Contents

Introduction

When I was developing a relational database engine, I was testing some queries in Microsoft SQL Server, and I found that some simple queries were taking a very long time to be executed, or I received a message "not enough space on the disk". After some investigation, I found that the problem was in the saving of the query result, or to be more accurate, the time to save the recordset cursor values. So, I tried to overcome this time issue in my design. This article will take a simple overview about recordset cursors, SQL statement execution, and then take a look at a simple query and explain the problem that slows down the performance of most DBMSs. Then, I'll introduce the idea of virtual cursors, and apply the idea to more sophisticated queries.

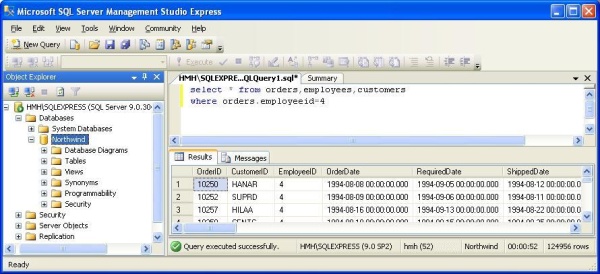

The SQL statement "Select * from orders,employees,customers where orders.employeeid=4" in SQL server takes 55 seconds to execute. I know that SQL Server can search in the field orders.employeeid for the value 4 in no more than 0 ms, but the problem is taking the result and combining it with that from two other tables (employees, customers) and saving the output cursor. That means, if the output result contains a big or a huge number of rows, SQL Server takes a lot of time to save the whole result, which motivated me to think about finding a way to overcome this problem in my company's engine.

I know that this is not a normal query and the cross product of the three tables returns 664,830 rows, but if you look at my execution time for the same query, you can find the difference, and it will motivate you to read the whole article to know the idea behind the virtual cursor. The following figure displays my engine time to execute the same query. It takes less than 1 millisecond.

Actually, SQL server takes no time to execute the query; the total time depends on the final resultant cursor vector; if it is too large, it takes a long time, or returns an error of "not enough space on the disk". If it is small, it takes no time to store it. And as a proof for its speed, if we use the query "Select count(*) from ...", it takes no time. So, the problem is in the saving of the cursor values. For example, for the query:

Select * from Orders, Employees, Customers, Products

WHERE Orders.EmployeeID IN (4, 5, 6)

AND Employees.EmployeeID IN (1, 2, 3)

AND Customers.CustomerID LIKE 'A%'

SQL Server takes 3 seconds to return 244,860 rows (it takes 16 ms to return the same rows in my engine). If you try to delete the condition "Customers.CustomerID LIKE 'A%'", you can go make a sandwich in the time you get a result; it takes about 35 seconds!!! While my engine takes 1 ms to get 5,448,135 rows. Any way, let us start an overview about the recordset cursor and it internal structure, and then discuss cursor expansion as an introduction to virtual cursors. Please take your time to read each section, as each section is the key for the next section.

Recordset Cursor

To interact with any database management system, you should execute a SQL statement with a Recordset object. the Recordset object executes the input query and stores the results in a certain data structure to enable the caller to enumerate through the execution result. The enumeration usually is done with the functions:

int GetRecordCount() | return the number of rows |

bool IsBOF() | check if the cursor is at the top of the rows |

bool IsEOF() | check if the cursor is at the end of the rows |

void MoveNext() | move to the next row |

void MovePrev() | move to the previous row |

void MoveFirst() | move to the first row |

void MoveLast() | move to the last row |

Move(int nRows) | move nRows from the current row |

MoveTo(int nRow) | move to nRow |

The following figure represents the location of the Cursor component in the DCMS components:

Let us have a simple example to try to find a suitable structure to represent the Cursor. I'll assume that I have four tables: T1, T2, T3, and T4. F1 is a foreign key in T1, and a primary key in T2.

For the query "Select * from T1,T2", we have the result of a cross join, as in the following table:

| T1.F1 | T2.F1 |

| B | A |

| C | A |

| A | A |

| A | A |

| C | A |

| B | B |

| C | B |

| A | B |

| A | B |

| C | B |

| B | C |

| C | C |

| A | C |

| A | C |

| C | C |

So, we can imagine the result as a view of rows, and the cursor is just a vector of values ranging from 0 to the number of rows-1. The cursor functions are just incremented and decremented: a variable between the min and max values. But, what is the case if we have a condition that limits the result, for example, if we modify the input query to: "Select * from T1,T2 where T2.F1=T1.F1"? In this case, we have the result as:

So, the result is a subset of the cross join of the two tables (the product of the two tables). As in the following figure:

So, the cursor vector just included the items (2, 3, 5, 11, 14), and the rows count is just the length of the vector (5 rows). A simple algorithm to map the cursor values to the fields record values, in its simple form, is:

void CRecordSet::GetFieldValue(CField* pField, VARIANT& var)

{

int nFieldRecord = GetFieldRecord(pField);

pField->GetRecord(nFieldRecord, var);

}

int CRecordSet::GetFieldRecord(CField* pField, bool bUseCursor)

{

int nCursor = bUseCursor ? m_vCursor[m_nCursor] : m_nCursor;

int nTableCount = m_vTables.size(), nTableSize, nPrefixSize = 1;

for (int n = 0; n < nTableCount; n++)

{

nTableSize = m_vTables[n]->GetRecordCount();

if(m_vTables[n] == pField->m_pTable)

return (nCursor / nPrefixSize) % nTableSize;

nPrefixSize *= nTableSize;

}

return -1;

}

GetFieldRecord is a simplified version of my original code. It maps the recordset internal cursor (m_nCursor) through the cursor vector m_vCursor which includes the final result as in figure 1. To understand the function, we should first understand the cross product of any number of tables as it is the secret behind this function. The cross product for two tables is just repeating each row from the second table with all the rows of the first table. That is clear in the left side table of figure 1. So, if we execute:

Select * from T3, T4

we get the rows:

| T3.F2 | T4.F3 |

| 1 | X |

| 2 | X |

| 3 | X |

| 4 | X |

| 1 | Y |

| 2 | Y |

| 3 | Y |

| 4 | Y |

| 1 | Z |

| 2 | Z |

| 3 | Z |

| 4 | Z |

Each item of T4 is repeated with the whole rows of T3, which is the key here. In the algorithm, you can find a variable nPrefixSize which is initialized to "1". So, if we iterate through the recordset tables (m_vTables) while multiplying nPrefixSize with each table size, for the first table, nPrefixSize equal to 1. Each row is repeated once. Then, nPrefixSize is multiplied with the first table size. So, for the second table, nPrefixSize equal to the first table size. Each row for it repeats with the size of the first table times. This iteration continues till we reach the table of the field:

if(m_vTables[n] == pField->m_pTable)

return (nCursor / nPrefixSize) % nTableSize;

Divide nCursor by nPrefixSize to remove the repetition, then take the reminder of dividing the result by nTableSize. This algorithm can be applied for any number of tables. So, we can map the cursor position to a field row value with a simple and short for loop.

Recordset Execution

Before digging into my target of recordset cursor construction, let us have a look at the general SELECT statement structure.

SELECT ..... | Specifies what fields or aggregate/mathematical functions to display | Necessary |

DISTINCT | Specifies what all returned rows must be unique | Optional |

FROM table0, table1, ..., tablen | Specifies the tables to initialize the recordset view | Necessary |

WHERE ...... | Specifies the conditions to filter the recordset view | Optional |

GROUP BY field0, field1, ..., fieldn | Groups data with the same value for field0, field1, ..., fieldn | Optional |

HAVING ...... | Specifies conditions to filter the recordset view after GROUP BY | Optional |

ORDER BY field0, field1, ..., fieldn | Sort the data based on the value in field0, field1, ..., fieldn | Optional |

The Select section can contain field names or math operations on the fields, or aggregate functions (count, sum, avg, min, max, stdev).

The following activity diagram shows the steps of execution of a SELECT statement. I'll talk here only about the part ExecuteWhere.

The ExecuteWhere uses the "WHERE ......." conditions to filter the cross join of the "FROM tablename(s)" part. The function does Boolean operations between sub-conditions; each condition is a filter of one or more fields of the specified table(s). For example, in the following condition:

(orders.orderdate>'5/10/1996' and employees.employeeID=3) and shipname like 'Toms*'

the ParseCondition operation constructs an execution stack like this:

and | and | orders.orderdate > '5/10/1996' | employees.employeeID = 3 | shipname like 'Toms*' |

|

|

I'll describe three ways to execute the previous query. The first one is for clarifying the idea of direct filtering, the second is the key for the virtual cursor (so, take time to understand it), but it takes a lot of memory in some cases, and the third is the virtual cursor solution which has the power of the second solution plus less memory usage.

Direct View Filtering

The first step is to assume that the recordset is fully expanded by the cross join of the two tables (Orders, Employees). So, the total number of records is equal to the size of Orders multiplied by the size of Employees. The second step is to loop through this record count and call the function GetFieldRecord(pField, false) for the field that needs to be filtered, and add to the cursor vector only the values that match the condition (e.g.: orders.orderdate>'5/10/1996'). So, after the loop, we have a cursor that can share in boolean operations with other cursors to have the final cursor of the recordset.

So, the function calls a function search for the top of the stack, which calls its two operands and asks them for search, then takes their two cursors and do a boolean operation depending on its operator (AND, OR, XOR). I think you understand that that is a recursion operation, no need to waste time and space here to discuss it.

Advantages

- This can be used for a "Having" execution (no indexes for aggregate functions output)

- It can be used to filter fields of mathematical expressions like: sin(t1.f1)/cos(t2.f2/t3.f3)^2

Disadvantages

- Large number of comparisons as we compare the expanded recordset view (cross join)

- Comparisons are done with field values, which is very slow (field indices should be used)

- Each condition cursor can take a lot of memory in some cases

Cursor Expansion

First, we need to understand the concept of expanding the cursor. So, I need to take a very simple example, then enlarge the scale with a sophisticated one. If we have a table like "Orders" in the NorthWind database, and want to execute a query like:

Select * from Orders

we get 830 rows (the cursor vector is equal to the table length). But, if we execute a query like:

Select * from orders where freight<0.2

then, we get 5 rows with a cursor vector of (48, 261, 396, 724, 787). These values are a direct mapping to the full table rows, and we can get the table row number as I described in the section "Recordset Cursor". But, what is the case if we have two or three tables in the query, and we have a filter like where freight<0.2. Should we use the first way: "Direct view filtering", to filter the whole view of the three tables? Imagine the three tables: Orders, Employees, and Customers. The cross join (full view) of the tables will have 664830 rows. We don't have this view expanded in the memory, we just have the cursor vector that includes a serial from 0 to 664829, and then using the algorithm of the "Recordset Cursor", we can reach the right record number of any field. But in the case of the filter (where freight<0.2), how can we construct the cursor vector without "Direct View Filtering"? That is the question!!!

How can we transfer the vector of the query "Select * from orders where freight<0.2" (48, 261, 396, 724, 787) to the vector of the query "Select * from orders,employees,customers where freight<0.2" (48, 261, 396, 724, 787, 878, 1091, 1226, ......, 664724, 664787) which includes 4005 rows? I think you know now what the meaning of Cursor Expansion is, so we can define it as: "Cursor Expansion is the process of expanding a cursor of one (or more) table(s) (resulting from a search with table indexes) to a cursor over the cross join of this (these) table(s) with many tables".

That expansion depends on many factors:

- Location of the table in the cross join (table of the filter):

For three tables, we have three positions for the Orders table: 0, 1, and 2. It depends on its order in the input query. So, we must have an algorithm that considers the whole case.

- Number of tables that share in the filter:

For example, if we have a condition like "Employees.employeeid=Orders.employeeid" (relation condition), we have two tables. The expansion depends on the location of the two tables and the distance between them, if they are sequenced or separated by other tables.

Example of Cursor Expansion

Suppose we have our tables:

and we have the query "SELECT T1.F1,T2.F1,T3.F2 FROM T1,T2,T3 WHERE T1.F1='C'".

- First, using the indexes of T1.F1, we get the records (1,4)

- Second, we need to cross join this result with T2, T3 to get the result:

The final result is a subset of the cross join of the three tables T1, T2, and T3, with cursor values (1, 4, 6, 9, 11, 14, 16, 19, 21, 24, 26, 29, 31, 34, 36, 39, 41, 44, 46, 49, 51, 54, 56, 59).

And, if we change the order of the three tables in the query like this: "SELECT T1.F1,T2.F1,T3.F2 FROM T2, T1, T3 WHERE T1.F1='C'", it will be (3, 4, 5, 12, 13, 14, 18, 19, 20, 27, 28, 29, 33, 34, 35, 42, 43, 44, 48, 49, 50, 57, 58, 59), and for the order of "SELECT T1.F1,T2.F1,T3.F2 FROM T2, T1, T3 WHERE T1.F1='C'", it will be (12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59).

So, the order of tables affects the output cursor values (we get the same data, just the order is different; to get a certain order, we can use Order By). So, we need an algorithm to expand the condition vector to the final cursor depending on the order of the shared tables. One can say, "Instead of that, we can construct a vector for each field containing its records, and use them to retrieve values with the cursor position". But, that will take a lot of space to keep these vectors for all the selected fields, especially if the number of fields is large (over ~ 20 fields). In addition to the wasted space, we need a very sophisticated algorithm to do boolean operations between conditions (T1.F1='C' AND T3.F2=2). But, in our case of saving only cursor values (relative to the cross join of the sharing tables), for each condition, we can do boolean operations simply between conditions' cursor values, using a simple algorithm like set_intersection and merge of the STL library.

In the whole case, the view (output) size is equal to the condition cursor size multiplied by the other tables' sizes.

view size = condition size * other tables' sizes

Back to the section Recordset Cursor and figures 2, 3. The recordset object contains a stack of conditions saved in a tree structure as in figure 3. Each node represents an object of type WhereItem. The execution of the query starts at the top WhereItem of the stack, which receives a reference to the recordset cursor. The Recordset Cursor is a simple vector of values and a group of functions, like that:

class CCursor : public vector<__int64>

{

public:

... constructors

public:

vector<CTable*> m_vTables;

public:

CCursor& operator=(const CCursor& input);

CCursor& operator|=(const CCursor& input);

CCursor& operator&=(const CCursor& input);

CCursor& operator^=(const CCursor& input);

CCursor operator|(const CCursor& input);

CCursor operator&(const CCursor& input);

CCursor operator^(const CCursor& input);

__int64 GetRecordCount(bool bCursor = true);

int GetRecord(__int64 nRow, CIRField* pField, bool bOrdered = true);

bool Filter(CCursor& vCursor);

void Expand(CCursor& vCursor);

... order by, group by, and distinct functions

};

Each WhereItem may be an operator (node with two operands), or an operand (leaf - direct condition). So, if the top of the stack is a leaf, it will directly apply the condition to the WhereItem tables (assigned in the parsing process - out of this article's scope). If it is an operator, it will call its two operands' Search function and apply its operator to the output cursors. So, we can imagine a code like that:

void WhereItem::Search(CCursor& cursor)

{

if(m_cOperator) {

CCursor copy = m_vCursor;

m_pOperands[0]->Search(m_vCursor);

m_pOperands[1]->Search(copy);

switch(m_cOperator)

{

case 'a': m_vCursor &= copy; break; case 'o': m_vCursor |= copy; break; case 'x': m_vCursor ^= copy; break; }

}

else {

if(m_vFields.size() == 1)

m_vFields[0]->Search();

else if(!m_bRelation) m_vCursor.Filter(m_vFields[0], m_vFields[1], m_strQuery, m_op);

}

cursor.Filter(m_vCursor);

}

Top of the stack takes the recordset cursor which contains all the FROM tables, but the leaf nodes may contain one or more tables. And, each node contains the tables of its operands (ordered as Recordset FROM tables). So, imagine the input query and its node working tables:

SELECT * FROM

Categories,Products,Employees,Customers,Orders

WHERE

Categories.CategoryID = Products.CategoryID AND

Customers.CustomerID = Orders.CustomerID AND

Employees.EmployeeID = Orders.EmployeeID

As you can see from the WhereItem::Search function, it calls cursor.Filter(m_vCursor) to expand the parent cursor (input to the function from the parent). For example, the lower AND of figure 4 calls its operands with the cursor that contains the tables Employees, Customers, and Orders. Operand 0 has a cursor of the tables Customers, Orders. So, it takes the cursor (relation cursor) on tables Customers, Orders, and tries to expand it to the tables Employees, Customers, Orders. And, operand 1 has a cursor of the tables Employees, Orders. So, it takes the cursor (relation cursor) on the tables Employees, Orders, and tries to expand it to the tables Employees, Customers, Orders. After that, the two operands' cursors are expanded with the same tables (with the same order). So, we can apply the boolean operations safely.

switch(m_cOperator)

{

case 'a': m_vCursor &= copy; break; case 'o': m_vCursor |= copy; break; case 'x': m_vCursor ^= copy; break; }

The process is done till we expand the cursor of the top stack WhereItem with the recordset cursor, which may include more tables, as each node collects tables from its children. The key here is that each leaf/node is expanded to its parent node tables only, not the recordset tables. So, it accelerates the entire execution. As I mentioned before, the cursor expansion for any condition depends on the condition tables order relative to its parent tables. If there is no condition, the tables are cross joined, but with the condition, we have the cross join of the condition cursor with the other tables. After some examples, I found that I needed to calculate some variables that are shared in the expansion process:

__int64 m_nViewSize;

__int64 m_nPrefixSize;

__int64 m_nGroupSize;

__int64 m_nMiddleSize;

__int64 m_nRecordCount;

As in the following figure:

m_nViewSize = T1.size * T3.size * T5.size * condition.size;

m_nPrefixSize = T1.size;

m_nGroupSize = T2.size;

m_nMiddleSize = T3.size;

m_nRecordCount = T1.size * T2.size * T3.size * T4.size * T5.size;

The function Filter(CCursor& vCursor) of the cursor takes the cursor of the condition (filter) and expands it to its tables (or from another side, filters the cross join of its tables by the condition cursor).

bool CCursor::Filter(CCursor& vCursor)

{

if(vCursor.m_vTables.size() == m_vTables.size())

{ *this = vCursor;

return true;

}

m_nViewSize = vCursor.size(), m_nMiddleSize = 1, m_nPrefixSize = 1;

if(m_nViewSize == 0)

return true;

vector<int> vTableOrder;

for (vector<CTable*>::iterator table = vCursor.m_vTables.begin();

table != vCursor.m_vTables.end(); table++)

vTableOrder.push_back(m_vTables.lfindIndex(*table));

int nTableCount = m_vTables.size(), nTableSize;

for (int nTable = 0; nTable < nTableCount; nTable++)

if(vTableOrder.lfindIndex(nTable) == -1)

{

m_nViewSize *=

(nTableSize = m_vTables[nTable]->GetRecordCount());

for(vector<int>::iterator i =

vTableOrder.begin(); i < vTableOrder.end()-1; i++)

if(nTable > *i && nTable < *(i+1))

m_nMiddleSize *= nTableSize;

}

m_nGroupSize = 1;

bool bFound = false;

for (int nTable = 0; nTable < nTableCount; nTable++)

{

nTableSize = m_vTables[nTable]->GetRecordCount();

if(vTableOrder.lfind(nTable))

{ m_nGroupSize *= nTableSize;

bFound = true;

}

else

{

if(bFound)

break;

m_nPrefixSize *= nTableSize;

}

}

m_nSegmentSize = vCursor.size()*m_nMiddleSize*m_nPrefixSize;

Expand(vCursor);

return true;

}

The previous function initializes the variables needed for cursor expansion. It is time now to introduce the Expand function. Remember, the Expand function works as in the definition "Cursor Expansion is the process of expanding a cursor of one (or more) table(s) (resulting from a search with table indexes) to a cursor over the cross join of this (these) table(s) with many tables".

To find the way to expand a condition filter to the cross join values, I did an example by hand, and investigated the results to find the general expression to calculate the values. The following tables show the trial for the query:

Select * from T1,T2,T3,T4,T5 where T3.F2=T5.F2

Imagine first the result of the query: "Select * from T3,T5 where T3.F2=T5.F2"; then we can expand its cursor to the tables T1, T2, T3, T4, T5.

and for the expanded query "Select * from T1,T2,T3,T4,T5 where T3.F2=T5.F2":

Actually, that was not the only trial. I tried many samples, but each trial needed a very large Excel sheet to illustrate the expansion, which is difficult to be included in the article. Finally, I found the following general expression: NC=m*G*P+(C+m)*P+p: where NC is the new cursor value and C is the old one. I implemented the following Expand function to map the old cursor to the new sharing tables:

void CCursor::Expand(CCursor& vCursor)

{

resizeEx((int)m_nViewSize);

__int64 nForeignMatch, nViewIncrement = 0,

nSegmentSize = vCursor.size()*m_nMiddleSize*m_nPrefixSize, nCursor;

__int64 nMiddle, nMatch;

vector<__int64>::iterator _first = vCursor.begin(),

_end = vCursor.end(), _dest = begin();

while(m_nViewSize)

{

__int64 nMaxForeignMatch = m_nGroupSize;

for(vector<__int64>::iterator i = _first;

i != _end; i += nForeignMatch,

nViewIncrement += m_nMiddleSize,

nMaxForeignMatch += m_nGroupSize)

{

for(nForeignMatch = 0; i+nForeignMatch != _end &&

(*(i+nForeignMatch)) < nMaxForeignMatch;

nForeignMatch++);

for(nMiddle = 0; nMiddle < m_nMiddleSize; nMiddle++)

{

nCursor = (nMiddle + nViewIncrement) *

m_nGroupSize * m_nPrefixSize;

for(nMatch = 0; nMatch < nForeignMatch; nMatch++)

for (__int64 nPrefix = 0, c = nCursor +

(*(i+nMatch)%m_nGroupSize)*m_nPrefixSize;

nPrefix < m_nPrefixSize; nPrefix++)

*(_dest++) = c+nPrefix;

}

}

m_nViewSize -= nSegmentSize;

}

}

The algorithm starts by resizing the cursor with the expected view size. To understand the meaning of Segment Size, we should first understand how we can estimate the output view size. Actually, the view size should be the product of the condition size with the remaining tables' sizes (check figure 5). And, it can be calculated by using another method. It can be:

m_nViewSize = vCursor.size()*m_nMiddleSize*

m_nPrefixSize*(product of tables after last condition table)

// in our case: no tables after last condition table T5, So

m_nViewSize = 5 * 3 * 15 = 225

nSegmentSize is simply equal to vCursor.size()*m_nMiddleSize*m_nPrefixSize. Any way, I hope you understand the idea of Cursor Expansion, no need to fully understand the algorithm now, as I think that any one who knows the idea can extract the algorithm and implement it in his own way.

Advantages

- Simple and fast algorithm.

- Simple boolean algorithms between expanded cursors using STL merge and intersect algorithms.

Disadvantages

- The main problem of Cursor Expansion is the heavy memory usage as the expanded cursor may use a lot of memory; even if we use the hard disk to keep it, it will take a long time to be saved and retrieved to do boolean operations. The following section discusses this disadvantage.

Let us check the query and have some measurements from the Windows Task Manger:

Select *

from orders,employees,customers,orderdetails,shippers,suppliers

where

customers.customerid=orders.customerid and

employees.employeeid=orders.employeeid and

orders.orderid=orderdetails.orderid and

orders.shipvia=shippers.shipperid

The following table includes each condition and its cursor size before and after expansion:

| No. | Condition | Expansion tables | Before expansion | After expansion | Size |

| 1 | customers.customerid = orders.customerid | orders, employees, customers, orderdetails, shippers | 825 rows | 48,002,625 rows | 366 MB |

| 2 | employees.employeeid = orders.employeeid | orders, employees, orderdetails, shippers | 830 rows | 5,365,950 rows | 41 MB |

| 3 | orders.orderid = orderdetails.orderid | orders, orderdetails, shippers | 2155 rows | 6,465 rows | 50.50 KB |

| 4 | orders.shipvia = shippers.shipperid | orders, orderdetails, shippers | 830 rows | 1,788,650 rows | 13.6 MB |

| 5 | condition3 and condition4 | orders, orderdetails, shippers | 2155 rows | 19,395 rows | 151.5 KB |

| 6 | condition2 and condition5 | orders, employees, orderdetails, shippers | 2155 rows | 191,795 rows | 1.46 MB |

| 7 | condition1 and condition6 | orders, employees, customers, orderdetails, shippers | 2155 rows | 62,176 rows | 485.7 KB |

If you notice, the condition customers.customerid=orders.customerid takes 366 MB after its cursor expansion (!!!), while it was 6600 bytes before expansion (825 rows * sizeof(__int64)). The following figures show the Windows Task Manger during the query execution:

To overcome this problem, I thought about a Virtual Cursor which I will demonstrate in the next section.

SQL Server again: I don't think that SQL Server works the same way. Actually, it doesn't take memory during query execution or for the final result. But, if the final cursor is too large, it takes a long time as it saves it to the hard disk, which may fail if there is not enough space on the hard disk, or if it needs more area to be saved. Anyway, there is a problem in the way that SQL Server saves the final cursor if it is huge. So, read the next section to check if it can help solve this problem.

Virtual Cursor

In the previous section, we introduced the idea of Cursor Expansion and how this expansion is useful to do boolean operations between expanded cursors of query conditions. But, we faced the problem of heavy memory usage and the risk of out of memory. So, I'll introduce a new idea for Cursor Expansion.

What if we don't expand cursors at all and leave them unexpanded. You may ask "but we need to expand them for the cross join of shared tables". You are right, but, as you know, we have the algorithm of Cursor Expansion at the Expand() function, so we can keep the same algorithm and expand the cursor values on demand. Yes, that is the idea. We can make a new function GetCursor() that receives the required row number and use the same algorithm to calculate the cursor value (relative to the cross join). So, we only need to keep the variables that share the algorithm to use it in the function. You may say "it will be slow". You are right too. But, if we add some caching and extend the cache window to an optimum number, we can accelerate the process. In addition, I have added some tricks to optimize the speed and jump faster to the required cursor value.

So, the solution now can be summarized in keeping the cursor without expansion and expanding only a small window (e.g.: 10240) of cursor values, and sliding this window as needed foreword or backward depending on the cursor type. So, we replace the size of the expanded cursor with only its original size plus the size of the cache window.

GetCursor Algorithm

The GetCursor algorithm is the same as the Expand GetCursor, except that it expand only a small window of cursor values. So, we can take the same algorithm with some modifications. To simplify the code, we do these modifications step by step. The initial code is as follows:

__int64 CCursor::GetCursor(__int64 nRow)

{

if(empty() || m_bSerial)

return nRow;

if(m_bVirtual == false)

return (*this)[(int)nRow];

if(m_nCacheRow != -1 && nRow >= m_nCacheRow &&

nRow < m_nCacheRow+m_nCacheIndex)

return m_vCache[nRow-m_nCacheRow];

m_vCache.resizeEx(m_nCachePageSize);

m_nCacheRow = nRow;

m_nCacheIndex = 0;

__int64 nSegment = nRow/m_nSegmentSize, nMiddle,

nMatch, nPrefix, nForeignMatch;

__int64 nViewIncrement = nSegment*m_nPageViewIncrement,

nAdded = nSegment*m_nSegmentSize,

nViewSize = m_nViewSize-nAdded;

while(nViewSize > 0)

{

__int64 nForeignMatchIndex = 0;

for(iterator i = begin(), _end = end();

i != _end; i += nForeignMatch,

nViewIncrement += m_nMiddleSize)

if(nForeignMatch = m_vForeignMatch[nForeignMatchIndex++])

for(nMiddle = 0; nMiddle < m_nMiddleSize; nMiddle++)

for(nMatch = 0; nMatch < nForeignMatch; nMatch++)

for(nPrefix = 0; nPrefix < m_nPrefixSize; nPrefix++)

if(nAdded++ >= nRow)

{

m_vCache[m_nCacheIndex++] =

(nMiddle + nViewIncrement) *

m_nGroupSize * m_nPrefixSize +

(*(i+nMatch)%m_nGroupSize)*m_nPrefixSize +

nPrefix;

if(m_nCacheIndex == m_nCachePageSize)

return m_vCache[0];

}

nViewSize -= m_nSegmentSize;

}

return m_vCache[0];

}

m_nCachePageSize is the cache window size with a default value of 10240.m_nCacheIndex is the actual cache window size.m_nCacheRow is the start row of the cache window.m_vCache is the cache window vector.

To accelerate the execution of the functions, we can add some checks to the for loops. Look for the nested loops:

for(nMiddle = 0; nMiddle < m_nMiddleSize; nMiddle++)

for(nMatch = 0; nMatch < nForeignMatch; nMatch++)

for(nPrefix = 0; nPrefix < m_nPrefixSize; nPrefix++)

if(nAdded++ >= nRow)

they can be:

if(m_nCacheIndex == 0 && nRow-nAdded > m_nMiddleSize*nForeignMatch*m_nPrefixSize)

nAdded += m_nMiddleSize*nForeignMatch*m_nPrefixSize;

else

for(nMiddle = 0; nMiddle < m_nMiddleSize; nMiddle++)

if(m_nCacheIndex == 0 && nRow-nAdded > nForeignMatch*m_nPrefixSize)

nAdded += nForeignMatch*m_nPrefixSize;

else

for(nMatch = 0; nMatch < nForeignMatch; nMatch++)

if(m_nCacheIndex == 0 && nRow-nAdded > m_nPrefixSize)

nAdded += m_nPrefixSize;

else

for(nPrefix = 0; nPrefix < m_nPrefixSize; nPrefix++)

if(nAdded++ >= nRow)

Each if statement is to avoid doing the loop if there is no need to do it. Anyway, it is not correct to try to explain the function here, as it needs a white board and a marker to breakdown each detail and get an example for each part. I am interested only in the idea and the problem it faces, not its details.

Boolean operations with Virtual Cursor: Boolean operations are done between cursors of conditions. What is the case if cursors are not expanded? How can we intersect or merge them? I mentioned before that I am using the simple algorithm set_intersection and merge of the STL library. These algorithms take the two cursors (vectors) and do its work and output the result to a destination vector. But, in the case of the Virtual Cursor, we don't have a vector. We only have a cache window of the vector. Let us first have a look at the STL set_intersection algorithm and see how we can use it to do our task.

STL set_intersection

template<class _InIt1,

class _InIt2,

class _OutIt> inline _OutIt set_intersection(_InIt1 _First1, _InIt1 _Last1,

_InIt2 _First2, _InIt2 _Last2, _OutIt _Dest)

{ for (; _First1 != _Last1 && _First2 != _Last2; )

if (*_First1 < *_First2)

++_First1;

else if (*_First2 < *_First1)

++_First2;

else

*_Dest++ = *_First1++, ++_First2;

return _Dest;

}

The algorithm iterates through the two vectors linearly, and if two values are equal, it adds it to the destination. I'll use the same idea, but instead of getting the value from the vector, I'll call GetCursor(). And, because of caching and the foreword cursor (default implementation), it will be very fast. Here is a part of the &= operator of the CCursor class:

CCursor& CCursor::operator&=(const CCursor& input)

{

if(input.empty())

clear();

else if(m_bVirtual || input.m_bVirtual)

{

vector<__int64> dest;

dest.set_grow_increment(10240);

__int64 nCursor[2] = { GetCursor(0),

((CCursor*)&input)->GetCursor(0) };

__int64 nSize0 = GetCursorCount(),

nSize1 = ((CCursor*)&input)->GetCursorCount();

for (__int64 n0 = 0, n1 = 0; n0 < nSize0 && n1 < nSize1; )

if (nCursor[0] < nCursor[1])

nCursor[0] = GetCursor(++n0);

else if (nCursor[0] > nCursor[1])

nCursor[1] = ((CCursor*)&input)->GetCursor(++n1);

else

dest.push_backEx(nCursor[0]),

nCursor[0] = GetCursor(++n0),

nCursor[1] = ((CCursor*)&input)->GetCursor(++n1);

assignEx(dest);

m_bVirtual = false;

}

else

resizeEx(set_intersection(begin(), end(), (iterator)input.begin(),

(iterator)input.end(), begin())-begin());

...

return *this;

}

In the same way, we can implement the other operators (|= , ^=, -=). The output cursor is not virtual, so the variable m_bVirtual is set to false. The output cursor is not virtual, but it can be taken by its composer WhereItem and made virtual relative to the parent of WhereItem. To clarify the previous statement, we should know that the cursor is made virtual if its condition contains tables less than its parent tables. So, we have to expand it or make it virtual. One can ask, what about Order By, Group By, and Distinct? How can we order a virtual cursor? Is that possible? Actually, I tried to do that and thought about it many times, but I failed to find a clear idea about ordering a virtual cursor. But, the good point here is Order By is done over the final cursor of the recordset, which is usually small as it is the result of some filtering conditions. So, to solve this problem, if the query contains Order By, Group By, or Distinct, I expand the final cursor as explained in the section Cursor Expansion.

bool CRecordset::ExecuteWhere()

{

m_vCursor.m_vTables = m_vFromTables;

if(m_strWhere.IsEmpty() == false)

{

m_vWhereStack[0]->Search(m_vCursor, false);

if(m_vGroupByFields.empty() == false || m_bDistinct ||

m_vOrderFields.empty() == false)

m_vCursor.Expand();

}

else

m_vCursor.m_bSerial = true;

return true;

}

Note the condition:

if(m_vGroupByFields.empty() == false || m_bDistinct ||

m_vOrderFields.empty() == false)

m_vCursor.Expand();

and look at figure 2 to see that this function is called before the Order By or Group By execution.

After applying the technique of virtual cursor with the query:

Select *

from orders,employees,customers,orderdetails,shippers,suppliers

where

customers.customerid=orders.customerid and

employees.employeeid=orders.employeeid and

orders.orderid=orderdetails.orderid and

orders.shipvia=shippers.shipperid

we can check each condition and its cursor size in the following table:

| No. | Condition | Expansion tables | Cursor | Size |

| 1 | customers.customerid = orders.customerid | orders, employees, customers, orderdetails, shippers | 825 rows | 6600 Bytes |

| 2 | employees.employeeid = orders.employeeid | orders, employees, orderdetails, shippers | 830 rows | 6640 Bytes |

| 3 | orders.orderid = orderdetails.orderid | orders, orderdetails, shippers | 2155 rows | 17 KB |

| 4 | orders.shipvia = shippers.shipperid | orders, orderdetails, shippers | 830 rows | 6640 Bytes |

| 5 | condition3 and condition4 | orders, orderdetails, shippers | 2155 rows | 17 KB |

| 6 | condition2 and condition5 | orders, employees, orderdetails, shippers | 2155 rows | 17 KB |

| 7 | condition1 and condition6 | orders, employees, customers, orderdetails, shippers | 2155 rows | 17 KB |

Note that the maximum cursor size is just 17 KB, while it was 366 MB in the Expansion case.

Thanks to...

Thanks to God and thanks to the Harf Company which gave me the chance to develop this interesting project.

Updates

- 01-05-2008: Initial post.