Table of Contents

Below are the topics grouped by relationship to each other:

The purpose of this article will be to show you how to call the functions of another program through your own. This tutorial will be broken down into a series of steps, with a general example, followed up with an application of this knowledge to an actual program.

This article mostly uses a debugger (OllyDbg available for free to download here) and the Winject DLL injector (available for free to download online and included in callbin.zip). A C++ compiler is needed if you would like to compile the code for the DLLs. Compiling the test application and trying to work on that would most likely yield different results due to compiler settings, so it’s best to just use the one included in callbin.zip.

There are many reasons to reverse engineer the calls to internal functions of processes. For example, if you’ve ever seen any sort of game add-ons or “mods”, they may use this technique of calling a process' (the game's) internal functions to display text on the screen. Perhaps, you want to extend the hotkey functionality to a program. Maybe you’re interested in calling the “win” function in a game? Regardless, this technique has many wide applications than is mentioned here. The only things recommended for this tutorial are a decent knowledge of the x86 Assembly knowledge, and some knowledge of the Win32 API.

Let's start off with a pre-written application, then attempt to reverse engineer it in order to see how this function is called. We'll make a simple application to do some arithmetic, and output the values through a function. Here is our test application:

#undef UNICODE

#include <windows.h>

#include <stdio.h>

void mySecretFunction(int* param1, const char* param2,

DWORD param3, BYTE param4)

{

printf("----------Function Entry----------\n");

*param1 += 2008;

printf("param1: %i\n", *param1);

printf("param2: %s\n", param2);

param3 *= *param1;

printf("param3 (param3 *= *param1): %i\n", param3);

param4 = 0x90;

printf("param4: %i\n", param4);

printf("----------Function Exit----------\n");

}

int main(void)

{

int anArgument = 123;

for(;;)

{

if(GetAsyncKeyState(VK_F11) & 1)

mySecretFunction(&anArgument,

"This is the original text!",

123456, 4);

else if(GetAsyncKeyState(VK_F1) & 1)

break;

}

return 0;

}

This is just a function that I quickly wrote that accepts four parameters (1 by reference, 3 by value). The big advantage of writing your own and reversing it is that you already know what to look for. When trying to call a function by the address of an application that you don't have the source code to, you should be prepared to do a lot of extra work, since it’s definitely nowhere near as easy. What we're going to do is reverse engineer the debug build of this program (included in callbin.zip) to see exactly what happens step by step. Why the debug build, and not a release build with optimizations off? My personal justification for this is that it may make the analysis a bit easier for the debugger, but for this, it's pretty irrelevant. I also forgot about that idea until I finished this article in its entirety (main reason). If you were to look at the release build of this program, depending on the compiler optimizations, the mySecretFunction(...) might become inlined with main, and it would look drastically different since the parameters might be stored in static locations. Plus, since the function might possibly be inlined, attempting to call it by address would be a pretty useless search. So, let’s get to analyzing, and open up OllyDbg.

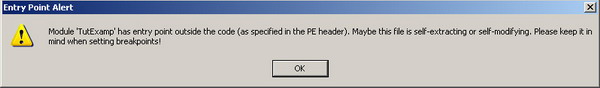

In the OllyDbg window, hit F3, and find TutExample.exe. After opening it up, you’ll see this message box pop up:

You can just hit the OK button and continue; this warning pops up due to the nature of the debug build (built under the VS2008 IDE, for reference). Right clicking the main window and selecting Search for -> All intermodular calls, we come up with this new window:

This window shows calls to all the functions that our executable makes. We see it call printf from MSVCR90D.dll, GetAsyncKeyState from USER32.dll, and so on. By using this, we can locate where our main() and mySecretFunction(…) are. First, let’s start with main() and see how mySecretFunction(…) gets called. Double click on one of the GetAsyncKeyState functions, and OllyDbg will take you to the address where they are called. By clicking on the top one, OllyDbg takes us to something that looks like this:

Since we have the source code, we can cheat a bit, and just set a breakpoint (highlight line and press F2) on the GetAsyncKeyState, since we know that it controls whether we call mySecretFunction(…) or not. Since we don’t want to necessarily step into the function and see how USER32.dll implements it, let’s breakpoint the first GetAsyncKeyState function and continue setting breakpoints on every line up to and including the second GetAsyncKeyState function. After you’re done, you should have something that looks like this:

So, let’s begin analyzing – hit F9 (Run program). OllyDbg should immediately hit the first breakpoint and highlight the line. Let’s hit F2 line by line, and see what it does without any interference from us. We see that the program comes to this line:

0041152A 74 1A JE SHORT TutExamp.00411546

and takes the jump. We should also note that the key code for VK_F11 is 0x7A, which we see is pushed on the stack right before the call to GetAsyncKeyState. Now, we can analyze what this function is doing, or better yet, what it’s not doing. Let’s see what these lines that were skipped do:

0041152C 6A 04 PUSH 4

0041152E 68 40E20100 PUSH 1E240

00411533 68 EC574100 PUSH TutExamp.004157EC

00411538 8D45 F8 LEA EAX,DWORD PTR SS:[EBP-8]

0041153B 50 PUSH EAX

0041153C E8 D8FAFFFF CALL TutExamp.00411019

00411541 83C4 10 ADD ESP,10

00411544 EB 19 JMP SHORT TutExamp.0041155F

We see that three values are pushed on the stack, then the address of one is loaded into the EAX register, which is then pushed on the stack. We then call some function, and fix the stack after it returns, and continue back into our loop. This sounds pretty familiar, and is in fact the disassembled form of:

mySecretFunction(&anArgument, "This is the original text!", 123456, 4);

The four parameters are pushed on the stack in reverse order since the stack functions as LIFO (last in first out), and then our function is called at 0x00411019. So, let’s highlight the call line, and hit Enter to take us to our function. We see it takes us to this line:

00411019 E9 A2030000 JMP TutExamp.004113C0

which is just another jump to 0x004113C0. It turns out that our function is not located at 0x00411019, but is actually located at 0x004113C0. We can just hit Enter again on this line, and go to the function at that address. Once we go to 0x004113C0, we begin to see some familiar things, such as our function entry and exit printf statements. 0x004113C0 is the address that we want to call in our program, to call this function with our custom arguments. Before we get into that though, we should at least analyze what’s going on in our function, and see how it looks disassembled. They will be especially easy to follow since they are separated with printf calls. Also, looking at the source code, you can match it right up to the disassembled code.

Note: Those knowledgeable in Assembly can skip this part since the functions and explanations are pretty simple.

Before even analyzing this, if we look at the beginning of the function, we see:

00413690 55 PUSH EBP

00413691 8BEC MOV EBP,ESP

00413693 81EC C0000000 SUB ESP,0C0

This is normally called a prologue, and sets up a stack frame for the passed arguments, local variables, saved registers, and so on. At the end of this function, you will see a bunch of popped registers:

0041376E 81C4 C0000000 ADD ESP,0C0

00413774 3BEC CMP EBP,ESP

00413776 E8 CAD9FFFF CALL TutExamp.00411145

0041377B 8BE5 MOV ESP,EBP

0041377D 5D POP EBP

which is called the epilogue, and restores the state of the stack so the program can continue normally once this function is finished. All of the parameters, in this case, will be accessed as something added to EBP (base pointer). Variables that are passed as parameters to a function are [EBP+0x04*n], where n can be 1, 2, 3, etc.. [EBP+0x04] is where the return address is on the stack, making [EBP+0x08] the first parameter, [EBP+0x0C] the second parameter, and so on, adding 0x04 each time to get the next parameter. Arguments are [EBP+0x04*n], local variables will be [EBP-0x04*n]. Anyway, getting back to analyzing the first part, which dereferences param1 and adds 2008 (0x7D8) to it. I’ve commented the important parts, and for the most part, it is pretty self-explanatory, given a mnemonic knowledge of Assembly language. I won’t go too much into analyzing these things in text, since the comments in the picture give a clear description of what is happening. Let’s start with param1, and work our way to param4. I’m going to explain what is happening through comments next to the important lines in the disassembly. If you want to follow along with breakpoints in the debugger, you can set a breakpoint on this line then, and start analyzing:

004113F5 8B45 08 MOV EAX,DWORD PTR SS:[EBP+8]

You may ask why we’re skipping the following lines:

004113EB 83C4 04 ADD ESP,4

004113EE 3BF4 CMP ESI,ESP

004113F0 E8 50FDFFFF CALL TutExamp.00411145

This is because these lines don’t serve any purpose on our analysis, these three lines are just there to clean up after the printf call. Starting off:

*param1 += 2008;

printf("param1: %i\n", *param1);

printf("param2: %s\n", param2);

Setting a breakpoint at 0x00411424:

param3 *= *param1;

printf("param3 (param3 *= *param1): %i\n", param3);

Setting a breakpoint at 0x0041143D:

param4 = 0x90;

printf("param4: %i\n", param4);

Setting a breakpoint at 0x00411464:

Anyway, now that we’ve analyzed everything and have a good solid understanding of how this thing looks and works, we can move on. We need to somehow call the function at a specific memory address in the process. We can't call it from our own process since each process is in its own virtual space. Let’s say that this code is compiled and the executable is run as secret.exe. Let's also say that we didn't know anything about virtual memory, and we were writing an application that had a function pointing to 0x004113C0, thinking that this is mySecretFunction(..). When we attempt to call that function, we would definitely not get the results that we want (due to the process being in a different address space). So, what we need to do is inject a DLL. By doing this, we can access the memory space of our secret.exe process. Let’s see what the code for this DLL would look like.

#include <windows.h>

DWORD WINAPI MyThread(LPVOID);

DWORD g_threadID;

HMODULE g_hModule;

void __stdcall CallFunction(int&, const char*, DWORD, BYTE);

INT APIENTRY DllMain(HMODULE hDLL, DWORD Reason, LPVOID Reserved)

{

switch(Reason)

{

case DLL_PROCESS_ATTACH:

g_hModule = hDLL;

DisableThreadLibraryCalls(hDLL);

CreateThread(NULL, NULL, &MyThread, NULL, NULL, &g_threadID);

break;

case DLL_THREAD_ATTACH:

case DLL_PROCESS_DETACH:

case DLL_THREAD_DETACH:

break;

}

return TRUE;

}

DWORD WINAPI MyThread(LPVOID)

{

int myInt = 1;

while(true)

{

if(GetAsyncKeyState(VK_F2) & 1)

{

CallFunction(myInt, "My custom text";, 1, 1);

}

else if(GetAsyncKeyState(VK_F3) &1)

break;

Sleep(100);

}

FreeLibraryAndExitThread(g_hModule, 0);

return 0;

}

void __stdcall CallFunction(int& param1, const char* param2, DWORD param3, BYTE param4)

{

typedef void (__stdcall *pFunctionAddress)(int&, const char*, DWORD, BYTE);

pFunctionAddress pMySecretFunction = (pFunctionAddress)(0x004113C0);

pMySecretFunction(param1, param2, param3, param4);

}

Starting off, it's pretty simple. We create a thread inside of the process that we injected this DLL into, and set up a loop waiting for our key press. Once we press F2, we should call our function, which in turns calls the internal function of the process. However, we get to pass our own parameters instead of the ones hardcoded into the original file. Our CallFunction(…) function has the same exact declaration as mySecretFunction(…), and in it, we set up a function pointer. We choose the __stdcall calling convention because it is the most common one that the C++ compiler uses. If need be, we could’ve further analyzed our disassembled executable, and seen how the stack is being cleaned up, in order to deduce whether another one such as __cdecl is being used instead. What we’re doing is creating a function pointer to address 0x004113C0 in the executable, which is the address that we found earlier to mySecretFunction(…). Once we find it, we call it with our custom parameters. So, let’s test this and see. Running the compiled code from the very beginning of this tutorial, we see this:

This looks normal, and is completely expected behavior from the program. Now, let’s inject our DLL, and see what happens when we press F2.

We can clearly see that something is different. But, is it what we expected? Let’s look at our parameters, and see what they should be according to the code of mySecretFunction(…). We passed 1, “My custom text”, 1, 1 to the function. 1 += 2008 = 2009 (correct). “My custom text” was outputted (correct). 1 *= 2009 = 2009 (correct). Param4 set equal to 0x90 (144 decimal, correct). It looks like everything worked perfectly. We can continue to press F11 to get the original function, or we can press F2 and get our custom one, but clearly, we see that something is different, and that we can choose to call this function with our own parameters.

An important thing to note is that it is very important to be careful with the data types. You should always step through each piece, and see what it is outputting. Later on, if we were to somehow mistake param2 for an int, instead of a const char*, we would be getting some unexpected results, or even have the program crash due to problems with memory. Viewing the address relative to EBP, we would see that param2 holds characters, while param1, param3, and param4 hold numbers of some type. Let’s examine some cases where we don’t necessarily declare the same parameter types as the original function, and see what happens. We should investigate a few variations, namely:

- Not using

const char* as param2. - Using different number based data types for

param1/3/4.

Let’s start with the first case. Going from top to bottom in the DLL code, here are the lines and what we change them to.

void __stdcall CallFunction(int&, int, DWORD, BYTE);

CallFunction(myInt, 12345, 1, 1);

void __stdcall CallFunction(int& param1, int param2, DWORD param3, BYTE param4)

typedef void (__stdcall *pFunctionAddress)(int&, int, DWORD, BYTE);

So, after making these changes, injecting our new DLL into the process, we can hit F11 and be greeted by a familiar message. However, when we hit F2, we see that the program crashes right at the point of outputting param2. There’s really not much to say about this except to be careful, and work with proper data types when it comes to two different things such as const char* and a numeric type. What happens if we change one of the other parameters then? Will the program still crash if we were to change the third parameter from DWORD to BYTE? The short answer is “no”; at least, this one won’t (you can try for yourself). We do, however, get some unexpected output from our parameters, which sort of makes calling the function useless if it doesn’t give us what we expect. The issue about our program not crashing is not universal either; it’s rather the exception than the rule. Programs may or may not crash depending on what is done with the parameters. Ours consists of just adding, multiplyin, and outputting; others may not be so friendly to taking BYTE types instead of DWORDs, or likewise.

Now, on to a practical example where we don’t know the source code and we need to do some guess work. As much as I don’t like giving simple programs such as Minesweeper or the standard Windows games as “real” examples, I can’t think of anything else of use that’s as common on desktops as these games, and where this technique can be used to achieve something truly useful. My real world example would be a large application or a game with lots of functionality where calling their functions can yield some really cool looking results. However, I would imagine that’s of too questionable legality, and also would violate some article submission guidelines of CodeProject. Anyway, let’s start our Minesweeper game, and see where we can apply this technique. Our window:

So, where would we apply this technique? Personally, I’m thinking that it’d be nice if we had a hotkey that would win the game for us. Let’s go to it then; but, before we start, we should lay out exactly what we’re going to do. Our objective is to:

- Find the function that Minesweeper uses that wins the game.

- See what parameters it takes, and how it works.

- Write a DLL that we can inject, and set a hotkey to call this function for us.

But, how do we find this mystery function? There are a number of ways to go from here, each with varying difficulty. My approach to this problem is to see how the game behaves when you win a game. I noticed that if I had sound enabled, the game would play a sound when I won a game (or the clock ticked, or I hit a bomb). We can use this information and track down the API that plays the sound, then working backwards, we can come upon the function that is executed when you win the game. So, open the game up in OllyDbg, and hit F9 (Run program). After doing this, you can hit Ctrl+A and let OllyDbg analyze the code some more. We’re looking for an API that plays sound; so, right click the main window, and go to Search for -> All Intermodular calls. You’ll be greeted with a pretty large list, larger than the one in the sample program. Click the “Destination” tab to sort these in alphabetical order by API name. There are tons of APIs, but something should catch our eye.

PlaySoundW sounds pretty interesting. According to MSDN, here is what the PlaySound API does:

The PlaySound function plays a sound specified by the given file name, resource, or system event. (A system event may be associated with a sound in the Registry or in the WIN.INI file.)

BOOL PlaySound(

LPCTSTR pszSound,

HMODULE hmod,

DWORD fdwSound

);

This is definitely what we want, so let’s set a breakpoint on all three of them. After doing this, we should go back to the main Minesweeper window, and click on a tile to start a game. Immediately after that, we should hit a breakpoint at:

01003937 |> FF15 68110001 CALL DWORD PTR DS:[<&WINMM.PlaySoundW>]

If we hit F9 to continue running this program, we will see that this specific one is called each time the timer increases by 1. If we take the breakpoint off and continue, we see that this API doesn’t get called anymore when the timer increases. However, it also does not get called when you win or lose a game. This means that this specific one is responsible for all three, and that working backwards, we can see what is calling it.

We see that we’ve got jumps to this function from 0x01003913 and 0x01003925. So, let’s set breakpoints on them, and see what is going on.

01003903 |. 68 05000400 PUSH 40005

01003908 |. FF35 305B0001 PUSH DWORD PTR DS:[1005B30]

0100390E |. 68 B2010000 PUSH 1B2

01003913 |. EB 22 JMP SHORT WINMINE.01003937

01003915 |> 68 05000400 PUSH 40005

0100391A |. FF35 305B0001 PUSH DWORD PTR DS:[1005B30]

01003920 68 B1010000 PUSH 1B1

01003925 |. EB 10 JMP SHORT WINMINE.01003937

We see these two segments are pushing three parameters on the stack, and then calling PlaySoundW. If we take note from earlier, the LPCTSTR pszSound parameter of the ticking noise is 0x1B0. Here, we have 0x1B2 and 0x1B1. Just by using logic, you can guess that these two correspond to the explosion sound and the victory sound. But, which one? That’s what we’re going to test. Let’s set a breakpoint on each one, and see. We notice that if we start a new game and happen to come upon a bomb, we get a breakpoint at:

0100390E |. 68 B2010000 PUSH 1B2

If we win a game, 0x1B1 is pushed. So, we have 0x1B2 as the explosion sound, 0x1B1 as the victory sound, and 0x1B0 as the ticking sound. Therefore, the critical piece of the code is this:

01003915 |> 68 05000400 PUSH 40005

0100391A |. FF35 305B0001 PUSH DWORD PTR DS:[1005B30]

01003920 68 B1010000 PUSH 1B1

01003925 |. EB 10 JMP SHORT WINMINE.01003937

Now, working backwards again, we want to find what calls this. If we click on 0x01003915, we see this in the main window:

Note: we can also right click the command and go to Find references to -> Selected command (Ctrl+R). Going backwards once again to 0x010038FE and investigating what is around there, we come upon this block of code, with 0x010038ED as the beginning of this whole function:

010038ED /$ 833D B8560001 >CMP DWORD PTR DS:[10056B8],3

010038F4 |. 75 47 JNZ SHORT WINMINE.0100393D

010038F6 |. 8B4424 04 MOV EAX,DWORD PTR SS:[ESP+4]

010038FA |. 48 DEC EAX

010038FB |. 74 2A JE SHORT WINMINE.01003927

010038FD |. 48 DEC EAX

010038FE |. 74 15 JE SHORT WINMINE.01003915

01003900 |. 48 DEC EAX

01003901 |. 75 3A JNZ SHORT WINMINE.0100393D

We see that the value in 10056B8 gets compared with 3, which we can deduce as three cases of a switch statement. The value of [ESP+4] is moved into EAX, and then we see what it is and takes a corresponding action. We’re not quite there yet, but it seems that we’re getting close. Let’s go to the top of the function and see what calls this. Select the line, and hit Ctrl+R to see what’s calling this.

Let’s set a breakpoint on all three, and start a new game. Immediately, we should hit this:

0100382B |. E8 BD000000 CALL WINMINE.010038ED

Since we haven’t even started playing yet, let alone won, we should just remove the breakpoint and move on. A second or two after we continue, we hit this line:

01003002 |. E8 E6080000 CALL WINMINE.010038ED

This isn’t what we want either. We’ve got it narrowed down to one now.

010034CF |. E8 19040000 CALL WINMINE.010038ED

If we experiment around a bit, we can see that 0x010034CF is called when we win or lose a game. Now, we just have to make the distinction and find out what determines whether we win or lose. Let’s take a look at this function as a whole:

0100347C /$ 8325 64510001 >AND DWORD PTR DS:[1005164],0

01003483 |. 56 PUSH ESI

01003484 |. 8B7424 08 MOV ESI,DWORD PTR SS:[ESP+8]

01003488 |. 33C0 XOR EAX,EAX

0100348A |. 85F6 TEST ESI,ESI

0100348C |. 0F95C0 SETNE AL

0100348F |. 40 INC EAX

01003490 |. 40 INC EAX

01003491 |. 50 PUSH EAX

01003492 |. A3 60510001 MOV DWORD PTR DS:[1005160],EAX

01003497 |. E8 77F4FFFF CALL WINMINE.01002913

0100349C |. 33C0 XOR EAX,EAX

0100349E |. 85F6 TEST ESI,ESI

010034A0 |. 0F95C0 SETNE AL

010034A3 |. 8D0485 0A00000>LEA EAX,DWORD PTR DS:[EAX*4+A]

010034AA |. 50 PUSH EAX

010034AB |. E8 D0FAFFFF CALL WINMINE.01002F80

010034B0 |. 85F6 TEST ESI,ESI

010034B2 |. 74 11 JE SHORT WINMINE.010034C5

010034B4 |. A1 94510001 MOV EAX,DWORD PTR DS:[1005194]

010034B9 |. 85C0 TEST EAX,EAX

010034BB |. 74 08 JE SHORT WINMINE.010034C5

010034BD |. F7D8 NEG EAX

010034BF |. 50 PUSH EAX

010034C0 |. E8 A5FFFFFF CALL WINMINE.0100346A

010034C5 |> 8BC6 MOV EAX,ESI

010034C7 |. F7D8 NEG EAX

010034C9 |. 1BC0 SBB EAX,EAX

010034CB |. 83C0 03 ADD EAX,3

010034CE |. 50 PUSH EAX

010034CF |. E8 19040000 CALL WINMINE.010038ED

010034D4 |. 85F6 TEST ESI,ESI

010034D6 |. C705 00500001 >MOV DWORD PTR DS:[1005000],10

010034E0 |. 5E POP ESI

010034E1 |. 74 2C JE SHORT WINMINE.0100350F

010034E3 |. 66:A1 A0560001 MOV AX,WORD PTR DS:[10056A0]

010034E9 |. 66:3D 0300 CMP AX,3

010034ED |. 74 20 JE SHORT WINMINE.0100350F

010034EF |. 8B0D 9C570001 MOV ECX,DWORD PTR DS:[100579C]

010034F5 |. 0FB7C0 MOVZX EAX,AX

010034F8 |. 8D0485 CC56000>LEA EAX,DWORD PTR DS:[EAX*4+10056CC]

010034FF |. 3B08 CMP ECX,DWORD PTR DS:[EAX]

01003501 |. 7D 0C JGE SHORT WINMINE.0100350F

01003503 |. 8908 MOV DWORD PTR DS:[EAX],ECX

01003505 |. E8 77E6FFFF CALL WINMINE.01001B81

0100350A |. E8 9BE6FFFF CALL WINMINE.01001BAA

0100350F \> C2 0400 RETN 4

Let’s set a breakpoint on each line from the beginning of the function, all the way up to the end of the return statement. Since this function is called when you win and when you lose, you can begin by checking what parts of it are skipped when these conditions happen. After setting a breakpoint on all of these lines and losing a game, we find that these lines are skipped.

010034B4 |. A1 94510001 MOV EAX,DWORD PTR DS:[1005194]

010034B9 |. 85C0 TEST EAX,EAX

010034BB |. 74 08 JE SHORT WINMINE.010034C5

010034BD |. F7D8 NEG EAX

010034BF |. 50 PUSH EAX

010034C0 |. E8 A5FFFFFF CALL WINMINE.0100346A

We also find that the last statement of the function to be executed when you lose is:

010034E1 |. 74 2C JE SHORT WINMINE.0100350F

Now, to see what happens when you win. We find that the function gets executed in its entirety.

Note: If you’re following along in a debugger and your game stops at this line:

010034ED |. 74 20 JE SHORT WINMINE.0100350F

that is because the lines that come after this are to check to see whether you are eligible for the high score table.

So, what is the difference that determines the jump? We come to these lines:

010034B0 |. 85F6 TEST ESI,ESI

010034B2 |. 74 11 JE SHORT WINMINE.010034C5

Here, we’re testing to see if ESI is 0, and if so, we take the jump that skips over the section dealing with a won game. In other words, if ESI is 0, then we have lost. To see what the value of ESI is when we win, we can simply check the value of it in OllyDbg at that line.

We see that the value for ESI when we win is 1. So, where is ESI set? If we examine the function, we can see that near the beginning, there is this line:

01003484 |. 8B7424 08 MOV ESI,DWORD PTR SS:[ESP+8]

The first parameter into this function is moved into ESI. Why ESP, and not EBP as in the original example? This is because this function does not set up a stack frame like the other one, so the parameters are accessed through ESP instead of EBP. We see that the highest value of ESP is +8, and that this function returns 4, so we can deduce that it only takes one parameter. We can even verify this by checking the references to 0x0100347C and seeing only one PUSH statement before the call. We’ve achieved two out of three of our original objectives, so now, all that’s left is to just write our DLL to make a hotkey that calls this function with 1 as a parameter. Since we’re moving this parameter into a 32-bit register, we can have it as a type DWORD in our DLL (despite the DWORD PTR in the disassembly). In case anyone is interested in a description of the entire function, below are my notes from stepping through and quickly glancing over what happens.

Here, we can use the template of the DLL for the original function. There are just a few trivial things to change around. The new code is shown below:

#include <windows.h>

DWORD WINAPI MyThread(LPVOID);

DWORD g_threadID;

HMODULE g_hModule;

void __stdcall CallFunction(void);

INT APIENTRY DllMain(HMODULE hDLL, DWORD Reason, LPVOID Reserved)

{

switch(Reason)

{

case DLL_PROCESS_ATTACH:

g_hModule = hDLL;

DisableThreadLibraryCalls(hDLL);

CreateThread(NULL, NULL, &MyThread, NULL, NULL, &g_threadID);

break;

case DLL_THREAD_ATTACH:

case DLL_PROCESS_DETACH:

case DLL_THREAD_DETACH:

break;

}

return TRUE;

}

DWORD WINAPI MyThread(LPVOID)

{

while(true)

{

if(GetAsyncKeyState(VK_F3) & 1) {

CallFunction();

}

else if(GetAsyncKeyState(VK_F4) & 1)

break;

Sleep(100);

}

FreeLibraryAndExitThread(g_hModule, 0);

return 0;

}

void __stdcall CallFunction(void)

{

typedef void (__stdcall *pFunctionAddress)(DWORD);

pFunctionAddress pWinFunction = (pFunctionAddress)(0x0100347C); pWinFunction(1); }

Let’s test it out just for good measure. Start up a new instance of Minesweeper, and inject the DLL. Click on one of the tiles to start the game, then hit the F3 hotkey. The result? Hopefully, something similar to this.

You’ll notice that the full board doesn’t get revealed when you win, but that can be left as an exercise for the reader :-).

- 09.21.2008 - Article submitted.