Python offers lists and tuples as data structures for collections. This module talks about these and how you can use them with destructuring and loops.

Introduction

This is the second module in our series to help you learn about Python and its use in machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI).

Now that you know some of the basics of Python, which were discussed in the first module, we can go a bit deeper, with the lists and tuples data structures and see how to work with them.

Lists

A list is a collection of items. Lists are mutable: you can change their elements and their size. Thus they’re similar to a List<T> in C#, an ArrayList<T> in Java, and an array in JavaScript.

You can assign a list like this, and then access its elements by their zero-based index:

foo = [1, 2, True, "mixing types is fine"]

print(foo[0])

foo[0] = 3

print(foo[0])

The append method adds an element at the end of the list. The insert method places an element at an index you specify:

foo = [1, 2, 3]

foo.append(4)

print(foo)

foo.insert(0, 0.5)

print(foo)

To remove an element at an index, use the del keyword:

del foo[2]

print(foo)

Tuples

A tuple is another type of collection of items. Tuples are similar to lists, but they’re immutable. A tuple gets assigned like this:

foo = 1, 2, True, "you can mix types, like in lists"

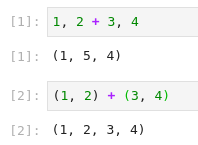

You'll often see tuples formatted as (1, 2, "a"), with parentheses. Parentheses around tuple values are used to help with readability or if needed because of the context. For example, 1, 2 + 3, 4 means something different than (1, 2) + (3, 4)! The first expression returns a tuple (1, 5, 4) while the second returns (1, 2, 3, 4).

Obtaining a value from a tuple works in the same way as from a list, foo[index], with index denoting the zero-based index of the element. You can see that tuples are immutable if you try to change one of the elements:

foo[0] = 3

That would work fine for a list, but not for a tuple.

A tuple also doesn't have the append, remove, and some other methods.

You can also return tuples from functions, and this is a common practice:

def your_function():

return 1, 2

This returns a tuple (1, 2).

If you want a tuple with only one element, put a comma after that element:

foo = 1,

Negative Indices and Slices

Python's indices are more powerful than I've demonstrated so far. They offer some functionality that doesn’t exist in C#, Java, and the like. An example is negative indices, in which -1 refers to the last element, -2 refers to the second-last element, and so on.

my_list = [1, 2, 3]

print(my_list[-1])

This works on both lists and tuples.

Also, you can take a slice of a list or a tuple by specifying the index of the starting, ending, or both starting and ending elements of the slice. This generates a new list or tuple with a subset of the elements. Here are a few examples to demonstrate:

my_list = [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

print(my_list[1:2])

print(my_list[2:])

print(my_list[:2])

print(my_list[0:4:2])

print(my_list[-3:-1])

print(my_list[::-1])

The slice notation is [start:stop:step]. If start remains empty, it's 0 by default. If end remains empty, it means the end of the list. The :step notation is optional. So ::-1 means "from 0 to the end of the list with step -1" and thus returns the list reversed.

Slices will never raise IndexErrors. When going out of range, they just return an empty list.

Destructuring

Imagine you have a tuple (or a list) with a known number of elements, three for example. And suppose you'd rather have three distinct variables, one for each tuple element.

Python offers a feature called destructuring (or unpacking) to break up a collection with a single line:

my_tuple = 1, 2, 3

a, b, c = my_tuple

Now a = 1, b = 2, and c = 3.

This also works for lists:

my_list = [1, 2, 3]

a, b, c = my_list

This is very useful when dealing with functions that return tuples, and there are plenty of these in the Python ecosystem, as well as when dealing with AI-related libraries.

Loops

You're probably familiar with three kinds of loops: for, foreach, and while. Python only offers while and foreach loops (which it does with a for keyword!). No worries, though. As we'll see later, it's very easy to create a loop that behaves exactly like a for loop.

Here’s a Python loop that iterates over a list:

fruits = ["Apple", "Banana", "Pear"]

for fruit in fruits:

print(fruit)

You can also iterate over tuples:

fruits = "Apple", "Banana", "Pear"

for fruit in fruits:

print(fruit)

Generally, you can use a for loop on every iterator. Iterators, and how you can create your own, will be discussed in more depth in later articles.

If you want a C-style for loop rather than a foreach loop, you can loop over the result of the range function, which returns an iterator over a range:

for i in range(10):

print(i)

The last printed number will be 9. This is equivalent to the following C snippet:

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

Console.WriteLine(i);

}

The range function offers more than just counting from zero up to a given number. You can specify a different starting number using range(x, 10), where x will be the first array element. You can specify the step size using a third argument, such as range(0, 10, 2).

Creating a range that counts from high to low goes like this: range(10, 0, -1). The first element will now be 10 and the last will be 1. Indeed, range(0, 10) is not the reverse of range(10, 0, -1), because the second argument won’t be included in the range.

A while loop in Python looks very similar to what you already know:

while condition:

Python also offers break and continue statements that work exactly like the ones in C#, Java, JavaScript, and many other languages.

while True:

if input() == "hello":

break

Conclusion

In this module, we looked at lists and tuples in Python, and learned about indexing, destructuring, and loops. In the next article, we'll talk about generators and classes.