Python is the premier programming language of AI and machine learning. This article will introduce you to important Python basics including: Where to get Python, the difference between Python 2 and Python 3, and how familiar language concepts like syntax and variables work in Python.

Introduction

When developers begin working with artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) software, the programming languages they're most likely to encounter today are Python and C/C++. Most of the time, C/C++ is used in specialized applications such as with embedded Internet of Things (IoT) and highly optimized, hardware-specific neural network libraries.

Python is the most commonly used language for most AI and ML application development — even for prototyping and optimizing models for those IoT and hardware-accelerated applications.

For developers coming to Python from other languages such as C#, Java, and even JavaScript, this article introduces you to key elements of Python’s unique syntax, such as loops, and how they differ from what you might know.

Additional articles in this series will explore how to work with numerous Python libraries available for AI and ML developers such as OpenCV, Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK), Keras, and TensorFlow.

This article will introduce you to important Python basics including:

- Where to get Python

- The difference between Python 2 and Python 3

- How familiar language concepts like syntax and variables work in Python

Where to Get Python

The first question developers usually ask is: where do I get Python?

The answer is: it depends on your system and programming environment. Python is installed by default on Mac OS and some Linux distributions. For systems that do not have Python, you can get the installer from:

Another choice is the Jupyter Notebooks and JupyterLabs interactive development tools.

A third choice — and the one we recommend and will use for these Python AI/ML articles — Anaconda, a comprehensive software platform designed specifically for statistics, data science, and AI/ML projects.

Anaconda includes JupyterLab, the web-based IDE mentioned earlier, along with many of the other tools, libraries, and sample data sources you're likely to need when learning about AI. Once we get to machine learning libraries, datasets, and visualizations, you’ll find them helpful.

Which Version: Python 2 or Python 3?

Whether to use Python 2 or Python 3 is a common source of confusion for people new to the language.

Python 2 is an older version that’s still used fairly often, and is still installed as the default version of Python in some current operating systems. Official support for Python 2 will end in the beginning of 2020.

If you’re just starting with Python, you should use Python 3.

Ongoing support and development is continuing for Python 3. That also goes for libraries you might want to use: some may still support both versions, but many will have moved to Python 3 completely or are likely to do so.

How do you know which version is installed on your system?

On Linux systems and Mac OS, the python command defaults to Python 2 and you use the python3 command for Python 3.

To figure out which version is installed on your system, go to a terminal window or command prompt and run the command:

python --version

If Python is installed, it returns the version of Python used by the python command.

Python 2.7.16

The python3 --version command does the same for Python 3.

Python 3.7.4

Recognizing the Python Version in Code Examples

Online tutorials don’t always explicitly mention whether they use Python 2 or Python 3. Fortunately, there are a couple of heuristics you can use to figure out which version a tutorial employs.

One is the difference in how text is printed on the standard output. In Python 3, there’s only one valid way to do so:

print("Hello, world!")

That syntax is also valid in Python 2, but Python 2 examples much more commonly use this alternative syntax:

print "Hello, world!"

And that's invalid in Python 3. So a print statement without parentheses is a clear tell that code is written in Python 2.

Another common tell is how the code takes input through stdin.

In Python 3, reading raw input is done with the input function.

In Python 2, the input function also exists, but there it evaluates the input as Python code and returns the result.

For raw input, Python 2 uses raw_input. This function doesn’t exist in Python 3.

If a code snippet doesn’t interact with standard output/input, you can look at features used from the standard library. A list of the features that have changed in Python 3 would lead us too far here, but you can take a look at The Conservative Python 3 Porting Guide for a more complete list.

All that said, much code written in Python 2 will work fine in Python 3. When in doubt about a code snippet, give it a shot and run it in Python 3. If it doesn't work because of the Python version, searching online for the error message will quickly point that out.

Python Language Basics: Types and Variables

Python is dynamically typed. Types are not associated with variable names, only with the variable values. This differs from statically typed languages such as C# and Java where, if you define int i = 0;, you can’t write i = "test"; later. In Python, you can.

Python is strongly typed (as opposed to, for example, JavaScript, which is weakly typed). In strongly typed languages, there are stricter constraints on operations between values of different types. In JavaScript, you can do "abc" + 1 and end up with a string "abc1", but if you try the same in Python, you'll get an error indicating you can’t concatenate strings with integers.

Assigning a variable in Python can be done like this:

name = "value"

Note that lines don’t end with a semicolon.

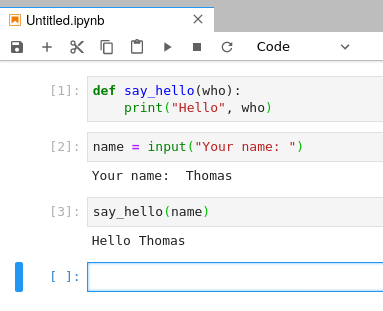

Defining and calling a function looks like this:

def say_hello(who):

print("Hello ", who)

name = input("Your name: ")

say_hello(name)

And here’s what it looks like in a Jupyter Notebook:

Unlike languages such as C#, Python doesn’t use brackets to specify which lines of code belong to a function. Instead, Python uses indentation. A sequence of lines with the same indentation level forms a block. The recommended way to indent your code is to use four spaces per indentation level. However, you can also use tabs or another number of spaces. The indentation only has to be consistent within a block.

You can return a value from a function using the return keyword:

def sum(a, b):

return a + b

If a function doesn’t have a return statement, it will return None (Python's null).

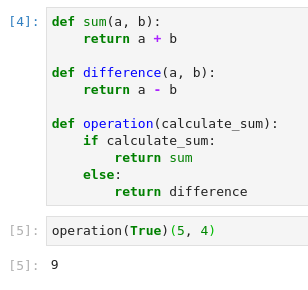

Python supports higher-order functions (functions that return functions or take a function as an argument) as well. For example, the operation function returns one of two functions:

def sum(a, b):

return a + b

def difference(a, b):

return a - b

def operation(calculate_sum):

if calculate_sum:

return sum

else:

return difference

Which can then be used this way:

operation(True)(5, 4)

Conclusion

We talked about the difference between Python 2 and Python 3 and saw how you can recognize which version was used in a code snippet. Then we looked at some basics of Python: typing, variables, and functions.

In the next article, we'll talk about lists, tuples, and loops!

History

- 12th June, 2020: Initial version