Introduction

A software-based Finite State Machines (FSM) is an implementation method used to decompose a design into states and events. Simple embedded devices with no operating system employ single threading such that the state machines run on a single “thread”. More complex systems use multithreading to divvy up the processing.

Many FSM implementations exist including one I wrote about here on Code Project entitled “State Machine Design in C++”. The article covers how to create C++ state machines using the StateMachine base class. What is missing, however, is how to integrate multiple state machines into the context of a multithreaded environment.

“Asynchronous Multicast Delegates in C++” is another article I wrote on Code Project. This design provides a C++ delegate library that is capable of synchronous and asynchronous invocations on any callable function.

This article combines the two previously described techniques, state machines and asynchronous multicast delegates, into a single project. In the previous articles, it may not be readily apparent using simple examples how multiple state machines coordinate activities and dispatch events to each other. The goal for the article is to provide a complete working project with threads, timers, events, and state machines all working together. To illustrate the concept, the example project implements a state-based self-test engine utilizing asynchronous communication between threads.

I won’t be re-explaining the StateMachine and Delegate<> implementations as the prior articles do that already. The primary focus is on how to combine the state machine and delegates into a single framework.

This article is similar in concept to my article “C++ State Machine with Threads”. That article utilized AsyncCallback<> for the inter-thread messaging whereas this article utilizes Delegate<>. AsyncCallback<> is a simple, compact implementation with limited callback function types and signatures. The advantage of AsyncCallback<> is that the implementation is more compact and simple at the expense of only being able to target free or static functions with a single function argument. The Delegate<> implementation illustrated here allows asynchronous callbacks on any function type, including member functions, with any function signature thus simplifying integration with StateMachine.

CMake is used to create the build files. CMake is free and open-source software. Windows, Linux and other toolchains are supported. See the CMakeLists.txt file for more information.

See GitHub for latest source code:

Related GitHub repositories:

Asynchronous Delegate Callbacks

If you’re not familiar with a delegate, the concept is quite simple. A delegate can be thought of as a super function pointer. In C++, there's no pointer type capable of pointing to all the possible function variations: instance member, virtual, const, static, and free (global). A function pointer can’t point to instance member functions, and pointers to member functions have all sorts of limitations. However, delegate classes can, in a type-safe way, point to any function provided the function signature matches. In short, a delegate points to any function with a matching signature to support anonymous function invocation.

Asynchronous delegates take the concept a bit further and permit anonymous invocation of any function on a client specified thread of control. The function and all arguments are safely called from a destination thread simplifying inter-thread communication and eliminating cross-threading errors.

The Delegate<> framework is used throughout to provide asynchronous callbacks making an effective publisher and subscriber mechanism. A publisher exposes a delegate container interface and one or more subscribers add delegate instances to the container to receive anonymous callbacks.

The first place it's used is within the SelfTest class where the SelfTest::CompletedCallback delegate container allows subscribers to add delegates. Whenever a self-test completes a SelfTest::CompletedCallback callback is invoked notifying registered clients. SelfTestEngine registers with both CentrifugeTest and PressureTest to get asynchronously informed when the test is complete.

The second location is the user interface registers with SelfTestEngine::StatusCallback. This allows a client, running on another thread, to register and receive status callbacks during execution. MulticastDelegateSafe1<> allows the client to specify the exact callback thread making it easy to avoid cross-threading errors.

The final location is within the Timer class, which fires periodic callbacks on a registered callback function. A generic, low-speed timer capable of calling a function on the client-specified thread is quite useful for event driven state machines where you might want to poll for some condition to occur. In this case, the Timer class is used to inject poll events into the state machine instances.

Self-Test Subsystem

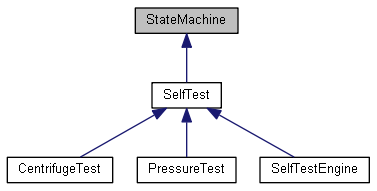

Self-tests execute a series of tests on hardware and mechanical systems to ensure correct operation. In this example, there are four state machine classes implementing our self-test subsystem as shown in the inheritance diagram below:

Figure 1: Self-Test Subsystem Inheritance Diagram

SelfTestEngine

SelfTestEngine is thread-safe and the main point of contact for client’s utilizing the self-test subsystem. CentrifugeTest and PressureTest are members of SelfTestEngine. SelfTestEngine is responsible for sequencing the individual self-tests in the correct order as shown in the state diagram below.

Figure 2: SelfTestEngine State Machine

The Start event initiates the self-test engine. SelfTestEngine::Start() is an asynchronous function that reinvokes the Start() function if the caller is not on the correct execution thread. Perform a simple check whether the caller is executing on the desired thread of control. If not, a temporary asynchronous delegate is created on the stack and then invoked. The delegate and all the caller’s original function arguments are duplicated on the heap and the function is reinvoked on m_thread. This is an elegant way to create asynchronous APIs with the absolute minimum of effort. Since Start() is asynchronous, it is thread-safe to be called by any client running on any thread.

void SelfTestEngine::Start(const StartData* data)

{

if (m_thread.GetThreadId() != WorkerThread::GetCurrentThreadId())

{

Delegate1<const StartData*>& delegate =

MakeDelegate(this, &SelfTestEngine::Start, &m_thread);

delegate(data);

return;

}

BEGIN_TRANSITION_MAP TRANSITION_MAP_ENTRY (ST_START_CENTRIFUGE_TEST) TRANSITION_MAP_ENTRY (CANNOT_HAPPEN) TRANSITION_MAP_ENTRY (CANNOT_HAPPEN) TRANSITION_MAP_ENTRY (EVENT_IGNORED) TRANSITION_MAP_ENTRY (EVENT_IGNORED) END_TRANSITION_MAP(data)

}

When each self-test completes, the Complete event fires causing the next self-test to start. After all of the tests are done, the state machine transitions to Completed and back to Idle. If the Cancel event is generated at any time during execution, a transition to the Failed state occurs.

The SelfTest base class provides three states common to all SelfTest-derived state machines: Idle, Completed, and Failed. SelfTestEngine then adds two more states: StartCentrifugeTest and StartPressureTest.

SelfTestEngine has one public event function, Start(), that starts the self-tests. SelfTestEngine::StatusCallback is an asynchronous callback allowing clients to register for status updates during testing. A WorkerThread instance is also contained within the class. All self-test state machine execution occurs on this thread.

class SelfTestEngine : public SelfTest

{

public:

static MulticastDelegateSafe1<const SelfTestStatus&> StatusCallback;

static SelfTestEngine& GetInstance();

void Start(const StartData* data);

WorkerThread& GetThread() { return m_thread; }

static void InvokeStatusCallback(std::string msg);

private:

SelfTestEngine();

void Complete();

CentrifugeTest m_centrifugeTest;

PressureTest m_pressureTest;

WorkerThread m_thread;

StartData m_startData;

enum States

{

ST_START_CENTRIFUGE_TEST = SelfTest::ST_MAX_STATES,

ST_START_PRESSURE_TEST,

ST_MAX_STATES

};

STATE_DECLARE(SelfTestEngine, StartCentrifugeTest, StartData)

STATE_DECLARE(SelfTestEngine, StartPressureTest, NoEventData)

BEGIN_STATE_MAP

STATE_MAP_ENTRY(&Idle)

STATE_MAP_ENTRY(&Completed)

STATE_MAP_ENTRY(&Failed)

STATE_MAP_ENTRY(&StartCentrifugeTest)

STATE_MAP_ENTRY(&StartPressureTest)

END_STATE_MAP

};

As mentioned previously, the SelfTestEngine registers for asynchronous callbacks from each sub self-tests (i.e., CentrifugeTest and PressureTest) as shown below. When a sub self-test state machine completes, the SelfTestEngine::Complete() function is called. When a sub self-test state machine fails, the SelfTestEngine::Cancel() function is called.

SelfTestEngine::SelfTestEngine() :

SelfTest(ST_MAX_STATES),

m_thread("SelfTestEngine")

{

m_centrifugeTest.CompletedCallback +=

MakeDelegate(this, &SelfTestEngine::Complete, &m_thread);

m_centrifugeTest.FailedCallback +=

MakeDelegate<SelfTest>(this, &SelfTest::Cancel, &m_thread);

m_pressureTest.CompletedCallback +=

MakeDelegate(this, &SelfTestEngine::Complete, &m_thread);

m_pressureTest.FailedCallback +=

MakeDelegate<SelfTest>(this, &SelfTest::Cancel, &m_thread);

}

The SelfTest base class generates the CompletedCallback and FailedCallback within the Completed and Failed states respectively as seen below:

STATE_DEFINE(SelfTest, Completed, NoEventData)

{

SelfTestEngine::InvokeStatusCallback("SelfTest::ST_Completed");

if (CompletedCallback)

CompletedCallback();

InternalEvent(ST_IDLE);

}

STATE_DEFINE(SelfTest, Failed, NoEventData)

{

SelfTestEngine::InvokeStatusCallback("SelfTest::ST_Failed");

if (FailedCallback)

FailedCallback();

InternalEvent(ST_IDLE);

}

One might ask why the state machines use asynchronous delegate callbacks. If the state machines are on the same thread, why not use a normal, synchronous callback instead? The problem to prevent is a callback into a currently executing state machine, that is, the call stack wrapping back around into the same class instance. For example, the following call sequence should be prevented: SelfTestEngine calls CentrifugeTest calls back SelfTestEngine. An asynchronous callback allows the stack to unwind and prevents this unwanted behavior.

CentrifugeTest

The CentrifugeTest state machine diagram shown below implements the centrifuge self-test described in "State Machine Design in C++". CentrifugeTest uses state machine inheritance by inheriting the Idle, Completed and Failed states from the SelfTest class. The difference here is that the Timer class is used to provide Poll events via asynchronous delegate callbacks.

Figure 3: CentrifugeTest State Machine

Timer

The Timer class provides a common mechanism to receive function callbacks by registering with Expired. Start() starts the callbacks at a particular interval. Stop() stops the callbacks.

class Timer

{

public:

static const DWORD MS_PER_TICK;

SinglecastDelegate0<> Expired;

Timer(void);

~Timer(void);

void Start(DWORD timeout);

void Stop();

...

All Timer instances are stored in a private static list. The WorkerThread::Process() loop periodically services all the timers within the list by calling Timer::ProcessTimers(). Clients registered with Expired are invoked whenever the timer expires.

case WM_USER_TIMER:

Timer::ProcessTimers();

break;

Win32 and std::thread Worker Threads

The source code provides two alternative WorkerThread implementations. The Win32 version is contained within WorkerThreadWin.cpp/h and relies upon the Windows API. The std::thread version is located at WorkerThreadStd.cpp/h and uses the C++11 threading features. One of the two implementations is selected by defining either USE_WIN32_THREADS or USE_STD_THREADS located within DelegateOpt.h.

See Win32 Thread Wrapper with Synchronized Start and C++ std::thread Event Loop with Message Queue and Timer for more information about the underlying thread class implementations.

Heap vs. Pool

On some projects, it is not desirable to utilize the heap to retrieve dynamic storage. Maybe the project is mission critical and the risk of a memory fault due to a fragmented heap in unacceptable. Or maybe heap overhead and nondeterministic execution is considered too great. Either way, the project includes a fixed block memory allocator to divert all memory allocations to a fixed block allocator. Enable the fixed block allocator on the delegate library by defining USE_XALLOCATOR in DelegateOpt.h. To enable the allocator on state machines, uncomment XALLOCATOR in StateMachine.h.

See Replace malloc/free with a Fast Fixed Block Memory Allocator for more information on xallocator.

Poll Events

CentrifugeTest has a Timer instance and registers for callbacks. The callback function, a thread instance and a this pointer is provided to Register() facilitating the asynchronous callback mechanism.

m_pollTimer.Expired = MakeDelegate(this, &CentrifugeTest::Poll,

&SelfTestEngine::GetInstance().GetThread());

When the timer is started using Start(), the Poll() event function is periodically called at the interval specified. Notice that when the Poll() external event function is called, a transition to either WaitForAcceleration or WaitForDeceleration is performed based on the current state of the state machine. If Poll() is called at the wrong time, the event is silently ignored.

void CentrifugeTest::Poll()

{

BEGIN_TRANSITION_MAP TRANSITION_MAP_ENTRY (EVENT_IGNORED) TRANSITION_MAP_ENTRY (EVENT_IGNORED) TRANSITION_MAP_ENTRY (EVENT_IGNORED) TRANSITION_MAP_ENTRY (EVENT_IGNORED) TRANSITION_MAP_ENTRY (ST_WAIT_FOR_ACCELERATION) TRANSITION_MAP_ENTRY (ST_WAIT_FOR_ACCELERATION) TRANSITION_MAP_ENTRY (ST_WAIT_FOR_DECELERATION) TRANSITION_MAP_ENTRY (ST_WAIT_FOR_DECELERATION) END_TRANSITION_MAP(NULL)

}

STATE_DEFINE(CentrifugeTest, Acceleration, NoEventData)

{

SelfTestEngine::InvokeStatusCallback("CentrifugeTest::ST_Acceleration");

m_pollTimer.Start(10);

}

User Interface

The project doesn’t have a user interface except the text console output. For this example, the “user interface” just outputs self-test status messages on the user interface thread via the SelfTestEngineStatusCallback() function:

WorkerThread userInterfaceThread("UserInterface");

void SelfTestEngineStatusCallback(const SelfTestStatus& status)

{

cout << status.message.c_str() << endl;

}

Before the self-test starts, the user interface registers with the SelfTestEngine::StatusCallback callback.

SelfTestEngine::StatusCallback +=

MakeDelegate(&SelfTestEngineStatusCallback, &userInterfaceThread);

The user interface thread here is just used to simulate callbacks to a GUI library normally running in a separate thread of control.

Run-Time

The program’s main() function is shown below. It creates the two threads, registers for callbacks from SelfTestEngine, then calls Start() to start the self-tests.

int main(void)

{

userInterfaceThread.CreateThread();

SelfTestEngine::GetInstance().GetThread().CreateThread();

SelfTestEngine::StatusCallback +=

MakeDelegate(&SelfTestEngineStatusCallback, &userInterfaceThread);

SelfTestEngine::GetInstance().CompletedCallback +=

MakeDelegate(&SelfTestEngineCompleteCallback, &userInterfaceThread);

ThreadWin::StartAllThreads();

StartData startData;

startData.shortSelfTest = TRUE;

SelfTestEngine::GetInstance().Start(&startData);

while (!selfTestEngineCompleted)

Sleep(10);

SelfTestEngine::StatusCallback -=

MakeDelegate(&SelfTestEngineStatusCallback, &userInterfaceThread);

SelfTestEngine::GetInstance().CompletedCallback -=

MakeDelegate(&SelfTestEngineCompleteCallback, &userInterfaceThread);

userInterfaceThread.ExitThread();

SelfTestEngine::GetInstance().GetThread().ExitThread();

return 0;

}

SelfTestEngine generates asynchronous callbacks on the UserInteface thread. The SelfTestEngineStatusCallback() callback outputs the message to the console.

void SelfTestEngineStatusCallback(const SelfTestStatus& status)

{

cout << status.message.c_str() << endl;

}

The SelfTestEngineCompleteCallback() callback sets a flag to let the main() loop exit.

void SelfTestEngineCompleteCallback()

{

selfTestEngineCompleted = TRUE;

}

Running the project outputs the following console messages:

Figure 4: Console Output

Conclusion

The StateMachine and Delegate<> implementations can be used separately. Each is useful unto itself. However, combining the two offers a novel framework for multithreaded state-driven application development. The article has shown how to coordinate the behavior of state machines when multiple threads are used, which may not be entirely obvious when looking at simplistic, single threaded examples.

I’ve successfully used ideas similar to this on many different PC and embedded projects. The code is portable to any platform with a small amount of effort. I particularly like the idea of asynchronous delegate callbacks because it effectively hides inter-thread communication and the organization of the state machines makes creating and maintaining self-tests easy.

References

History

- 11th January, 2017

- 19th January, 2017

- Minor updates to article

- Updated attached source with updated

StateMachine implementation

- 5th February, 2017

- Updated references to supporting articles