Introduction

This article is about HTML and JavaScript injection techniques used to exploit web site vulnerabilities. Nowadays, it's not usual to find a completely vulnerable site to this type of attacks, but only one is enough to exploit it. I'll make a compilation of these techniques all together, in order to facilitate the reading and to make it entertaining. HTML injection is a type of attack focused upon the way HTML content is generated and interpreted by browsers at client side. Otherwise, JavaScript is a widely used technology in dynamic web sites, so the use of techniques based on this, like injection, complements the nomenclature of 'code injection'.

Code Injection

This type of attack is possible by the way the client browser has the ability to interpret scripts embedded within HTML content enabled by default, so if an attacker embeds script tags such <SCRIPT>, <OBJECT>, <APPLET>, or <EMBED> into a web site, the web browser's JavaScript engine will execute it. Typical targets of this type of injection are forums, guestbooks, or whatever section where the administrator allows the insertion of text comments; if the design of the web site isn't parsing the comments inserted, and takes '<' or '>' as real chars, a malicious user could type:

I like this site because <script>alert('Injected!');</script> teaches me a lot

If it works and you can see the message box, the door is opened to the attacker's imagination limits! A common code insertion used to drive navigation to another website is something like this:

<H1> Vulnerability test </H1>

<META HTTP-EQUIV="refresh" CONTENT="1;url=http://www.test.com">

Same within a <FK> or <LI> tag:

<FK STYLE="behavior: url(http://<<Other website>>;">

Other tags used to execute malicious JavaScript code are, for example, <BR>, <DIV>, even background-image:

<BR SIZE="&{alert('Injected')}">

<DIV STYLE="background-image: url(javascript:alert('Injected'))">

The <TITLE> tag is a common weak point if it's generated dynamically. For example, suppose this situation:

<HTML>

<HEAD>

<TITLE><?php echo $_GET['titulo']; ?>

</TITLE>

</HEAD>

<BODY>

...

</BODY>

</HTML>

If you build title as 'example </title></head><body><img src=http://myImage.png>', HTML resulting would insert the 'myImage.png' image first of all:

<HTML>

<HEAD>

<TITLE>example</title></head><body><img src=http://myImage.png></TITLE>

</HEAD>

<BODY>

...

</BODY>

</HTML>

There is another dangerous HTML tag that could exploit a web browser's frames support characteristic: <IFRAME>. This tag allows (within Sandbox security layer) cross-scripting exploiting using web browser elements (address bar or bookmarks, for example), but this theme is outside the scope of this article.

Otherwise, there is a common technique widely known as "in-line" code injection. This technique exploits the JavaScript functions "alert" and "void". Testing it is very easy, just navigate to whatever site, and type in the web browser's address bar:

javascript:alert('Executed!');

This is not a harmful script, as you can see, but suppose you want to get information about the site, for example, if it is using cookies or not, you could type something like this :

javascript:alert(document.cookie);

If the website is not using cookies, no problem, but else, you could read values like the server session ID, or any user data stored in cookies by the application.

Suppose now that we use the void() JavaScript function instead of alert(). This function returns a null value to the web browser, so no recharging page action is executed. We could change the DOM values inside this function and no navigation change state would occur. Imagine you've found a site that stores the PHP session ID in the common cookie 'PHPSESSID'; if we start a new navigation to the same website in another web browser instance, we'll get a new 'PHPSESSID'; we could change the session IDs in both instances by typing:

javascript: void(document.cookie="PHPSESSID = <<Any other session ID>>");

alert(document.cookie);

(The code above was wrapped to avoid scrolling)

You will see in the message box the new session ID assigned to the actual one. This example also shows the possibility of concatenating more than one action in the same line of execution.

By only taking a look at site cookies, you could find some very descriptive ones implementing security features; for example, if you find a site cookie like "logged=no", probably you could go into the logged area simply by changing that cookie value:

javascript: void(document.cookie="logged=yes");

Following this line, it's possible to modify any DOM object using JavaScript and inject it using the previous techniques. Analyzing the source code of a web page, you may find it uses forms (<FORM>) for different purposes; in this case, you could change any form field value using the void() function, too. Imagine a shopping portal with a shopping cart; if the site designer didn't take care of this type of injection, you could fill the cart and pay for it only $1:

javascript:void(document.forms[0].total.value=1);

These other techniques are named indirect code injection; not only cookies or forms modification are exploited by this technique, any DOM component or HTTP header is exposed.

So, it's very important to keep in mind these code injection techniques when developing web applications to make it a more safe application.

Preventing Code Injection

When developing web applications, it's very recommendable to follow the next considerations to prevent possible code injection:

- Do not rely on client-side JavaScript validation whenever possible; as shown before, this is easily deceived using "in-line" injection. For example, suppose you have a shopping portal where you rely the price of each item at the client side.

Suppose you have only one form to store the shopping chart; attackers could modify your bill, simply by changing the price as seen before:

javascript:void(document.forms[0].price.value=1);

A solution to this situation is just maintaining the shopping chart actions on the server side, and getting the client side refreshed via AJAX, for example.

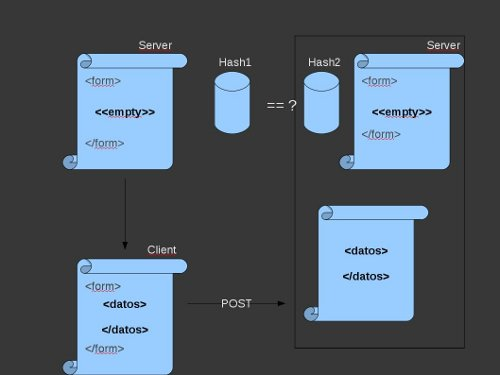

Don't store sensible data into cookies, because they can be easily modified by an attacker, as seen before. If you need to store data in cookies, store them with a hash signature generated with a server side key.Never use hidden boxes to hold items because they can be hard coded into the code. Otherwise, you should always validate the fields at server side using a secure algorithm, with data received from the client as input:

Like the <TITLE> example above, you better not use dynamic DOM element generation.Take care about dynamic evaluation vulnerabilities (like the <TITLE> example above). Imagine this piece of code in a PHP page:

$dato = $_GET['formAge'];

eval('$edad = ' . $dato . ';');

eval() parameters will be processed, so if "formAge" is set to "5; system('/bin/rm -rf *')", additional code will be executed on the server and will remove all the files. Dangerous, don't you think so?

If you are developing a web site that allows the user to upload content (forum, guestbook, "contact me", etc.), you may split special HTML chars, so injected tags will be maintained in the website, but will not be executed; you can get this with the strip_tags() PHP function, htmlentities(), urlencode(), or htmlspecialchars(), for example.Use an SSL certificate for sensible operations; this doesn't avoid JavaScript injection, but avoids sensible data from being read by anyone else.

Ultimately, the best defense to code injection attacks resides on "Best practices" while programming.

Points of Interest

Implementing security features in web applications sometimes takes no care by programmers, and exposes the project to attackers.

History

- 1.0 - 05/12/2010 - Original version.