Introduction

String comparisons must be one of the most common things we do in C#; and string comparisons can be really expensive! So it's worthwhile knowing the what, when and why to improving string comparison performance.

In this article, I will explore one way – string interning.

What is String Interning?

String interning refers to having a single copy of each unique string in an string intern pool, which is via a hash table in the.NET common language runtime (CLR). Where the key is a hash of the string and the value is a reference to the actual String object.

So if I have the same string occurring 100 times, interning will ensure only one occurrence of that string is actually allocated any memory. Also, when I wish to compare strings, if they are interned, then I just need to do a reference comparison.

String Interning Mechanics

In this example, I explicitly intern string literals just for demonstration purposes.

var s1 = string.Intern("stringy");

var s2 = string.Intern("stringy");

var s3 = string.Intern("stringy");

Line 1

- This new “

stringy” is hashed and the hash is looked up in our pool (of course it's not there yet) - A copy of the “

stringy” object would be made - A new entry would be made to the interning hash table, with the key being the hash of “

stringy” and the value being a reference to the copy of “stringy” - Assuming application no longer references original “

stringy”, the GC can reclaim that memory

Line 2

- This new “

stringy” is hashed and the hash is looked up in our pool (which we just put there). The reference to the “stringy” copy is returned.

Line 3

Interning Depends on String Immutability

Take a classic example of string immutability:

var s1 = "stringy";

s1 += " new string";

We know that when line 2 is executed, the “stringy” object is de-referenced and left for garbage collection; and s1 then points to the new String object “stringy new string”.

String interning works because the CLR knows, categorically, that the String object referenced cannot change. Here, I’ve added a fourth line to the earlier example:

var s1 = string.Intern("stringy");

var s2 = string.Intern("stringy");

var s3 = string.Intern("stringy");

s1 += " new string";

Line 4

s1 doesn’t change because it is immutable; it now points to a new String object “stringy new string”.

s2 and s3 will still safely reference the copy that was made at line 1.

Using Interning in the .NET CLR

You’ve already seen a bit in the examples above. .NET offers two static string methods:

Intern(String str)

It hashes string str and checks the intern pool hash table and either:

- returns a reference to the (already) interned

string, if interned; or - a references to

str is added to the intern pool and this reference is returned

IsInterned(String str)

It hashes string str and checks the intern pool hash table. Rather than a standard bool, it returns either:

null, if not interned- a reference to the (already) interned

string, if interned

String literals (not generated in code) are automatically interned although CLR versions have varied in this behaviour, so if you expect strings interned, it is best to always do it explicitly in your code.

My Simple Test: Setup

I’ve run some timed tests on my aging i5 Windows 10 PC at home to provide some numbers to help explore the potential gains from string interning. I used the following test setup:

- Strings randomly generated

- All string comparisons are ordinal

- Strings are all the same length of 512 characters as I want the CLR to compare every character to force the worst-case (the CLR checks string length first for ordinal comparisons)

- The string added last (so to the end of the

List<T>) is also stored as a ‘known’ search term. This is because I am only exploring the worst-case approach - For the

List<T> interned, every string added to the list, and also the search term, were wrapped in the string.Intern(String str) method

I timed how long populating each collection took and then how long searching for the known search term took also, to the nearest millisecond.

The collections/approaches used for my tests:

List<T> with no interning used, searched via a foreach loop and string.Equals on each elementList<T> with no interning used, searched via the Contains methodList<T> with interning used, searched via a foreach loop and object.ReferenceEqualsHashSet<T>, searched via the Contains method

The main objective is to observe string search performance gains from using string interning with List<T> HashSet is just included as a baseline for known fast searches.

My Simple Test: Results

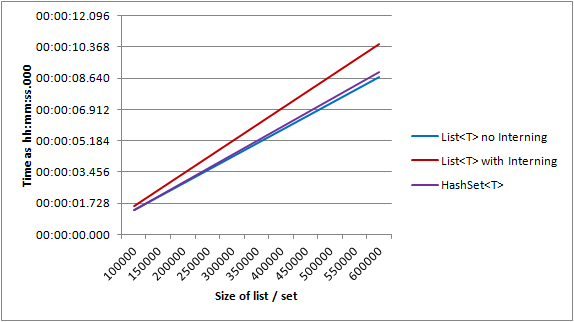

In Figure 1 below, I have plotted the size of collections in number of strings added, against the time taken to add that number of randomly generated strings. Clearly there is no significant difference in this operation, when using a HashSet<t> compared to a List<T> without interning. Perhaps if it had run to larger sets, the gap would widen further based on trend?

There is slightly more overhead when populating the List<T> with string interning, which is initially of no consequence but is growing faster than the other options.

Figure 1: Populating List<T> and HashSet<T> collections with random strings

Figure 2 shows the times for searching for the known string. All the times are pretty small for these collection sizes, but the growths are clear.

Figure 2: Times taken searching for a string known, which was added last

As expected, HashSet is O(1) and the others are O(N). The searches not utilising interning are clearly growing in time taken at a greater rate.

Conclusion

HashSet<T> is present in this article only as a baseline for fast searching and should obviously be your choice for speed where there are no constraints requiring a List<T>.

In scenarios where you must use a List<T> such as where you still wish to enumerate quickly through a collection, there are some performance gains to be had from using string interning, with benefits increasing as the size of the collection grows. The drawback is the slightly increased populating overhead (although I think it is fair to suggest that most real-world use cases would not involve populating the entire collection in one go).

The utility and behaviour of string interning, reminds me of database indexes – it takes a bit longer to add a new item but that item will be faster to find. So perhaps the same considerations for database indexes are true for string interning?

There is also the added bonus that string interning will prevent any duplicate strings being stored, which in some scenarios could mean substantial memory savings.

Potential Benefits

- Faster searching via object references

- Reduced memory usage because duplicate interned strings will only be stored once

Potential Performance Hit

- Memory referenced by the intern hash table is unlikely to be released until the CLR terminates

- You still need to create the string to be interned, which will be allocated memory (granted, this will then be garbage collected)

Sources

CodeProject