Introduction

In this article, I suppose that you have a good understanding of SQL already. I will introduce some concepts very briefly before moving on to Common Table Expressions.

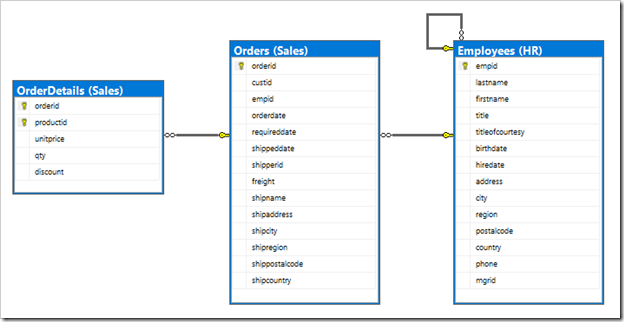

Below, you can find the relevant database diagram of the database that I will use in this article:

How is SQL Processed by SQL Server?

When we look at a basic SQL statement; the general structure looks like:

SELECT <field list>

FROM <table list>

WHERE <row predicates>

GROUP BY <group by list>

HAVING <aggregate predicates>

ORDER BY <field list>

As a mental picture, we see the order of execution as:

First, determine where the data will come from. This is indicated in the <table list>. This list can contain zero or more tables. When there are many tables, they can be joined using inner or outer join operators, and possibly also cross join operators. At this stage, we consider the Cartesian product of all the rows in all the tables.

select count(*) from [HR].[Employees]

select count(*) from [Sales].[Orders]

select count(*) from [HR].[Employees], [Sales].[Orders]

select 9 * 831

In the third query, we combine the tables, without a join operator. The result will be all the combinations of employees with orders, which explains the 7479 rows. This can escalate quickly.

As a side remark: This is valid SQL, but when I encounter this in a code review, it will make me suspicious. One way to make clean that you want all these combinations is the CROSS JOIN operator:

select count(*) from [HR].[Employees] cross join [Sales].[Orders]

This will be handled exactly the same as query 3, but now I know that this is on purpose.

Once we know which data we are talking about, we can then filter using the <row predicates> in the where clause. This will make sure that soon in the process, the number of rows is limited. In most join operators, there is a condition (inner join T1 on <join condition>) which would be applied here, again limiting the number of rows.

select count(*)

from [HR].[Employees] E

inner join [Sales].[Orders] O on E.empid = O.empid

The predicate E.empid = O.empid will make sure that only the relevant combinations are returned.

If there is a group by clause, that happens next, followed by the filtering on aggregated values.

Then finally SQL looks at the <field list> to determine which fields / expressions / aggregates to make available, and then the order by clause is applied.

Of Course, This is All Just A Mental Picture

Imagine a join between 3 tables, each containing 1000 rows. The resulting virtual table would contain 1.000.000.000 rows, on which SQL would have then to select the right ones. Through the use of indexes, SQL Server will only obtain the relevant row combinations. Each DBMS (Database Management System) contains a query optimizer that will intelligently use indexes to obtain the rows in the <table list>, combined with the <row predicate> from the where condition, and so on. So, if the right indexes are created in the database, only the necessary data pages will be retrieved.

Inner Queries

The table list can also contain the result of another SQL statement. The following is a useless example of this:

select count(*)

from (select * from [HR].[Employees]) E

This example will first create a virtual table named E as the result of the inner query, and use this table to select from. We can now use E as a normal table, that can be joined with other tables (or inner queries).

Tip: It is mandatory to give the inner select statement an alias, otherwise it will be impossible to work with it. Even if this is the only data source that you use, an alias is still needed.

As an example, I want to know the details of the 3 orders that gave me the highest revenue. To start with, I first find those 3 orders:

select top 3 [orderid], [unitprice] * [qty] as LineTotal

from [Sales].[OrderDetails]

order by LineTotal desc

This gives us the 3 biggest orders:

| orderid | LineTotal |

10865 | 15810,00 |

10981 | 15810,00 |

10353 | 10540,00 |

Now I can use these results in a query like:

select *

from [Sales].[OrderDetails]

where orderid in (10865, 10981, 10353)

which will give the order details for these 3 orders, at this point in time. I can use the result of the previous query in the where condition to make the query work at any point in time:

select *

from [Sales].[OrderDetails]

where orderid in

(

select top 3 [orderid]

from [Sales].[OrderDetails]

order by [unitprice] * [qty] desc

)

This query will give me the correct results. I just had to adapt some things from the initial query because the IN clause requires a list of values, so we can only return 1 value (the [orderId]). The order by clause then needs to use the full expression. Don’t worry, no more calculations than needed will be done. Trust the optimizer!

To further evolve this query, we can now use an inner join instead of WHERE … IN. The resulting execution plan will be the same again, and the results too.

select *

from [Sales].[OrderDetails] SOD

inner join (select top 3 [orderid]

from [Sales].[OrderDetails]

order by [unitprice] * [qty] desc) SO

on SO.orderid = SOD.orderid

Common Table Expressions

With all this, we have gently worked toward CTEs. A first use would be to separate the inner query from the outer query, making the SQL statement more readable. Let’s first start with another senseless example to make the idea of CTEs more clear:

;with cte as

(

select top 3 [orderid]

from [Sales].[OrderDetails]

order by [unitprice] * [qty] desc

)

select * from cte

What this does is to create a (virtual) table called cte, that can then be used in the following query as a normal data source.

Tip: The semicolon at the front of the statement is not needed if you just execute this statement. If the “with” statement follows another SQL statement, then both must be separated by a semicolon. Putting the semicolon in front of the CTE makes sure you never have to search for this problem.

The CTE is NOT a temporary table that you can use. It is part of the statement that it belongs to, and it is local to that statement. So later in the script, you can’t refer to the CTE table again. Given that the CTE is part of this statement, the optimizer will use the whole statement to make an efficient execution plan. SQL is a declarative language: you define WHAT you want, and the optimizer decides HOW to do this. The CTE will not necessarily be executed as first, it will depend on the query plan.

Let’s make this example more useful:

;with cte as

(

select top 3 [orderid]

from [Sales].[OrderDetails]

order by [unitprice] * [qty] desc

)

select *

from [Sales].[OrderDetails] SOD

inner join cte on SOD.orderid = cte.orderid

Now, for us humans, we have split the query in 2 parts: we first calculate the 3 best orders, then we use the results of that to select their order details. Like this, we can show the intent of our query.

In this case, we use the CTE only once, but if you would use it multiple times in this query, it would become more useful.

Hierarchical Queries

In this table, we see a field empid, and a field mgrid. (Almost) every employee has a manager, who can have a manager… So clearly, we have a recursive structure.

This kind of structure often occurs with:

- compositions

- Categories with an unlimited level of subcategories

- Folder structures

- etc.

So let’s see how things are organized:

select [empid], [firstname], [title], [mgrid]

from [HR].[Employees]

Gives us the following 9 rows:

We can see here that Don Funk has Sara Davis as a manager.

If we want to make this more apparent, we can join the Employees table with itself to obtain the manager info (self-join):

select E.[empid], E.[lastname], E.[firstname],

E.[title], E.[mgrid],

M.[empid], M.[lastname], M.[firstname]

from [HR].[Employees] E

left join [HR].[Employees] M on E.mgrid = M.empid

Notice that a LEFT join operator is needed because otherwise the CEO (who doesn’t have a manager) would be excluded.

We could continue this with another level until the end of the hierarchy. But if a new level is added, or a level is removed, this query wouldn’t be correct anymore. So let’s use a hierarchical CTE:

;with cte_Emp as

(

select [empid], [lastname] as lname, [firstname], [title],

[mgrid], 0 as [level]

from [HR].[Employees]

where [mgrid] is null

union all

select E.[empid], E.[lastname], E.[firstname], E.[title],

E.[mgrid], [level] + 1

from [HR].[Employees] E

inner join cte_Emp M on E.mgrid = M.empid

)

select *

from cte_Emp

I’ll first give the result before explaining what is going on:

As explained before, we start with a semicolon, to avoid frustrations later.

We then obtain the highest level of the hierarchy:

select [empid], [lastname], [firstname], [title],

[mgrid], 0 as [level]

from [HR].[Employees]

where [mgrid] is null

This is our starting point for the recursion. Using UNION ALL, we now obtain all the employees that have Sara as a manager. This is added to our result set, and then for each row that is added, we do the same, effectively implementing the recursion.

To make this more visual, I added the [level] field, so you can see how things are executed. Row 1 has level 0, because this is the part of the query (0 as [level]). The for each part in the recursive part, the level is incremented. This explains perfectly how this query is executed.

Conclusion

Common Table Expressions are one of the more advanced query mechanisms in T-SQL. They can make your queries more readable, or perform queries that would otherwise be impossible, such as outputting a hierarchical list. In this case, the real power is that a CTE can reference itself, making it possible to handle recursive structures.

Reference