LINQ stands for Language Integrated Query. It provides a consistent strongly typed mechanism for querying data across various sources. LINQ is based on expressions. This article explores LINQ and underlying expressions by building a custom expression tree in a reference application.

LINQ stands for Language Integrated Query and is one of my favorite .NET and C# technologies. Using LINQ, developers can write queries directly in strongly typed code. LINQ provides a standard language and syntax that is consistent across data sources.

The Basics

Consider this LINQ query (you can paste this into a console application and run it yourself):

using System;

using System.Linq;

public class Program

{

public static void Main()

{

var someNumbers = new int[]{4, 8, 15, 16, 23, 42};

var query = from num in someNumbers

where num > 10

orderby num descending

select num.ToString();

Console.WriteLine(string.Join('-', query.ToArray()));

}

}

Because someNumbers is an IEnumerable<int>, the query is parsed by LINQ to Objects. The same query syntax can be used with a tool like Entity Framework Core to generate T-SQL that is run against a relational database. LINQ can be written using one of two syntaxes: query syntax (shown above) or method syntax. The two syntaxes are semantically identical and the one you use depends on your preference. The same query above can be written using method syntax like this:

var secondQuery = someNumbers.Where(n => n > 10)

.OrderByDescending(n => n)

.Select(n => n.ToString());

Every LINQ query has three phases:

- A data source is set up, known as a provider, for the query to act against. For example, the code shown so far uses the built-in LINQ to Objects provider. Your EF Core projects use the EF Core provider that maps to your database.

- The query is defined and turned into an expression tree. I’ll cover expressions more in a moment.

- The query is executed, and data is returned.

Step 3 is important because LINQ uses what is called deferred execution. In the example above, secondQuery defines an expression tree but doesn’t yet return any data. In fact, nothing actually happens until you start to iterate the data. This is important because it allows providers to manage resources by only delivering the data requested. For example, let’s assume you want to find a specific string using secondQuery, so you do something like this:

var found = false;

foreach(var item in secondQuery.AsEnumerable())

{

if (item == "23")

{

found = true;

break;

}

}

A provider can handle the enumerator so that it feeds data one element at a time. If you find the value on the third iteration, it is possible that only three items were actually returned from the database. On the other hand, when you use the .ToList() extension method, all data is immediately fetched to populate the list.

The Challenge

For my role as PM for .NET Data, I frequently speak to customers to understand their needs. Recently, I had a discussion with a customer who wants to use a third-party control in their website to build business rules. More specifically, the business rules are “predicates” or a set of conditions that resolve to true or false. The tool can generate the rules in JSON or SQL format. SQL is tempting to pass along to the database, but their requirement is to apply the predicates to in-memory objects as a filter on the server as well. They are considering a tool that translates SQL to expressions (it’s called Dynamic LINQ if you’re interested). I suggested that the JSON format probably is fine, because it can be parsed into a LINQ expression that is run against objects in memory or easily applied to an Entity Framework Core collection to run against the database.

The spike I wrote only deals with the default JSON produced by the tool:

{

"condition":"and",

"rules":[

{

"label":"Category",

"field":"Category",

"operator":"in",

"type":"string",

"value":[

"Clothing"

]

},

{

"condition":"or",

"rules":[

{

"label":"TransactionType",

"field":"TransactionType",

"operator":"equal",

"type":"boolean",

"value":"income"

},

{

"label":"PaymentMode",

"field":"PaymentMode",

"operator":"equal",

"type":"string",

"value":"Cash"

}

]

},

{

"label":"Amount",

"field":"Amount",

"operator":"equal",

"type":"number",

"value":10

}

]

}

The structure is simple: there is an AND or OR condition that contains a set of rules that are either comparisons, or a nested condition. My goal was twofold: learn more about LINQ expressions to better inform my understanding of EF Core and related technologies, and provide a simple example to show how the JSON can be used without relying on a third party tool.

One of my earliest open source contributions was the NoSQL database engine I named Sterling because I wrote it as a local database for Silverlight. It later gained popularity when Windows Phone was released with Silverlight as the runtime and was used in several popular recipe and fitness apps. Sterling suffered from several limitations that could have easily been mitigated with a proper LINQ provider. My goal is to ultimately master enough of LINQ to be able to write my own EF Core provider if the need arises.

The Solution: Dynamic Expressions

I created a simple console app to test my hypothesis that materializing the LINQ from the JSON would be relatively straightforward.

JeremyLikness/ExpressionGenerator

Set the startup project to ExpressionGenerator for the first part of this post. If you run it from the command line, be sure that rules.json is in your current directory.

I embedded the sample JSON as rules.json. Using System.Text.Json to parse the file is this simple:

var jsonStr = File.ReadAllText("rules.json");

var jsonDocument = JsonDocument.Parse(jsonStr);

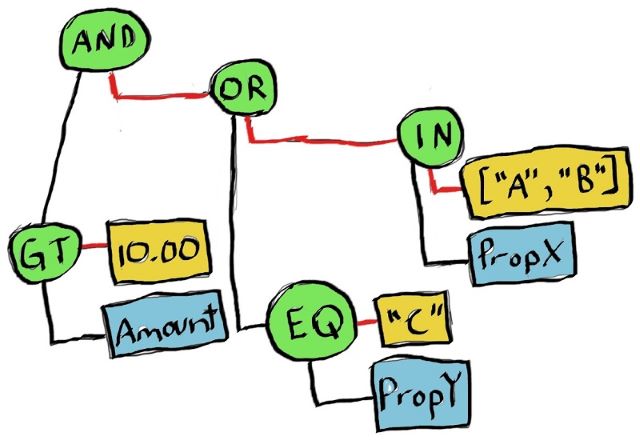

I then created a JsonExpressionParser to parse the JSON and create an expression tree. Because the solution is a predicate, the expression tree is built from instances of BinaryExpression that evaluate a left expression and a right expression. That evaluation might be a logic gate (AND or OR), or a comparison (equal or greaterThan), or a method call. For the case of In i.e., we want property Category to be in one of several items in a list, I flip the script and use Contains. Conceptually, the referenced JSON looks like this:

/-----------AND-----------\

| |

/-AND-\ |

Category IN ['Clothing'] Amount eq 10.0 /-OR-\

TransactionType EQ 'income' PaymentMode EQ 'Cash'

Notice that each node is binary. Let’s start parsing!

Introducing Transaction

No, this isn’t System.Transaction. This is a custom class used in the example project. I didn’t spend much time on the vendor’s site, so I guessed at what the entity might look like based on the rules. I came up with this:

public class Transaction

{

public int Id { get; set; }

public string Category { get; set; }

public string TransactionType { get; set; }

public string PaymentMode { get; set; }

public decimal Amount { get; set; }

}

I then added some additional methods to make it easy to generate random instances. You can see those in the code yourself.

Parameter Expressions

The main method returns a predicate function. Here’s the code to start:

public Func<T, bool> ParsePredicateOf<T>(JsonDocument doc)

{

var itemExpression = Expression.Parameter(typeof(T));

var conditions = ParseTree<T>(doc.RootElement, itemExpression);

}

The first step is to create the predicate parameter. A predicate can be passed to a Where clause, and if we wrote it ourselves, it would look something like this:

var query = ListOfThings.Where(t => t.Id > 2);

The t => is the first parameter and represents the type of an item in the list. Therefore, we create a parameter for that type. Then, we recursively traverse the JSON nodes to build the tree.

Logic Expressions

The start of the parser looks like this:

private Expression ParseTree<T>(

JsonElement condition,

ParameterExpression parm)

{

Expression left = null;

var gate = condition.GetProperty(nameof(condition)).GetString();

JsonElement rules = condition.GetProperty(nameof(rules));

Binder binder = gate == And ? (Binder)Expression.And : Expression.Or;

Expression bind(Expression left, Expression right) =>

left == null ? right : binder(left, right);

There’s a bit to digest. The gate variable is the condition, i.e., “and” or “or.” The rules statement gets a node that is the list of related rules. We are keeping track of the left and right side of the expression. The Binder signature is shorthand for a binary expression, and is defined here:

private delegate Expression Binder(Expression left, Expression right);

The binder variable simply sets up the top-level expression: either Expression.And or Expression.Or. Both take left and right expressions to evaluate.

The bind function is a little more interesting. As we traverse the tree, we need to build up the various nodes. If we haven’t created an expression yet (left is null) we start with the first expression created. If we have an existing expression, we use that expression to merge the two sides.

Right now, left is null, and then we start enumerating the rules that are part of this condition:

foreach (var rule in rules.EnumerateArray())

Property Expressions

The first rule is an equality rule, so I’ll skip the condition part for now. Here’s what happens:

string @operator = rule.GetProperty(nameof(@operator)).GetString();

string type = rule.GetProperty(nameof(type)).GetString();

string field = rule.GetProperty(nameof(field)).GetString();

JsonElement value = rule.GetProperty(nameof(value));

var property = Expression.Property(parm, field);

First, we get the operator (“in”), the type (“string”), the field (“Category”) and the value (an array with “Clothing” as the only element). Notice the call to Expression.Property. The LINQ for this rule would look like this:

var filter = new List<string> { "Clothing" };

Transactions.Where(t => filter.Contains(t.Category));

The property is the t.Category part, so we create it based on the parent property (t) and the field name.

Constant and Call Expressions

Next, we need to build the call to Contains. To simplify things, I created a reference to the method here:

private readonly MethodInfo MethodContains = typeof(Enumerable).GetMethods(

BindingFlags.Static | BindingFlags.Public)

.Single(m => m.Name == nameof(Enumerable.Contains)

&& m.GetParameters().Length == 2);

This grabs the method on Enumerable that takes two parameters: the enumerable to use and the value to check for. The next bit of logic looks like this:

if (@operator == In)

{

var contains = MethodContains.MakeGenericMethod(typeof(string));

object val = value.EnumerateArray().Select(e => e.GetString())

.ToList();

var right = Expression.Call(

contains,

Expression.Constant(val),

property);

left = bind(left, right);

}

First, we use the Enumerable.Contains template to create an Enumerable<string> because that is the type we are looking for. Next, we grab the list of values and turn it into a List<string>. Finally, we build our call, passing it:

- The method to call (

contains) - The value that is the parameter to check for (the list with “

Clothing”, or Expression.Constant(val)) - The property to check it against (

t.Category).

Our expression tree is already fairly deep, with parameters, properties, calls, and constants. Remember that left is still null, so the call to bind simply sets left to the call expression we just created. So far, we look like this:

Transactions.Where(t => (new List<string> { "Clothing" }).Contains(t.Category));

Iterating back around, the next rule is a nested condition. We hit this code:

if (rule.TryGetProperty(nameof(condition), out JsonElement check))

{

var right = ParseTree<T>(rule, parm);

left = bind(left, right);

continue;

}

Currently, left is assigned to the “in” expression. right will be assigned as the result of parsing the new condition. I happen to know it’s an OR condition. Right now, our binder is set to Expression.And so when the function returns, the bind call leaves us with:

Transactions.Where(t => (new List<string> { "Clothing" }).Contains(t.Category) && <something>);

Let’s look at “something”.

Comparison Expressions

First, the recursive call determines a new condition exists, this time a logical OR. The binder is set to Expression.Or and the rules begin evaluation. The first rule is for TransactionType. It is set as boolean but from what I infer, it means the user in the interface can check to select a value or toggle to another value. Therefore, I implemented it as a simple string comparison. Here’s the code that builds the comparison:

object val = (type == StringStr || type == BooleanStr) ?

(object)value.GetString() : value.GetDecimal();

var toCompare = Expression.Constant(val);

var right = Expression.Equal(property, toCompare);

left = bind(left, right);

The value is deconstructed as a string or decimal (a later rule will use the decimal format). The value is then turned into a constant, then the comparison is created. Notice it is passed the property. The variable right now looks like this:

Transactions.Where(t => t.TransactionType == "income");

In this nested loop, left is still empty. The parser evaluates the next rule, which is the payment mode. The bind function turns it into this “or” statement:

Transactions.Where(t => t.TransactionType == "income" || t.PaymentMode == "Cash");

The rest should be self-explanatory. A nice feature of expressions is that they overload ToString() to generate a representation. This is what our expression looks like (I took the liberty of formatting for easier viewing):

(

(value(System.Collections.Generic.List`1[System.String]).Contains(Param_0.Category)

And (

(Param_0.TransactionType == "income")

Or

(Param_0.PaymentMode == "Cash"))

)

And

(Param_0.Amount == 10)

)

It looks good… but we’re not done yet!

Lambda Expressions and Compilation

The expression tree represents an idea. It needs to be turned into something material. In case the expression can be simplified, I reduce it. Next, I create a lambda expression. This defines the shape of the parsed expression, which will be a predicate (Func<T,bool>). Finally, I return the compiled delegate.

var conditions = ParseTree<T>(doc.RootElement, itemExpression);

if (conditions.CanReduce)

{

conditions = conditions.ReduceAndCheck();

}

var query = Expression.Lambda<Func<T, bool>>(conditions, itemExpression);

return query.Compile();

To “check my math” I generate 1000 transactions (weighted to include several that should match). I then apply the filter and iterate the results so I can manually test that the conditions were met.

var predicate = jsonExpressionParser

.ParsePredicateOf<Transaction>(jsonDocument);

var transactionList = Transaction.GetList(1000);

var filteredTransactions = transactionList.Where(predicate).ToList();

filteredTransactions.ForEach(Console.WriteLine);

As you can see, the results all check out (I average about 70 “hits” each run.)

Beyond Memory to Database

The generated delegate isn’t just for objects. We can also use it for database access.

Set the startup project to DatabaseTest for the rest of this post. If you run it from the command line, be sure that databaseRules.json is in your current directory.

First, I refactored the code. Remember how expressions require a data source? In the previous example, we compile the expression and end up with a delegate that works on objects. To use a different data source, we need to pass the expression before it is compiled. That allows the data source to compile it. If we pass the compiled data source, the database provider will be forced to fetch all rows from the database, then parse the returned list. We want the database to do the work. I moved the bulk of code into a method named ParseExpressionOf<T> that returns the lambda. I refactored the original method to this:

public Func<T, bool> ParsePredicateOf<T>(JsonDocument doc)

{

var query = ParseExpressionOf<T>(doc);

return query.Compile();

}

The ExpressionGenerator program uses the compiled query. The DatabaseTest uses the raw lambda expression. It applies it to a local SQLite database to demonstrate how the expression is parsed by EF Core. After creating and inserting 1000 transactions into the database, the code retrieves a count:

var count = await context.DbTransactions.CountAsync();

Console.WriteLine($"Verified insert count: {count}.");

This results in the following SQL:

SELECT COUNT(*)

FROM "DbTransactions" AS "d"

If you’re wondering why there are two contexts, it is due to logging. The first context inserts 1000 records and if logging is turned on, it will run very slow as the inserts are written to the console. The second context switches on logging so you can see the evaluated statement.

The predicate is parsed (this time from a new set of rules in databaseRules.json) and passed to the Entity Framework Core provider.

var parser = new JsonExpressionParser();

var predicate = parser.ParseExpressionOf<Transaction>(

JsonDocument.Parse(

await File.ReadAllTextAsync("databaseRules.json")));

var query = context.DbTransactions.Where(predicate)

.OrderBy(t => t.Id);

var results = await query.ToListAsync();

With Entity Framework Core logging turned on, we are able to retrieve the SQL and see the items are fetched in one pass and evaluated in the database engine. Notice the PaymentMode is checked for “Credit” instead of “Cash”.

SELECT "d"."Id", "d"."Amount", "d"."Category", "d"."PaymentMode", "d"."TransactionType"

FROM "DbTransactions" AS "d"

WHERE ("d"."Category" IN ('Clothing') &

((("d"."TransactionType" = 'income') AND "d"."TransactionType" IS NOT NULL) |

(("d"."PaymentMode" = 'Credit') AND "d"."PaymentMode" IS NOT NULL))) &

("d"."Amount" = '10.0')

ORDER BY "d"."Id"

The example app also prints one of the selected entities to spot-check.

Conclusion

LINQ expressions are a very powerful tool to filter and transform data. I hope this example helped demystify how expression trees are built. Of course, parsing the expression tree feels a little like magic. How does Entity Framework Core walk the expression tree to produce meaningful SQL? I’m exploring that myself and with a little help from my friend, ExpressionVisitor. More posts to come on this!

Regards,