In this chapter, we'll take a look at the various different types of shell commands that exist and how this can affect your work.

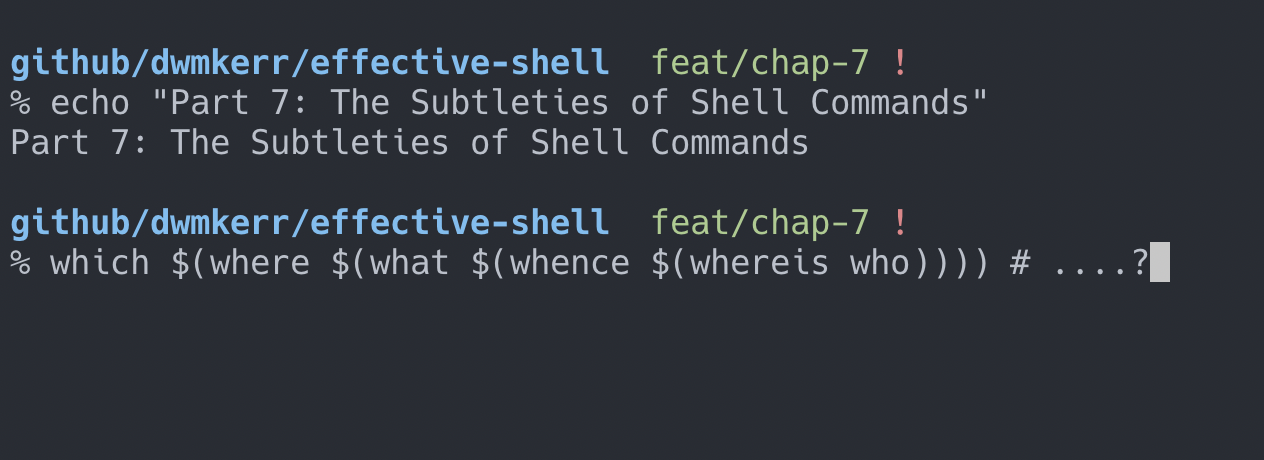

By the end of this chapter, you might even be able to make sense of the horrifying and perfectly syntactically valid code below:

which $(where $(what $(whence $(whereis who))))

What are Commands?

This is really important to understand! A command in a shell is something you execute. It might take parameters. Generally, it'll have a form like this:

command param1 param2

We've already seen many commands during this series:

ls # Show the contents of the current directory

cd ~ # Move to the user's home

cat file.txt # Output the contents of 'file.txt' to stdout

But to be an effective shell user, you must understand that not all commands are created equal. The differences between the types of commands will affect how you use them.

There are four types of commands in most shells:

- Executables

- "Built-Ins" (which we'll just call builtins from now on)

- Functions

- Aliases

Let's quickly dig in and see a bit more.

Executables - Programs

Executables are just files with the 'executable' bit set. If I execute the cat command, the shell will search for an executable named cat in my $PATH. If it finds it, it will run the program.

$ cat file.txt

This is a simple text file

What is $PATH? $PATH is the standard environment variable used to define where the shell should search for programs. If we temporarily empty this variable, the shell won't find the command:

$ PATH="" cat file.txt

bash: cat: No such file or directory

Normally your $PATH variable will include the standard locations for Linux programs - folders such as /bin, /sbin, /usr/bin and so on.

If you were to print the variable, you'd see a bunch of paths (they are separated by colons; I've put them on separate lines for readability):

/usr/local/bin

/usr/bin

/bin

/usr/sbin

/sbin

The shell will start with the earlier locations and move to the later ones. This allows local flavours of tools to be installed for users, which will take precedence over general versions of tools.

There will likely be other locations too - you might see Java folders, package manager folders and so on.

Executables - Scripts

Imagine we create a text file called dog in the local folder:

echo "🐶 woof 🐶"

If we make the file executable, by running chmod +x dog, then we can run this just like any other program - as long as we tell the shell to look for programs in the current directory:

$ PATH="." dog

🐶 woof 🐶

More common would be to run the program by giving a path:

$ ./dog

🐶 woof 🐶

Or just move it to a standard location that the shell already checks for programs:

$ mv dog /usr/local/bin

$ dog

🐶 woof 🐶

The point is that executables don't have to be compiled program code. If a file starts with #! (the 'shebang'), then the system will try to run the contents of the file with the program specified in the shebang.

We will look at shebangs in greater detail in a later chapter.

Builtins

OK, so we've seen executables. What about a command like this?

local V="hello" echo $V

You will not find the local executable anywhere on your system. It is a builtin - a special command built directly into the shell program.

Builtins are often highly specific to your shell. They might be used for programming (local for example is used to declare a locally scoped variable), or they might be for very shell-specific features.

This is where we need to take note. As soon as you are running a builtin, you are potentially using a feature that is specific to your shell, rather than a program that is shared across the system and can be run by any shell.

Trying to programmatically execute local as a process will fail - there is no executable with that name; it is purely a shell construct.

So how do we know if a command is a builtin? The preferred method is to use the type command:

$ type local

local is a shell builtin

The type command (which is itself a builtin!) can tell you the exact type of shell command.

Interestingly, you might be using more builtins than you think. echo is a program, but most of the time you are not executing it when you are in a shell:

$ type -a echo

echo is a shell builtin

echo is /bin/echo

By using the -a flag on type to show all commands that match the name, we see that echo is actually both a builtin and a program.

Many simple programs have builtin versions. The shell can execute them much faster.

Some commands are a builtin so that they can function in a sensible manner. The cd command changes the current directory - if we executed it as a process, it would change only the directory for the cd process itself, not the shell, making it much less useful.

Builtins will vary from shell to shell, but many shells are 'Bash-like' - meaning they will have a set very similar to the Bash builtins, which you can see here:

As should be familiar from Part 3: Getting Help, you can get help for builtins:

$ man source # source is a builtin

BUILTIN(1) BSD General Commands Manual BUILTIN(1)

NAME

builtin, !, %, # ...snip...

SYNOPSIS

builtin [-options] [args ...]

However, the manual will not show information on specific builtins, which is a pain. Your shell might have an option to show more details - for example, in Bash you can use help:

$ help source

source: source filename [arguments]

Read and execute commands from FILENAME and return. The pathnames

in $PATH are used to find the directory containing FILENAME. If any

ARGUMENTS are supplied, they become the positional parameters when

FILENAME is executed.

But remember: help is a builtin; you might not find it in all shells (you won't find it in zsh, for example). This highlights again the challenges of builtins.

Functions

You can define your own shell functions. We will see a lot more of this later, but let's show a quick example for now:

$ restart-shell () { exec -l $SHELL }

This snippet creates a function that restarts the shell (quite useful if you are messing with shell configuration files or think you might have irreversibly goofed up your current session).

We can execute this function just like any command:

$ restart-shell

And running type will show us that this is a function:

$ type restart-shell

restart-shell is a function

restart-shell ()

{

exec -l $SHELL

}

Functions are one of the most powerful shell constructs we will see; they are extremely useful for building sophisticated logic. We're going to see them in a lot more detail later, but for now it is enough to know that they exist, and can run logic, and are run as commands.

Aliases

An alias is just a shortcut. Type in a certain set of characters, and the shell will replace them with the value defined in the alias.

Some common commands are actually already aliases - for example, in my zsh shell, the ls command is an alias:

% type -a ls

ls is an alias for ls -G

ls is /bin/ls

I make sure that when I use the ls command, the shell always expands it to ls -G, which colours the output.

We can quickly define aliases to save on keystrokes. For example:

$ alias k='kubectl'

From this point on, I can use the k alias as shorthand for the kubectl command.

Aliases are far less sophisticated than functions. Think of them as keystroke savers and nothing more, and you won't go far wrong.

So What?

So we now hopefully have a greater understanding of the variety of shell commands. Not all commands are executables, not all of the commands we think are executables necessarily are, and some commands might be more sophisticated.

As a shell user, the key things to remember are:

- Executables are 'safe' - they are programs your system can use; your shell just calls out to them.

- Builtins are very shell-specific and usually control the shell itself

- Functions are powerful ways to write logic but will normally be shell-specific.

- Aliases are conveniences for human operators, but only in the context of an interactive shell.

To find out how a command is implemented, just use the type -a command:

$ type -a cat

cat is /bin/cat

More Than You Need to Know

OK, for the masochistic few, you might be wondering about all of the other commands and utilities you may have seen that can tell you about programs and commands:

whatwhatiswhichwhencewherewhereiscommandtype

A lot of these are legacy and should be avoided, but for completeness sake, we'll go through them.

what

what reads out special metadata embedded in a program, generally used to identify the version of source code it was built from:

$ what /bin/ls

/bin/ls

Copyright (c) 1989, 1993, 1994

PROGRAM:ls PROJECT:file_cmds-272.220.1

There should be almost no circumstance in which you need to use it in your day-to-day work, but you might come across it if you meant to type whatis.

whatis

whatis searches a local help database for text. This can be useful in tracking down manual pages:

$ whatis bash

bash(1) - GNU Bourne-Again SHell

bashbug(1) - report a bug in bash

But I can't imagine it will be a regularly used tool by most users.

which

which will search your $PATH to see whether an executable can be found. With the -a flag, it will show all results.

$ which -a vi

/usr/local/bin/vi

/usr/bin/vi

which originated in csh. It remains on many systems for compatibility but in general should be avoided due to potentially odd behaviour.

whence

whence was added to the Korn shell. You are unlikely to use it unless you are on systems using ksh. zsh also has this command, but it should be avoided and considered non-standard.

% whence brew

/usr/local/bin/brew

where

This is a shell builtin that can provide information on commands, similar to type:

% where ls

ls: aliased to ls -G

/bin/ls

However, type should be preferred, as it is more standard.

whereis

whereis is available on some systems and generally operates the same as which, searching paths for an executable:

% whereis ls

/bin/ls

Again, type should be preferred for compatability.

command

command is defined in the POSIX standard, so should be expected to be present on most modern systems. Without arguments, it simply executes a command. With the -v argument, you get a fairly machine-readable or processable response; with the -V argument, you get a more human readable response:

% command -v ls

alias ls='ls -G'

% command -V ls

ls is an alias for ls -G

command can be useful in scripts, as we will see in later chapters.

type

type is part of the Unix standard and will be present in most modern systems. As we've already seen, it will identify the type of command as well as the location for an executable:

% type -a ls

ls is an alias for ls -G

ls is /bin/ls

This command can also be used to only search for paths:

% type -p ls

ls is /bin/ls

Summary

In summary, avoid anything that starts with 'w'! These are legacy commands, generally needed only when working on older Unix machines. type or command should be used instead.

Footnotes