Introduction

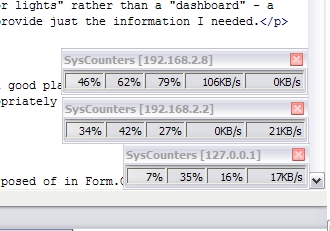

To make a long story short, I needed to monitor system performance counters not only on my workstation but also for several other computers on my home network, and without taking up the screen space of multiple System Monitor (Perfmon.exe) instances. I have some old computers doing file and print server and "development server" duties, and I wanted to keep an eye on the current CPU load, available memory, network activity, and so on. I only wanted "indicator lights" rather than a "dashboard" - a very condensed summary of the system's current status instead of fancy graphs and histograms. So, I wrote a C# application to provide just the information I needed.

Background

If you're not familiar with using performance counters, the System Monitor application (Perfmon.exe) and its Help file are a good place to start. I've read elsewhere that the actual performance counter names used as constructor parameters are localized, so this code will need to be changed appropriately and recompiled for non-English locales.

Using the code

Basically, some PerformanceCounter instances are programmatically created in the main form's Form.Load, and disposed of in Form.Closing. The whole form is little more than a StatusStrip component, with each of the PerformanceCounter values displayed in a ToolStripStatusLabel updated once every couple of seconds via a Timer.

The performance counters I chose to monitor were:

- total percent CPU processor time ("Processor", "% Processor Time")

- percent committed memory ("Memory", "% Committed Bytes In Use")

- percent page file usage ("Paging File", "% Usage")

- network adapter throughput

Monitoring CPU usage goes without saying, and based on my own observations, the amount of committed memory and page file usage together gave me a reasonable idea of how overburdened my computers are. Initially, I did use other indicators like available memory ("Memory", "Available MBytes") and commit limit ("Memory', "Commit Limit"), but to me, this was not as straightforward to read as the counters expressed in percents, where in general, the higher the values shown, the less responsive the computer will be. This was a personal choice, and obviously, other indicators will be more applicable in other situations.

private PerformanceCounter cpuCounter = null;

private PerformanceCounter ramCounter = null;

private PerformanceCounter pageCounter = null;

private PerformanceCounter[] nicCounters = null;

private void InitCounters()

{

try

{

cpuCounter = new PerformanceCounter

("Processor", "% Processor Time", "_Total", machineName);

ramCounter = new PerformanceCounter

("Memory", "Available MBytes", String.Empty, machineName);

pageCounter = new PerformanceCounter

("Paging File", "% Usage", "_Total", machineName);

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

SysCounters.Program.HandleException

(String.Format("Unable to access computer

'{0}'\r\nPlease check spelling and verify

this computer is connected to the network",

this.machineName));

Close();

}

}

private void tTimer_Tick(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

try

{

tsCPU.Text = String.Format("{0:##0} %", cpuCounter.NextValue());

tsRAM.Text = String.Format("{0} MB", ramCounter.NextValue());

tsPage.Text = String.Format("{0:##0} %", pageCounter.NextValue());

for (int i = 0; i < nicCounters.Length; i++)

{

ssStatusBar.Items[String.Format("tsNIC{0}", i)].Text =

String.Format("{0:####0 KB}",

nicCounters[i].NextValue() / 1024);

}

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

tTimer.Enabled = false;

SysCounters.Program.HandleException(ref ex);

Close();

}

}

private void DisposeCounters()

{

try

{

if (cpuCounter != null)

{ cpuCounter.Dispose(); }

if (ramCounter != null)

{ ramCounter.Dispose(); }

if (pageCounter != null)

{ pageCounter.Dispose(); }

if (nicCounters != null)

{

foreach (PerformanceCounter counter in nicCounters)

{ counter.Dispose(); }

}

}

finally

{ PerformanceCounter.CloseSharedResources(); }

}

Since a computer can have more than one network adapter, I decided to keep things simple and just monitor the throughput ("Bytes Total/sec") of each Network Interface present, excluding the "TCP Loopback Interface", of course. PerformanceCounterCategory.GetInstanceNames() returns a string array of the Network Interface instances, and I used that to create corresponding arrays of PerformanceCounters and ToolStripStatusLabels to display the current values.

Since I would need to programmatically create a variable number of counters for the Network Interfaces anyway, I decided it would be more consistent to create all the counters in code rather than use the PerformanceCounter components.

Command line

By default, the program will monitor performance counters on the local computer, unless the name or IP address of a remote computer is specified on the command line.

private void GetMachineName()

{

string[] cmdArgs = System.Environment.GetCommandLineArgs();

if ((cmdArgs != null) && (cmdArgs.Length > 1))

{ this.machineName = cmdArgs[1]; }

}

private bool VerifyRemoteMachineStatus(string machineName)

{

try

{

using (Ping ping = new Ping())

{

PingReply reply = ping.Send(machineName);

if (reply.Status == IPStatus.Success)

{ return true; }

}

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

}

return false;

}

Exception handling is kept fairly simple; catch the exception, show the user our error message, and then just call Form.Close().

Since I intend to run multiple instances of the SysCounters application (one for each computer I'm monitoring), I wanted to be able to save the screen position of each. After poking around in the System.Configuration namespace and spending too much time trying various things, I again went for the simplest option, using the AppSettings section of the application config file and creating a key-value pair for each instance. Since this uses a single application config file, it does open up some issues; the position saved by one user can be overwritten by a different user, and a non-administrator user may not be able to save settings at all.

private void LoadSettings()

{

int iLeft = 0;

int iTop = 0;

System.Configuration.Configuration config =

ConfigurationManager.OpenExeConfiguration(ConfigurationUserLevel.None);

try

{

int.TryParse(ConfigurationManager.AppSettings[String.Format

("{0}-Left", this.machineName)], out iLeft);

int.TryParse(ConfigurationManager.AppSettings[String.Format

("{0}-Top", this.machineName)], out iTop);

}

finally

{

this.Left = iLeft;

this.Top = iTop;

config = null;

}

}

private void SaveSettings()

{

System.Configuration.Configuration config =

ConfigurationManager.OpenExeConfiguration(ConfigurationUserLevel.None);

try

{

config.AppSettings.Settings.Remove

ring.Format("{0}-Left", this.machineName));

config.AppSettings.Settings.Remove

ring.Format("{0}-Top", this.machineName));

config.AppSettings.Settings.Add(String.Format("{0}-Left",

this.machineName), this.Left.ToString());

config.AppSettings.Settings.Add(String.Format("{0}-Top",

this.machineName), this.Top.ToString());

config.Save(ConfigurationSaveMode.Modified);

}

finally

{ config = null; }

}

Things to watch out for

Note that I've only tested this on Windows XP Pro SP 2 machines on a Workgroup home network, so I have not dealt with more complex permissions issues that may come up in other network environments.

In general, to monitor performance counters on a remote computer, you will need to first make sure of a couple of things on that particular machine. First, that you have a non-limited user account. Second, that "File and Printer Sharing for Microsoft Networks" is enabled in Network Connection properties. Third, that "Use simple file sharing" is disabled (in Explorer "Tools|Folder Options|View", make sure "Use simple file sharing" is unchecked in the listbox).

Conclusion

This application was meant as a simple, straightforward, "run and forget" utility without the need for additional configuration. There are additional tweaks and changes that could be made (saving settings per user profile, have it minimize to the Task Tray, convert it to an MDI app with each "monitor" instance as a child window), but it works fine for me as is.

Thanks for reading, and I hope this was of use to someone!