Introduction

With Python-Embedded XML, or in short PeXml, users can embed Python script in XML. The Python script will be evaluated at run time to generate data values. For example, PeXml can convert the following XML

<Data>

<StudentID>'SID0000' + str(dg.random.randrange(100)).zfill(3)</StudentID>

<Class>dg.round_robin(['Mon 7am', 'Tue 2pm', 'Thur 9am', 'Fri 1pm'])</Class>

<ExtraCredit>dg.extra_credit(0.2)</ExtraCredit>

</Data> into

<Data>

<StudentID>SID0000023</StudentID>

<Class>Tue 2pm</Class>

<ExtraCredit>No</ExtraCredit>

</Data> where the Python functions are implemented in a user-defined Python module.

#dg.py

import random

index = 0

def round_robin(l):

global index

index = index + 1

return l[index % len(l)]

def extra_credit(probability):

if random.random() < probability:

return 'Yes'

else:

return 'No' XML is widely used as input (or output) into web-service or other middle-tier transactions. When testing these transactions, a test engineer needs to pass in different values to validate different business logic. More often than not, the business logic can be highly complicated where random dummy data won't suffice. PeXml is designed to solve this issue by allowing test engineers to

- Implement complicates business logic to generate data values in the input XML,

- Flexibly change the business logic, and

- Preserve data dependency among parameters within one transaction or among transactions.

Background - Test Automation

Test automation is always high at concept but low at practice. Key challenges are:

- Complexity

- Flexibility

- Data Dependency

Complexity: A few lines of source code from a smart developer can implement very complicated business logic that require tens of even hundreds combinations of input parameters to exhaust. Traditionally a tester has to manually enumerate all combinations. It is a straightforward task but it requires far more amount of time than the often tight testing schedule would permit.

Test automation introduced another layer of complexity. Suppose we have documented all test cases. Manual execution of the test cases can tolerate defects in the test cases while automated execution cannot. A human tester can detect and fix errors when going through test cases, but a test program will simply crash. Thinking about testing the test program? The time it requires is explosive.

Load testing is a special type of automated test. Typically millions or even more transactions were executed during a load test. All of them have to be fully automated and it cannot tolerate any errors. If there is any error, the tester will scratch his head really hard to figure out whether it is an error of the test program, or the system cannot sustain the load. For example, a transaction emitted an error "data not found", a legitimate functional error at first glance. But the root cause could be that under heavy load a data loader failed to upload data into the database.

Flexibility: Suppose the tester had suffered endless sleepless nights and finally fixed all bugs in the test program. Usually at this time the testing cycle was closer to its end. He would hope to reuse the test program in next release so all the sleepless nights worth something. Tragedy is that business logic changed in the new release and he has to redo most of the things.

Changes of business logic are main drivers for new releases, especially for enterprise customers, who deem low priority for user interface look and feel and high priority for business process. In a fast pacing world where everyone wants to lower costs and improve productivity, tweaks of business process are more than usual. Just name a few examples: A supply chain manager wants to cut a few steps for a new product, a manufacturer wants to add a few tools on the production route, or an online retailer wants to gather new types of data of shoppers.

Specific to test automation, flexibility also means the capability to quickly switch between different scenarios. In load testing, normally a customer wants two scenarios: normal vs. stressed. Mix of load is also important. A database administrator may want to understand the system performance when most of transactions are read transactions vs. most are write transactions.

Data Dependency: There are two levels of data dependency. One is among parameters within one transaction, which we name Local Dependency. It is a normal practice that a certain combination of two or more data values triggers a particular business process. For example, a process control system may record oven temperatures at the beginning and the end of a baking process, and trigger an alarm if the difference is larger than a threshold. Test program has to have the capability to generate temperatures within the threshold for happy-path test cases and beyond the threshold for unhappy-path test cases.

The other is Global Dependency. Complex business processes can be built by gluing up multiple web services or other type of transactions. When validating such a business process, data integrity needs to be preserved among all transactions. For example, an online retailer may invoke multiple transactions for a customer. The customer's ID, a key parameter for all transactions, has to be persistent through all of them.

An elegant solution is to separate a piece of test program into two parts: one to model the process and the other to model the data. The benefit is that changes on the process model won't spill over to the data model, and vice versa. Flexibility is achieved by introducing configuration files for both the process model and the data model. A process model is usually no more than a sequence of transactions. With a configuration file, steps can be easily added, removed, or exchanged in a sequence to model changes of the business process or switch between test scenarios.

However a configuration file is naturally weak at expressing involved logic, especially when it comes to data dependency. For a data model, normally a configuration file can specify a constant value, a random number, a range of numbers, or a list of strings. Anything more than that require some sort of programming languages.

Scripting languages such as Python is a lightweight programming language that requires less programming skills and no compilation into binary code. Embedding scripting texts such as Python scripts into a configuration file will automatically solve the problem. Nowadays XML is the de facto standard for transactions' input and output. Thus we came up with the idea of Python-Embedded XML that can flexibly encode complicated data model and preserves local and global dependency.

Using the code

PeXml comes with two parts: a C++ DLL and a C# DLL. Correspondingly, the attached source code package contains two Visual Studio 2008 projects, a C++ project: PythonInterpreter for the C++ DLL and a C# project: PythonXML for the C# DLL.

The C++ DLL uses Boost.Python to invoke Python interpreter and evaluate Python script. The C# DLL uses XML DOM to traverse XML tree and calls the C++ DLL for Python evaluation. We choose this two-tier architecture because Boost.Python "enables seamless interoperability between C++ and the Python programming language"; and our test program is in C# so anyway we need to switch from C++ to C# at some point.

In principle, it is not a difficult task to implement everything in C++. It might be more preferable since both Python and Boost.Python are platform-independent. If everything is in C++, PeXml will also be platform-independent. Interested readers can carry it out as an exercise.

Prerequisites

Because PeXml uses both Python and Boost.Python, readers need to have both installed before using PeXml. For beginners, the best way is to download pre-built Windows installation packages. Multiple packages exist. What we use are ActivePython 2.7.2 and BoostPro 1.47.0.

Readers also need to make sure that both the Python DLL and Boost.Python DLLs are in the system path. Otherwise PeXml will complain that DLLs are not found.

python27.dll - Usually located at C:\Python27 or C:\Windows\system32

boost_python-vcnn-xx-yy-1_47.dll - Usually located at C:\Program Files\boost\boost_1_47\lib

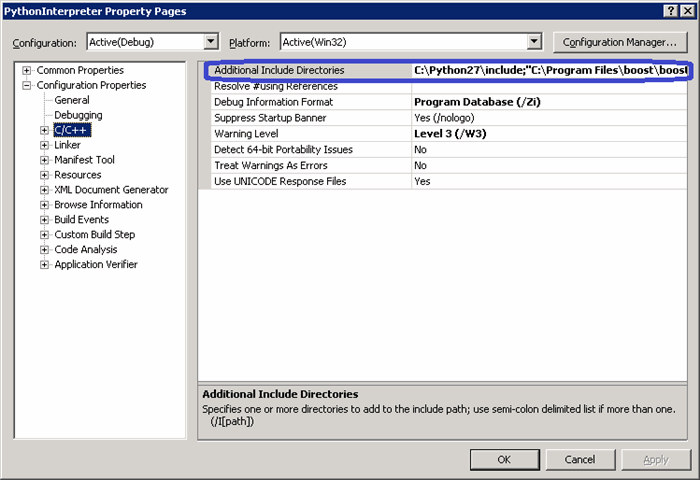

If readers want to compile the source code, in the C++ project: PythonInterpreter they need to set "Additional Include Directories" and "Additional Library Directories" to the right include and lib paths for Python and Boost.Python.

Build the PeXml solution will generate two DLLs, both are needed when using PeXml.

PythonInterpreter.dll

PythonXML.dll

A Working Example

To use PeXml, readers create a new C# project with Visual Studio 2008 and add reference to PythonXML.dll. Readers also need to copy both DLLs into the current path, otherwise it will complain that DLLs are not found.

We need to add the following namespaces:

using System.Xml;

using PythonXml;

And the following code snippet will load and evaluate a Python-Embedded XML.

static void Main(string[] args)

{

Interpreter interp = new Interpreter();

interp.InitPython(@"D:\\Python", "dg");

string xml = "<!-- Python-Embedded XML -->" +

"<Data><StudentID>'SID0000'+ str(dg.random.randrange(100)).zfill(3)</StudentID>" +

"<Class>dg.round_robin(['Mon 7am', 'Tue 2pm', 'Thur 9am', 'Fri 1pm'])</Class>" +

"<ExtraCredit>dg.extra_credit(0.2)</ExtraCredit></Data>";

XmlNode node = interp.Interp(xml);

System.Console.WriteLine(node.OuterXml);

}

First it initialize a new instance of class Interpreter, then it calls

InitPython(string path, string package)

to initialize a Python interpreter (or virtual machine) and import the user-defined Python module from path path with name package.py. The user-defined module defines functions that will be embedded in the XML. It can import other Python modules. Global variables can be defined to store values. At run time, different functions can refer to global variables to implement data dependency.

Then it calls

XmlNode Interp(string xml)

to evaluate a Python-Embedded XML and return an instance of XmlNode. The purpose to return a node object is that normally there will be some post work needed to perform on the node. Someone may want to check values of a couple of parameters; some may want to manipulate values of others. These type of tasks can be easily performed on a node object.

PeXml also provides a group of methods to set and get scalar values of global variables defined in the Python module.

public void SetString(string key, string value)

public void SetInt(string key, int value)

public void SetDouble(string key, double value)

public string GetString(string key)

public int GetInt(string key)

public double GetDouble(string key)

Using the dg.py at the beginning of this article as an example, the test program can set the value of the global variable index by

interp.SetInt("index", 5) Or it can get the current value of index by

int index = interp.GetInt("index") More On Python

The Python script embedded in the XML has to be an expression that evaluates to a string, or a function that returns a string. This removes the burden that PeXml handles different types of returned values. Since all data values in XML are strings, this restriction is appropriate.

For numerical values, Python has a built-in function str() to convert them to string. For example,

str(5)

str(6.0)

will convert the integer and float numbers to corresponding strings.

If users want to embed constant values into XML, they need to put it in Python string format, which is simply a string quoted by single or double quotation marks, and with special character escaped. For example,

'a Python string'

'C:\\Program Files\\boost\\boost_1_47' # a path where character \ is escaped

'It\'s a Python string' # character ' is escaped

Python interpreter will treat them as string expressions and return their corresponding values.

Global variables is defined at the top of the user-defined Python module. In a Python function, a global variable has to be indicated by the global statement. Otherwise Python will treat it as a local one.

For example, the following code snippet declares a global variable index, which is referenced in function round_robin().

index = 0

def round_robin(l):

global index

index = index + 1

return l[index % len(l)]

Each time the function

round_robin() is called, the global variable

index is increased by 1. Thus the next call will return the very next value in the list.

Global variables are used to implement local and global data dependency.

If round_robin() is called multiple time within a XML, it will return, in order, the values in the list. This can be used to generate mutually exclusive values.

For example, depending on the initial value of index, the following XML

<Data>

<Number>str(dg.round_robin([1, 2, 3, 4])</Number>

<Number>str(dg.round_robin([1, 2, 3, 4])</Number>

<Number>str(dg.round_robin([1, 2, 3, 4])</Number>

<Number>str(dg.round_robin([1, 2, 3, 4])</Number>

</Data>

will be translated to

<Data>

<Number>1</Number>

<Number>2</Number>

<Number>3</Number>

<Number>4</Number>

</Data>

No matter what's the initial value of index, one thing we can guarantee is that the Number parameters in the XML must have distinct values.

Boost.Python initialize a singleton virtual machine for a process. Thus Python global variable can also be used to implement global data dependency within a process. For example, suppose we have four transactions, Step1, Step2, Step3, and Step4. Their respective XMLs are

<Data>

<Number>str(dg.round_robin([1, 2, 3, 4])</Number>

</Data>

<Data>

<Number>str(dg.round_robin([1, 2, 3, 4])</Number>

</Data>

<Data>

<Number>str(dg.round_robin([1, 2, 3, 4])</Number>

</Data>

<Data>

<Number>str(dg.round_robin([1, 2, 3, 4])</Number>

</Data>

If the test program invokes the four transaction in a sequence, no matter what's the order of the sequence, we can guarantee that each step must have a distinct value for Number.

Points of Interest

Design Considerations

Why Python? We choose Python because of its outstanding interoperability with other programming languages. There is Boost.Python for seamless interoperability with C++ and there is also IronPython for interoperability with C#.

Why Boost.Python? For one, we prefer its seamless interoperability. For two, Boost.Python cleverly uses object to maintain reference count, and programmers won't need to worry about memory leak or garbage collection.

Why not make path and package name of the user-defined Python package as attributes in the XML Declaration? It is possible to put them as attributes in XML Declaration, such as

="1.0"="UTF-8"="D:\\Python"="dg"

But in this way logically the Python package is a property of a XML, conflicting against the concept of using global Python variables for global data dependency among multiple XMLs.

Known Issues

PeXml does not handles all Boost.Python exceptions. Unhandled Boost.Python exceptions will terminate the process. This is OK for us as we use PeXml mainly in test programs. The users are expected to have the know-how to deal with those exceptions. If this is intolerable for any users, proper exception handling can be implement following the example of PythonEval() in PythonInterpreter.cpp.

Length of string values returned from PythonInterpreter.dll is capped by 1K bytes. This is because we choose to use explicit marshalling between C++ and C# for strings. The C# side will initialize a StringBuilder with 1K bytes and pass it to C++ side to receive the returned string value. The advantage is safety. The disadvantage is flexibility. In our practices we didn't encounter any XML value longer than 1K bytes. Anyway, the limit can be enlarged effortlessly.

History

July 7th, 2012 - The first version.