When you build an application with JavaScript, you always want to modularize your code. However, JavaScript language was initially invented for simple form manipulation, with no built-in features like module or namespace. In years, tons of technologies are invented to modularize JavaScript. This article discusses all mainstream terms, patterns, libraries, syntax, and tools for JavaScript modules.

Table of Contents

- IIFE module: JavaScript module pattern

- Revealing module: JavaScript revealing module pattern

- CJS module: CommonJS module, or Node.js module

- AMD module: Asynchronous Module Definition, or RequireJS module

- UMD module: Universal Module Definition, or UmdJS module

- ES module: ECMAScript 2015, or ES6 module

- ES dynamic module: ECMAScript 2020, or ES11 dynamic module

- System module: SystemJS module

- Webpack module: bundle from CJS, AMD, ES modules

- Babel module: transpile from ES module

- TypeScript module: Transpile to CJS, AMD, ES, System modules

- Conclusion

- History

In the browser, defining a JavaScript variable is defining a global variable, which causes pollution across all JavaScript files loaded by the current web page:

let count = 0;

const increase = () => ++count;

const reset = () => {

count = 0;

console.log("Count is reset.");

};

increase();

reset();

To avoid global pollution, an anonymous function can be used to wrap the code:

(() => {

let count = 0;

});

Apparently, there is no longer any global variable. However, defining a function does not execute the code inside the function.

To execute the code inside a function f, the syntax is function call () as f(). To execute the code inside an anonymous function (() => {}), the same function call syntax () can be used as (() => {})():

(() => {

let count = 0;

})();

This is called an IIFE (Immediately invoked function expression). So a basic module can be defined in this way:

const iifeCounterModule = (() => {

let count = 0;

return {

increase: () => ++count,

reset: () => {

count = 0;

console.log("Count is reset.");

}

};

})();

iifeCounterModule.increase();

iifeCounterModule.reset();

It wraps the module code inside an IIFE. The anonymous function returns an object, which is the placeholder of exported APIs. Only 1 global variable is introduced, which is the module name (or namespace). Later, the module name can be used to call the exported module APIs. This is called the module pattern of JavaScript.

When defining a module, some dependencies may be required. With IIFE module pattern, each dependent module is a global variable. The dependent modules can be directly accessed inside the anonymous function, or they can be passed as the anonymous function’s arguments:

const iifeCounterModule = ((dependencyModule1, dependencyModule2) => {

let count = 0;

return {

increase: () => ++count,

reset: () => {

count = 0;

console.log("Count is reset.");

}

};

})(dependencyModule1, dependencyModule2);

The early version of popular libraries, like jQuery, followed this pattern. (The latest version of jQuery follows the UMD module, which is explained later in this article.)

The revealing module pattern is named by Christian Heilmann. This pattern is also an IIFE, but it emphasizes defining all APIs as local variables inside the anonymous function:

const revealingCounterModule = (() => {

let count = 0;

const increase = () => ++count;

const reset = () => {

count = 0;

console.log("Count is reset.");

};

return {

increase,

reset

};

})();

revealingCounterModule.increase();

revealingCounterModule.reset();

With this syntax, it becomes easier when the APIs need to call each other.

CommonJS, initially named ServerJS, is a pattern to define and consume modules. It is implemented by Node,js. By default, each .js file is a CommonJS module. A module variable and an exports variable are provided for a module (a file) to expose APIs. And a require function is provided to load and consume a module. The following code defines the counter module in CommonJS syntax:

const dependencyModule1 = require("./dependencyModule1");

const dependencyModule2 = require("./dependencyModule2");

let count = 0;

const increase = () => ++count;

const reset = () => {

count = 0;

console.log("Count is reset.");

};

exports.increase = increase;

exports.reset = reset;

module.exports = {

increase,

reset

};

The following example consumes the counter module:

const { increase, reset } = require("./commonJSCounterModule");

increase();

reset();

const commonJSCounterModule = require("./commonJSCounterModule");

commonJSCounterModule.increase();

commonJSCounterModule.reset();

At runtime, Node.js implements this by wrapping the code inside the file into a function, then passes the exports variable, module variable, and require function through arguments.

(function (exports, require, module, __filename, __dirname) {

const dependencyModule1 = require("./dependencyModule1");

const dependencyModule2 = require("./dependencyModule2");

let count = 0;

const increase = () => ++count;

const reset = () => {

count = 0;

console.log("Count is reset.");

};

module.exports = {

increase,

reset

};

return module.exports;

}).call(thisValue, exports, require, module, filename, dirname);

(function (exports, require, module, __filename, __dirname) {

const commonJSCounterModule = require("./commonJSCounterModule");

commonJSCounterModule.increase();

commonJSCounterModule.reset();

}).call(thisValue, exports, require, module, filename, dirname);

AMD (Asynchronous Module Definition), is a pattern to define and consume module. It is implemented by RequireJS library. AMD provides a define function to define module, which accepts the module name, dependent modules’ names, and a factory function:

define("amdCounterModule", ["dependencyModule1", "dependencyModule2"],

(dependencyModule1, dependencyModule2) => {

let count = 0;

const increase = () => ++count;

const reset = () => {

count = 0;

console.log("Count is reset.");

};

return {

increase,

reset

};

});

It also provides a require function to consume module:

require(["amdCounterModule"], amdCounterModule => {

amdCounterModule.increase();

amdCounterModule.reset();

});

The AMD require function is totally different from the CommonJS require function. AMD require accepts the names of modules to be consumed, and passes the module to a function argument.

AMD’s define function has another overload. It accepts a callback function, and passes a CommonJS-like require function to that callback. Inside the callback function, require can be called to dynamically load the module:

define(require => {

const dynamicDependencyModule1 = require("dependencyModule1");

const dynamicDependencyModule2 = require("dependencyModule2");

let count = 0;

const increase = () => ++count;

const reset = () => {

count = 0;

console.log("Count is reset.");

};

return {

increase,

reset

};

});

The above define function overload can also pass the require function as well as exports variable and module to its callback function. So inside the callback, CommonJS syntax code can work:

define((require, exports, module) => {

const dependencyModule1 = require("dependencyModule1");

const dependencyModule2 = require("dependencyModule2");

let count = 0;

const increase = () => ++count;

const reset = () => {

count = 0;

console.log("Count is reset.");

};

exports.increase = increase;

exports.reset = reset;

});

define(require => {

const counterModule = require("amdCounterModule");

counterModule.increase();

counterModule.reset();

});

UMD (Universal Module Definition) is a set of tricky patterns to make your code file work in multiple environments.

For example, the following is a kind of UMD pattern to make module definition work with both AMD (RequireJS) and native browser:

((root, factory) => {

if (typeof define === "function" && define.amd) {

define("umdCounterModule", ["deependencyModule1", "dependencyModule2"], factory);

} else {

root.umdCounterModule = factory(root.deependencyModule1, root.dependencyModule2);

}

})(typeof self !== "undefined" ? self : this, (deependencyModule1, dependencyModule2) => {

let count = 0;

const increase = () => ++count;

const reset = () => {

count = 0;

console.log("Count is reset.");

};

return {

increase,

reset

};

});

It is more complex but it is just an IIFE. The anonymous function detects if AMD’s define function exists.

- If yes, call the module factory with AMD’s

define function. - If not, it calls the module factory directly. At this moment, the

root argument is actually the browser’s window object. It gets dependency modules from global variables (properties of window object). When factory returns the module, the returned module is also assigned to a global variable (property of window object).

The following is another kind of UMD pattern to make module definition work with both AMD (RequireJS) and CommonJS (Node.js):

(define => define((require, exports, module) => {

const dependencyModule1 = require("dependencyModule1");

const dependencyModule2 = require("dependencyModule2");

let count = 0;

const increase = () => ++count;

const reset = () => {

count = 0;

console.log("Count is reset.");

};

module.export = {

increase,

reset

};

}))(

typeof module === "object" && module.exports && typeof define !== "function"

?

factory => module.exports = factory(require, exports, module)

:

define);

Again, don’t be scared. It is just another IIFE. When the anonymous function is called, its argument is evaluated. The argument evaluation detects the environment (check the module variable and exports variable of CommonJS/Node.js, as well as the define function of AMD/RequireJS).

- If the environment is CommonJS/Node.js, the anonymous function’s argument is a manually created

define function. - If the environment is AMD/RequireJS, the anonymous function’s argument is just AMD’s

define function. So when the anonymous function is executed, it is guaranteed to have a working define function. Inside the anonymous function, it simply calls the define function to create the module.

After all the module mess, in 2015, JavaScript’s spec version 6 introduces one more different module syntax. This spec is called ECMAScript 2015 (ES2015), or ECMAScript 6 (ES6). The main syntax is the import keyword and the export keyword. The following example uses new syntax to demonstrate ES module’s named import/export and default import/export:

import dependencyModule1 from "./dependencyModule1.mjs";

import dependencyModule2 from "./dependencyModule2.mjs";

let count = 0;

export const increase = () => ++count;

export const reset = () => {

count = 0;

console.log("Count is reset.");

};

export default {

increase,

reset

};

To use this module file in browser, add a <script> tag and specify it is a module: <script type="module" src="esCounterModule.js"></script>. To use this module file in Node.js, rename its extension from .js to .mjs.

import { increase, reset } from "./esCounterModule.mjs";

increase();

reset();

import esCounterModule from "./esCounterModule.mjs";

esCounterModule.increase();

esCounterModule.reset();

For browser, <script>’s nomodule attribute can be used for fallback:

<script nomodule>

alert("Not supported.");

</script>

In 2020, the latest JavaScript spec version 11 is introducing a built-in function import to consume an ES module dynamically. The import function returns a promise, so its then method can be called to consume the module:

import("./esCounterModule.js").then(({ increase, reset }) => {

increase();

reset();

});

import("./esCounterModule.js").then(dynamicESCounterModule => {

dynamicESCounterModule.increase();

dynamicESCounterModule.reset();

});

By returning a promise, apparently, import function can also work with the await keyword:

(async () => {

const { increase, reset } = await import("./esCounterModule.js");

increase();

reset();

const dynamicESCounterModule = await import("./esCounterModule.js");

dynamicESCounterModule.increase();

dynamicESCounterModule.reset();

})();

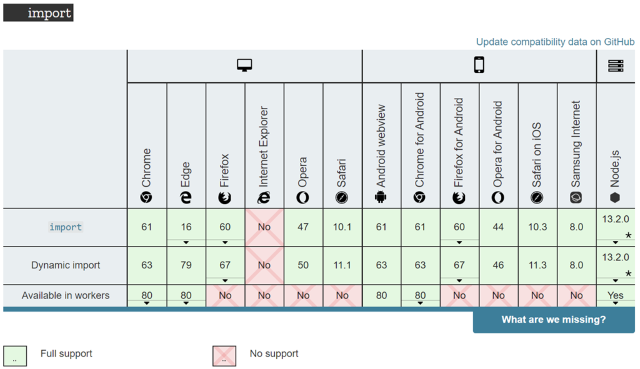

The following is the compatibility of import/dynamic import/export, from this link:

SystemJS is a library that can enable ES module syntax for older ES. For example, the following module is defined in ES 6syntax:

import dependencyModule1 from "./dependencyModule1.js";

import dependencyModule2 from "./dependencyModule2.js";

dependencyModule1.api1();

dependencyModule2.api2();

let count = 0;

export const increase = function () { return ++count };

export const reset = function () {

count = 0;

console.log("Count is reset.");

};

export default {

increase,

reset

}

If the current runtime, like an old browser, does not support ES6 syntax, the above code cannot work. One solution is to transpile the above module definition to a call of SystemJS library API, System.register:

System.register(["./dependencyModule1.js", "./dependencyModule2.js"],

function (exports_1, context_1) {

"use strict";

var dependencyModule1_js_1, dependencyModule2_js_1, count, increase, reset;

var __moduleName = context_1 && context_1.id;

return {

setters: [

function (dependencyModule1_js_1_1) {

dependencyModule1_js_1 = dependencyModule1_js_1_1;

},

function (dependencyModule2_js_1_1) {

dependencyModule2_js_1 = dependencyModule2_js_1_1;

}

],

execute: function () {

dependencyModule1_js_1.default.api1();

dependencyModule2_js_1.default.api2();

count = 0;

exports_1("increase", increase = function () { return ++count };

exports_1("reset", reset = function () {

count = 0;

console.log("Count is reset.");

};);

exports_1("default", {

increase,

reset

});

}

};

});

So that the import/export new ES6 syntax is gone. The old API call syntax works for sure. This transpilation can be done automatically with Webpack, TypeScript, etc., which are explained later in this article.

SystemJS also provides an import function for dynamic import:

System.import("./esCounterModule.js").then(dynamicESCounterModule => {

dynamicESCounterModule.increase();

dynamicESCounterModule.reset();

});

Webpack is a bundler for modules. It transpiles combined CommonJS module, AMD module, and ES module into a single harmony module pattern, and bundle all code into a single file. For example, the following three files define three modules in three different syntaxes:

define("amdDependencyModule1", () => {

const api1 = () => { };

return {

api1

};

});

const dependencyModule1 = require("./amdDependencyModule1");

const api2 = () => dependencyModule1.api1();

exports.api2 = api2;

import dependencyModule1 from "./amdDependencyModule1";

import dependencyModule2 from "./commonJSDependencyModule2";

dependencyModule1.api1();

dependencyModule2.api2();

let count = 0;

const increase = () => ++count;

const reset = () => {

count = 0;

console.log("Count is reset.");

};

export default {

increase,

reset

}

And the following file consumes the counter module:

import counterModule from "./esCounterModule";

counterModule.increase();

counterModule.reset();

Webpack can bundle all the above files, even they are in 3 different module systems, into a single file main.js:

- root

- dist

- main.js (Bundle of all files under src)

- src

- amdDependencyModule1.js

- commonJSDependencyModule2.js

- esCounterModule.js

- index.js

- webpack.config.js

Since Webpack is based on Node.js, Webpack uses CommonJS module syntax for itself. In webpack.config.js:

const path = require('path');

module.exports = {

entry: './src/index.js',

mode: "none",

output: {

filename: 'main.js',

path: path.resolve(__dirname, 'dist'),

},

};

Now run the following command to transpile and bundle all four files, which are in different syntax:

npm install webpack webpack-cli --save-dev

npx webpack --config webpack.config.js

AS a result, Webpack generates the bundle file main.js. The following code in main.js is reformatted, and variables are renamed, to improve readability:

(function (modules) {

var installedModules = {};

function require(moduleId) {

if (installedModules[moduleId]) {

return installedModules[moduleId].exports;

}

var module = installedModules[moduleId] = {

i: moduleId,

l: false,

exports: {}

};

modules[moduleId].call(module.exports, module, module.exports, require);

module.l = true;

return module.exports;

}

require.m = modules;

require.c = installedModules;

require.d = function (exports, name, getter) {

if (!require.o(exports, name)) {

Object.defineProperty(exports, name, { enumerable: true, get: getter });

}

};

require.r = function (exports) {

if (typeof Symbol !== 'undefined' && Symbol.toStringTag) {

Object.defineProperty(exports, Symbol.toStringTag, { value: 'Module' });

}

Object.defineProperty(exports, '__esModule', { value: true });

};

require.t = function (value, mode) {

if (mode & 1) value = require(value);

if (mode & 8) return value;

if ((mode & 4) && typeof value === 'object' && value && value.__esModule)

return value;

var ns = Object.create(null);

require.r(ns);

Object.defineProperty(ns, 'default', { enumerable: true, value: value });

if (mode & 2 && typeof value != 'string') for (var key in value)

require.d(ns, key, function (key) { return value[key]; }.bind(null, key));

return ns;

};

require.n = function (module) {

var getter = module && module.__esModule ?

function getDefault() { return module['default']; } :

function getModuleExports() { return module; };

require.d(getter, 'a', getter);

return getter;

};

require.o = function (object, property)

{ return Object.prototype.hasOwnProperty.call(object, property); };

require.p = "";

return require(require.s = 0);

})([

function (module, exports, require) {

"use strict";

require.r(exports);

var esCounterModule = require(1);

esCounterModule["default"].increase();

esCounterModule["default"].reset();

},

function (module, exports, require) {

"use strict";

require.r(exports);

var amdDependencyModule1 = require.n(require(2));

var commonJSDependencyModule2 = require.n(require(3));

amdDependencyModule1.a.api1();

commonJSDependencyModule2.a.api2();

let count = 0;

const increase = () => ++count;

const reset = () => {

count = 0;

console.log("Count is reset.");

};

exports["default"] = {

increase,

reset

};

},

function (module, exports, require) {

var result;

!(result = (() => {

const api1 = () => { };

return {

api1

};

}).call(exports, require, exports, module),

result !== undefined && (module.exports = result));

},

function (module, exports, require) {

const dependencyModule1 = require(2);

const api2 = () => dependencyModule1.api1();

exports.api2 = api2;

}

]);

Again, it is just another IIFE. The code of all four files is transpiled to the code in four functions in an array. And that array is passed to the anonymous function as an argument.

Babel is another transpiler to convert ES6+ JavaScript code to the older syntax for the older environment like older browsers. The above counter module in ES6 import/export syntax can be converted to the following babel module with new syntax replaced:

Object.defineProperty(exports, "__esModule", {

value: true

});

exports["default"] = void 0;

function _interopRequireDefault(obj)

{ return obj && obj.__esModule ? obj : { "default": obj }; }

var dependencyModule1 = _interopRequireDefault(require("./amdDependencyModule1"));

var dependencyModule2 = _interopRequireDefault(require("./commonJSDependencyModule2"));

dependencyModule1["default"].api1();

dependencyModule2["default"].api2();

var count = 0;

var increase = function () { return ++count; };

var reset = function () {

count = 0;

console.log("Count is reset.");

};

exports["default"] = {

increase: increase,

reset: reset

};

And here is the code in index.js which consumes the counter module:

function _interopRequireDefault(obj)

{ return obj && obj.__esModule ? obj : { "default": obj }; }

var esCounterModule = _interopRequireDefault(require("./esCounterModule.js"));

esCounterModule["default"].increase();

esCounterModule["default"].reset();

This is the default transpilation. Babel can also work with other tools.

SystemJS can be used as a plugin for Babel:

npm install --save-dev @babel/plugin-transform-modules-systemjs

And it should be added to the Babel configuration babel.config.json:

{

"plugins": ["@babel/plugin-transform-modules-systemjs"],

"presets": [

[

"@babel/env",

{

"targets": {

"ie": "11"

}

}

]

]

}

Now Babel can work with SystemJS to transpile CommonJS/Node.js module, AMD/RequireJS module, and ES module:

npx babel src --out-dir lib

The result is:

- root

- lib

- amdDependencyModule1.js (Transpiled with SystemJS)

- commonJSDependencyModule2.js (Transpiled with SystemJS)

- esCounterModule.js (Transpiled with SystemJS)

- index.js (Transpiled with SystemJS)

- src

- amdDependencyModule1.js

- commonJSDependencyModule2.js

- esCounterModule.js

- index.js

- babel.config.json

Now all the ADM, CommonJS, and ES module syntax are transpiled to SystemJS syntax:

System.register([], function (_export, _context) {

"use strict";

return {

setters: [],

execute: function () {

define("amdDependencyModule1", () => {

const api1 = () => { };

return {

api1

};

});

}

};

});

System.register([], function (_export, _context) {

"use strict";

var dependencyModule1, api2;

return {

setters: [],

execute: function () {

dependencyModule1 = require("./amdDependencyModule1");

api2 = () => dependencyModule1.api1();

exports.api2 = api2;

}

};

});

System.register(["./amdDependencyModule1", "./commonJSDependencyModule2"],

function (_export, _context) {

"use strict";

var dependencyModule1, dependencyModule2, count, increase, reset;

return {

setters: [function (_amdDependencyModule) {

dependencyModule1 = _amdDependencyModule.default;

}, function (_commonJSDependencyModule) {

dependencyModule2 = _commonJSDependencyModule.default;

}],

execute: function () {

dependencyModule1.api1();

dependencyModule2.api2();

count = 0;

increase = () => ++count;

reset = () => {

count = 0;

console.log("Count is reset.");

};

_export("default", {

increase,

reset

});

}

};

});

System.register(["./esCounterModule"], function (_export, _context) {

"use strict";

var esCounterModule;

return {

setters: [function (_esCounterModuleJs) {

esCounterModule = _esCounterModuleJs.default;

}],

execute: function () {

esCounterModule.increase();

esCounterModule.reset();

}

};

});

TypeScript supports all JavaScript syntax, including the ES6 module syntax. When TypeScript transpiles, the ES module code can either be kept as ES6, or transpiled to other formats, including CommonJS/Node.js, AMD/RequireJS, UMD/UmdJS, or System/SystemJS, according to the specified transpiler options in tsconfig.json:

{

"compilerOptions": {

"module": "ES2020",

}

}

For example:

import dependencyModule from "./dependencyModule";

dependencyModule.api();

let count = 0;

export const increase = function () { return ++count };

var __importDefault = (this && this.__importDefault) || function (mod) {

return (mod && mod.__esModule) ? mod : { "default": mod };

};

exports.__esModule = true;

var dependencyModule_1 = __importDefault(require("./dependencyModule"));

dependencyModule_1["default"].api();

var count = 0;

exports.increase = function () { return ++count; };

var __importDefault = (this && this.__importDefault) || function (mod) {

return (mod && mod.__esModule) ? mod : { "default": mod };

};

define(["require", "exports", "./dependencyModule"],

function (require, exports, dependencyModule_1) {

"use strict";

exports.__esModule = true;

dependencyModule_1 = __importDefault(dependencyModule_1);

dependencyModule_1["default"].api();

var count = 0;

exports.increase = function () { return ++count; };

});

var __importDefault = (this && this.__importDefault) || function (mod) {

return (mod && mod.__esModule) ? mod : { "default": mod };

};

(function (factory) {

if (typeof module === "object" && typeof module.exports === "object") {

var v = factory(require, exports);

if (v !== undefined) module.exports = v;

}

else if (typeof define === "function" && define.amd) {

define(["require", "exports", "./dependencyModule"], factory);

}

})(function (require, exports) {

"use strict";

exports.__esModule = true;

var dependencyModule_1 = __importDefault(require("./dependencyModule"));

dependencyModule_1["default"].api();

var count = 0;

exports.increase = function () { return ++count; };

});

System.register(["./dependencyModule"], function (exports_1, context_1) {

"use strict";

var dependencyModule_1, count, increase;

var __moduleName = context_1 && context_1.id;

return {

setters: [

function (dependencyModule_1_1) {

dependencyModule_1 = dependencyModule_1_1;

}

],

execute: function () {

dependencyModule_1["default"].api();

count = 0;

exports_1("increase", increase = function () { return ++count; });

}

};

});

The ES module syntax supported in TypeScript was called external modules.

TypeScript also has a module keyword and a namespace keyword https://www.typescriptlang.org/docs/handbook/namespaces-and-modules.html#pitfalls-of-namespaces-and-modules. They were called internal modules:

module Counter {

let count = 0;

export const increase = () => ++count;

export const reset = () => {

count = 0;

console.log("Count is reset.");

};

}

namespace Counter {

let count = 0;

export const increase = () => ++count;

export const reset = () => {

count = 0;

console.log("Count is reset.");

};

}

They are both transpiled to JavaScript objects:

var Counter;

(function (Counter) {

var count = 0;

Counter.increase = function () { return ++count; };

Counter.reset = function () {

count = 0;

console.log("Count is reset.");

};

})(Counter || (Counter = {}));

TypeScript module and namespace can have multiple levels by supporting the . separator:

module Counter.Sub {

let count = 0;

export const increase = () => ++count;

}

namespace Counter.Sub {

let count = 0;

export const increase = () => ++count;

}

The sub module and sub namespace are both transpiled to object’s property:

var Counter;

(function (Counter) {

var Sub;

(function (Sub) {

var count = 0;

Sub.increase = function () { return ++count; };

})(Sub = Counter.Sub || (Counter.Sub = {}));

})(Counter|| (Counter = {}));

TypeScript module and namespace can also be used in the export statement:

module Counter {

let count = 0;

export module Sub {

export const increase = () => ++count;

}

}

module Counter {

let count = 0;

export namespace Sub {

export const increase = () => ++count;

}

}

The transpilation is the same as submodule and sub-namespace:

var Counter;

(function (Counter) {

var count = 0;

var Sub;

(function (Sub) {

Sub.increase = function () { return ++count; };

})(Sub = Counter.Sub || (Counter.Sub = {}));

})(Counter || (Counter = {}));

Welcome to JavaScript, which has so much drama - 10+ systems/formats just for modularization/namespace:

- IIFE module: JavaScript module pattern

- Revealing module: JavaScript revealing module pattern

- CJS module: CommonJS module, or Node.js module

- AMD module: Asynchronous Module Definition, or RequireJS module

- UMD module: Universal Module Definition, or UmdJS module

- ES module: ECMAScript 2015, or ES6 module

- ES dynamic module: ECMAScript 2020, or ES11 dynamic module

- System module: SystemJS module

- Webpack module: transpile and bundle of CJS, AMD, ES modules

- Babel module: transpile ES module

- TypeScript module and namespace

Fortunately, now JavaScript has standard built-in language features for modules, and it is supported by Node.js and all the latest modern browsers. For the older environments, you can still code with the new ES module syntax, then use Webpack/Babel/SystemJS/TypeScript to transpile to older or compatible syntax.

- 16th April, 2020: Initial version