In a large system, main() can easily become a mess as different developers add their initialization code. This article presents a Module class that allows a system to be initialized in a structured, layered manner. It then evolves the design to show how the system can perform a quick restart, rather than a reboot, to recover from serious errors such as trampled memory.

Introduction

In many C++ programs, the main function #includes the world and utterly lacks structure. This article describes how to initialize a system in a structured manner. It then discusses how to evolve the design to support recovery from serious errors (usually corrupted memory) by quickly reinitializing a subset of the system instead of having to reboot its executable.

Using the Code

The code in this article is taken from the Robust Services Core (RSC). If this is the first time that you're reading an article about an aspect of RSC, please take a few minutes to read this preface.

Initializing the System

We'll start by looking at how RSC initializes when the system boots up.

Module

Each Module subclass represents a set of interrelated source code files that provides some logical capability.1 Each of these subclasses is responsible for

- instantiating the modules on which it depends (in its constructor)

- enabling the modules on which it depends (in its

Enable function) - initializing the set of source code files that it represents when the executable is launched (in its

Startup function)

Each Module subclass currently corresponds 1-to-1 with a static library. This has worked well and is therefore unlikely to change. Dependencies between static libraries must be defined before building an executable, so it's easy to apply the same dependencies among modules. And since no static library is very large, each module can easily initialize the static library to which it belongs.

Here's the outline of a typical module:

class SomeModule : public Module

{

friend class Singleton<SomeModule>;

private:

SomeModule() : Module("sym") {

Singleton<Module1>::Instance();

Singleton<ModuleN>::Instance();

Singleton<ModuleRegistry>::Instance()->BindModule(*this);

}

~SomeModule() = default;

void Enable() override

{

Singleton<Module1>::Instance()->Enable();

Singleton<ModuleN>::Instance()->Enable();

Module::Enable();

}

void Startup() override; };

If each module's constructor instantiates the modules on which it depends, how are leaf modules created? The answer is that main creates them. The code for main will appear soon.

Enabling Modules

The latest change to the module framework means that instantiating a module no longer leads to the invocation of its Startup function. A module must now also be enabled before its Startup function will be invoked.

In the same way that a module's constructor instantiates the modules that it requires, its Enable function enables those modules, and also itself. This raises a similar question: how are leaf modules enabled? The answer is that when a leaf module invokes the base class Module constructor, it must provide a symbol that uniquely identifies it. The leaf module can then be enabled by including this symbol in the configuration parameter OptionalModules, which is found in the configuration file.

Why add a separate step to enable a module that is already in the build? The answer is that a product could have many optional subsystems, each supported by one or more modules. In some cases, the product might be deployed for a specific role that only requires one set of modules. In other cases, the product might fulfill several roles, such that several sets of modules are required. Having to create a unique build for each possible combination of roles is an administrative burden. This burden can be avoided by delivering a single, superset build that combines all roles. The desired subset of roles can then be enabled by using the OptionalModules configuration parameter to enable the modules that are actually required. And if the customer later decides that a different set of roles is needed, this can be achieved by simply updating the configuration parameter and rebooting the system.

As an example, consider the Internet. The IETF defines numerous application layer protocols that support various roles. In a large network, a product that supports many of those protocols might be deployed as a dedicated Border Gateway Router. But in a small network, the product might also act as a DNS server, mail server (SMTP), and call server (SIP).

ModuleRegistry

The singleton ModuleRegistry appeared in the last line of the above constructor. It contains all of the system's modules, sorted by their dependencies (a partial ordering). ModuleRegistry also has a Startup function that initializes the system by invoking Startup on each enabled module.

Thread, RootThread, and InitThread

In RSC, each thread derives from the base class Thread, which encapsulates a native thread and provides a variety of functions related to things like exception handling, scheduling, and inter-thread communication.

The first thread that RSC creates is RootThread, which is soon created by the thread that the C++ run-time system created to run main. RootThread simply brings the system up to the point where it can create the next thread. That thread, InitThread, is responsible for initializing most of the system. Once initialization is complete, InitThread acts as a watchdog to ensure that threads are being scheduled, and RootThread acts as a watchdog to ensure that InitThread is running.

main()

After it echoes and saves the command line arguments, main simply instantiates leaf modules. RSC currently has 15 static libraries and, therefore, 15 modules. Modules that are instantiated transitively, via the constructors of these modules, do not need to be instantiated by main:

main_t main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

std::cout << "ROBUST SERVICES CORE" << CRLF;

MainArgs::EchoAndSaveArgs(argc, argv);

CreateModules();

return RootThread::Main();

}

static void CreateModules()

{

Singleton<CtModule>::Instance();

Singleton<OnModule>::Instance();

Singleton<CnModule>::Instance();

Singleton<RnModule>::Instance();

Singleton<SnModule>::Instance();

Singleton<AnModule>::Instance();

Singleton<DipModule>::Instance();

}

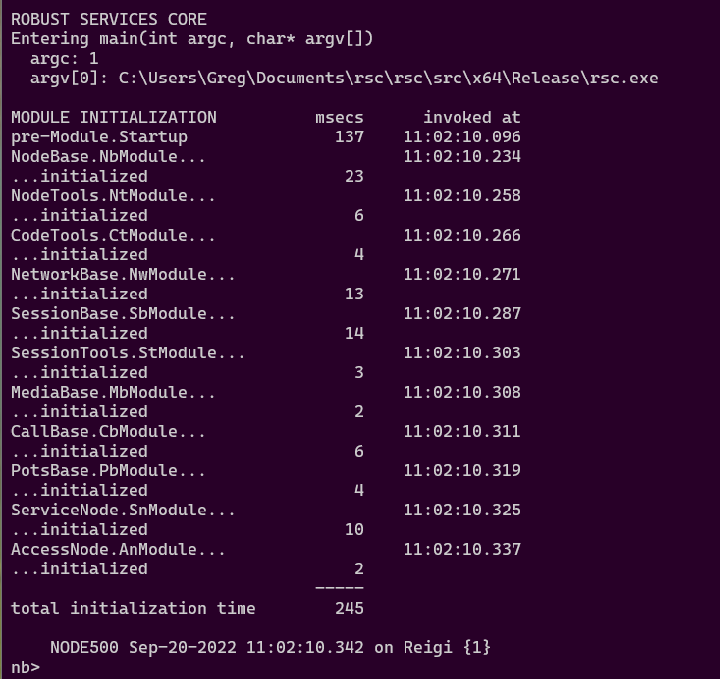

Once the system has initialized, entering the >modules command on the CLI displays the following, which is the order in which enabled modules were invoked to initialize their static libraries:

If an application built on RSC does not require a particular static library, the instantiation of its module can be commented out, and the linker will exclude all of that library's code from the executable. Even if the library's module is instantiated, it can still be disabled by excluding its symbol from the OptionalModules configuration parameter.

main is the only code implemented outside a static library. It resides in the rsc directory, whose only source code file is main.cpp. All other software, whether part of the framework or an application, resides in a static library.

RootThread::Main

The last thing that main did was invoke RootThread::Main, which is a static function because RootThread has not yet been instantiated. Its job is to create the things that are needed to actually instantiate RootThread:

main_t RootThread::Main()

{

SysStackTrace::Startup(RestartReboot);

CreatePosixSignals();

Singleton<LogBufferRegistry>::Instance();

SysThread::ConfigureProcess();

Singleton<ThreadRegistry>::Instance();

Singleton<RootThread>::Instance();

ExitGate().WaitFor(TIMEOUT_NEVER);

Debug::Exiting();

exit(ExitCode);

}

Creating the RootThread singleton leads to the invocation of RootThread::Enter, which implements RootThread's thread loop. RootThread::Enter creates InitThread, whose first task is to finish initializing the system. RootThread then goes to sleep, running a watchdog timer that is cancelled when InitThread interrupts RootThread to tell it that the system has been initialized. If the timer expires, the system failed to initialize: it is embarrassingly dead on arrival, so RootThread exits, which causes RootThread::Main to invoke exit.

ModuleRegistry::Startup

To finish initializing the system, InitThread invokes ModuleRegistry::Startup. This function invokes each module's Startup function. It also records how long it took to initialize each module, code that has been deleted for clarity:

void ModuleRegistry::Startup(RestartLevel level) {

for(auto m = modules_.First(); m != nullptr; modules_.Next(m))

{

if(m->IsEnabled())

{

m->Startup(level);

}

}

}

Once this function is finished, something very similar to this will have appeared on the console:

A Module::Startup Function

Module Startup functions aren't particularly interesting. One of RSC's design principles is that objects needed to process user requests should be created during system initialization, so as to provide predictable latency once the system is in service. Here is the Startup code for NbModule, which initializes the namespace NodeBase:

void NbModule::Startup(RestartLevel level)

{

Singleton<PosixSignalRegistry>::Instance()->Startup(level);

Singleton<LogBufferRegistry>::Instance()->Startup(level);

Singleton<ThreadRegistry>::Instance()->Startup(level);

Singleton<StatisticsRegistry>::Instance()->Startup(level);

Singleton<AlarmRegistry>::Instance()->Startup(level);

Singleton<LogGroupRegistry>::Instance()->Startup(level);

CreateNbLogs(level);

Singleton<CfgParmRegistry>::Instance()->Startup(level);

Singleton<DaemonRegistry>::Instance()->Startup(level);

Singleton<DeferredRegistry>::Instance()->Startup(level);

Singleton<ObjectPoolRegistry>::Instance()->Startup(level);

Singleton<ThreadAdmin>::Instance()->Startup(level);

Singleton<MsgBufferPool>::Instance()->Startup(level);

Singleton<ClassRegistry>::Instance()->Startup(level);

Singleton<Element>::Instance()->Startup(level);

Singleton<CliRegistry>::Instance()->Startup(level);

Singleton<SymbolRegistry>::Instance()->Startup(level);

Singleton<NbIncrement>::Instance()->Startup(level);

Singleton<FileThread>::Instance()->Startup(level);

Singleton<CoutThread>::Instance()->Startup(level);

Singleton<CinThread>::Instance()->Startup(level);

Singleton<ObjectPoolAudit>::Instance()->Startup(level);

Singleton<StatisticsThread>::Instance()->Startup(level);

Singleton<LogThread>::Instance()->Startup(level);

Singleton<DeferredThread>::Instance()->Startup(level);

Singleton<CliThread>::Instance()->Startup(level);

Singleton<ModuleRegistry>::Instance()->EnableModules();

}

Before it returns, NbModule::Startup enables the modules in the OptionalModules configuration parameter. It can do this because NodeBase is RSC's lowest layer, so NbModule::Startup is always invoked.

Restarting the System

So far, we have an initialization framework with the following characteristics:

- a structured and layered approach to initialization

- a simple

main that only needs to create leaf modules - ease of excluding a static library from the build by not instantiating the module that initializes it

- ease of customizing a superset load by enabling only the modules needed to fulfill its role(s)

We will now enhance this framework so that we can reinitialize the system to recover from serious errors. Robust C++: Safety Net describes how to do this for an individual thread. But sometimes a system gets into a state where the types of errors described in that article recur. In such a situation, more drastic action is required. Quite often, some data has been corrupted, and fixing it will restore the system to health. A partial reinitialization of the system, short of a complete reboot, can often do exactly that.

If we can initialize the system in a layered manner, we should also be able to shut it down in a layered manner. We can define Shutdown functions to complement the Startup functions that we've already seen. However, we only want to perform a partial shutdown, followed by a partial startup to recreate the things that the shutdown phase destroyed. If we can do that, we will have achieved a partial reinitialization.

But what, exactly, should we destroy and recreate? Some things are easily recreated. Other things will take much longer, during which time the system will be unavailable. It is therefore best to use a flexible strategy. If the system is in trouble, start by reinitializing what can be recreated quickly. If that doesn't fix the problem, broaden the scope of what gets reinitialized, and so on. Eventually, we'll have to give up and reboot.

Our restart (reinitialization) strategy therefore escalates. RSC supports three levels of restart whose scopes are less than a full reboot. When the system gets into trouble, it tries to recover by initiating the restart with the narrowest scope. But if it soon gets into trouble again, it increases the scope of the next restart:

- A warm restart destroys temporary data and also exits and recreates as many threads as possible. Any user request currently being processed is lost and must be resubmitted.

- A cold restart also destroys dynamic data, which is data that changes while processing user requests. All sessions, for example, are lost and must be reinitiated.

- A reload restart also destroys data that is relatively static, such as configuration data that user requests rarely modify. This data is usually loaded from disk or over the network, two examples being an in-memory database of user profiles and another of images that are included in server-to-client HTTP messages.

Startup and Shutdown functions therefore need a parameter that specifies what type of restart is occurring:

enum RestartLevel

{

RestartNil, RestartWarm, RestartCold, RestartReload, RestartReboot, RestartExit, RestartLevel_N };

Initiating a Restart

A restart occurs as follows:

- The code which decides that a restart is required invokes

Restart::Initiate. Restart::Initiate throws an ElementException.Thread::Start catches the ElementException and invokes InitThread::InitiateRestart.InitThread::InitiateRestart interrupts RootThread to tell it that a restart is about to begin and then interrupts itself to initiate the restart.- When

InitThread is interrupted, it invokes ModuleRegistry::Restart to manage the restart. This function contains a state machine that steps through the shutdown and startup phases by invoking ModuleRegistry::Shutdown (described below) and ModuleRegistry::Startup (already described). - When

RootThread is interrupted, it starts a watchdog timer. When the restart is completed, InitThread interrupts RootThread, which cancels the timer. If the timer expires, RootThread forces InitThread to exit and recreates it. When InitThread is reentered, it invokes ModuleRegistry::Restart again, which escalates the restart to the next level.

Deleting Objects During a Restart

Because the goal of a restart is to reinitialize a subset of the system as quickly as possible, RSC takes a drastic approach. Rather than delete objects one at a time, it simply frees the heap from which they were allocated. In a system with tens of thousands of sessions, for example, this dramatically speeds up the time required for a cold restart. The drawback is that it adds some complexity because each type of memory requires its own heap:

MemoryType | Base Class | Attributes |

MemTemporary | Temporary | does not survive any restart |

MemDynamic | Dynamic | survives warm restarts but not cold or reload restarts |

MemSlab | Pooled | survives warm restarts but not cold or reload restarts |

MemPersistent | Persistent | survives warm and cold restarts but not reload restarts |

MemProtected | Protected | write-protected; survives warm and cold restarts but not reload restarts |

MemPermanent | Permanent | survives all restarts (this is a wrapper for the C++ default heap) |

MemImmutable | Immutable | write-protected; survives all restarts (similar to C++ global const data) |

To use a given MemoryType, a class derives from the corresponding class in the Base Class column. How this works is described later.

A Module::Shutdown Function

A module's Shutdown function closely resembles its Startup function. It invokes Shutdown on objects within its static library, but in the opposite order to which it invoked their Startup functions. Here is the Shutdown function for NbModule, which is (more or less) a mirror image of its Startup function that appeared earlier:

void NbModule::Shutdown(RestartLevel level)

{

Singleton<NbIncrement>::Instance()->Shutdown(level);

Singleton<SymbolRegistry>::Instance()->Shutdown(level);

Singleton<CliRegistry>::Instance()->Shutdown(level);

Singleton<Element>::Instance()->Shutdown(level);

Singleton<ClassRegistry>::Instance()->Shutdown(level);

Singleton<ThreadAdmin>::Instance()->Shutdown(level);

Singleton<ObjectPoolRegistry>::Instance()->Shutdown(level);

Singleton<DeferredRegistry>::Instance()->Shutdown(level);

Singleton<DaemonRegistry>::Instance()->Shutdown(level);

Singleton<CfgParmRegistry>::Instance()->Shutdown(level);

Singleton<LogGroupRegistry>::Instance()->Shutdown(level);

Singleton<AlarmRegistry>::Instance()->Shutdown(level);

Singleton<StatisticsRegistry>::Instance()->Shutdown(level);

Singleton<ThreadRegistry>::Instance()->Shutdown(level);

Singleton<LogBufferRegistry>::Instance()->Shutdown(level);

Singleton<PosixSignalRegistry>::Instance()->Shutdown(level);

Singleton<TraceBuffer>::Instance()->Shutdown(level);

SysThreadStack::Shutdown(level);

Memory::Shutdown();

Singletons::Instance()->Shutdown(level);

}

Given that a restart frees one or more heaps rather than expecting objects on those heaps to be deleted, what is the purpose of a Shutdown function? The answer is that an object which survives the restart might have pointers to objects that will be destroyed or recreated. Its Shutdown needs to clear such pointers.

NbModule's Startup function created a number of threads, so how come its Shutdown function doesn't shut them down? The reason is that ModuleRegistry::Shutdown handles this earlier in the restart.

ModuleRegistry::Shutdown

This function first allows a subset of threads to run for a while so that they can generate any pending logs. It then notifies all threads of the restart, counting how many of them are willing to exit, and then schedules them until they have exited. Finally, it shuts down all modules in the opposite order that their Startup functions were invoked. As with ModuleRegistry::Startup, code that logs the progress of the restart has been deleted for clarity:

void ModuleRegistry::Shutdown(RestartLevel level)

{

if(level >= RestartReload)

{

Memory::Unprotect(MemProtected);

}

msecs_t delay(25);

Thread::EnableFactions(ShutdownFactions());

for(size_t tries = 120, idle = 0; (tries > 0) && (idle <= 8); --tries)

{

ThisThread::Pause(delay);

if(Thread::SwitchContext() != nullptr)

idle = 0;

else

++idle;

}

Thread::EnableFactions(NoFactions);

auto reg = Singleton<ThreadRegistry>::Instance();

auto exiting = reg->Restarting(level);

auto target = exiting.size();

for(auto t = exiting.cbegin(); t != exiting.cend(); ++t)

{

(*t)->Raise(SIGCLOSE);

}

Thread::EnableFactions(AllFactions());

{

for(auto prev = exiting.size(); prev > 0; prev = exiting.size())

{

Thread::SwitchContext();

ThisThread::Pause(delay);

reg->TrimThreads(exiting);

if(prev == exiting.size())

{

for(auto t = exiting.cbegin(); t != exiting.cend(); ++t)

{

(*t)->Raise(SIGCLOSE);

}

}

}

}

Thread::EnableFactions(NoFactions);

for(auto m = modules_.Last(); m != nullptr; modules_.Prev(m))

{

if(m->IsEnabled())

{

m->Shutdown(level);

}

}

}

Shutting Down a Thread

ModuleRegistry::Shutdown (via ThreadRegistry) invokes Thread::Restarting to see if a thread is willing to exit during the restart. This function, in turn, invokes the virtual function ExitOnRestart:

bool Thread::Restarting(RestartLevel level)

{

if(ExitOnRestart(level)) return true;

if(faction_ < SystemFaction) priv_->action_ = SleepThread;

return false;

}

The default implementation of ExitOnRestart is:

bool Thread::ExitOnRestart(RestartLevel level) const

{

if(faction_ >= SystemFaction) return false;

if(priv_->blocked_ == BlockedOnStream) return false;

return true;

}

A thread that is willing to exit receives the signal SIGCLOSE. Before it delivers this signal, Thread::Raise invokes the virtual function Unblock on the thread in case it is currently blocked. For example, each instance of UdpIoThread receives UDP packets on an IP port. Because pending user requests are supposed to survive warm restarts, UdpIoThread overrides ExitOnRestart to return false during a warm restart. During other types of restarts, it returns true, and its override of Unblock sends a message to its socket so that its call to recvfrom will immediately return, allowing it to exit.

Supporting Memory Types

This section discusses what is needed to support a MemoryType, each of which has its own persistence and protection characteristics.

Heaps

Each MemoryType requires its own heap so that all of its objects can be deleted en masse by simply freeing that heap during the appropriate types of restart. The default heap is platform specific, so RSC defines SysHeap to wrap it. Although this heap is never freed, wrapping it allows memory usage by objects derived from Permanent to be tracked.

To support write-protected memory on Windows, RSC had to implement its own heap, because the custom heap provided by Windows, for some undisclosed reason, soon fails if it is write-protected. Consequently, there is now a base class, Heap, with three subclasses:

SysHeap, already mentioned, which wraps the default C++ heap and supports MemPermanent.BuddyHeap, an instance of which supports all but MemPermanent and MemSlab. Each is a fixed-size heap (though the size is configurable) that is implemented using buddy allocation and that can be write-protected.SlabHeap, which supports MemSlab. This is an expandable heap intended for applications that rarely, if ever, free memory after they allocate it. Object pools use this heap so they can grow to handle higher than anticipated workloads.

The interface Memory.h is used to allocate and free the various types of memory. Its primary functions are similar to malloc and free, with the various heaps being private to Memory.cpp:

void* Alloc(size_t size, MemoryType type);

void* Alloc(size_t size, MemoryType type, std::nothrow_t&);

void Free(void* addr, MemoryType type);

Base Classes

A class whose objects can be allocated dynamically derives from one of the classes mentioned previously, such as Dynamic. If it doesn't do so, its objects are allocated from the default heap, which is equivalent to deriving from Permanent.

The base classes that support the various memory types simply override operator new and operator delete to use the appropriate heap. For example:

void* Dynamic::operator new(size_t size)

{

return Memory::Alloc(size, MemDynamic);

}

void* Dynamic::operator new[](size_t size)

{

return Memory::Alloc(size, MemDynamic);

}

void Dynamic::operator delete(void* addr)

{

Memory::Free(addr, MemDynamic);

}

void Dynamic::operator delete[](void* addr)

{

Memory::Free(addr, MemDynamic);

}

Allocators

A class with a std::string member wants the string to allocate memory from the same heap that is used for objects of that class. If the string instead allocates memory from the default heap, a restart will leak memory when the object's heap is freed. Although the restart will free the memory used by string object itself, its destructor is not invoked, so the memory that it allocated to hold its characters will leak.

RSC therefore provides a C++ allocator for each MemoryType so that a class whose objects are not allocated on the default heap can use classes from the standard library. These allocators are defined in Allocators.h and are used to define STL classes that allocate memory from the desired heap. For example:

typedef std::char_traits<char> CharTraits;

typedef std::basic_string<char, CharTraits, DynamicAllocator<char>> DynamicStr;

A class derived from Dynamic then uses DynamicStr to declare what would normally have been a std::string member.

Write-Protecting Data

The table of memory types noted that MemProtected is write-protected. The rationale for this is that data which is only deleted during a reload restart is expensive to recreate, because it must be loaded from disk or over the network. The data also changes far less frequently than other data. It is therefore prudent but not cost-prohibitive to protect it from trampling.

During system initialization, MemProtected is unprotected. Just before it starts to handle user requests, the system write-protects MemProtected. Applications must then explicitly unprotect and reprotect it in order to modify data whose memory was allocated from its heap. Only during a reload restart is it again unprotected, while recreating this data.

A second type of write-protected memory, MemImmutable, is defined for the same reason. It contains critical data that should never change, such as the Module subclasses and ModuleRegistry. Once the system has initialized, it is permanently write-protected so that it cannot be trampled.

When the system is in service, protected memory must be unprotected before it can be modified. Forgetting to do this causes an exception that is almost identical to the one caused by a bad pointer. Because the root causes of these exceptions are very different, RSC distinguishes them by using a proprietary POSIX signal, SIGWRITE, to denote writing to protected memory, rather than the usual SIGSEGV that denotes a bad pointer.

After protected memory has been modified, say to insert a new subscriber profile, it must be immediately reprotected. The stack object FunctionGuard is used for this purpose. Its constructor unprotects memory and, when it goes out of scope, its destructor automatically reprotects it:

FunctionGuard guard(Guard_MemUnprotect);

return;

There is also a far less frequently used Guard_ImmUnprotect for modifying MemImmutable. The FunctionGuard constructor invokes a private Thread function that eventually unprotects the memory in question. The function is defined by Thread because each thread has an unprotection counter for both MemProtected and MemImmutable. This allows unprotection events to be nested and a thread's current memory protection attributes to be restored when it is scheduled in.

Designing a Class that Mixes Memory Types

Not all classes will be satisfied with using a single MemoryType. RSC's configuration parameters, for example, derive from Protected, but its statistics derive from Dynamic. Some classes want to include members that support both of these capabilities.

Another example is a subscriber profile, which would usually derive from Protected. But it might also track a subscriber's state, which changes too frequently to be placed in write-protected memory and would therefore reside outside the profile, perhaps in Persistent memory.

Here are some guidelines for designing classes with mixed memory types:

- If a class embeds another class directly, rather than allocating it through a pointer, that class resides in the same

MemoryType as its owner. If the embedded class allocates memory of its own, however, it must use the same MemoryType as its owner. This was previously discussed in conjunction with strings. - If a class wants to write-protect most of its data but also has data that changes too frequently, it should use the PIMPL idiom to allocate its more dynamic data in a

struct that usually has the same persistence. That is, a class derived from Protected puts its dynamic data in a struct derived from Persistent, and a class derived from Immutable puts its dynamic data in a struct derived from Permanent. This way, the primary class and its associated dynamic data either survive a restart or get destroyed together.2 - If a class needs to include a class with different persistence, it should manage it through a

unique_ptr and override the Shutdown and Startup functions discussed earlier:

- If the class owns an object of lesser persistence, its

Shutdown function invokes unique_ptr::release to clear the pointer to that object if the restart will destroy it. When its Startup function notices the nullptr, it reallocates the object. - If the class owns an object of greater persistence, its

Shutdown function may invoke unique_ptr::reset to prevent a memory leak during a restart that destroys the owner. But if it can find the object, it doesn't need to do anything. When it is recreated during the restart's startup phase, its constructor must not blindly create the object of greater persistence. Instead, it must first try to find it, usually in a registry of such objects. This is the more likely scenario; the object was designed to survive the restart, so it should be allowed to do so.

Writing Shutdown and Startup Functions

There are a few functions that many Shutdown and Startup functions use. Base::MemType returns the type of memory that a class uses, and Restart::ClearsMemory and Restart::Release use its result:

enum MemoryType

{

MemNull, MemTemporary, MemDynamic, MemSlab, MemPersistent, MemProtected, MemPermanent, MemImmutable, MemoryType_N };

virtual MemoryType MemType() const;

static bool ClearsMemory(MemoryType type);

template<class T> static bool Release(std::unique_ptr< T >& obj)

{

auto type = (obj == nullptr ? MemNull : obj->MemType());

if(!ClearsMemory(type)) return false;

obj.release();

return true;

}

Automated Rebooting

If the sequence of warm, cold, and reload restarts fails to restore the system to sanity, the restart escalates to a RestartReboot. To support automated rebooting, RSC must be launched using the simple Launcher application whose source code resides in the launcher directory. An RSC build produces both an rsc.exe and a launcher.exe.

When Launcher starts up, it simply asks for the directory that contains the rsc.exe that it will create as a child process, as well as any extra command line parameters for rsc.exe. It then launches rsc.exe and goes to sleep, waiting for it to exit. To initiate a reboot, RSC exits with a non-zero exit code, which causes Launcher to immediately recreate it.

When Launcher is used to launch RSC, the CLI command >restart exit must be used to shut down RSC gracefully. It causes RSC to exit with an exit code of 0, which prevents Launcher from immediately recreating it.

Traces of the Code in Action

RSC's output directory contains console transcripts (*.console.txt), log files (*.log.txt), and function traces (*.trace.txt) of the following:

- system initialization, in the files init.*

- a warm restart, in the files warm* (warm1.* and warm2.* are pre- and post-restart, respectively)

- a cold restart, in the files cold* (cold1.* and cold2.* are pre- and post-restart, respectively)

- a reload restart, in the files reload* (reload1.* and reload2.* are pre- and post-restart, respectively)

The restarts were initiated using the CLI's >restart command.

Notes

1 The term module, as used in this article, is unrelated to modules as introduced in C++20. The term isn't going to be changed just because C++ also later started to use it.

2 RSC uses the PIMPL idiom in this way in several places: just look for any member named dyn_.

History

- 20th September, 2022: Updated to reflect support for selectively enabling modules.

- 29th March, 2022: Added section on automated rebooting.

- 4th May, 2020: Updated to reflect support for reload restarts and write-protected memory; added section on designing a class that mixes memory types

- 23rd December, 2019: Initial version