In my case, “existing multi-node data-intensive application” translates to cassandra. In this post, you will see an overview of my solution and how I got to it.

The title screams many things. One of those things is Cassandra:

cassandra

noun

a daughter of the Trojan king Priam, who was given the gift of prophecy by Apollo.

When she cheated him, however, he turned this into a curse by causing her prophecies,

though true, to be disbelieved.

Naming that database “Cassandra” therefore, does not sound very smart in retrospect, but does sound surprisingly honest to me when I look back at my past experience with it. The latest curse which “The daughter of the Trojan king” has cast upon me is demanding to be moved from a classical deployment on EC2 Instances on AWS to deployment on kubernetes on AWS (eks). In my case, “existing multi-node data-intensive application” translates to cassandra and this is an overview of my solution and how I got to it.

Just a Cassandra

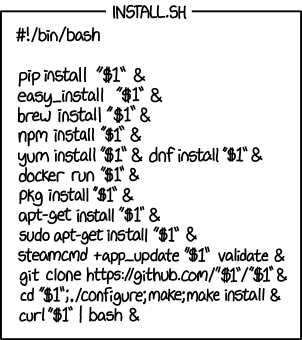

You can get yourself a vanilla cassandra by using the universal install script:

which suggests:

docker run --rm -it --name cassandra cassandra:3.0.10

Cassandra on Kubernetes

So kubernetes is all fun and games until you need to actually persist your data. The lack of “fun and games” translates to writing a few more lines of configuration if you’ve only used kubernetes hosted in third party clouds. Otherwise, it means you start to reconsider your whole kubernetes migration plan. Thankfully, in my current scenario, I have the chance to be naive and abstract persistence headaches away to AWS.

With that in place, you can get yourself a Cassandra cluster in the cloud fairly easily following the guide in Kubernetes documents. You’ll use StatefulSets to name the pods ordinally:

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: StatefulSet

metadata:

name: cassandra

labels:

app: cassandra

...

You’ll use PersistentVolumeClaims to ask for persistent storage:

volumeClaimTemplates:

- metadata:

- name: cassandra-data

...

And mount it on the correct path:

volumeMounts:

- name: cassandra-data

mountPath: /cassandra_data

...

That’s about it. Everything else is mostly application configuration.

An important point here is volume-pod affinity. That means after pod cassandra-2 gets deleted and recreated, it will be passed the same volume, both in the sense that its modifications on the volume will be persisted between restarts, and it won’t be handed a different pod’s volume. That means the application running inside the pod can correctly count on the hostname to stay consistent. There are a few pitfalls though. The most important being the fact that the IP addresses will not necessarily be preserved and an application instance is therefore not allowed to “think” in a lower level than the Cluster DNS when referring to its peers (cassandra-0 talks to cassandra-1.cassandra.default.svc.cluster.local, as opposed to talking to 192.168.23.50, as this IP address won’t be preserved through delete & restart of cassandra-1).

With that, you have pods running a cassandra cluster, which will tolerate failures on the node (pod) level and can be scaled up easily.

These give us an idea of what would the final state of things should look like. Now let’s try to reach this state, starting from the “legacy” setup: Three Bare EC2 Instances running cassandra with huge loads of data accumulated in each one’s block storage. The terminal state would hopefully be a functional cluster inside kubernetes, with all the data of course. I’m going to refer to the former as “the legacy cluster” and to the latter as “the new cluster”.

Moving to Kubernetes: First Attempt

The legacy database was under production load, so we didn’t really want to think of adding the new cluster nodes to the previous cluster, replicating the data to the new cluster, and then removing the legacy nodes. We wanted it to be clean and safe.

The first “safe” idea therefore was to use cassandra’s snapshot tool. On the legacy nodes:

nodetool flush # Ask cassandra to please flush to the persistent storage

nodetool snapshot -t snp-for-new-cluster $KEYSPACE

sstableloader -d new-node-1,new-node-2,new-node-3 /path/to/snapshot

Piece of cake, right?

Wrong!

This was transferring data to the new cluster with the rate of about One Million Bytes every second. Fortunately, we had amazing mathematicians in our team, who correctly pointed out that this would take months – a bit too much.

Moving to Kubernetes: Second Attempt

Well of course, network latency. Everyone knows about network latency. The next idea therefore was copying the data over to the new nodes and perform the loading of cassandra sstables from there. Unfortunately, we hit the 1MB/S again as we tried moving the snapshots to the new server over https. Another attempt was to mount a new empty ebs volume on a legacy instance and to copy the snapshot to the empty volume (to be brought over to the new cluster later on where we would execute sstableloader -d localhost ... to try to escape sstable over network). This attempt also failed miserably as the data transfer between ebs volumes was taking place as slow as 1MB/s.

Moving to Kubernetes: Third Attempt

We took a snapshot of the whole ebs volume and created a new volume from that. Fortunately, it finished (within hours). We attached the new volume to the new instances and ran sstableloader. Nope. Same problem.

Moving to Kubernetes: Fourth Attempt and Beyond

It seemed like the only plausible way to this would be using the exact snapshots in kubernetes without copying/loading/moving anything: To move a data-intensive application to kubernetes (in the aws context at least), it probably makes sense to create the cloud environment in a way that the application instance, given the correct data from its legacy state, would just work correctly without any further supervision. At that point, the problem to solve would just be moving the data to the cloud correctly (assuming you have previously solved the networking problem to make your distributed application cloud native), regardless of the actual application that is being moved. It is important to notice that we’re actually erasing a problem in a higher level (application) by attacking from a lower layer in the stack (storage).

To do this, we need to “feed” the replicated legacy volumes to the new cluster through kubernetes PersistentVolumes. Can we trick the StatefulSet controller into using our supplied volume instead of its own? Let’s look at the code:

// getPersistentVolumeClaimName gets the name of PersistentVolumeClaim

// for a Pod with an ordinal index of ordinal. claim

// must be a PersistentVolumeClaim from set's VolumeClaims template.

func getPersistentVolumeClaimName

(set *apps.StatefulSet, claim *v1.PersistentVolumeClaim, ordinal int) string {

// NOTE: This name format is used by the heuristics

// for zone spreading in ChooseZoneForVolume

return fmt.Sprintf("%s-%s-%d", claim.Name, set.Name, ordinal)

}

This is how the name of a PVC of an ordinal pod in the StatefulSet is inferred. This function is used later when the controller tries to find the correct volumes to attach to a pod:

// updateStorage updates pod's Volumes to conform with

// the PersistentVolumeClaim of set's templates. If pod has

// conflicting local Volumes these are replaced with Volumes

// that conform to the set's templates.

func updateStorage(set *apps.StatefulSet, pod *v1.Pod) {

currentVolumes := pod.Spec.Volumes

claims := getPersistentVolumeClaims(set, pod) // <- this guy indirectly calls

// the above function

newVolumes := make([]v1.Volume, 0, len(claims))

for name, claim := range claims {

newVolumes = append(newVolumes, v1.Volume{

Name: name,

VolumeSource: v1.VolumeSource{

PersistentVolumeClaim: &v1.PersistentVolumeClaimVolumeSource{

ClaimName: claim.Name,

Therefore, all the StatefulSet controller knows about the PVCs is names! That’s great! We can create our own PVCs from the PVs that we have created from the new volumes, and by naming the properly, we’re basically introducing our manual volume provisioning.

The first step is creating the PersistentVolumes. Here’s a gist:

kind: PersistentVolume

apiVersion: v1

metadata:

...

spec:

accessModes:

- ReadWriteOnce

awsElasticBlockStore:

volumeID: aws://us-east-1${AVAILABILITY_ZONE}/${VOL_ID}

fsType: ext4

...

Where we’re providing the volume id of the newly created volume that needs to be mounted on one of the new pods.

After that, we need to create a PVC from the above PV. Here are the important parts:

apiVersion: v1

kind: PersistentVolumeClaim

metadata:

...

name: cassandra-data-cassandra-${POD_NUMBER}

spec:

...

volumeName: custom-cassandra-pv-us-east-1${AVAILABILITY_ZONE}

The name, as we concluded, is of particular importance here.

At this point, you’re surprisingly almost done! You may also want to add particular labels to your custom volumes and corresponding selectors to the PVC template that goes inside the StatefulSet if you want absolute full control over how the storage is handled in a particular StatefulSet.