Introduction

In this article, we will discuss the difference between shallow and deep copy in Python.

Simple Copying

Let's look at an example:

lst_first = ['Yesterday', ['we', 'used'], 'the', ['Python', '2']]

lst_second = lst_first

lst_third = lst_first

lst_fourth = lst_first

print("\nOriginal list and three copies of it:")

print("lst_first =", lst_first)

print("lst_second =", lst_second)

print("lst_third =", lst_third)

print("lst_fourth =", lst_fourth)

print("\nLet's change the first word to "Today" and add the word "also"

ONLY at the end of the 4th list...")

lst_fourth [0] = 'Today'

lst_fourth.append('too')

print("\nLet's see the contents of the lists again:")

print("lst_first =", lst_first)

print("lst_second =", lst_second)

print("lst_third =", lst_third)

print("lst_fourth =", lst_fourth)

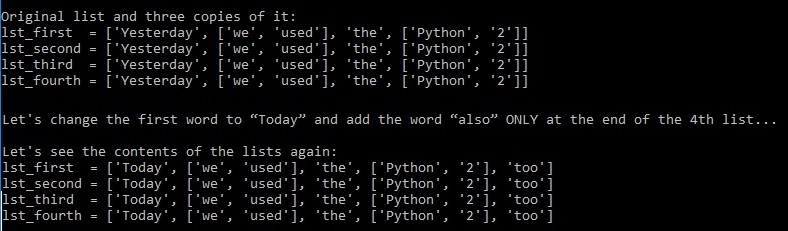

Let's see the output of the above code:

Wow .... We only changed the values in the ‘lst_fourth’ list, but the values in ALL lists changed.

Why?!

In the first line of the script, we create the lst_first list, and then it initializes the other three lists.

After assigning lst_first to the other three lists, all four lists refer to the same memory area.

Later modifications to the content of either are immediately reflected on the contents of ALL other lists.

Let's use the id() built-in Python's function to get the "identity" (unique integer) of each of the list objects:

print()

print("Let's show "identities" (the addresses) of the objects in memory:")

print("id(lst_first) = ", id(lst_first))

print("id(lst_second) = ", id(lst_second))

print("id(lst_third) = ", id(lst_third))

print("id(lst_fourth) = ", id(lst_fourth))

The result for the above example would be something like this:

We can see that the value returned by the id() function for DIFFERENT OBJECTS is the SAME!

This confirms the above, that ALL four objects of list refer to the SAME address space!

Schematically, it looks like this:

It is clear that for the actual copying of lists, we need to use a different way.

Let's try another approach to create independent lists...

Shallow Copy

The following example illustrates 3 different ways to create a shallow copy:

import copy

lst_first = ['Yesterday', ['we', 'used'], 'the', ['Python', '2']]

lst_second = copy.copy(lst_first)

lst_third = list(lst_first)

lst_fourth = lst_first[:]

print("\nOriginal list and three copies of it:")

print("lst_first =", lst_first)

print("lst_second =", lst_second)

print("lst_third =", lst_third)

print("lst_fourth =", lst_fourth)

print()

print("Let's show "identities" (the addresses) of the objects in memory:")

print("id(lst_first) = ", id(lst_first))

print("id(lst_second) = ", id(lst_second))

print("id(lst_third) = ", id(lst_third))

print("id(lst_fourth) = ", id(lst_fourth))

Now let's look at the result of the program:

OK. As we can see, all lists (lst_second, lst_third and lst_fourth) store the same values as the original list (lst_first).

However, the obtained values of the id() function for each of the four lists show DIFFERENT values.

This means that this time, each list's object has its own, independent address space.

Note

- To copy to

lst_second, the 'copy' function of the 'copy module' provides generic shallow copy operation. - The

list() takes sequence of lst_first object and converts it to lst_third list. The list() constructor returns a mutable sequence list of elements. - Shallow copies of lists can be made by assigning a slice of the entire list, for example,

lst_fourth = lst_first[:]. Here, the lst_first list return a new list containing the requested elements. This means that the above slice operator returns a copy of the list, where all elements will be duplicated into lst_fourth list (i.e., to another area in memory).

Great!

Now everything works as we expected. All three methods created independent address spaces.

Now let's modify the elements of the above lists, adding more specific information to the created lists:

lst_first [0] = 'In 2014'

lst_first.append(".7.9")

lst_second[0] = 'In 2015'

lst_second.append(".7.10")

lst_third [0] = 'In 2016'

lst_third.append(".7.13")

lst_fourth [0] = 'In 2017'

lst_fourth.append(".7.14")

print("\nLists after modification:")

print("lst_first =", lst_first)

print("lst_second =", lst_second)

print("lst_third =", lst_third)

print("lst_fourth =", lst_fourth)

And run the code:

Well, it worked really well, didn't it?

As expected, each list contains its own historical data on the use of Python releases.

But for now, however, let's inform the user that a new release, Python 3.8, was released on October 14th, 2019.

For this purpose, we will change the content of only ONE of the lists.

lst_fourth [0] = 'From October 14th, 2019'

lst_fourth [1][1] = 'are using'

lst_fourth [2] = 'a new release is'

lst_fourth [3][1] = '3.8'

lst_fourth.remove('.7.14')

print("\nLet's see ALL the lists again, after modifying the 'lst_fourth' list:")

print("lst_first =", lst_first)

print("lst_second =", lst_second)

print("lst_third =", lst_third)

print("lst_fourth =", lst_fourth)

Now let's run the script again to see what the last 4 lines print:

Ops..... This is not at all what we expected to see!

We expected to see changes only in ‘lst_fourth’, but all lists changed!!!

Why were the values added in all the lists?

The 'lst_first' list contained three elements and two pointers to other (internal) lists, which look like this: ['we', 'used'] and ['Python', '2']. When we did a shallow copy of lst_first to create the lists, then only simple string elements were duplicated, but NOT compound objects (our lists). A shallow copy constructed a new list and then inserted simple strings objects and references into it to the compound objects found in the original. So, that all these references pointing to SAME address space (i.e., pointers were cloned, and NOT the address spaces to which these pointers referred) As a result, 'lst_first', 'lst_second', 'lst_third' and 'lst_fourth' lists are stored in separate address spaces, but at the same time, pointers to internal lists refer to ONE address. The problem arises whenever someone modifies "their" internal lists, because this change will affect the contents of ALL internal lists.

Schematically, it looks like this:

Deep Copy

Clearly, we need a different approach when creating object clones to force Python to make a full copy of ALL the list's elements (simple and compound objects) that are contained in the list and its sublists or objects?

The cure for the problems of copying ALL list items is to make a deep copy!

That is, rather than just copy the address of the compound objects, we need to force Python to make a full copy of ALL the list's elements (simple and compound objects).That way, each object gets its address space rather than refer to one common object.

Let's see how deep copying is performed by using the deepcopy () function:

import copy

lst_first = ['Yesterday', ['we', 'used'], 'the', ['Python', '2']]

lst_second = copy.deepcopy(lst_first)

lst_third = copy.deepcopy(lst_first)

lst_fourth = copy.deepcopy(lst_first)

print("\nOriginal list and three copies of it:")

print("lst_first =", lst_first)

print("lst_second =", lst_second)

print("lst_third =", lst_third)

print("lst_fourth =", lst_fourth)

print()

print("Let's show "identities" (the addresses) of the objects in memory:")

print("id(lst_first) = ", id(lst_first))

print("id(lst_second) = ", id(lst_second))

print("id(lst_third) = ", id(lst_third))

print("id(lst_fourth) = ", id(lst_fourth))

lst_fourth [0] = 'From October 14th, 2019'

lst_fourth [1][1] = 'are using'

lst_fourth [2] = 'a new release is'

lst_fourth [3][1] = '3.8'

lst_fourth.remove('.7.14')

print("\nLet's see ALL the lists again, after modifying the 'lst_fourth' list:")

print("lst_first =", lst_first)

print("lst_second =", lst_second)

print("lst_third =", lst_third)

print("lst_fourth =", lst_fourth)

Let's look at the output of the above code:

Schematically, it looks like this:

Summary

Instead of a summary, I will provide what is written in the Python documentation here:

“The difference between shallow and deep copying is only relevant for compound objects (objects that contain other objects, like lists or class instances):

- A shallow copy constructs a new compound object and then (to the extent possible) inserts references into it to the objects found in the original.

- A deep copy constructs a new compound object and then, recursively, inserts copies into it of the objects found in the original.”

History

- 23rd November, 2019: Initial version