GetStringLength() { LIMITED_METHOD_DAC_CONTRACT; return( m_StringLength );}

Why Have A Special Relationship?

In one word performance, strings are widely used in .NET programs and therefore need to be as optimized, space efficient and cache-friendly as possible. That’s why they have gone to great lengths, including implementing methods in assembly and ensuring that the JIT can optimize code as much as possible.

Interestingly enough, one of the .NET developers recently made a comment about this on a GitHub issue, in response to a query asking why more string functions weren’t implemented in managed code, they said:

We have looked into this in the past and moved everything that could be moved without significant perf loss. Moving more depends on having pretty good managed optimizations for all coreclr architectures. This makes sense to consider only once RyuJIT or better codegen is available for all architectures that coreclr runs on (x86, x64, arm, arm64).

Discuss this post on Hacker News or /r/programming

The post Strings and the CLR - a Special Relationship appeared first on my blog Performance is a Feature!

CodeProject