In this article, I'm going to demonstrate a few tips and tricks which can make your life easier when you are building or maintaining Dockerfiles.

The Need for a Build Pipeline

Do we really need any kind of continuous integration or build pipeline for Dockerfiles?

There will be cases when the answer is no. However, if the answer to any of the following questions is 'yes', it might be worth considering:

- Do you want others to be able to contribute to the Dockerfile, perhaps changing the image over time?

- Are there specific functionalities in your Dockerfiles which could break if altered?

- Do you expect to need to release updates to your Dockerfile?

Essentially, if we are looking at providing some kind of automated quality assurance and automation around building and releasing, then a build pipeline is not a bad idea.

A Simple Build Pipeline

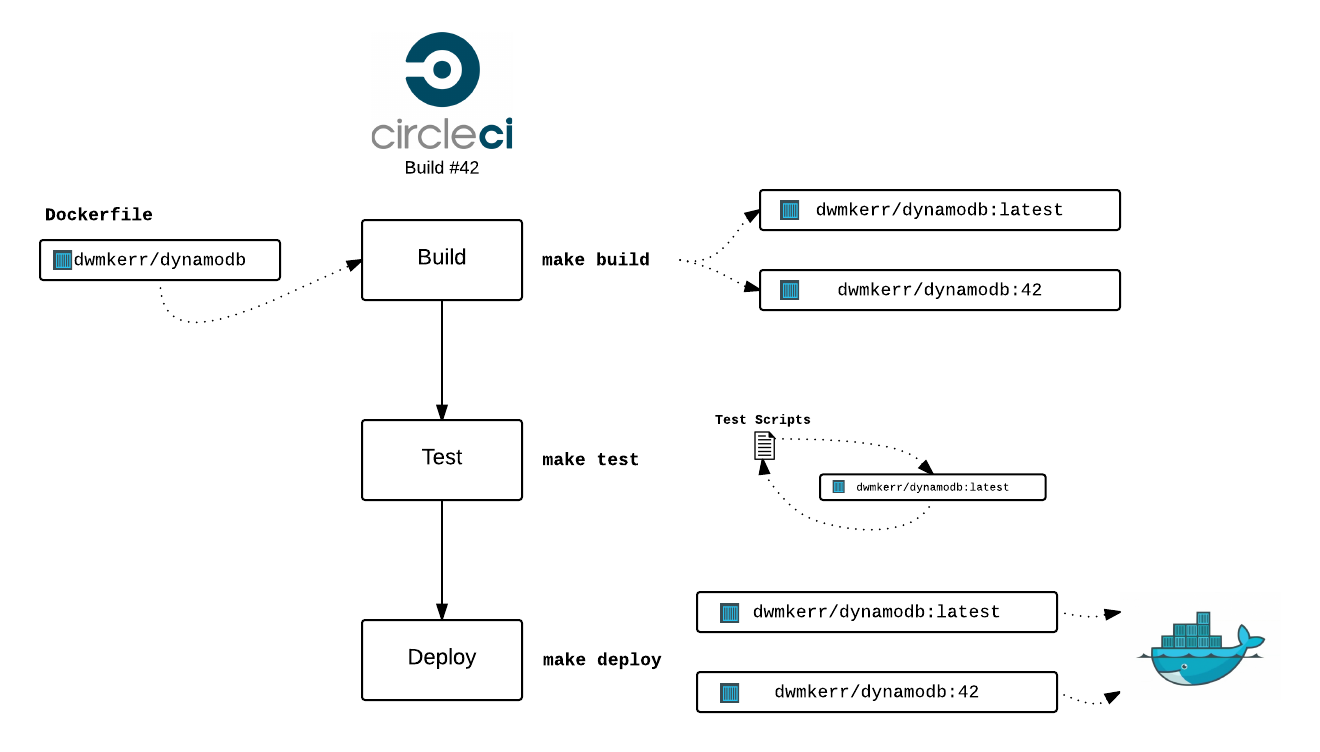

Here's what a simple build pipeline could look like. This example is for a Docker Image I just created for local DynamoDB development - dwmkerr/dynamodb:

Let's dissect what we've got here.

The Dockerfile

This is the main 'code' of the project if you like. The Dockerfile is the recipe for the image we create.

The Continuous Integration Service

In this case, I am using CircleCI, however the approach described would work fine with most CI systems (such as Jenkins, TravisCI and TeamCity). There is an option to use the Docker Hub Automated Builds, but I've found this doesn't give the flexibility I need (see Why not Docker Hub Automated Builds).

Essentially the CI service needs to offer the option to have three distinct steps in the pipeline, each of which must pass for the process to proceed:

- Build

- Test

- Deploy

The Build

We can build with tools, script files, whatever. At the moment, I am leaning towards makefiles. Normally, I only need a few lines of shell script to do a build - anything more complex and the makefile can call a shell script. See also Why Makefiles?

Here's what it might look like:

build:

docker build -t dwmkerr/dynamodb:latest .

ifndef BUILD_NUM

$(warning No build number is defined, skipping build number tag.)

else

docker build -t dwmkerr/dynamodb:$(BUILD_NUM) .

endif

This command just builds the Dockerfile and tags it as dwmkerr/dynamodb:lastest. If a BUILD_NUM variable is present, we also create the tag dwmkerr/dynamodb:BUILD_NUM. This means if we want to deploy to a service such as Amazon ECS, we can push a specific build by referring to the image with that tag.

The Tests

Again, I'm relying on make. I just want to be able to run make test - if zero is returned, I'm happy. If not, the pipeline should stop and I'll check the output. Here's my test command:

test: build

./test/basics.test.sh

./test/ephemeral.test.sh

./test/persistent.test.sh

Not a thing of beauty, but it works. These scripts I'll discuss a little bit later on, in the delightly titled What are these test scripts section.

For CircleCI, this is enough to have the main part of our pipeline. Here's how the circle.yml file looks at this stage:

machine:

services:

- docker

environment:

# Set the build number, used in makefiles.

BUILD_NUM: $CIRCLE_BUILD_NUM

test:

override:

- make test

(Actually, there's a couple of other bits but they're just to make sure circle uses the right version of Docker, see the full circle.yml file here).

The Deployments

Deployments are trivial as all we need to do is push to the Docker Hub. The make deploy command looks-a like this:

deploy:

docker push dwmkerr/dynamodb:latest

ifndef BUILD_NUM

$(warning No build number is defined, skipping push of build number tag.)

else

docker push dwmkerr/dynamodb:$(BUILD_NUM)

endif

We're pushing the latest tag and BUILD_NUM tag if present. To add this to the CircleCI pipeline, we just add the following to circle.yml:

deployment:

master:

branch: master

commands:

- docker login -e $DOCKER_EMAIL -u $DOCKER_USERNAME -p $DOCKER_PASSWORD

- make deploy

If we have a push to master, we log in to Docker (using environment variables I configure in the CircleCI UI) and then run make deploy to push our images.

That's It

That's about it. This is a pretty simple approach, you can see it in action at:

The rest of this post is a bit of a deep dive into some specific areas I found interesting.

Appendix 1: Why Not Docker Hub Automated Builds?

There are automated builds available in the Docker Hub:

I'm not using this feauture at the moment. Here's a brief roundup of what I think are the current pros and cons:

Pros

- You don't have to goof around installing Docker on a CI platform.

- It allows you to update the description of your Docker image automatically, from the GitHub README.md.

- It allows you to associate the image with a specific GitHub repo (rather than just linking from the image description).

- Branch management - allowing tags to be built for specific branches.

Cons

- It doesn't seem to support any kind of configurable gating, such as a running a test command prior to deploying.

- It doesn't seem to support any kind of triggering of downstream processes, such as updating environments, sending notifications or whatever.

The lack of ability to perform tests on the image before deploying it is why I'm currently not using the service.

By doing the testing in a CI system for every pull request and only merging PRs where the tests pass, we could mitigate the risk here. This service is worth watching as I'm sure it will evolve quickly.

Appendix 2: Why Makefiles?

I started coding with a commandline compiler in DOS. When I used my first GUI (Borland Turbo C++), it felt like a huge leap:

Later on, I moved onto Microsoft Visual C++ 4.2:

And you cannot imagine the excitement when I got my boxed edition of Visual Studio .NET:

Wow!

Anyway, I digress. GNU make was invented by Leonardo Da Vinci in 1473 to allow you to build something from the commandline, using a fairly consistent syntax.

It is near ubiquitous on *nix systems. I am increasingly using it as an 'entry point' to builds, as I use variety of languages and platforms. Being able to know that most of the time:

make build

make test

Will build and test something is convenient. Makefiles actually are not that great to work with (see this, this and this). I've found as long as you keep the commands simple, they're OK. For anything really complex, I normally have a scripts/ folder, but call the scripts from the makefile, so that there's still a simple entrypoint.

I'm not entirely sold on makefiles, but they tend to be my default at the moment if I know I'm going to use the commandline for builds (for example, in Java projects, I'll often write a makefile to call Maven or Gradle).

For things like Node.js, where you have commands like npm test or npm run xyz, I still sometimes use makefiles, using npm for day-to-day dev tests (npm start) and make if it's something more complex (e.g. make deploy-sit to deploy to an SIT environment).

Appendix 3: What Are These Test Scripts?

You may have noticed:

test: build

./test/basics.test.sh

./test/ephemeral.test.sh

./test/persistent.test.sh

What's going on here?

My Docker image is just a wrapper around Amazon's Local DynamoDB tool. I don't really need to test that tool. But what I wanted to test was the capabilities which lie at the intersection between 'native' Docker and 'native' DynamoDB.

For example, I know Docker supports volume mapping. I know DynamoDB supports using a data directory, to allow persistent between runs. I want to test I can combine Docker volume mapping and the DynamoDB data directory features. I know Docker images should default to being ephemeral, I want to test this holds true by default for my image.

Testing Docker is a little hard - I want to test that I can run containers, start, stop, check state before and after and so on. This is essentially an integration test, it can be tricky to make it truly isolated and deterministic.

I've given it my best go with these scripts. Here's an example for the 'ephemeral' test, where I'm trying to assert that if I run a container, create a table, stop the container and run a new one, I no longer have the table. Here's the test:

# Bomb if anything fails.

set -e

# Kill any running dynamodb containers.

echo "Cleaning up old containers..."

docker ps -a | grep dwmkerr/dynamodb |

awk '{print $1}' | xargs docker rm -f || true

# Run the container.

echo "Checking we can run the container..."

ID=$(docker run -d -p 8000:8000 dwmkerr/dynamodb)

sleep 2

# Create a table.

aws dynamodb --endpoint-url http://localhost:8000 --region us-east-1 \

create-table \

--table-name Supervillains \

--attribute-definitions AttributeName=name,AttributeType=S \

--key-schema AttributeName=name,KeyType=HASH \

--provisioned-throughput ReadCapacityUnits=1,WriteCapacityUnits=1

# Clean up the container. On CircleCI the FS is BTRFS, so this might fail...

echo "Stopping and restarting..."

docker stop $ID && docker rm $ID || true

ID=$(docker run -d -p 8000:8000 dwmkerr/dynamodb)

sleep 2

# List the tables - there shouldn't be any!

COUNT=$(aws dynamodb --endpoint-url http://localhost:8000 --region us-east-1 \

list-tables \

| jq '.TableNames | length')

if [ $COUNT -ne "0" ]; then

echo "Expected to find no tables, found $COUNT..."

exit 1

fi

It's a bit dirty - it removes containers from the host, changes things and so on. But it works.

I did experiment with running these tests in a container, which has the benefit of giving you a clean host to start with, which you can throw away after each test.

I had to give up after a little while due to time constraints, but will probably revisit this process. The benefits of running these integration tests in a container is that we get a degree of isolation from the host.

If anyone is interested, my attempts so far are on this RFC Pull Request. Feel free to jump in!