The post “Azure Functions and Serverless Computing” appeared first on MSDN Azure Development Community.

In my previous blog post, WebJobs in Azure with .NET Core 2.1, I briefly mentioned Azure Functions. Azure Functions are usually small (or somewhat larger) bits of code that run in Azure and are triggered by some event. Azure takes complete care of the entire infrastructure of your Functions making it a so-called serverless solution. The only thing you need to worry about is your code.

The code samples for this post can be found on my GitHub profile. You shouldn’t really need it because I’m only using default templates, but I’ve included them because I needed them in source control for CI/CD anyway.

Serverless Computing

Before we get into Azure Functions, I’d like to explain a bit about serverless computing. Serverless computing isn’t completely serverless, your code still needs somewhere to run after all. However, the servers are completely managed by your cloud provider, which is Azure in our case.

With most App Services, like a Web App or an API App, you need an App Service Plan, which is basically a server that has x CPU cores and y memory. While you can run your Functions on an App Service Plan, it’s far more interesting to run them in a so-called “Consumption Plan”. With a consumption plan, your resources are completely dynamic, meaning you’re only actually using a server when your code is running.

It’s Cheap

Let me repeat that, you’re only actually using a server when your code is running. This may seem trivial, but has some huge implications! With an App Service Plan, you always have a server even when no code is running. This means you pay a monthly fee just to keep the server up and running. See where this is heading? That’s right, with a consumption plan you pay only when your code is running because that’s the only time you’re actually using resources!

There’s a pretty complicated formula using running time, memory usage and executions, but believe me, Functions are cheap. Your first million executions and 400,000 GB/sec (whatever that means) are free. Microsoft has a pricing example which just verifies that it’s cheap.

It’s Dynamic

Price is cool, but we ain’t cheap! Probably the coolest feature about Functions is that Azure scales servers up and down depending on how busy your function is. So let’s say you’re doing some heavy computing which takes a while to run and is pretty resource intensive, but you need to do that 100 times in parallel… Azure just spins up some extra servers dynamically (and, of course, you pay x times more, but that’s still pretty cheap). When your calculations are complete, your servers are released and you stop paying. There is a limit to this behavior. Azure will spin up a maximum of 200 server instances per Function App and a new instance will only be allocated at most once every 10 seconds. One instance can still handle multiple executions though, so 200 servers usually does not mean 200 concurrent executions.

That said, you can’t really configure a dynamically created server. You’ll have to trust Microsoft that they’re going to temporarily give you a server that meets your needs. And, as you can guess, those needs better be limited. Basically, your need should be that your language environment, such as the .NET Framework (or .NET Core) for C#, is present. One cool thing though, next to C#, functions can be written in F# and JavaScript, and Java is coming in v2. There are some other languages that are currently running in v2, like Python, PHP, and TypeScript, but it looks like Microsoft isn’t planning on fully supporting these languages in the near future.

Azure Functions in the Azure Portal

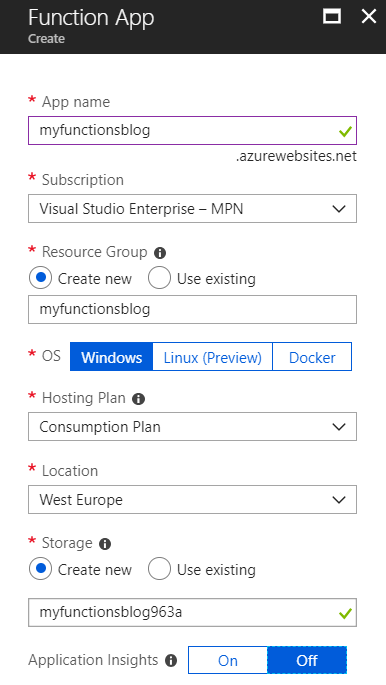

Let’s create our first Azure Functions. Go to App Services and create a new one. When you create an App Service, you should get an option to create a Function App (next to Web App, API App, etc.). The creation screen looks pretty much the same as for a regular web app, except that Function Apps have a Consumption Plan as a Hosting Plan (which you should take) and you get the option to create a Storage Account, which is needed for Azure to store your Functions.

Create a new Function App

This will create a new Function App, a new Hosting Plan, and a new Storage Account. Once Azure created your resources look up your Function Apps in your Azure resources. You should see your version of “myfunctionsblog” (which should be a unique name). Now, hover over “Functions” and click the big plus to add a Function.

Azure Functions

In the next form, you can pick a scenario. Our options are “Webhook + API”, “Timer” or “Data processing”. You can also pick a language, “CSharp”, “JavaScript”, “FSharp” or “Java”. Leave the defaults, which are “Webhook + API” and “CSharp” and click the “Create this function” button.

Editing and Running Your Azure Functions

You now get your function, which is a default template. You can simply run it directly in the Azure portal and you can see a log window, errors and warnings, a console, as well as the request and response bodies. It’s like a very lightweight IDE in Azure right there. I’m not going over the actual code because it’s pretty basic stuff. You can play around with it if you like.

Next to the “Save” and “Run” buttons, you see a “</> Get function URL” link. Click it to get the URL to your current function. There are one or more function keys, which give access to just this function); there are one or more host keys, which give access to all functions in the current host; and there’s a master key, which you should never share with third parties. You can manage your keys from the “Manage” item in the menu on the left (with your Functions, Proxies, and Slots).

Consuming Azure Functions

The Function we created is HTTP triggered, meaning we must do an HTTP call ourselves. You can, of course, use a client such as Postman or SoapUI, but let’s look at some C# code to consume our Function. Create a (.NET Core) Console App in Visual Studio (or use my example from GitHub) and paste the following code in Program.cs.

using System;

using System.Net.Http;

namespace ConsoleApp1

{

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

using (var client = new HttpClient())

{

string url = "https://myfunctionsblog.azurewebsites.net/api/

HttpTriggerCSharp1?code=CJnVDV8gELVapT7gNoMexKLI1j7zFNX6FJBOP7lMBC71vkvuAT9J4A==";

var content = new StringContent("{\"name\": \"Function\"}",

Encoding.UTF8, "application/json");

client.PostAsync(url, content).ContinueWith(async t =>

{

var result = await t.Result.Content.ReadAsStringAsync();

Console.WriteLine("The Function result is:");

Console.WriteLine(result);

Console.WriteLine("Press any key to exit.");

Console.ReadKey();

}).Wait();

}

}

}

}

If your Function returns an error (for whatever reason), your best logging tool is Application Insights, but that is not in the scope of this blog post.

Of course, if you have a function that’s triggered by a timer or a queue or something else, you don’t need to trigger it manually.

Azure Functions in Visual Studio 2017

Creating a Function in the Azure Portal is cool, but we want an IDE, source control, and CI/CD. So open up VS2017 and look for the “Azure Functions” template (under Visual C# -> Cloud). You can choose between “Azure Functions v1 (.NET Framework)” and “Azure Functions v2 Preview (.NET Standard)”. We like .NET Standard (which is the common denominator between the .NET Framework, .NET Core, UWP, Mono, and Xamarin) so we pick the v2 Preview.

Again, go with the HTTP trigger and find your Storage Account. Leave the access rights on “Function”. The generated function template is a little bit different than the one generated in the Azure portal, but the result is the same. One thing to note here is that Functions actually use the Microsoft.Azure.WebJobs namespace for triggers, which once again shows the two can (sometimes) be interchanged.

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Http;

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Mvc;

using Microsoft.Azure.WebJobs;

using Microsoft.Azure.WebJobs.Extensions.Http;

using Microsoft.Extensions.Logging;

using Newtonsoft.Json;

using System.IO;

namespace FunctionApp

{

public static class Function1

{

[FunctionName("Function1")]

public static IActionResult Run([HttpTrigger

(AuthorizationLevel.Function, "get", "post", Route = null)]HttpRequest req, ILogger log)

{

log.LogInformation("C# HTTP trigger function processed a request.");

string name = req.Query["name"];

string requestBody = new StreamReader(req.Body).ReadToEnd();

dynamic data = JsonConvert.DeserializeObject(requestBody);

name = name ?? data?.name;

return name != null

? (ActionResult)new OkObjectResult($"Hello, {name}")

: new BadRequestObjectResult("Please pass a name on the query string

or in the request body");

}

}

}

>

When you run the template, you get a console which shows the Azure Functions logo in some nice ASCII art as well as some startup logging. Windows Defender might ask you to allow access for Functions to run, which you should grant.

Now if you run the Console App we created in the previous section and change the functions URL to “http://localhost:7071/api/Function1” (port may vary), you should get the same result as before.

Deployment Using Visual Studio

If you’ve read my previous blog posts, you should be pretty familiar with this step. Right-click on your Functions project and select “Publish…” from the menu. Select “Select Existing” and enable “Run from ZIP (recommended)”. Deploying from ZIP will put your Function in a read-only state, but it most closely matches your release using CI/CD. Besides, all changes should be made in VS2017 so they’re in source control. In the next form, find your Azure App and deploy to Azure.

If you’ve selected Azure Functions v2 earlier, you’ll probably get a dialog telling you to update your Functions SDK on Azure. A little warning here, this could mess up already existing functions (in fact, it simply deleted my previous function). As far as I understand, this only affects your current Function App, but still use at your own risk.

Once again, find your Functions URL, paste it in the Console App, and check if you get the desired output.

Deployment using VSTS

Now for the good parts, Continuous Integration and Deployment. Open up Visual Studio Team Services and create a new build pipeline. You can pick the default .NET Core template for your pipeline, but you should change the “Publish” task so it publishes “**/FunctionApp.csproj” and not “Publish Web Projects”. You can optionally enable continuous integration in the “Triggers” tab. Once you’re done, you can save and queue a build.

The next step is to create a new release pipeline. Select the Azure “App Service deployment” template. Change the name of your pipeline to something obvious, like “Function App CD”. You must now first add your artifact and you may want to enable the continuous deployment trigger. You can also rename your environment to “Dev” or something.

Next, you need to fill out some parameters in your environment tasks. The first thing you need to set is your Azure subscription and authorize it. For “App type”, pick the “Function App”. If you’ve successfully authorized your subscription, you can select your App Service name from the drop-down. Also, and this one is a little tricky, in your “Azure App Service Deploy” task, disable “Take App Offline” which is hidden under the “Additional Deployment Options”. Once you’re done, and the build is finished, create a new release.

When all goes well, test your changes with the Console App.

If everything works as expected, try changing the output of your Function App, push it to source control, and see your build and release pipelines do their jobs. Once again, test the change with your Console App.

Working Around Some Bugs

So… A header that mentions bugs and workarounds is never a good thing. For some reason, my release kept failing due to an “invalid access to memory location”. Probably because I had already deployed the app using VS2017. I also couldn’t delete my function because the trash can icon was disabled. Google revealed I wasn’t the only one with that problem. So anyway, I am currently using a preview of Azure Functions v2 and I’m sure Microsoft will figure this stuff out before it goes out of preview.

Here’s the deal, you probably have to delete your Function App completely (you can still delete it through your App Services). Recreate it, go to your Function App (not the function itself, but the app hosting it, also see the next section on “Additional settings”), and find the “Function app settings”. Over here you can find a switch “~1” and “beta” (which are v1 and v2 respectively). Set it on “beta” here. Now deploy using VSTS. Publishing from VSTS will cause your release to fail again.

Bottom line: Don’t use VS2017 to deploy your Function App!

Additional Settings

There’s just one more thing I’d like to point out to you. While Azure Functions look different from regular Web Apps and Web APIs, they’re still App Services with a Hosting Plan. If you click on your Function App, you land on an “Overview” page. From here, you can go to your Function app settings (which includes the keys) and your Application settings (which look a lot like Web App settings). You’ll find your Application settings, like “APPINSIGHTS_INSTRUMENTATIONKEY”, “AzureWebJobsDashboard”, “AzureWebJobsStorage” and “FUNCTIONS_EXTENSIONS_VERSION”.

Another tab is the “Platform features” tab, which has properties, settings and code deployment options (see my post Azure Deployment using Visual Studio Team Services (VSTS) and .NET Core for more information on deployment options).

Functions Platform features

Wrap Up

Azure Functions are pretty cool and I can’t wait for v2 to get out of preview and fully support .NET Standard as well as fix the bugs I mentioned. Now, while Functions may solve some issues, like dynamic scaling, it may introduce some problems as well.

It is possible to create a complete web app using only Azure Functions. Whether you’d want that is another question. Maybe you’ve heard of micro-services. Well, with Functions, think nano-services. A nano-service is often seen as an anti-pattern where the overhead of maintaining a piece of code outweighs the code’s utility. Still, when used wisely, and what’s wise is up to you, Functions can be a powerful, serverless, asset to your toolbox. If you want to know more about the concepts of serverless computing, I recommend a blog post by my good friend Sander Knape, who wrote about the AWS equivalent, AWS Lambda, The hidden challenges of Serverless: from VM to function.

Don’t forget to delete your resources if you’re not using them anymore or your credit card will be charged.

Happy coding!

The post Azure Functions and Serverless Computing appeared first on Sander Rossel.