Contents

Autofac is an open-source dependency injection (DI) or inversion of control (IoC) container developed on Google Code.

Autofac differs from many related technologies in that it sticks as close to bare-metal C# programming as possible. It is designed around the premise that it is wasteful to work in such a powerful language as C# but to lose that power to purely reflection-based APIs like those prevalent in the other .NET containers.

The result is that Autofac supports a wide array of application designs with very little additional infrastructure or integration code, and with a lower learning curve.

That is not to say that it is simplistic; it has most of the features offered by other DI containers, and many subtle features that help with the configuration of your application, managing components' life-cycles, and keeping the dependencies under control.

This article uses an example to demonstrate the most basic techniques for creating and wiring together application components, then goes on to discuss the most important features of Autofac.

If you're already using a DI container and want to get a feel for how Autofac is different, you may wish to skip ahead briefly and check out the code in the Autofac in Applications section.

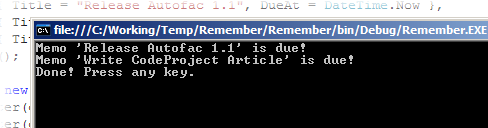

The application is a console program that checks a list of memos, each with a due date, and notifies the user of the ones that are overdue.

A lot of simplifications have been made in the example code. In the interests of brevity, XML comments, argument checking, and exception handling are elided from all of the code samples.

At the core of the application is the MemoChecker component, which looks like this:

class MemoChecker

{

IQueryable<Memo> _memos;

IMemoDueNotifier _notifier;

public MemoChecker(IQueryable<Memo> memos, IMemoDueNotifier notifier)

{

_memos = memos;

_notifier = notifier;

}

public void CheckNow()

{

var overdueMemos = _memos.Where(memo => memo.DueAt < DateTime.Now);

foreach (var memo in overdueMemos)

_notifier.MemoIsDue(memo);

}

}

The following aspects of this class come as a direct result of using a dependency-injected style:

- It accepts all of its dependencies as parameters, in this case to the constructor

- It is independent of persistence – the

IQueryable that holds the memos might be backed by a database table, a structured file, or an in-memory collection - It is independent of how the user is notified – the notifier could send an email, write to the event log, or print to the console

These things make the class more easily testable, configurable and maintainable.

The IMemoDueNotifier interface has a single method, MemoIsDue(), which is implemented by another dependency-injected component called PrintingNotifier:

class PrintingNotifier : IMemoDueNotifier

{

TextWriter _writer;

public PrintingNotifier(TextWriter writer)

{

_writer = writer;

}

public void MemoIsDue(Memo memo)

{

_writer.WriteLine("Memo '{0}' is due!", memo.Title);

}

}

Like MemoChecker, this class accepts its dependencies through its constructor. The TextWriter type is a standard .NET class used throughout the .NET Framework, and is the base class of things like StringWriter and System.Console.Out.

The MemoChecker gets the overdue memos from an IQueryable<Memo>. The data store used in the example is an in-memory list:

IQueryable<Memo> memos = new List<Memo>() {

new Memo { Title = "Release Autofac 1.0", DueAt = new DateTime(2007, 12, 14) },

new Memo { Title = "Write CodeProject Article", DueAt = DateTime.Now },

new Memo { Title = "Release Autofac 2.3", DueAt = new DateTime(2010, 07, 01) }

}.AsQueryable();

The IQueryable interface introduced in .NET 3.5 is suitable as a source of Memos because it can be used to query either in-memory objects or rows in a relational database.

The ultimate structure of the application looks like:

Most of this article is concerned with how a MemoChecker gets associated with its notifier and memo services, and how each of these objects in turn get 'wired up' to their own dependencies.

With only a few components, configuring a MemoChecker by hand isn't hard. In fact, it's trivial and looks like this:

var checker = new MemoChecker(memos, new PrintingNotifier(Console.Out));

checker.CheckNow();

A real application, with several layers and all sorts of components, shouldn't be configured this way. This kind of direct object creation works well locally on a few classes, but doesn't scale up to large numbers of components.

For one thing, the code that did this at startup would get increasingly complex over time, and would potentially need to be reorganized every time the dependencies of a class change.

More importantly, it is hard to switch the implementations of services; e.g., an EmailNotifier could be substituted for the printing notifier, but this itself will have dependencies that may be different from those of the PrintingNotifier, yet may intersect with the dependencies of other components. (This is the problem of composability, and is worth an article in itself.)

Autofac and other dependency injection containers circumvent these issues by 'flattening out' the deeply-nested structure of the object graph at configuration-time...

When using Autofac, accessing the MemoChecker is separate from creating it:

container.Resolve<MemoChecker>().CheckNow();

The container.Resolve() call requests an instance of MemoChecker that's set up and ready to use. So, how does the container work out how to create a MemoChecker?

A dependency injection container is a collection of registrations that map services to components. A service, in this context, is a way of identifying a particular functional capability – it could be a textual name, but is more often an interface type.

A registration captures the dynamic behaviour of the component within the system. The most noticeable aspect of this is the way in which instances of the component are created.

Autofac can accept registrations that create components using expressions, provided instances, or with Reflection based on System.Type.

The following sets up a registration for the MemoChecker component:

builder.Register(c => new MemoChecker(c.Resolve<IQueryable<Memo>>(),

c.Resolve<IMemoDueNotifier>()));

Each Register() statement deals with only one part of the final object graph and its relationship to its direct dependencies.

The lambda expression c => new MemoChecker(...) will be used by the container to create the MemoChecker component.

Each MemoChecker depends upon two additional services, IQueryable<Memo> and IMemoDueNotifier. These are retrieved inside the lambda expression by calling the Resolve() method on the container, which is passed in as the parameter c.

The registration doesn't say anything about which components will implement IQueryable<Memo> or IMemoDueNotifier – these two services are configured independently in the same way that MemoChecker is.

The expression being provided to Register() has a return type of MemoChecker, so Autofac will use this as the default service for this registration unless another is specified with the As() method. The As() call can be included for the sake of being more explicit:

builder.Register(c => new MemoChecker(...)).As<MemoChecker>();

Either way, a request for MemoChecker from the container will now result in a call to our expression.

Autofac won't execute the expression when the component is registered. Instead, it will wait until Resolve<MemoChecker>() is called. This is important, because it eliminates one point of reliance on the order in which components are registered.

The IQueryable<Memo> service is provided by the existing memos instance, and the PrintingMemoNotifier class is eventually wired up to the TextWriter instance Console.Out:

builder.RegisterInstance(memos);

builder.RegisterInstance(Console.Out).As<TextWriter>().ExternallyOwned();

The memos and Console.Out are provided to the container as instances that are already created. (For an explanation of ExternallyOwned(), see Deterministic Disposal.)

Autofac can also create components the way that other containers do, using reflection (many optimise this scenario with MSIL-generation.)

This means that you can tell Autofac about the type that provides a service, and it will work out how to call the most appropriate constructor, with parameters chosen according to the other available services.

The MemoChecker registration could have been replaced with:

builder.RegisterType<MemoChecker>();

In general, the most common use of auto-wiring is to register a batch of components, e.g.:

foreach (Type t in Assembly.GetExecutingAssembly().GetTypes())

if (typeof(IController).IsAssignableFrom(t))

builder.Register(t);

This makes large numbers of components available without the overhead of registering each one, and you should definitely consider it in these situations. Autofac provides shortcuts for registering batches of components this way:

builder.RegisterAssemblyTypes(Assembly.GetExecutingAssembly())

.As<IController>();

Auto-wiring is also very useful when components are registered via the application's XML configuration file.

The process of creating the component registrations before requesting the MemoChecker service from the container is shown below:

var builder = new ContainerBuilder();

builder.Register(c => new

MemoChecker(c.Resolve<IQueryable<Memo>>(),

c.Resolve<IMemoDueNotifier>()));

builder.Register(c => new

PrintingNotifier(c.Resolve<TextWriter>())).As<IMemoDueNotifier>();

builder.RegisterInstance(memos);

builder.RegisterInstance(Console.Out).As<TextWriter>().ExternallyOwned();

using (var container = builder.Build())

{

container.Resolve<MemoChecker>().CheckNow();

}

The lack of nesting in the configuration code demonstrates the 'flattening out' of the dependency structure that a container provides.

It may be hard to see how this could ever be simpler than the direct object construction in the 'by hand' example, but again remember that this sample application has far fewer components than most useful systems.

The most important difference to note is that each component is now configured independently of all the others. As more components are added to the system, they can be understood purely in terms of the services they expose and the services they require. This is one effective means of controlling architectural complexity.

IDisposable is both a blessing and a curse. It's great to have a consistent way of communicating that a component should be cleaned up. Unfortunately, which component should do this cleanup, and when, is not always easy to determine.

The problem is made worse by designs that allow for multiple implementations of the same service. In the example application, it is feasible that many different implementations of IMemoDueNotifier may be deployed. Some of these will be created in a factory, some will be singletons, some will need disposal, and some will not.

Components that use a notifier have no way of knowing whether they should try to cast it to IDisposable and call Dispose() or not. The kind of bookkeeping that results is both error-prone and tedious.

Autofac solves this problem by tracking all of the disposable objects created by the container. Note the example from above:

using (var container = builder.Build())

{

container.Resolve<MemoChecker>().CheckNow();

}

The container is in a using block because it takes ownership of all of the components that it creates, and disposes off them when it is itself disposed.

This is important because true to the spirit of separating usage from configuration concerns, the MemoChecker service can be used wherever necessary – even created indirectly as a dependency of another component – without worrying as to whether or not it should be cleaned up.

With this comes peace of mind – you don't even need to read back through the example to discover whether any of the classes in it actually implemented IDisposable (they don't) because you can rely on the container to do the right thing.

Note the ExternallyOwned() clause added to the Console.Out registration in the complete configuration example above. This is desirable because Console.Out is disposable, yet the container shouldn't dispose off it.

The container will normally exist for the duration of an application execution, and disposing it is a good way to free resources held by components with the same application-long life-cycle. Most non-trivial programs should also free resources at other times: on completion of an HTTP request, at the exit of a worker thread, or at the end of a user's session.

Autofac helps you manage these life-cycles using nested lifetime scopes:

using (var appContainer = builder.Build())

{

using (var request1Lifetime = appContainer.BeginLifetimeScope())

{

request1Lifetime.Resolve<MyRequestHandler>().Process();

}

using (var request2Lifetime = appContainer.BeginLifetimeScope())

{

request2Lifetime.Resolve<MyRequestHandler>().Process();

}

}

Lifetime management is achieved by configuring how component instances map to lifetime scopes.

Component Lifetime

Autofac allows you to specify how many instances of a component can exist and how they will be shared between other components.

Controlling the scope of a component independently of its definition is a very important improvement over traditional methods like defining singletons through a static Instance property. This is because of a distinction between what an object is and how it is used.

The most common lifetime settings used with Autofac are:

- Single Instance

- Instance per Dependency

- Instance per Lifetime Scope

With single-instance lifetime, there will be at most one instance of the component in the container, and it will be disposed when the container in which it is registered is disposed (e.g., appContainer above).

A component can be configured to have this lifetime using the SingleInstance() modifier:

builder.Register(c => new MyClass()).SingleInstance();

Each time such a component is requested from the container, the same instance will be returned:

var a = container.Resolve<MyClass>();

var b = container.Resolve<MyClass>();

Assert.AreSame(a, b);

Instance per Dependency

When no lifetime setting is specified in a component registration, an instance-per-dependency is assumed. Each time such a component is requested from the container, a new instance will be created:

var a = container.Resolve<MyClass>();

var b = container.Resolve<MyClass>();

Assert.AreNotSame(a, b);

A component resolved this way will be disposed along with the lifetime scope from which it was requested. If a per-dependency component is required in order to construct a single-instance component, for example, then the per-dependency component will live alongside the single-instance component for the life of the container.

The final basic lifetime model is per-lifetime-scope, achieved using the InstancePerLifetimeScope() modifier:

builder.Register(c => new MyClass()).InstancePerLifetimeScope();

This provides the flexibility needed to implement per-thread, per-request, or per-transaction component life-cycles. Simply create a lifetime scope that lives for the duration of the required life-cycle. Requests from the same scope object will retrieve the same instance, while requests in different scopes will result in different instances:

var a = container.Resolve<MyClass>();

var b = container.Resolve<MyClass>();

Assert.AreSame(a, b);

var inner = container.BeginLifetimeScope();

var c = inner.Resolve<MyClass>();

Assert.AreNotSame(a, c);

A component's dependencies can only be satisfied by other components within the same scope or in an outer (parent) scope. This ensures that a component's dependencies are not disposed before it is. If a nesting of application, session, and request is desired, then the containers would be created as:

var appContainer = builder.Build();

var sessionLifetime = appContainer.BeginLifetimeScope();

var requestLifetime = sessionLifetime.BeginLifetimeScope();

var controller = requestLifetime.Resolve<IController>("home");

Keep in mind with these examples that the appContainer would have many sessionLifetime children created from it (one per session), and each session would, during its lifetime, be the parent of many requestLifetimes (one per HTTP request in the session.)

In this scenario, the allowed direction of dependencies is request -> session -> application. Components that are used in processing a user's request can reference any other component, but dependencies in the other direction are not allowed, so, for instance, an application-level single-instance component won't be wired up to a component specific to a single user's session.

In such a hierarchy, Autofac will always serve component requests in the shortest-lived lifetime. This will generally be the request lifetime. Single-instance components will naturally reside at the application-level. To pin the lifetime of a component to the session-level, see the tags article on the Autofac Wiki.

Autofac's scope model is flexible and powerful. The relationship between scope and nested lifetime disposal makes a huge number of dependency configurations possible, while enforcing that an object will always live at least as long as the objects that depend on it.

Dependency injection is an extremely powerful structuring mechanism, but to gain those advantages, a significant proportion of a system's components need to be available to other components through the container.

Normally, this presents some challenges. In the real world, existing components, frameworks, and architectures often come with their own unique 'creational' or life-cycle requirements.

The features of Autofac described so far are designed to get existing, 'plain old .NET' components into the container without the need for modifications or adapter code.

Using expressions for component registration makes including Autofac in an application a snap. A few example scenarios illustrate the kinds of things Autofac facilitates:

Existing factory methods can be exposed using expressions:

builder.Register(c => MyFactory.CreateProduct()).As<IProduct>();

Existing singletons that need to be loaded on first access can be registered using an expression, and loading will remain 'lazy':

builder.RegisterInstance(c => MySingleton.Instance);

Parameters can be passed to a component from any available source:

builder.RegisterInstance(c => new MyComponent(Settings.SomeSetting));

An implementation type can even be chosen based on a parameter:

builder.Register<CreditCard>((c, p) => {

var accountId = p.Get<string>("accountId");

if (accountId.StartsWith("9"))

return new GoldCard(accountId);

else

return new StandardCard(accountId);

});

Integration, in this context, means making the services of existing libraries and application components available through the container.

Autofac comes with support for some typical integration scenarios like usage within an ASP.NET application; however, the flexibility of the Autofac model makes a lot of integration tasks so trivial that they're best left to the designer to implement in the way most suitable for their application.

Expression-based registrations and deterministic disposal, combined with the 'laziness' of component resolution, can be surprisingly handy when integrating technologies:

var builder = new ContainerBuilder();

builder.Register(c => new ChannelFactory<ITrackListing>(new BasicHttpBinding(),

new EndpointAddress("http://localhost/Tracks")))

.As<IChannelFactory<ITrackListing>>();

builder.Register(c => c.Resolve<IChannelFactory<ITrackListing>>().CreateChannel())

.As<ITrackListing>()

.UseWcfSafeRelease();

using (var container = builder.Build())

{

var trackService = container.Resolve<ITrackListing>();

var tracks = trackService.GetTracks("The Shins", "Wincing the Night Away");

ListTracks(tracks);

}

This is an example of WCF client integration taken from the Autofac website. The two key services here are ITrackListing and IChannelFactory<ITrackListing> - these common bits of WCF plumbing are easy to fit into expression-based registrations.

Some things to note here:

- The channel factory isn't created unless it is required, but once it is created, it will be kept and reused each time

ITrackListing is requested. ITrackListing doesn't derive from IDisposable, yet in WCF, the client service proxies created this way need to be cast to IDisposable and disposed. The code using ITrackListing can remain unaware of this implementation detail.- Endpoint information can come from anywhere – another service, a database, a configuration file (with other pre-built container integrations for WCF, these decisions are made for you).

- No additional concepts other than the basic

Register() methods are used (to do this in any other container would require customised classes/facilities to be implemented).

This section should have given you an idea of how working with Autofac lets you focus on writing your application – not extending or fussing over the intricacies of a DI container.

I hope this article has illustrated the kinds of rewards that will come from learning how to use Autofac. The next steps might be to:

Thanks to Rinat Abdullin, Luke Marshall, Tim Mead, and Mark Monsour for reviewing this article and providing many helpful suggestions. Without your help, I fear it would have been completely unintelligible. If it is still unintelligible, then all of the blame lies with me. :)

- 18th April, 2008: Initial post

- 9th September, 2010: Article updated