| HTML5 for .NET Developers

By Jim Jackson II and Ian Gilman

In any HTML application with a significant amount of user interaction, you will encounter requirements that conflict with one another. This article based on chapter 8 of HTML5 for .NET Developers talks about merging the need for a responsive user interface with the requirement to perform complex, processor-intensive tasks.

You may also be interested in ...

|

Web workers are a very simple set of

interfaces that allow you to start work on a thread owned by the browser but

different from the thread used to update the interface. This means true

asynchronous programming for JavaScript developers. Current methods of yielding

a thread from one task to another is done automatically by the browser’s

JavaScript engine but the result, while often blazingly fast, is not truly

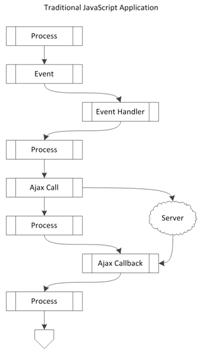

concurrent processing, where two things are working simultaneously. Figure 1

shows the traditional methodology.

Figure 1 Earlier versions of

HTML and JavaScript allowed only one thread to perform work for the

application. If a callback or an event was received, the current thread would

have to yield for that work to be processed.

This methodology was fine for simple applications and, as the

speed of JavaScript engines increased, it even works for many more complex

applications. A tremendous amount of research and development has been done to

get every last ounce of performance out of traditional JavaScript applications.

TIP Refer to Nicholas Zakas’ High Performance JavaScript by O’Reilly for insights into

how to get the most from a single thread in JavaScript.

The problem with the single thread, as you have probably

realized, is that if you are using canvas to build an image or calling a server

to round-trip a large data packet, there is really nothing you can do that will

not slow down your user interface, your complex task or both. As the client

side of web applications gets more complex, you will find that single thread is

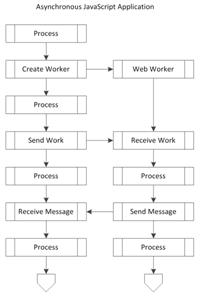

just not enough anymore. Figure 2 shows what the new world of web workers looks

like.

Figure 2 Using web workers, the

application can spawn a new thread and perform work there, communicating with

the primary thread as needed without affecting user interface performance.

A web worker’s lifetime can last only as long as your current

page exists in the browser. If you refresh the page or navigate to a different

page, that worker object will be lost and need to be restarted from scratch if

you want to have access to it again.

Rules for Web Workers

A web worker will execute inside its own thread in the browser.

It has access to server resources and any data passed to it from the host

thread. It also has the ability to start its own workers (called subworkers)

and will then become the host thread for those workers. A web worker can also

access the navigator

object which means it can communicate with the geolocation API. It can make its

own ajax calls and access the location object.

The web worker cannot access any part of the user interface. That

means that anything inside the window object is off-limits as is the document object.

In a JavaScript application, any variables declared are automatically in the

global scope, meaning they are attached to window. So your web worker will not be

able to access any application variables, functions or respond to any events or

callbacks from the rest of your application.

Tip: Because the worker object cannot access any user

interface elements, it is generally not advisable to pull in the jQuery

library. jQuery is designed to run on the UI thread so it will immediately

throw exceptions when loaded into a process that does not contain a window object.

A web worker uses a single JavaScript file to execute and, within

that script, can pull in other files when it starts up. This opens the

possibility for having your entire application logic reside on a thread

separate from the user interface thread but that is well outside the scope of

this chapter.

The specification states that web workers, by design, are not

intended for short-term execution and should not be counted upon to be

available after starting up. This means that the results of work you send to a

web worker should not have user interface dependencies. Web workers are useful

but heavy so try not to use a big hammer on a small nail.

Sending Work to Another Thread

A web worker is not a static object that is just available, like

geolocation. Rather, it is an object that you create and reference with a

variable. You do that by calling new on the Worker object and passing it a script file. The file

should be referenced by a complete URL or by a location relative to the current

page location in your web site.

var myWorker = new Worker('WorkerProceses.js');

Once created, the worker will not time out or stop its work

unless told to do so via the worker.terminate function. Because the JavaScript is

immediately executed into memory as soon as the script file is loaded, the

worker can begin performing work such as making calls to geolocation or making

ajax calls for data. It can also start sending messages back to its parent

thread immediately.

The host’s worker

object has a postMessage(string)

method it can use to pass regular strings or JSON data to the worker. The

worker also has a message

event that can be wired up using either the addEventListener function or by wiring a

function to the onmessage

event. Likewise, inside the worker script, you can call postMessage and attach to the message event. The

host process also has a worker.terminate

function that stops all work being performed by the worker object. Once terminate is

called, no additional messages will be sent or received by the worker object.

A Web Work Example

Create a new web application. Add an index.html page, a Scripts

folder and two JavaScript files inside it. Name one main.js and the other

myWorker.js. Inside the index page, add a script reference to the latest version

of jQuery at the top and a reference to scripts/main.js at the bottom before

the closing </body>

tag. Next, add an input button to test our functionality.

<input type=button id="testWorkers" value="Test Workers" />

Finally, inside main.js, add the following code to handle

document.ready and to create a simple object to contain our test code.

Listing 1 Creating a worker and sending messages to it

$(document).ready(function () {

workerTest.init(); #A

});

window.workerTest = {

myWorker: null,

init: function () {

self = this;

self.myWorker = new

Worker("/Scripts/myWorker.js"); #B

$("#testWorkers").live("click",

function () {

self.myWorker.postMessage("Test"); #C

}

);

self.myWorker.addEventListener("message",

function (event) {

alert(event.data); #D

},

false);

}

};

#A Initializes our object using the regular jQuery ready function.

#B Creates a new worker object and assign it as a local variable.

#C Sends the worker a message whenever the test button is clicked.

#D When the worker sends a message back to the host, notify the user.

In the worker object, we will show that the JavaScript begins

executing as soon as the script is loaded and that it can begin immediately

sending messages and responding to posts.

Listing 2 A simple web worker script example

count = 0; #A

init = function () {

self.count++; #B

self.postMessage("start count: " + count); #C

}

self.addEventListener("message", function (event) {

self.count++; #D

setTimeout(function () {

self.postMessage("Last Msg: " + event.data + #E

", count: " + count); #E

}, 1000);

}, false);

init(); #F

#A Since we do not have access to window, we cannot

assign variables to it by default. Variables here are scoped to the script

file.

#B Here, we update the count value to show that work

has been done.

#C Upon initialization, we can call the postMessage

event proving that messages can be sent not in response to any host request.

#D Update the count variable whenever a message is

received.

#E When a message is received, wait one second and respond with the message

sent and the current count value.

#F At the end of the script, we call the init function to start performing

work.

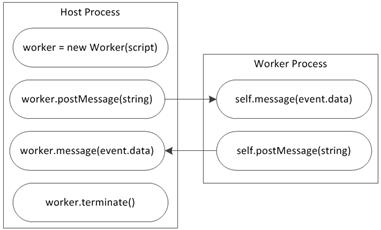

The overall interface between a host application and a web

worker is very simple, as you can see. The primary difference is that the host

calls functions on its worker variable, while the client calls the same

functions on self.

Figure 3 The host process can

post and receive messages using the same methods as the client except that the

host calls these methods on the worker object while the client process uses the

self keyword to execute these functions.

The MessageEvent Object

When receiving a message in either direction, the returned

object is a MessageEvent

object. It has a data

property that is a copy of the value posted, not a reference to the original

piece of data. In addition, it has a short list of properties that are used for

cross-document messaging. Cross-document messaging is a specification that

allows scripts from other domains to communicate.

Including Other Scripts

Bringing in other scripts is very easy inside a worker script.

You simply call the importScripts

function using the name of the script file or files to include. Keep in mind

that the script locations will be relative to the current worker script’s location

in the site. If you need to import multiple scripts, use a single importScripts

function call with comma separated script names.

importScripts("inclA.js", "inclB.js")

In this code, you could define variables varA and varB and they would immediately be available

inside the worker script since they will also be immediately executed. The

order of the scripts in the list will also be honored so dependencies can be

built up. If you need to load scripts conditionally you can also call importScripts

multiple times from anywhere in the code with different scripts or using

conditional logic to load different scripts. Finally, you can load the same

script multiple times but be careful since any variables initialized in the

external script and changed in your main worker process will be reset when the

script is reloaded, not to mention the fact that the script will be reloaded

from the server each time.

Ending the Worker Process

We mentioned that a web worker can be stopped by calling terminate. When

this happens, no further messages are received or sent from the worker process.

This is a true disposal of the worker process. Although calling postMessage

against the worker will not throw an exception, no work will be done. Also,

inside your worker process, any timers or other code that is executing will be

immediately stopped.

Web Worker Errors

When an exception is thrown from the web worker, it is handled

in the host using the error

event. The resulting event object has the following properties:

- message—Actual

error message encountered in the script.

- filename—File name

where the exception occurred.

- lineno—Line number

in the script file where the exception was encountered.

Summary

While the browser can certainly access the host system’s memory

and processor resources, doing any heavy processing will often cause the screen

to hang for a few moments. You may even encounter a browser message stating

that it thinks you have a runaway process. The Web Worker specification solves

this problem by allowing you to create a background worker that can do work on

a different thread, thus freeing up the user interface thread to perform screen

reflows and other more interactive logic.