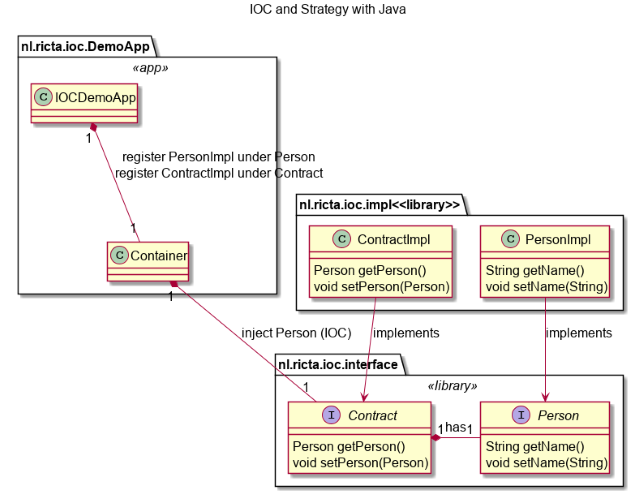

Inversion Of Control is a very powerful pattern as part and/or on top of the strategy pattern for loose coupling. Not only do you separate implementation from the interface (Strategy pattern), but you also invert the control of what the implementation should be. The control is no longer part of the using object, but control of implementation is inverted to an extern system (mostly, object containers, initialized by a using program). The container injects the implementation dependencies into all using objects that need an implementation for their required interfaces.

Using IOC (Dependency Injection) and Strategy pattern to loosely couple your implementation objects in your sub-systems ((micro)-services).

Introduction

This article provides the concept and implementation of Inversion Of Control, aka IOC through Dependency Injection (DI).

It is used in combination with the Strategy pattern with interfaces and implementation classes. After that, examples follow in Java (using Spring Boot) and .NET C# (using Autofac).

As explained in short, IOC (DI) on top of the Strategy pattern allows OO classes to be very loosely coupled inside the implementation of a component. That allows for much easier refactoring of code, better re-use of classes, and (if properly designed), better separation of concern, and easier to adjust components to new or changed functionality (flexibility and ease of adoption to changes). So, although it is not a pattern to loosely couple components together, it certainly can help in re-using (e.g., binary) libraries created with these patterns in other components or apps.

See related articles:

How is this article built up?

- Examples in Java and C# of final usage of Strategy and IOC (through Dependency Injection)

- Concept of Strategy pattern

- Concepts of IOC with DI (IOC, Field and CTOR injection)

- Java implementation details Spring Boot

- C# implementation details with AutoFac

- Wrap-up and conclusions, and more

Before Reading This Article

I will show the Strategy pattern in Java and C#. IOC(Dependency Injection) on top of Strategy in Java is demonstrated with the Spring Boot ApplicationContext container and @Autowiring.

IOC(Dependency Injection) on top of Strategy in C# is demonstrated using Autofac.

Note: The purist under us of course will say, "DI is not the same IOC", it is "an implementation" of IOC. Duly noted. See also [2].

Strategy Pattern Final Usage Example in Java (1+)

Contract contract = new ContractImpl("cloe");

Contract contract = new ContractImpl();

contract.getPerson().setName("roland");

Strategy Pattern Final Usage Example in C# (4+)

IContract contract = new Contract("cloe");

IContract contract = new Contract();

contract.Person().Name = "roland";

IOC Pattern Final Usage Example in Java (1+)

@Autowired

public Contract contract;

public void run(String... args) {

contract.getPerson().setName("roland");

}

IOC Pattern Final Usage Example in C# (4+)

IContract contract = container.Resolve<IContract>();

contract.Person().Name = "roland";

Concept of Strategy Pattern

The idea of this pattern is a basic OO idea: separate class implementation from its interface. So, all "public" behaviour is exposed through the interface of the class.

In this article, I choose for the "clean" implementation, and separated the interfaces from the classes in separate libraries.

I always do advice this kind of implementation. This is not in the scope of this article to go into detail on this aspect. But trust me, it is a little overhead, but in bigger systems, you will end up in complex build dependencies if you don't.

Interfaces, Interfaces, Interfaces...

In the basics, there are these steps:

- Define your

public methods in an interface - Implement the interface in a class

- Define your associations and/or aggregations on interface level instead of on an implementation level

Pros of Strategy Pattern

There are a real large number of important pros on Strategy, especially, in bigger systems:

- Build dependencies are much easier to solve: First build the component with all the interfaces, then the implementing components

- Testability in Unit tests is much easier. You can mock your interfaces more easily then your implementations

- Separation of interface and implementation allows for multiple implementations

- Dependency injection is much easier to implement

- If you do, Aspect-oriented programming and Interceptors using Proxies (See [3]) is possible. If you don't, it isn't.

Cons of Strategy Pattern

- You need to define your

public methods and properties twice (one in class, one in interface) which makes refactoring a bit more work - You may find code harder to read. After all, what is the implementation going to be behind the interface?

Note: There is almost no difference in Java and C# in the code implementing the Strategy pattern. Conceptually, 100% the same. The small differences are:

- C# has as coding standard default interface I... (

IContract, Contract) - Java has as coding standard default class ...Impl (

Contract, ContractImpl) - C# has

{get;set;} syntax (String Name {get;set;}) - Java has

Type get...() and set..(Type value) syntax (String getName() void setName(String name)).

Strategy Pattern Implementation in Java (1+)

public interface Person {

String getName();

void setName(String name);

}

public class PersonImpl implements Person {

private String name;

public String getName(){

return name;

}

public void setName(String name){

this.name = name;

}

}

public interface Contract {

Person getPerson();

void setPerson(Person person);

}

public class ContractImpl implements Contract{

private Person person = new PersonImpl();

public ContractImpl(){

}

public ContractImpl(String personName){

this.person.setName(personName);

}

public Person getPerson(){

return person;

}

public void setPerson(Person person){

this.person = person;

}

}

...

Contract contract = new ContractImpl("cloe");

Contract contract = new ContractImpl();

contract.getPerson().setName("roland");

Strategy Pattern Implementation Example in C# (1+)

public interface IPerson

{

String Name {get; set;}

}

public class Person : IPerson

{

public String Name {get; set;}

}

public interface IContract

{

IPerson Person {get; set;}

}

public class Contract : IContract

{

public Contract(){}

public Contract(String personName)

{

this.person.Name = personName;

}

public IPerson Person {get; set;} = new Person();

}

...

...

IContract contract = new Contract("cloe");

IContract contract = new Contract();

contract.Person.Name = "roland";

IOC Pattern Example in Java (1.7+, Spring Boot)

Now, only the implementations change, not the interfaces:

@Component

public class PersonImpl implements Person {

private String name;

public String getName(){

return name;

}

public void setName(String name){

this.name = name;

}

}

@Component

public class ContractImpl extends Contract{

@Autowired

private Person person;

public Person getPerson(){

return person;

}

}

...

@ComponentScan()

@SpringBootApplication()

public class IOCApplication {..}

...

public void run(String... args) {

Contract contract = context.getBean(Contract.class);

contract.getPerson().setName("roland");

}

...

@Autowired

public Contract contract;

public void run(String... args) {

contract.getPerson().setName("roland");

}

IOC Pattern Example in C# (C# 7+, Autofac)

Now, the code in C# has to change on one small point, and we have to do some object registration.

Note 1: This is an example of auto Field injection, supported by Autofac by ContainerBuilder.PropertiesAutowired();

Note 2: In the download code, there are two implementations, one for strategy, and one for IOC DI, and also a testproject for each.

public IPerson Person { get; set; }

ContainerBuilder containerBuilder = new ContainerBuilder();

containerBuilder

.RegisterType<Contract>()

.As<IContract>()

.PropertiesAutowired();

containerBuilder

.RegisterType<Person>()

.As<IPerson>()

.PropertiesAutowired();

IContainer container = containerBuilder.Build();

using (var scope = container.BeginLifetimeScope())

{

IContract contract = scope.Resolve<IContract>();

Assert.IsNotNull(contract.Person);

contract.Person.Name = "cloe";

Assert.AreEqual("cloe", contract.Person.Name);

}

Now, whereas Autofield injection is OK with me, because I'm a pragmatic guy, there are purists that favour Constructor injection. And, there are indeed situations where we need that or it makes the world a little cleaner. I advice to use CTOR injection always, but choose your pick and learn to live with it.

Pros are:

- CTOR DI code directly reveals all dependencies

- CTOR DI can by used to do extra initialization

Fine with me, here it is:

...

public Contract(IPerson person)

{

this.Person = person;

}

public Contract(IPerson person, String name)

{

this.Person = person;

person.Name = name;

}

...

ContainerBuilder containerBuilder = new ContainerBuilder();

containerBuilder

.RegisterType<Contract>()

.As<IContract>();

containerBuilder

.RegisterType<Person>()

.As<IPerson>();

...rest code same...

List<Parameter> parameters = new List<Parameter>();

parameters.Add(new NamedParameter("name", "cloe"));

contract = scope.Resolve<IContract>(parameters);

That concludes Strategy and IOC DI with Autofac in C#, with both Field and CTOR injection.

Note 1: Autofac has registration Module concepts. Please use them. See code attached in my other articles [3] and [4]

Conclusion

What Did We Learn in this Article?

- Strategy pattern is possible in C# and Java, almost 100% same.

- IOC DI is possible in C# and Java, both with CTOR and Field injection.

- We saw that it is now quite simple to add two implementations with the same interfaces (see attached code).

Points of Interest

Modern applications, whether or not apps, micro-services or libraries, almost all use containers and IOC. I did not go into lengthy features and concepts of containers, like Scope and LifeTime, and a zillion other features. There are examples enough on the Internet. As well as other containers than autofac (Pico, Castle Windsor, ...), I also did not go into detail on testing pros of the Strategy pattern, but I hope to write an article on layered unit testing as well, showing that.

A word of advice on structuring your code properly with a few tips:

If you find that you have more than 2 or 3 dependencies in your CTOR, you probably need to refactor your code. There is a big chance that your class has more than 1 responsibility. Split your class then, and let the caller use two classes that work together. Another solution is to use a Facade pattern, where you factor code to an extra class, with a subset of the dependencies, and include that class in your CTOR. You build some hierarchical "pipeline" then. That is fine. Either way: keep your dependencies [2-4] per class or so max.

I do want to note that I guess I started making code with IOC DI containers about 7 years ago. It changed my coding world completely. And, it takes a while (2 months or so) to get used to it. But, since I switched, I dare say, I can write real OO-code now. Not that I do it all the time :-), but I can now... What I did before was nothing of the kind, actually.

Then, a word on writing big systems or components with IOC and DI. I find IOC DI code quite easy to read per class, but very hard to follow the code throughout a component. Almost, impossible. And, that is good news!. Because the solution is simple: Document your components with UML class diagrams and sequence diagrams and the lot! UML gives all the possibilities to reveal that structure and flow of code. Use the power please?

And, if you hate UML drawing tools (I do), another tip: Start using PlantUML! See the UML code of this article attached as well. Don't let it be an excuse for not writing UML of your code. That is just plain unprofessional or lazy or both.

History

- 19th April, 2020: Initial version