We’ll introduce the oneAPI software model and then discuss the compilation model and the binary generation procedure. oneAPI provides a single binary for all architectures, so the compile and link steps are different from normal methods of binary generation. Finally, we’ll examine some sample programs. Note that we use the terms accelerator, target, and device interchangeably throughout this article.

Getting the maximum achievable performance out of today’s hardware is a fine balance between optimal use of underlying hardware features and using code that is portable, easily maintainable, and power-efficient. These factors don't necessarily work in tandem. They require prioritizing based on user needs. It's non-trivial for users to maintain separate code bases for different architectures. A standard, simplified programming model that can run seamlessly on scalar, vector, matrix, and spatial architectures will give developers greater productivity through increased code reuse and reduced training investment.

oneAPI is an industry initiative designed to deliver these benefits. It’s based on standards and open specifications and includes the Data Parallel C++ (DPC++) language as well as a set of domain libraries. The goal of oneAPI is for hardware vendors across the industry to develop their own compatible implementations targeting their CPUs and accelerators. That way, developers only need to code in a single language and set of library APIs across multiple architectures and multiple vendor devices.

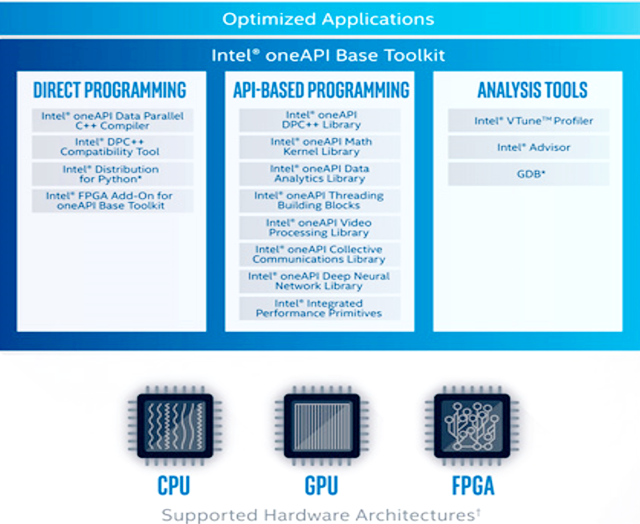

The Intel beta oneAPI developer tools implementation, targeting Intel® CPUs and accelerators, consists of the Intel® oneAPI Base Toolkit along with multiple domain specific toolkits—Intel® HPC, IoT, DL Framework Developer, and Rendering toolkits—which cater to different users.

Figure 1 shows the different layers that are part of the beta Intel oneAPI product and the Base Toolkit, which consists of the Intel oneAPI DPC++ Compiler, the Intel® DPC++ Compatibility Tool, multiple optimized libraries, and advanced analysis and debugging tools. Parallelism across architectures is expressed using the DPC++ language, which is based on SYCL* from Khronos Group. It uses modern C++ features along with Intel-specific extensions for efficient architecture usage. DPC++ language features allow code to be run on the CPU and to be offloaded onto an available accelerator—making it possibled to reuse code. A fallback property allows the code to be run on the CPU when an accelerator isn't available. The execution on the host and accelerator, along with the memory dependencies, are clearly defined.

Users can also port their codes from CUDA* to DPC++ using the Intel DPC++ Compatibility Tool. It assists developers with a one-time migration and typically migrates 80 to 90% of the code automatically.

In addition to DPC++, the Intel oneAPI HPC Toolkit supports OpenMP* 5.0 features that allow code to be offloaded onto a GPU. Users can either transition to using DPC++ or make use of the offload features on their existing C/C++/Fortran code. API-based programming is supported through a set of libraries (e.g., the Intel® oneAPI Math Kernel Library), which will be optimized for Intel GPUs.

The beta Intel oneAPI product also offers new features in Intel® VTune™ Profiler1 and Intel® Advisor2, which allow users to debug their code and look at performance-related metrics when code is offloaded onto an accelerator.

Components of the Beta Intel® oneAPI Base toolkit

This article introduces the beta release of the oneAPI product to facilitate heterogeneous programming. We’ll introduce the oneAPI software model and then discuss the compilation model and the binary generation procedure. oneAPI provides a single binary for all architectures, so the compile and link steps are different from normal methods of binary generation. Finally, we’ll examine some sample programs. Note that we use the terms accelerator, target, and device interchangeably throughout this article.

oneAPI Software Model

The oneAPI software model, based on the SYCL specification, describes the interaction between the host and device in terms of code execution and memory usage. The model has four parts: For more complete information about compiler optimizations, see our Optimization Notice. Sign up for future issues

- A platform model specifying the host and device

- An execution model specifying the command queues and the commands that will be run on the device

- A memory model specifying memory usage between the host and device

- A kernel model that targets computational kernels to devices

Platform Model

The oneAPI platform model specifies the host and multiple devices that communicate with each other or the host. The host controls the execution of kernels on the devices and coordinates among them if there are multiple devices. Each device can have multiple compute units. And each compute unit can have multiple processing elements. The oneAPI specification can support multiple devices like GPUs, FPGAs, and ASICs as long as the platform satisfies the minimum requirements of the oneAPI software model. This typically means the hosts need to have a specific operating system, a specific GNU* GCC version, and certain drivers needed by the devices. (See the release notes for each oneAPI component for details on the platform requirements.)

Execution Model

The oneAPI execution model specifies how the code is executed on the host and device. The host execution model creates command groups to coordinate the execution of kernels and data management between host and devices. The command groups are submitted in queues that can be run with either an in-order or out-of-order policy. Commands within a queue can be synchronized to ensure data updates on the device are available to the host before the next command is executed.

The device execution model specifies how the computation is done on the accelerator. The execution ranges over a set of elements that can either be a one-dimensional or multi-dimensional data set. This range is split into a hierarchy of ND-Range, work-groups, sub-groups, and work-items as shown in Figure 2 for a three-dimensional case.

Relationship between ND-Range, work-groups, sub-groups and work-items

Note that this is similar to the SYCL model, with the exception of sub-groups, which are an Intel extension. The work-item is the smallest execution unit in the kernel. And the work-groups determine how data is shared among these work-items. These hierarchical layouts also determine the kind of memory that should be used to get better performance. For example, work-items typically operate on temporary data that’s stored in the device memory and work-groups use global memory. The sub-group classification was introduced to provide support for hardware resources that have a vector unit. This allows parallel execution on elements.

From Figure 2, it’s clear that the location of the work-group or work-item within ND-Range is important, since this determines the data point being updated within the computational kernel. The index into ND-Range that each work-item acts upon is determined using intrinsic functions in the nd_item class (global_id, work_group_id, sub_group_id, and local_id).

Memory Model

The oneAPI memory model defines the handling of memory objects by the host and device. It helps a user decide where memory will be allocated depending on the application’s needs. Memory objects are classified as type buffer or images. An accessor can be used to indicate the location of the memory object and the mode of access. The accessor provides different access targets for objects residing on the host, global memory on the device, the device’s local memory, or images residing on the host. The access types can be read, write, atomic, or read and write.

The Unified Shared Memory model allows the host and device to share memory without the use of explicit accessors. Synchronization using events manages the dependencies between host and device. A user can either explicitly specify an event to control when data updated by a host or device is available for reuse, or implicitly depend on the runtime and device drivers to determine this.

Kernel Programming Model

The oneAPI kernel programming model specifies the code that’s executed on the host and device. Parallelism isn't automatic. The user needs to specify it explicitly using language constructs.

The DPC++ language requires a compiler that can support C++11 and later features on the host side. The device code, however, requires a compiler that supports C++03 features and certain C++11 features like lambda expressions, variadic templates, rvalue references, and alias templates. It also requires std::string, std::vector, and std::function support. There are restrictions on certain features for the device code which include virtual functions and virtual inheritance, exception handling, run-time type information (RTTI), and object management employing new and delete operators.

The user can decide to use different schemes to describe the separation between the host and device code. A lambda expression can keep the kernel code in line with the host code. A functor keeps the host code in the same source file, but in a separate function. For users who are porting OpenCL code, or those who require an explicit interface between the host and device code, the kernel class provides the necessary interface.

The user can implement parallelism in three different ways:

- A single task that executes the whole kernel in a single work-item

- The parallel_for construct, which distributes the tasks among the processing elements

- The parallel_for_work_group. The

parallel_for_work_group construct distributes the tasks among the work-groups and can synchronize work-items within a work-group through the use of barriers.

oneAPI Compilation Model

The oneAPI compilation model consists of build and link steps. However, the binary generated needs to support the execution of the device code on multiple accelerators. This means a DPC++ compiler and linker have to carry out additional commands to generate the binary. This complexity is generally hidden from the user, but can be useful for generating target-specific binaries.

The host code compilation is done in the default way for a standard x86 architecture. The binary generation for the accelerator is more complex because it needs to support single or multiple accelerators in addition to optimizations that are specific to each accelerator. This accelerator binary, known as a fat binary, contains a combination of:

- An intermediate Standard Portable Intermediate Representation (SPIR-V) representation, which is device-independent and generates a device-specific binary during compilation.

- Target-specific binaries that are generated at compile-time. Since oneAPI is meant to support multiple accelerators, multiple code forms are created.

Multiple tools generate these code representations, including the clang driver, the host and device DPC++ compiler, the standard Linux* (ld) or Windows* (link.exe) linker, and tools to generate the fat object file. During execution, the oneAPI runtime environment checks for a device-specific image within the fat binary and executes it, if available. Otherwise, the SPIR-V image is used to generate the targetspecific image.

oneAPI Programming Examples

In this section, we look at sample code for the beta Intel oneAPI DPC++ Compiler, OpenMP device offload, and the Intel DPC++ Compatibility Tool.

Writing DPC++ Code

Writing DPC++ code requires a user to exploit the APIs and syntax of the language. Listing 1 shows some sample code conversion from C++ (CPU) code to a DPC++ (host and accelerator) code. It’s an implementation of the Högbom CLEAN* algorithm posted on GitHub4. The algorithm iteratively finds the highest value in the image and subtracts a small gain of this point source convolved with the point spread function of the observation until the highest value is smaller than some threshold. The implementation has two functions: findPeak and subtractPSF. These have to be ported from C++ to DPC++ as shown in Listings 1 and 2.

Listing 1. Baseline and DPC++ implementation of the subtractPSF code

Code changes required to port from C/C++ to DPC++ include:

- Introduction of the device queue for a given device (using the device selector API)

- Buffers created/accessed on the device (using the sycl::buffer/get_access APIs)

- Invocation of the parallel_for to spawn/execute the computational kernel

- Wait for the completion of the kernel execution (and optionally catch any exceptions)

- Intel® DPC++ Compiler and flags: dpcpp -std=c++11 -O2 -lsycl -lOpenCL

Listing 2 shows the code changes for the findPeak function implementation. To better exploit parallelism in the hardware, DPC++ code has support for local_work_size, global_id/local_id, workgroup, and many other APIs, similar to the constructs used in OpenCL and OpenMP.

Listing 2. Baseline (top) and DPC++ (bottom) implementation of the findPeak code. clPeak is a structure of value and position data. Concurrent execution of work-groups is accomplished using the global and local IDs, and barrier synchronization across multiple threads (work-items) in a workgroup. The result of this parallel_for execution is further reduced (not shown) to determine the maximum value and position across work-groups.

OpenMP Offload Support

The beta Intel oneAPI HPC Toolkit provides OpenMP offload support, which enables users to take advantage of OpenMP device offload features. We look at a sample open-source Jacobi code3 written in C++ with OpenMP pragmas. The code has a main iteration step that:

- Calculates the Jacobi update

- Calculates the difference between the old and new solution

- Updates the old solution

- Calculates the residual

The iteration code snippet is shown in Listing 3.

Listing 3. Sample Jacobi solver with OpenMP pragmas

Listing 4 shows the updated code with the omp target clause, which can be used to specify the data to be transferred to the device environment, along with a data modifier that can either be to, from, tofrom, or alloc. Since array b is not modified, we use the clause to. And since x and xnew are initialized before the offload directives and updated within the device environment, we use the tofrom clause. The reduction variables d and r are also set and updated during each iteration and have the tofrom map clause.

Listing 4. Sample Jacobi solver updated with OpenMP offload pragmas

To compile the offload target code with the oneAPI compiler, the user needs to set:

- The environment variables pertaining to the compiler path

- The relevant libraries

- The different components

The path to these environment variables will depend on the oneAPI setup on the user machine. We look at the compilation process for now, which will be similar across machines, to demonstrate the ease of use of the specification. To compile the code, use the LLVM-based icx or icpc -qnextgen compiler as follows:

$ export OMP_TARGET_OFFLOAD=”MANDATORY”

$ export LIBOMPTARGET_DEBUG=1

$./jacobi

The -D__STRICT__ANSI flag ensures compatibility with GCC 7.x and higher systems. The spir64 flag refers to the target independent representation of the code and is ported to target-specific code during the link stage or execution. To execute the code, run these commands:

The MANDATORY option for OMP_TARGET_OFFLOAD indicates that the offload has to be run on the GPU. It's set to DEFAULT by default, which indicates offload can be run on CPU and GPU. The LIBOMPTARGET_DEBUG flag, when set, provides offload runtime information that helps in debugging.

The OpenMP offload support example is for C/C++ programs, but Fortran offload is also supported. This allows HPC users with Fortran code bases to run their code on GPUs as well.

Intel DPC++ Compatibility Tool

The Intel DPC++ Compatibility Tool is a command-line-based code migration tool available as part of the Intel oneAPI Base Toolkit. Its primary role is to enable the porting of existing CUDA sources to DPC++. Source locations where automatic migration isn't possible are flagged through suitable errors and warnings. The Intel DPC++ Compatibility Tool also inserts comments in source locations where user interventions are necessary.

Figure 3 shows a typical workflow that CUDA users can use to port their source code to DPC++. The Intel DPC++ Compatibility Tool currently supports the Linux* and Windows* operating systems. This article assumes a Linux environment. The Intel DPC++ Compatibility Tool currently requires header files that are shipped with CUDA SDK. To demonstrate the migration process, we use the VectorAdd sample from CUDA SDK 10.1, typically found in a location similar to:

$ ls /usr/local/cuda-10.1/samples/0_Simple/vectorAdd

$ icpc -fiopenmp -fopenmp-targets=spir64 -D__STRICT_ANSI__ jacobi.cpp -o

jacobi

Recommended workflow for migrating existing CUDA applications

VectorAdd is a single-source example with around 150 lines of code. The CUDA kernel device code in this case computes the vector addition of arrays A and B into array C.

Note that the commands, paths, and procedure shown here are correct at the time of publishing. Some changes may be introduced in the final version of the product.

To initialize the environment to use the Intel DPC++ Compatibility Tool, run the following command:

$ source /opt/intel/inteloneapi/setvars.sh

The setvars.sh script not only initializes the environment for the Intel DPC++ Compatibility Tool, but all other tools available in the Intel oneAPI Base Toolkit.

A simplified version of the CUDA Makefile is used, as shown in Listing 5.

Listing 5. Makefile for porting CUDA code to DPC++

The next step intercepts commands issued as the Makefile executes and stores them in a compilation database file in JSON format. The Intel DPC++ Compatibility Tool provides a utility called intercept-build for this purpose. Here's a sample invocation:

$ intercept-build make

The real conversion step is then invoked:

$ dpct -p compile_commands.json --in-root=. --out-root=dpct_output

vectorAdd.cu

The --in-root and --out-root flags set the location of user program source and location where the migrated DPC++ code must be written. This step generates ./dpct_output/vectorAdd.dp.cpp.

To ensure that vector addition is deployed onto the integrated GPU, explicit specification of the GPU queue is made instead of the submission to the default queue. The list of supported platforms is obtained with the list of devices for each platform by calling get_platforms() and platform.get_devices(). With the target device identified, a queue is constructed for the integrated GPU and the vector add kernel is dispatched to this queue. Such a methodology may be used to target multiple independent kernels to different target devices connected to the same host/node.

Next, the modified DPC++ code is compiled using:

$ dpcpp -std=c++11 -I=/usr/local/cuda-10.1/samples/common/inc

vectorAdd.dp.cpp -lOpenCL

The resulting binary is then invoked, and the vector addition is confirmed to be executing on the integrated GPU, shown in Listing 6.

Listing 6. Output from running the ported DPC++ code on the integrated GPU

For details on these tools, use these help flags:

$ intercept-build –h

$ dpct –h

Uncompromised Performance for Diverse Workloads Across Multiple Architectures

This article introduced oneAPI and the beta Intel oneAPI Toolkits and outlined the components that are part of the Intel oneAPI Base Toolkit. The beta release includes toolkits to help users in the HPC, AI, analytics, deep learning, IoT, and video analytics domains transition to oneAPI. The DPC++ programming guide provides complete details on the various constructs supported for optimized accelerator performance. The OpenMP example shown in the article is for a C++ program. However, GPU offload will be supported for C and Fortran as well. oneAPI provides the software ecosystem you need to port and run your code on multiple accelerators.

References

- Intel® VTune™ Profiler

- Intel® Advisor

- Jacobi solver using OpenMP

- https://github.com/ATNF/askap-benchmarks/tree/master/tHogbomCleanOMP