After learning a bit about React and getting into Redux, it’s really confusing how it all works.

Actions, reducers, action creators, middleware, pure functions, immutability…

Most of these terms seem totally foreign.

So in this post, we’re going to demystify how Redux works with some visuals and some examples. As in the last post, I’ll try to explain Redux in simple terms before tackling the terminology.

If you’re not yet sure what Redux is for or why you should use it, read this post first and then come back here.

First: Plain React State

We’ll start with an example of plain old React state, and then add Redux piece-by-piece.

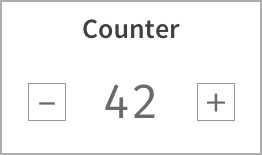

Here is a counter:

And here’s the code (I left out the CSS to keep this simple, so it won’t be as pretty as the image):

import React from 'react';

class Counter extends React.Component {

state = { count: 0 }

increment = () => {

this.setState({

count: this.state.count + 1

});

}

decrement = () => {

this.setState({

count: this.state.count - 1

});

}

render() {

return (

<div>

<h2>Counter</h2>

<div>

<button onClick={this.decrement}>-</button>

<span>{this.state.count}</span>

<button onClick={this.increment}>+</button>

</div>

</div>

)

}

}

export default Counter;

As a quick review, here’s how this works:

- The

count state is stored in the top level Counter component - When the user clicks “

+”, the button’s onClick handler is called, which is bound to the increment function in the Counter component. - The

increment function updates the state with the new count. - Because state was changed, React re-renders the

Counter component (and its children), and the new counter value is displayed.

If you need more detail about how state changes work, go read A Visual Guide to State in React and then come back here. Seriously: if the above was not review for you, you need to learn how React state works before you learn Redux.

Quick Setup

If you’d like to follow along with the code, create a project now:

- Install

create-react-app if you don’t have it (npm install -g create-react-app) - Create a project:

create-react-app redux-intro - Open src/index.js and replace it with this:

import React from 'react';

import { render } from 'react-dom';

import Counter from './Counter';

const App = () => (

<div>

<Counter />

</div>

);

render(<App />, document.getElementById('root'));

- Create a src/Counter.js with the code from the

Counter example above.

Now: Add Redux

As discussed in Part 1, Redux keeps the state of your app in a single store. Then, you can extract parts of that state and plug it into your components as props. This lets you keep data in one global place (the store) and feed it directly to any component in the app, without the gymnastics of passing props down multiple levels.

Side note: You’ll often see the words “state” and “store” used interchangably. Technically, the state is the data, and the store is where it’s kept.

As we go through the steps below, follow along in your editor! It will help you understand how this works (and we’ll get to work through some errors together).

Add Redux to the project:

$ yarn add redux react-redux

redux vs react-redux

Wait – 2 libraries? “What’s react-redux,” you say? Well, I’ve kinda been lying to you (sorry).

See, redux gives you a store, and lets you keep state in it, and get state out, and respond when the state changes. But that’s all it does. It’s actually react-redux that lets you connect pieces of the state to React components. That’s right: redux knows nothing about React at all.

These libraries are like two peas in a pod. 99.999% of the time, when anyone mentions “Redux” in the context of React, they are referring to both of these libraries in tandem. So keep that in mind when you see Redux mentioned on StackOverflow, or Reddit, or elsewhere.

Last Things First

Most tutorials start by creating a store, setting up Redux, writing a reducer, and so on. Lots must happen before anything appears on screen.

I’m going to take a backwards approach, and it will take just as much code to make things appear on screen, but hopefully the motivation behind each step will be clearer.

Back to the Counter app, let’s just imagine for a second that we moved the component’s state into Redux.

We’ll remove the state from the component, since we’ll be getting that from Redux soon:

import React from 'react';

class Counter extends React.Component {

increment = () => {

}

decrement = () => {

}

render() {

return (

<div>

<h2>Counter</h2>

<div>

<button onClick={this.decrement}>-</button>

<span>{this.props.count}</span>

<button onClick={this.increment}>+</button>

</div>

</div>

)

}

}

export default Counter;

Wiring Up The Counter

Notice that {this.state.count} changed to {this.props.count}. This won’t work yet, of course, because the Counter is not receiving a count prop. We’re going to use Redux to inject that.

To get the count out of Redux, we first need to import the connect function at the top:

import { connect } from 'react-redux';

Then we need to “connect” the Counter component to Redux at the bottom:

function mapStateToProps(state) {

return {

count: state.count

};

}

export default connect(mapStateToProps)(Counter);

This will fail with an error (more on that in a second).

Where previously we were exporting the component itself, now we’re wrapping it with this connect function call.

What’s connect?

You might notice the call looks little… weird. Why connect(mapStateToProps)(Counter) and not connect(mapStateToProps, Counter) or connect(Counter, mapStateToProps)? What’s that doing?

It’s written this way because connect is a higher-order function, which is a fancy way of saying it returns a function when you call it. And then calling that function with a component returns a new (wrapped) component.

Another name for this is a higher-order component (aka “HOC”). HOCs have gotten some bad press lately, but they’re still quite useful, and connect is a good example of a useful one.

What connect does is hook into Redux, pull out the entire state, and pass it through the mapStateToProps function that you provide. This needs to be a custom function because only you will know the “shape” of the state in Redux.

connect passes the entire state as if to say, “Hey, tell me what you need out of this jumbled mess.”

The object you return from mapStateToProps gets fed into your component as props. The example above will pass state.count as the value of the count prop: the keys in the object become prop names, and their corresponding values become the props’ values. So you see, this function literally defines a mapping from state into props.

Errors Mean Progress!

If you’re following along, you will see an error like this in the console:

Could not find “store” in either the context or props of “Connect(Counter)”. Either wrap the root component in a <provider>, or explicitly pass "store" as a prop to "Connect(Counter)".

Since connect pulls data from the Redux store, and we haven’t set up a store or told the app how to find it, this error is pretty logical. Redux has no dang idea what’s going on right now.

Provide a Store

Redux holds the global state for the entire app, and by wrapping the entire app with the Provider component from react-redux, every component in the app tree will be able to use connect to access the Redux store if it wants to.

This means App, and children of App (like Counter), and children of their children, and so on – all of them can now access the Redux store, but only if they are explicitly wrapped by a call to connect.

I’m not saying to actually do that – connecting every single component would be a bad idea (messy design, and slow too).

This Provider thing might seem like total magic right now. It is a little bit; it actually uses React’s “context” feature under the hood.

It’s like a secret passageway connected to every component, and using connect opens the door to the passageway.

Imagine pouring syrup on a pile of pancakes, and how it manages to make its way into ALL the pancakes even though you just poured it on the top one. Provider does that for Redux.

In src/index.js, import the Provider and wrap the:

import { Provider } from 'react-redux';

...

const App = () => (

<Provider>

<Counter/>

</Provider>

);

We’re still getting that error though – that’s because Provider needs a store to work with. It’ll take the store as a prop, but we need to create one first.

Create the Store

Redux comes with a handy function that creates stores, and it’s called createStore. Yep. Let’s make a store and pass it to Provider:

import { createStore } from 'redux';

const store = createStore();

const App = () => (

<Provider store={store}>

<Counter/>

</Provider>

);

Another error, but different this time:

Expected the reducer to be a function.

So, here’s the thing about Redux: it’s not very smart. You might expect that by creating a store, it would give you a nice default value for the state inside that store. Maybe an empty object?

But no: Redux makes zero assumptions about the shape of your state. It’s up to you! It could be an object, or a number, or a string, or whatever you need. So we have to provide a function that will return the state. That function is called a reducer (we’ll see why in a minute). So let’s make the simplest one possible, pass it into createStore, and see what happens:

function reducer() {

}

const store = createStore(reducer);

The Reducer Should Always Return Something

The error is different now:

Cannot read property ‘count’ of undefined

It’s breaking because we’re trying to access state.count, but state is undefined. Redux expected our reducer function to return a value for state, except that it (implicitly) returned undefined. Things are rightfully broken.

The reducer is expected to return the state. It’s actually supposed to take the current state and return the new state, but nevermind; we’ll come back to that.

Let’s make the reducer return something that matches the shape we need: an object with a count property.

function reducer() {

return {

count: 42

};

}

Hey! It works! The count now appears as “42”. Awesome.

Just one thing though: the count is forever stuck at 42.

The Story So Far

Before we get into how to actually update the counter, let’s look at what we’ve done uptil now:

- We wrote a

mapStateToProps function that does what the name says: transforms the Redux state into an object containing props. - We connected the Redux store to our

Counter component with the connect function from react-redux, using the mapStateToProps function to configure how the connection works. - We created a

reducer function to tell Redux what our state should look like. - We used the ingeniously-named

createStore function to create a store, and passed it the reducer. - We wrapped our whole app in the

Provider component that comes with react-redux, and passed it our store as a prop. - The app works flawlessly, except the fact that the

counter is stuck at 42.

With me so far?

Interactivity (Making It Work)

So far this is pretty lame, I know. You could’ve written a static HTML page with the number “42” and 2 broken buttons in 60 seconds flat, yet here you are, reading how to overcomplicate that very same thing with React and Redux and who knows what else.

I promise this next section will make it all worthwhile.

Actually, no. I take that back. A simple Counter app is a great teaching tool, but Redux is absolutely overkill for something like this. React state is perfectly fine for something so simple. Heck, even plain JS would work great. Pick the right tool for the job. Redux is not always that tool. But I digress.

Initial State

So we need a way to tell Redux to change the counter.

Remember the reducer function we wrote? (of course you do, it was 2 minutes ago)

Remember how I mentioned it takes the current state and returns the new state? Well, I lied again. It actually takes the current state and an action, and then it returns the new state. We should have written it like this:

function reducer(state, action) {

return {

count: 42

};

}

The very first time Redux calls this function, it will pass undefined as the state. That is your cue to return the initial state. For us, that’s probably an object with a count of 0.

It’s common to write the initial state above the reducer, and use ES6’s default argument feature to provide a value for the state argument when it’s undefined.

const initialState = {

count: 0

};

function reducer(state = initialState, action) {

return state;

}

Try this out. It should still work, except now the counter is stuck at 0 instead of 42. Awesome.

Action

We’re finally ready to talk about the action parameter. What is it? Where does it come from? How can we use it to change the damn counter?

An “action” is a JS object that describes a change that we want to make. The only requirement is that the object needs to have a type property, and its value should be a string. Here’s an example of an action:

{

type: "INCREMENT"

}

Here’s another one:

{

type: "DECREMENT"

}

Are the gears turning in your head? Do you know what we’re going to do next?

Respond to Actions

Remember the reducer’s job is to take the current state and an action and figure out the new state. So if the reducer received an action like { type: "INCREMENT" }, what might you want to return as the new state?

If you answered something like this, you’re on the right track:

function reducer(state = initialState, action) {

if(action.type === "INCREMENT") {

return {

count: state.count + 1

};

}

return state;

}

It’s common to use a switch statement with cases for each action you want to handle. Change your reducer to look like this:

function reducer(state = initialState, action) {

switch(action.type) {

case 'INCREMENT':

return {

count: state.count + 1

};

case 'DECREMENT':

return {

count: state.count - 1

};

default:

return state;

}

}

Always Return a State

You’ll notice that there’s always the fallback case where all it does is return state. This is important, because Redux can (will) call your reducer with actions that it doesn’t know what to do with. In fact, the very first action you’ll receive is { type: "@@redux/INIT" }. Try putting a console.log(action) above the switch and see.

Remember that the reducer’s job is to return a new state, even if that state is unchanged from the current one. You never want to go from “having a state” to “state = undefined”, right? That’s what would happen if you left off the default case. Don’t do that.

Never Change State

One more thing to never do: do not mutate the state. State is immutable. You must never change it. That means you can’t do this:

function brokenReducer(state = initialState, action) {

switch(action.type) {

case 'INCREMENT':

state.count++;

return state;

case 'DECREMENT':

state.count--;

return state;

default:

return state;

}

}

You also can’t do things like state.foo = 7, or state.items.push(newItem), or delete state.something.

Think of it like a game where the only thing you can do is return { ... }. It’s a fun game. Maddening at first. But you’ll get better at it with practice.

All These Rules…

Always return a state, never change state, don’t connect every component, eat your broccoli, don’t stay out past 11… it’s exhausting. It’s like a rules factory, and I don’t even know what that is.

Yeah, Redux can be like an overbearing parent. But it comes from a place of love. Functional programming love.

Redux is built on the idea of immutability, because mutating global state is the road to ruin.

Have you ever kept a global object and used it to pass state around an app? It works great at first. Nice and easy. And then the state starts changing in unpredictable ways and it becomes impossible to find the code that’s changing it.

Redux avoids these problems with some simple rules. State is read-only, and actions are the only way to modify it. Changes happen one way, and one way only: action -> reducer -> new state. The reducer function must be “pure” – it cannot modify its arguments.

There are even addon packages that let you log every action that comes through, rewind and replay them, and anything else you could imagine. Time-travel debugging was one of the original motivations for creating Redux.

Where Do Actions Come From?

One piece of this puzzle remains: we need a way to feed an action into our reducer function so that we can increment and decrement the counter.

Actions are not born, but they are dispatched, with a handy function called dispatch.

The dispatch function is provided by the instance of the Redux store. That is to say, you can’t just import { dispatch } and be on your way. You can call store.dispatch(someAction), but that’s not very convenient since the store instance is only available in one file.

As luck would have it, the connect function has our back. In addition to injecting the result of mapStateToProps as props, connect also injects the dispatch function as a prop. And with that bit of knowledge, we can finally get the counter working again.

Here is the final component in all its glory. If you’ve been following along, the only things that changed are the implementations of increment and decrement: they now call the dispatch prop, passing it an action.

import React from 'react';

import { connect } from 'react-redux';

class Counter extends React.Component {

increment = () => {

this.props.dispatch({ type: 'INCREMENT' });

}

decrement = () => {

this.props.dispatch({ type: 'DECREMENT' });

}

render() {

return (

<div>

<h2>Counter</h2>

<div>

<button onClick={this.decrement}>-</button>

<span>{this.props.count}</span>

<button onClick={this.increment}>+</button>

</div>

</div>

)

}

}

function mapStateToProps(state) {

return {

count: state.count

};

}

export default connect(mapStateToProps)(Counter);

The code for the entire project (all two files of it) can be found on Github.

What Now?

With the Counter app under your belt, you are well-equipped to learn more about Redux.

“What?! There’s more?!”

There is much I haven’t covered here, in the hopes of making this guide easily digestible – action constants, action creators, middleware, thunks and asynchronous calls, selectors, and on and on. There’s a lot. The Redux docs are well-written and cover all that and more.

But you’ve got the basic idea now. Hopefully you understand how data flows in Redux (dispatch(action) -> reducer -> new state -> re-render), and what a reducer does, and what an action is, and how that all fits together.

I’m putting together a new course that will cover all of this and more. If you want to know when that’s available, drop your email in the box below and I’ll give you a shout.

How Does Redux Work? was originally published by Dave Ceddia at Dave Ceddia on October 29, 2017.

CodeProject