Abstract

Java 5 (JDK 1.5) introduced the concept of Generics or parameterized types. In this article, I introduce the concepts of Generics and show you examples of how to use it. In Part II, we will look at how Generics are actually implemented in Java and some issues with the use of Generics.

Issue of Type-Safety

Java is a strongly typed language. When programming with Java, at compile time, you expect to know if you pass a wrong type of parameter to a method. For instance, if you define:

Dog aDog = aBookReference;

where, aBookReference is a reference of type Book, which is not related to Dog, you would get a compilation error.

Unfortunately though, when Java was introduced, this was not carried through fully into the Collections library. So, for instance, you can write:

Vector vec = new Vector();

vec.add("hello");

vec.add(new Dog());

…

There is no control on what type of object you place into the Vector. Consider the following example:

package com.agiledeveloper;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.Iterator;

public class Test

{

public static void main(String[] args)

{

ArrayList list = new ArrayList();

populateNumbers(list);

int total = 0;

Iterator iter = list.iterator();

while(iter.hasNext())

{

total += ((Integer) (iter.next())).intValue();

}

System.out.println(total);

}

private static void populateNumbers(ArrayList list)

{

list.add(new Integer(1));

list.add(new Integer(2));

}

}

In the above program, I create an ArrayList, populate it with some Integer values, and then total the values by extracting the Integers out of the ArrayList.

The output from the above program is a value of 3, as you would expect.

Now, what if I change the populateNumbers() method as follows:

private static void populateNumbers(ArrayList list)

{

list.add(new Integer(1));

list.add(new Integer(2));

list.add("hello");

}

I will not get any compilation errors. However, the program will not execute correctly. We will get the following runtime error:

Exception in thread "main" java.lang.ClassCastException:

java.lang.String at com.agiledeveloper.Test.main(Test.java:17)…

We did not quite have this type-safety with collections pre-Java-5.

What are Generics?

Back in the good old days when I used to program in C++, I enjoyed using a cool feature in C++ – templates. Templates give you type-safety while allowing you to write code that is general, that is, it is not specific to any particular type. While C++ templates is a very powerful concept, there are a few disadvantages with it. First, not all compilers support it well. Second, it is fairly complex that it takes quite an effort to get good at using it. Lastly, there are a number of idiosyncrasies in how you can use it that it starts hurting the head when you get fancy with it (this can be said generally about C++, but that is another story). When Java came out, most features in C++ that were complex, like templates and operator overloading, were avoided.

In Java 5, finally, it was decided to introduce Generics. Though Generics – the ability to write general or generic code which is independent of a particular type – is similar to templates in C++ in concept, there are a number of differences. For one, unlike C++ where different classes are generated for each parameterized type, in Java, there is only one class for each generic type, irrespective of how many different types you instantiated it with. There are, of course, certain problems as well in Java Generics, but that we will talk about in Part II. In this part I, we will focus on the good things.

The work of Generics in Java originated from a project called GJ1 (Generic Java) which started out as a language extension. This idea then went through the Java Community Process (JCP) as a Java Specification Request (JSR) 142.

Generic Type-Safety

Let’s start with a non-generic example we looked at to see how we can benefit from Generics. Let’s convert the code above to use Generics. The modified code is shown below:

package com.agiledeveloper;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.Iterator;

public class Test

{

public static void main(String[] args)

{

ArrayList<Integer> list = new ArrayList<Integer>();

populateNumbers(list);

int total = 0;

for(Integer val : list)

{

total = total + val;

}

System.out.println(total);

}

private static void populateNumbers(ArrayList<Integer> list)

{

list.add(new Integer(1));

list.add(new Integer(2));

list.add("hello");

}

}

I am using ArrayList<Integer> instead of the ArrayList. Now, if I compile the code, I get a compilation error:

Test.java:26: cannot find symbol

symbol : method add(java.lang.String)

location: class java.util.ArrayList<java.lang.Integer>

list.add("hello");

^

1 error

The parameterized type of ArrayList provides the type-safety. “Making Java easier to type and easier to type,” was the slogan of the Generics contributors in Java.

Naming Conventions

In order to avoid confusion between the generic parameters and the real types in your code, you must follow a good naming convention. If you are following good Java conventions and software development practices, you would probably not be naming your classes with single letters. You would also be using mixed case with class names, starting with upper case. Here are some conventions to use for Generics:

- Use the letter E for collection elements, like in the definition:

public class PriorityQueue<E> {…}

Use letters T, U, S, etc. for general types.

Writing Generic Classes

The syntax for writing a generic class is pretty simple. Here is an example of a generic class:

package com.agiledeveloper;

public class Pair<E>

{

private E obj1;

private E obj2;

public Pair(E element1, E element2)

{

obj1 = element1;

obj2 = element2;

}

public E getFirstObject() { return obj1; }

public E getSecondObject() { return obj2; }

}

This class represents a pair of values of some generic type E. Let’s look at some examples of usage of this class:

Pair<Double> aPair = new Pair<Double>(new Double(1), new Double(2.2));

If we try to create an object with types that mismatch, we will get a compilation error. For instance, consider the following example:

Pair<Double> anotherPair = new Pair<Double>(new Integer(1), new Double(2.2));

Here, I am trying to send an instance of Integer and an instance of Double to an instance of Pair. However, this will result in a compilation error.

Generics and Substitutability

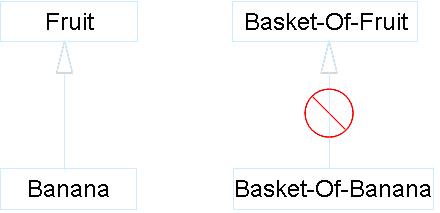

Generics honors the Liskov’s Substitutability Principle4. Let me explain that with an example. Say, I have a Basket of Fruits. To it I can add Oranges, Bananas, Grapes, etc. Now, let’s create a Basket of Banana. To this, I should only be able to add Bananas. It should disallow adding other types of fruits. Banana is a Fruit, i.e., Banana inherits from Fruit. Should Basket of Banana inherit from Basket for Fruits, as shown in the figure below?

If Basket of Banana were to inherit from Basket of Fruit, then you may get a reference of type Basket of Fruit to refer to an instance of Basket of Banana. Then, using this reference, you may add a Banana to the basket, but you may also add an Orange. While adding a Banana to a Basket of Banana is OK, adding an Orange is not. At best, this will result in a runtime exception. However, the code that uses Basket of Fruits may not know how to handle this. The Basket of Banana is not substitutable where a Basket of Fruits is used.

Generics honors this principle. Let’s look at this example:

Pair<Object> objectPair = new Pair<Integer>(new Integer(1), new Integer(2));

This code will produce a compile time error:

Error: line (9) incompatible types found :

com.agiledeveloper.Pair<java.lang.Integer> required:

com.agiledeveloper.Pair<java.lang.Object>

Now, what if you want to treat different type of Pairs commonly as one type? We will look at this later in the Wildcard section.

Before we leave this topic, let’s look at one weird behavior though. While:

Pair<Object> objectPair = new Pair<Integer>(new Integer(1), new Integer(2));

is not allowed, the following is allowed, however:

Pair objectPair = new Pair<Integer>(new Integer(1), new Integer(2));

The Pair without any parameterized type is the non-generic form of the Pair class. Each generic class also has a non-generic form so it can be accessed from a non-generic code. This allows for backward compatibility with existing code or code that has not been ported to use Generics. While this compatibility has a certain advantage, this feature can lead to some confusion and also type-safety issues.

Generic Methods

In addition to classes, methods may also be parameterized.

Consider the following example:

public static <T> void filter(Collection<T> in, Collection<T> out)

{

boolean flag = true;

for(T obj : in)

{

if(flag)

{

out.add(obj);

}

flag = !flag;

}

}

The filter() method copies alternate elements from the in collection to the out collection. The <T> in front of the void indicates that the method is a generic method with <T> being the parameterized type. Let’s look at a usage of this generic method:

ArrayList<Integer> lst1 = new ArrayList<Integer>();

lst1.add(1);

lst1.add(2);

lst1.add(3);

ArrayList<Integer> lst2 = new ArrayList<Integer>();

filter(lst1, lst2);

System.out.println(lst2.size());

We populate an ArrayList lst1 with three values and then filter (copy) its contents into another ArrayList lst2. The size of lst2 after the call to the filter() method is 2.

Now, let’s look at a slightly different call:

ArrayList<Double> dblLst = new ArrayList<Double>();

filter(lst1, dblLst);

Here I get a compilation error:

Error:

line (34) <T>filter(java.util.Collection<T>,java.util.Collection<T>)

in com.agiledeveloper.Test cannot be applied to

(java.util.ArrayList<java.lang.Integer>,

java.util.ArrayList<java.lang.Double>)

The error says that it can’t send an ArrayList of different types to this method. This is good. However, let’s try the following:

ArrayList<Integer> lst3 = new ArrayList<Integer>();

ArrayList lst = new ArrayList();

lst.add("hello");

filter(lst, lst3);

System.out.println(lst3.size());

Like it or not, this code compiles with no error, and the call to lst3.size() returns a 1. First, why did this compile and what’s going on here? The compiler bends over its back to accommodate calls to generic methods, if possible. In this case, by treating lst3 as a simple ArrayList, without any parameterized type that is (refer to the last paragraph in the “Generics and Substitutability” section above), it is able to call the filter method.

Now, this can lead to some problems. Let’s add another statement to the example above. As I start typing, the IDE (I am using IntelliJ IDEA) is helping me with code prompt as shown below:

It says that the call to the get() method takes an index and returns an Integer. Here is the completed code:

ArrayList<Integer> lst3 = new ArrayList<Integer>();

ArrayList lst = new ArrayList();

lst.add("hello");

filter(lst, lst3);

System.out.println(lst3.size());

System.out.println(lst3.get(0));

So, what do you think should happen when you run this code? May be runtime exception? Well, surprise! We get the following output for this code segment:

1

hello

Why is that? The answer is in what actually gets compiled (we will discuss more about this in Part II of this article). The short answer for now is, even though code completion suggested that an Integer is being returned, in reality, the return type is Object. So, the string "hello" managed to get through without any error.

Now, what happens if we add the following code:

for(Integer val: lst3)

{

System.out.println(val);

}

Here, clearly, I am asking for an Integer from the collection. This code will raise a ClassCastException. While Generics is supposed to make our code type-safe, this example shows how we can easily, with intent or by mistake, bypass that, and at best, end up with runtime exception, or at worst, have the code silently misbehave. Enough of those issues for now. We will look at some of these gotchas further in Part II. Let’s progress further on what works well for now, in this Part I.

Upper Bounds

Let’s say we want to write a simple generic method to determine the maximum of two parameters. The method prototype would look like this:

public static <T> T max(T obj1, T obj2)

I would use it as shown below:

System.out.println(max(new Integer(1), new Integer(2)));

Now, the question is how do I complete the implementation of the max() method? Let’s take a stab at this:

public static <T> T max(T obj1, T obj2)

{

if (obj1 > obj2)

{

return obj1;

}

return obj2;

}

This will not work. The > operator is not defined on references. Hmm, how can I then compare the two objects? The Comparable interface comes to mind. So, why not use the comparable interface to get our work done:

public static <T> T max(T obj1, T obj2)

{

Comparable c1 = (Comparable) obj1;

Comparable c2 = (Comparable) obj2;

if (c1.compareTo(c2) > 0)

{

return obj1;

}

return obj2;

}

While this code may work, there are two problems. First, it is ugly. Second, we have to consider the case where the cast to Comparable fails. Since we are so heavily dependent on the type implementing this interface, why not ask the compiler to enforce this? That is exactly what upper bounds does for us. Here is the code:

public static <T extends Comparable> T max(T obj1, T obj2)

{

if (obj1.compareTo(obj2) > 0)

{

return obj1;

}

return obj2;

}

The compiler will check to make sure that the parameterized type given when calling this method implements the Comparable interface. If you try to call max() with instances of some type that does not implement the Comparable interface, you will get a stern compilation error.

Wildcard

We are progressing well so far, and you are probably eager to dive into a few more interesting concepts with Generics. Let’s consider this example:

public abstract class Animal

{

public void playWith(Collection<Animal> playGroup)

{

}

}

public class Dog extends Animal

{

public void playWith(Collection<Animal> playGroup)

{

}

}

The Animal class has a playWith() method that accepts a Collection of Animals. The Dog, which extends Animal, overrides this method. Let’s try to use the Dog class in an example:

Collection<Dog> dogs = new ArrayList<Dog>();

Dog aDog = new Dog();

aDog.playWith(dogs);

Here, I create an instance of Dog and send a Collection of Dogs to its playWith() method. We get a compilation error:

Error: line (29) cannot find symbol

method playWith(java.util.Collection<com.agiledeveloper.Dog>)

This is because a Collection of Dogs can’t be treated as a Collection of Animals which the playWith() method expects (see the section “Generics and Substitutability” above). However, it would make sense to be able to send a Collection of Dogs to this method, isn’t it? How can we do that? This is where the wildcard or unknown type comes in.

We modify both the playMethod() methods (in Animal and Dog) as follows:

public void playWith(Collection<?> playGroup)

The Collection is not of type Animal. Instead it is of unknown type (?). Unknown type is not Object, it is just unknown or unspecified.

Now, the code:

aDog.playWith(dogs);

compiles with no error.

There is a problem however. We can also write:

ArrayList<Integer> numbers = new ArrayList<Integer>();

aDog.playWith(numbers);

The change I made to allow a Collection of Dogs to be sent to the playWith() method now permits a Collection of Integers to be sent as well. If we allow that, that will become one weird dog. How can we say that the compiler should allow Collections of Animals or Collections of any type that extends Animal, but not any Collection of other types? This is made possible by the use of upper bounds as shown below:

public void playWith(Collection<? extends Animal> playGroup)

One restriction of using wildcards is that you are allowed to get elements from a Collection<?>, but you can’t add elements to such a collection – the compiler has no idea what type it is dealing with.

Lower Bounds

Let’s consider one final example. Assume we want to copy elements from one collection to another. Here is my first attempt for a code to do that:

public static <T> void copy(Collection<T> from, Collection<T> to) {…}

Let’s try using this method:

ArrayList<Dog> dogList1 = new ArrayList<Dog>();

ArrayList<Dog> dogList2 = new ArrayList<Dog>();

copy(dogList1, dogList2);

In this code, we are copying Dogs from one Dog ArrayList to another.

Since Dogs are Animals, a Dog may be in both a Dog’s ArrayList and an Animal’s ArrayList, isn’t it? So, here is the code to copy from a Dog’s ArrayList to an Animal’s ArrayList.

ArrayList<Animal> animalList = new ArrayList<Animal>();

copy(dogList1, animalList);

This code, however, fails compilation with error:

Error:

line (36) <T>copy(java.util.Collection<T>,java.util.Collection<T>)

in com.agiledeveloper.Test cannot be applied

to (java.util.ArrayList<com.agiledeveloper.Dog>,

java.util.ArrayList<com.agiledeveloper.Animal>)

How can we make this work? This is where the lower bounds come in. Our intent for the second argument of Copy is for it to be of either type T or any type that is a base type of T. Here is the code:

public static <T> void copy(Collection<T> from, Collection<? super T> to)

Here we are saying that the type accepted by the second collection is the same type as T is, or its super type.

Where are We?

I have shown, using examples, the power of the Generics in Java. There are issues with using Generics in Java, however. I will defer discussions on this to the Part II of this article. In Part II, we will discuss some restrictions of Generics, how Generics are implemented in Java, the effect of type erasure, changes to the Java class library to accommodate Generics, issues with converting a non-Generics code to Generics code, and finally, some of the pitfalls or drawbacks of Generics.

Conclusion

In this Part I we discussed about Generics in Java and how we can use it. Generics provide type-safety. Generics are implemented in such a way that it provides backward compatibility with non-generic code. These are simpler than templates in C++ and also there is no code bloat when you compile. In Part II we discuss the issues with using Generics.

References

- GJ - A Generic Java Language Extension

- JSR 14

- Java SE Downloads - Previous Release - J2SE 5.0

- Oo Design Principles