Why use Vanilla JS instead of any number of the frameworks available or even TypeScript? The answer is largely irrelevant if a choice has already been made. However, deciding to replace JavaScript with some alternative for all use cases is an absolutism missing the mark. This article will describe the use of Vanilla JS leaving the choice of what language to use up to you.

Class Definitions & Namespaces

ES6 classes are not yet fully supported in the browser. Many of the limitations mentioned in this article are most relevant when developing with ES5 – such as developing for Internet Explorer or other antiquated browsers. Even without full support of classes, a similar effect can be achieved in JavaScript and it is actually quite easy to do!

We first want to make sure that the class definition is contained. This means it should not pollute the global namespace with methods and variables. This can be accomplished by using a closure – a specific one called an IIFE.

(function (global) {

"use strict";

global.API = new MyObject();

function MyObject() {

var self = this;

... var privateVariable ...

... function privateMethod() ...

... self.publicMethod ...

}

})((1,eval)('this'));

Notice that the global namespace is passed to the IIFE – since they are just methods, they can be used as such! If you want to know more about how the global namespace is obtained, check out this enlightening StackOverflow post: (1,eval)(‘this’) vs eval(‘this’) in JavaScript?

“Use Strict”

"use strict";

The class can be initialized and stored at global scope such as inside a single app-specific namespace:

(function (global,app,http) {

"use strict";

global[app] = global[app] || {};

global[app][http] = new Http();

function Http() {

var self = this;

}

})((1,eval)('this'),'App','http');

I find it easier to write client-side JavaScript as an API. Leveraging the design patterns this encourages offers many benefits to code quality and maintenance. In the code above, an instance of Http is assigned to the http property in the global.App namespace. Certainly, this should contain our methods for making HTTP calls! Code organization is one of the best things about approaching the application’s client-side JavaScript in this way. Usually, the constructor function, not an instance, would be stored – which allows certain SOLID principles to be applied.

The Constructor Function

The Http function is a special kind – a constructor function. This means an instance can be created using the new operator with the constructor function call.

function MyObject() {

}

var instance = new MyObject();

This should look familiar if you have ever created an instance in Object-Oriented code before.

Capturing this

The fact this isn’t always the same is both the power and the curse of JavaScript. The first line of the Http constructor function is capturing this in a specific context to help overcome the curse, and leverage the power:

function Http() {

var self = this;

...

}

At the scope of the constructor function, this refers to the Http object. A private variable is declared and initialized to capture it and make it available to all public and private members of Http – no matter what this happens to be during the invocation of those members. Capturing this only once and at the scope of the corresponding constructor function will reduce the possibility of this fulfilling its curse!

private Members

The variables and functions created at the scope of the Http constructor function will be available to all public and private members within the Http object.

function Http() {

var self = this,

eventHandlers = {};

function addEventHandler(event, handler) { }

function removeEventHandler(event, handler) { }

}

In this case, self, eventHandlers, and the add/remove event handler functions are private members of Http. They are not accessible to external sources – only public and private members of Http can access Http‘s private members.

public Members

The properties and methods exposed on the Http object, such as those existing in the prototype chain, that can be accessed from external sources, are considered public.

function Http() {

var self = this;

self.get = function (request) { ...

self.post = function (request, data) { ...

}

Add public members to the self variable within the constructor function. This allows other code to perform the operations of an Http instance.

static Members

Members can be static as well. By declaring a variable on the constructor function itself, it can be assigned a value, instance, or function that is public while not depending on an instance to be created using the constructor function:

function Http() {

}

Http.setup = function () { ...

The static Http member can be used without creating an Http instance:

Http.setup();

The member is public and available anywhere the Http constructor function is available.

Execution Contexts

Without going into the depths of execution contexts in JavaScript, there are a few things to note. This section will describe a couple different execution contexts and integration points at which JavaScript code is executed.

Global Context

There is only 1 global context – or global scope or global namespace. Any variable defined outside a function exists within the global context:

var x = 9;

function XManager() {

var self = this;

self.getX = function () { return x; }

self.setX = function (value) { x = value; }

}

The global-scoped x variable is defined outside of the XManager function and assigned the value of 9. When getX is called, it will return the global-scoped x (the value of 9).

Local Scope – Function Execution Context

The alternative to the Global Scope is Local Scope. The local scope is defined by the function execution context:

var x = 9;

function XManager() {

var self = this,

x = 10;

...

self.getInstanceX = function () {

return x;

}

}

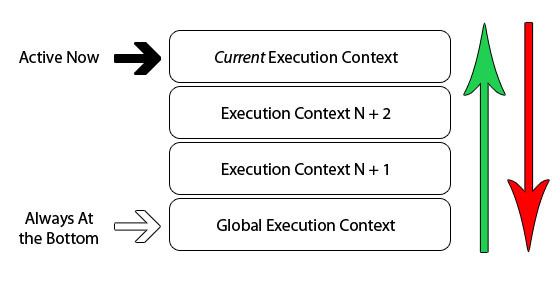

In this case, a variable x is declared twice. The first time is within the global execution context. This variable is accessible within XManager. Within the XManager constructor function, the private variable x is declared and initialized to 10. The getInstanceX method will return the variable x that is first in its execution context stack:

The getInstanceX method is “Active Now”, XManager‘s private variable x is next, followed by the global-scoped variable x, and finally the global execution context. All of this is to explain why getInstanceX returns 10 and not 9. Powerful stuff!

let & Block-Level Scope

I cannot discuss execution contexts without mentioning the keyword let. This keyword allows the declaration of block-level scope variables. Like ES6 classes, if antiquated browsers need to be supported, the let keyword will not be available.

function Start() {

let x = 9;

function XManager() {

let x = 10;

function getX() {

console.log(x);

}

console.log(x);

getX();

}

console.log(x);

XManager();

}

Start();

A block scope variable is accessible within its context (Start) and contained sub-blocks (XManager). The main difference from var is that the scope of var is the entire enclosing function. This means, when using let, XManager and the contained sub-blocks (getX) have access to the new variable x assigned to the value of 10 while the variable x in the context of Start will still have the value of 9.

Event Handlers

Client-side JavaScript code is triggered by the user through DOM events as they interact with rendered HTML. When an event is triggered, its subscribers (read event handlers) will be called to handle the event.

HTML – Event Subscription

<span id="mce_SELREST_start" style="overflow:hidden;line-height:0;"></span>

<div id="submit">Button</div>

JAVASCRIPT – Event Subscription

var button = document.getElementById("submit");

button.addEventHandler('click', clickHandler);

JAVASCRIPT – Event Handler

function clickHandler() {

console.log("Click event handled!");

}

Event handling marks the integration point between user interaction with HTML and the application API in JavaScript.

Understanding how to create objects and the Execution Context is important when writing client-side JavaScript. Designing the JavaScript as an API will help to further manage the pros and cons of the language.

CodeProject