Contents

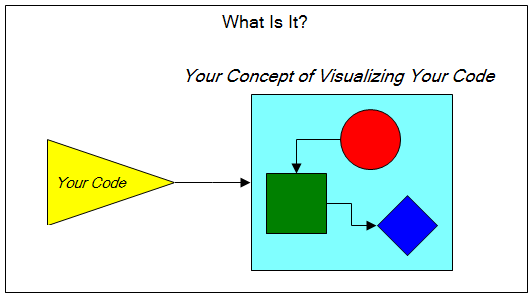

OK, the real project name is FlowSharpCode, but I thought I'd have fun with the title!

First off, this is purely a concept piece. It's intended to either inspire or cause an eye rolling "what a crazy idea" reaction. It's crazy, in my opinion, but in a sense it's crazy because in my limited use cases so far, it works. And because it's so crazy, the majority of this article will not be written, it'll be screenshots of the application in use. The problem with this approach is that it ends up sort of looking like a PowerPoint presentation, which is hard to avoid!

Now you when you build the "app", you have a separate assembly:

Let's take this simple piece of code:

public static void Main()

{

try

{

WebServer ws = new WebServer();

ws.Start("localhost", new int[] {8001});

Console.WriteLine("Press a key to exit the server.");

Console.ReadLine();

}

catch(Exception ex)

{

Console.WriteLine(ex.Message);

Console.ReadLine();

}

}

and make it into a workflow.

Back to pictures...

The first step in the workflow:

The second step in the workflow:

The third step in the workflow:

The last step in the workflow:

Now, that's crazy, cool, a lot of typing (except copy & paste of shapes, which carries along the code, makes it rather painless) and of course has no way of exiting a workflow early. Whatever -- it's a playground, not a rocket ship.

With all the annotations, etc.

Now, I could bore you with making workflows out of the other methods in the webserver assembly, but I'll leave that as an exercise for the reader, haha.

So far what you've seen is really nothing more than the "trick" of using partial classes to separate methods out into discrete files. That's right, the code you write in the editor for a selected shape is compiled as a discrete file -- it's actually saved as a temporary file, compiled, and then deleted. Building an assembly is really nothing more than figuring out which shapes are contained inside the "Assy" shape and compiling those to an assembly rather than an EXE. We'll use a similar technique for defining workflows, but:

- This is where you, as the programmer, are first constrained to use a particular coding pattern,

- and FlowSharpCode actually generates some code for you.

There are a few constraints:

- The workflow name must be [packetname]workflow.dll

- The shape text for each workflow step must be the same as the implementing method name -- I use the shape text rather than parsing the C#. Shiver.

- The auto-generate always creates an

Execute method, which is your entry point to the workflow.

Technically, the purpose of this tool is to not constrain the programmer into a specific coding pattern, and with proper code parsing, type inference, and other tricks, those constraints could potentially be eased at some point.

Just like before:

- Contain the workflow in an "Assy" shape

- Give it a filename (ending with DLL)

- Fix up the references

First off, the code base is a bit of a mess because I've been prototyping these concepts and you should in no way treat this as a useable tool. It's a playground, that's it! Get the code from GitHub here. The demo files are in:

- Article\SimpleServer.fsd - the version of the server and app as a single exe

- Article\SimpleServerAssy.fsd - the version of the server as a separate dll

- Article\SimpleServerWorkflow.fsd - the version of the server implemented as workflows.

- Article\SimpleServerWorkflowAsAssembly.fsd - the version where the workflow is also an assembly.

OK, this is where the part gets serious. :)

First off, this playground is built off of my FlowSharp diagramming tool, so the main thing I'm going to show here is the code for building the exe and dll's, which I want to re-iterate again, is prototype "throw it together" code. Readers may also be interested in that I'm using SharpDevelop's WPF Avalon editor for the C# code, along with Luke Buehler's NRefactory-Completion-Sample for the Intellisense functionality and the ScintillaNET editor for other file types other than C#. The whole architecture is based on my modular approach, which is discussed in my "The Clifton Method" articles. Lastly, the docking manager is provided by DockPanelSuite, originally written by WeiFen Luo and now maintained on GitHub by others.

The IDE

It's fully dockable, but I don't restore your dock settings on startup (yet!)

The Overall Architecture

There's a lot of moving parts because I want a highly modular system for developing applications. This is a baby step, but I might as well start out with modular, right?

There are five core services:

- The WPF Avalon Editor Service, courtesy of SharpDevelop

- The Scintilla Editor Service

- The Docking Form Service

- The FlowSharp Canvas Service

- The FlowSharp Toolbox Service

- The Semantic Processor Service

These are all loaded at runtime. You can read about how:

(Yeah, I like to see my name splattered all over an article.)

I've provided links elsewhere in this article for the outstanding components that I'm using, the docking manager, Intellisense, WPF Avalon editor, and ScintillaNet.

So, the core value added piece is really the code compilation. It's ugly, it's in MenuController2.cs (great place, right?), so don't forget it's prototype code!

The top level method is the toaster. It does it all:

protected void Compile()

{

tempToTextBoxMap.Clear();

List<GraphicElement> compiledAssemblies = new List<GraphicElement>();

bool ok = CompileAssemblies(compiledAssemblies);

if (!ok)

{

DeleteTempFiles();

return;

}

List<string> refs = new List<string>();

List<string> sources = new List<string>();

List<GraphicElement> rootSourceShapes = GetSources();

rootSourceShapes.ForEach(root => GetReferencedAssemblies(root).Where(refassy => refassy is IAssemblyBox).ForEach(refassy => refs.Add(((IAssemblyBox)refassy).Filename)));

IEnumerable<GraphicElement> workflowShapes = canvasController.Elements.Where(el => el is IWorkflowBox);

workflowShapes.ForEach(wf =>

{

string code = GetWorkflowCode(wf);

wf.Json["Code"] = code;

});

rootSourceShapes.Where(root => !String.IsNullOrEmpty(GetCode(root))).ForEach(root =>

{

CreateCodeFile(root, sources, GetCode(root));

});

exeFilename = String.IsNullOrEmpty(filename) ? "temp.exe" : Path.GetFileNameWithoutExtension(filename) + ".exe";

Compile(exeFilename, sources, refs, true);

DeleteTempFiles();

}

Basically, we:

- Compile all assemblies first

- Build the code for the workflows and add them to the source code list

- Compile the code

- Output errors in a message box (yuck)

One nuance I discovered is that in-memory compilation doesn't give you line numbers. Maybe I'm doing something wrong. The workaround is to create temporary files and map those to the shape Text property so I can tell you what shape's code resulted in the error. Like this:

protected void CreateCodeFile(GraphicElement root, List<string> sources, string code)

{

string filename = Path.GetFileNameWithoutExtension(Path.GetTempFileName()) + ".cs";

tempToTextBoxMap[filename] = root.Text;

File.WriteAllText(filename, GetCode(root));

sources.Add(filename);

}

We figure out what shapes are assemblies by looking for shapes that implement IAssemblyBox:

protected bool CompileAssemblies(List<GraphicElement> compiledAssemblies)

{

bool ok = true;

foreach (GraphicElement elAssy in canvasController.Elements.Where(el => el is IAssemblyBox))

{

CompileAssembly(elAssy, compiledAssemblies);

}

return ok;

}

The actual compilation is a recursive process intended to ensure that all referenced assemblies are first compiled:

protected string CompileAssembly(GraphicElement elAssy, List<GraphicElement> compiledAssemblies)

{

string assyFilename = ((IAssemblyBox)elAssy).Filename;

if (!compiledAssemblies.Contains(elAssy))

{

compiledAssemblies.Add(elAssy);

List<GraphicElement> referencedAssemblies = GetReferencedAssemblies(elAssy);

List<string> refs = new List<string>();

foreach (GraphicElement el in referencedAssemblies)

{

string refAssy = CompileAssembly(el, compiledAssemblies);

refs.Add(refAssy);

}

List<string> sources = GetSources(elAssy);

Compile(assyFilename, sources, refs);

}

return assyFilename;

}

Referenced assemblies (given a shape we know is an assembly) is determined again by inspecting any connectors, and in this case, where the arrow is. Don't create connectors pointing the wrong way, or a connector with two arrows, or a connector with no arrows. Remember to chant the mantra "Prototype! Prototype! Prototype!"

protected List<GraphicElement> GetReferencedAssemblies(GraphicElement elAssy)

{

List<GraphicElement> refs = new List<GraphicElement>();

elAssy.Connections.Where(c => ((Connector)c.ToElement).EndCap == AvailableLineCap.Arrow).ForEach(c =>

{

if (((Connector)c.ToElement).EndConnectedShape != elAssy)

{

GraphicElement toAssy = ((Connector)c.ToElement).EndConnectedShape;

refs.Add(toAssy);

}

});

elAssy.Connections.Where(c => ((Connector)c.ToElement).StartCap == AvailableLineCap.Arrow).ForEach(c =>

{

if (((Connector)c.ToElement).StartConnectedShape != elAssy)

{

GraphicElement toAssy = ((Connector)c.ToElement).StartConnectedShape;

refs.Add(toAssy);

}

});

return refs;

}

Root level sources (those that aren't IAssemblyBox or IFileBox) is fun little kludge leveraging the knowledge that even grouped shapes are actually represented as top-level elements in the shape list.

protected bool ContainedIn<T>(GraphicElement child)

{

return canvasController.Elements.Any(el => el is T && el.DisplayRectangle.Contains(child.DisplayRectangle));

}

protected List<GraphicElement> GetSources()

{

List<GraphicElement> sourceList = new List<GraphicElement>();

foreach (GraphicElement srcEl in canvasController.Elements.Where(

srcEl => !ContainedIn<IAssemblyBox>(srcEl) &&

!(srcEl is IFileBox)))

{

sourceList.Add(srcEl);

}

return sourceList;

}

Assembly shapes that "group" other code shapes (they're not really groupboxes) are determined like this, given an assembly box shape (or really any other shape, I use this method for figuring out the code in a workflow "group" as well):

protected List<string> GetSources(GraphicElement elAssy)

{

List<string> sourceList = new List<string>();

foreach (GraphicElement srcEl in canvasController.Elements.

Where(srcEl => elAssy.DisplayRectangle.Contains(srcEl.DisplayRectangle)))

{

string filename = Path.GetFileNameWithoutExtension(Path.GetTempFileName()) + ".cs";

tempToTextBoxMap[filename] = srcEl.Text;

File.WriteAllText(filename, GetCode(srcEl));

sourceList.Add(filename);

}

return sourceList;

}

And the crowning jewel of all this mess is the compilation of the source code (more mess, more hard-coded stuff, fun, fun fun!):

protected bool Compile(string assyFilename, List<string> sources, List<string> refs, bool generateExecutable = false)

{

bool ok = false;

CSharpCodeProvider provider = new CSharpCodeProvider();

CompilerParameters parameters = new CompilerParameters();

parameters.IncludeDebugInformation = true;

parameters.GenerateInMemory = false;

parameters.GenerateExecutable = generateExecutable;

parameters.ReferencedAssemblies.Add("System.dll");

parameters.ReferencedAssemblies.Add("System.Data.dll");

parameters.ReferencedAssemblies.Add("System.Data.Linq.dll");

parameters.ReferencedAssemblies.Add("System.Core.dll");

parameters.ReferencedAssemblies.Add("System.Net.dll");

parameters.ReferencedAssemblies.Add("System.Net.Http.dll");

parameters.ReferencedAssemblies.Add("System.Xml.dll");

parameters.ReferencedAssemblies.Add("System.Xml.Linq.dll");

parameters.ReferencedAssemblies.Add("Clifton.Core.dll");

parameters.ReferencedAssemblies.AddRange(refs.ToArray());

parameters.OutputAssembly = assyFilename;

if (generateExecutable)

{

parameters.MainClass = "App.Program";

}

results = provider.CompileAssemblyFromFile(parameters, sources.ToArray());

ok = !results.Errors.HasErrors;

if (results.Errors.HasErrors)

{

StringBuilder sb = new StringBuilder();

foreach (CompilerError error in results.Errors)

{

try

{

sb.AppendLine(String.Format("Error ({0} - {1}): {2}",

tempToTextBoxMap[Path.GetFileNameWithoutExtension(error.FileName) + ".cs"],

error.Line,

error.ErrorText));

}

catch

{

sb.AppendLine(error.ErrorText);

}

}

MessageBox.Show(sb.ToString(), assyFilename, MessageBoxButtons.OK, MessageBoxIcon.Error);

}

return ok;

}

Had enough? No, of course not. Let's look at how the workflow code is generated!

The other core piece is this. Again ugly, again found in MenuController2.cs.

public string GetWorkflowCode(GraphicElement wf)

{

StringBuilder sb = new StringBuilder();

sb.AppendLine("namespace App");

sb.AppendLine("{");

sb.AppendLine("\tpublic partial class " + wf.Text);

sb.AppendLine("\t{");

sb.AppendLine("\t\tpublic static void Execute(" +

Clifton.Core.ExtensionMethods.ExtensionMethods.LeftOf(wf.Text, "Workflow") +

" packet)");

sb.AppendLine("\t\t{");

sb.AppendLine("\t\t\t" + wf.Text + " workflow = new " + wf.Text + "();");

GraphicElement el = FindStartOfWorkflow(wf);

while (el != null)

{

sb.AppendLine("\t\t\tworkflow." + el.Text + "(packet);");

el = NextElementInWorkflow(el);

}

sb.AppendLine("\t\t}");

sb.AppendLine("\t}");

sb.AppendLine("}");

return sb.ToString();

}

Gotta love the hardcoded namespace and case-sensitive "Workflow" name parsing.

We find the start of the workflow by identifying the shape that has only a connector's start point attached to it (something I quite glossed over in the ooh, lookatthat part earlier):

protected GraphicElement FindStartOfWorkflow(GraphicElement wf)

{

GraphicElement start = null;

foreach (GraphicElement srcEl in canvasController.Elements.

Where(srcEl => wf.DisplayRectangle.Contains(srcEl.DisplayRectangle)))

{

if (!srcEl.IsConnector && srcEl != wf)

{

if (srcEl.Connections.Count == 0)

{

start = srcEl;

break;

}

if (srcEl.Connections.Count == 1 && ((Connection)srcEl.Connections[0]).ToConnectionPoint.Type == FlowSharpLib.GripType.Start)

{

start = srcEl;

break;

}

}

}

return start;

}

And then next step in the workflow is identified by figuring out to what shape the connector's end point is attached. Now, honestly, I don't know know how robust this code is, and I seriously doubt it is very robust.

protected GraphicElement NextElementInWorkflow(GraphicElement el)

{

GraphicElement ret = null;

if (el.Connections.Count == 1)

{

if (((Connector)((Connection)el.Connections[0]).ToElement).EndConnectedShape != el)

{

ret = ((Connector)((Connection)el.Connections[0]).ToElement).EndConnectedShape;

}

}

else if (el.Connections.Count == 2)

{

if (((Connector)((Connection)el.Connections[0]).ToElement).StartConnectedShape == el)

{

ret = ((Connector)((Connection)el.Connections[0]).ToElement).EndConnectedShape;

}

else if (((Connector)((Connection)el.Connections[1]).ToElement).StartConnectedShape == el)

{

ret = ((Connector)((Connection)el.Connections[1]).ToElement).EndConnectedShape;

}

}

return ret;

}

OK, hopefully NOW you've had enough!

This is an example of hosting a semantic web server.

(larger image)

Try it with Article\st_text.fsd. Run the "app", then in the browser, give it something to output to the console window with, for example, the URL localhost:8001/ST_Text?text=Hello+World

This is a bit like pulling oneself up by the bootstraps, because, you see, what the above "app" is doing is using the module manager, service manager, semantic pub/sub, etc., to runtime load modules that register themselves as semantic subscribers, and the web server parses the route to instantiate the semantic type, which then is published, and the subscriber outputs the text to the console window. (It's just a demo of all the cool things that you can do!) As a proof of concept, this shows that FlowSharpCode could be used to implement itself and very well might be in the future.

As an exercise for the reader, there's a "speak receptor.fsd" component in Article folder. Create a semantic type (use ST_Text as a template) called ST_Speak, import the speak receptor component, add a route for "st_speak", and run the application with the URL localhost:8001/ST_Speak?text=Hello+World. You'll have to place the ST_Speak class and the speak receptor in the right assemblies (hint, ungroup the assemblies in order to place shapes so they are contained by the correct assembly shapes.)

Here's my short list:

- It is so ridiculously simple to create an assembly and reference it

- I'm having lots of fun simply copying a group of shapes (along with their code) onto another drawing

- I like the packet workflow approach -- it actually makes code really simple, modular, and thread safe. Method parameters and return values are fine, but packetized workflows make things really uniform and trivial to add or remove workflow steps. Probably not to everyone's liking though.

- It is actually quite fun to work this way. The Intellisense is a bit limited, but I find that I don't miss it. The IDE can stand for tons of improvement, but it's useable as is.

- I can just imagine the howls of protest if you were to try to introduce this approach in mainstream development houses (granted, with a more advanced version than this code.) And I get a sort of sadistic pleasure in imagining those howls.

- The idea of mixing code languages, platforms, back-end, front-end, etc., onto a single surface is quite fun. I had originally thought of doing a demo of a C# client making REST calls to a Django/Python back-end, and might do that at some point.

- Cleaning up the code

- Adding multiple document support

- Improving usability - one of my top items is collapsing a part of the diagram to an off-page reference, so these diagrams are manageable.

Play!

Play with the examples, try a few simple things yourself. Just remember the hard-coded constraints the code imposes on you, like the namespace, the Program class name, etc. There's some quirks with FlowSharp that I discovered that I'll be addressing, but mostly I'm interested in what you think of this crazy approach, what you'd like to see, and whether you think this concept is worth pursuing further (I do, so I suppose it doesn't matter what you think, mwahaha!) And use the GitHub Issues for any feedback if possible, otherwise post your feedback here in the comments section and I'll do my best to add it to the project's Issues.