In this article, you will learn about the basic math behind the ADALINE perceptron.

Contents

Introduction

A lot of articles introduce the perceptron showing the basic mathematical formulas that define it, but without offering much of an explanation on what exactly makes it work.

And surely it is possible to use the perceptron without really understanding the basic math involved with it, but is it not also fun to see how all this math you learned in school can help you understand the perceptron, and in extension, neural networks?

I also got inspired for this series of articles by a series of articles on Support Vector Machines, explaining the basic mathematical concepts involved, and slowly building up to the more complex mathematics. So that is my intention with this article and the accompanying code: show you the math involved in the perceptron. And, if time permits, I will write articles all the way up to convolutional neural networks.

Of course, when explaining the math, the question is: when do you stop explaining? There is some math involved that is rather basic, like for example what is a vector?, what is a cosine?, etc. I will assume some basic knowledge of mathematics like you have some idea of what a vector is, you know the basics of geometry, etc. My assumptions will be arbitrary, so if you think I’m going too fast in some explanations, just leave a comment.

So, let us get started.

The Series

- The Math behind Neural Networks: Part 1 - The Rosenblatt Perceptron

- The Math behind Neural Networks: Part 2 - The ADALINE Perceptron

- The Math behind Neural Networks: Part 3 - Neural Networks

- The Math behind Neural Networks: Part 4 - Convolutional Neural Networks

Disclaimer

This article is about the math involved in the perceptron and NOT about the code used and written to illustrate these mathematical concepts. Although it is not my intention to write such an article, never say never…

Setting Some Bounds

A perceptron basically takes some input values, called “features” and represented by the values \(x_1, x_2, ... x_n\) in the following formula , multiplies them by some factors called “weights”, represented by \(w_1, w_2, ... w_n\), takes the sum of these multiplications and depending on the value of this sum outputs another value \(o\):

$o = f(w_1x_1 + w_2x_2 + ... + w_ix_i + ... + w_nx_n)$

There are a few types of perceptrons, differing in the way the sum results in the output, thus the function \(f()\) in the above formula.

In this article, we will build on the Adaline Perceptron. Adaline stands for Adaptive Linear Neuron. During this article I will simply be using the name “Perceptron” when referring to the Adaline Perceptron. I assume you have read the article about the Rosenblatt Perceptron and thus are already familiar with the basic vector math necessary to understand the basic formulas of a general perceptron.

We will investigate the math involved and discuss its limitations, thereby setting the ground for the future articles.

There’s not a big difference between the math formula for the Rosenblatt perceptron and for the ADALINE perceptron:

$f(x) = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } w_1x_1 + w_2x_2 + ... + w_ix_i + ... + w_nx_n > b\\ -1 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} $

The main difference is that the \(otherwise\) case returns \(-1\) instead of \(0\) which is important here.

But we still calculate the dot-product and compare it with a value, so we still only have two possible outcomes and we still can only classify linearly separable data. So, basically we can do nothing more than what we could do with the Rosenblatt perceptron.

So then why do we need a new perceptron?

Why Do We Need Another Perceptron?

In the previous article about the Rosenblatt perceptron, we were eventually able to divide “things” into two different classes through a linear combination of its features. What can we want more?

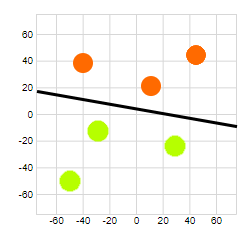

Well, a better estimate of the linear boundary would be nice. With the Rosenblatt perceptron, we do not have any control over the boundary which the learning will eventually give us: as demonstrated in the previous article, it could be any line which separates our two classes:

Remember the learning procedure of the Rosenblatt perceptron. We defined the error \(e\) as being the difference between the desired output \(d\) and the effective output \(o\) for an input vector \(\mathbf{x}\) and a weight vector \(\mathbf{w}\):

$\begin{aligned} e &= d-o\\ &= d-H(\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x}) \end{aligned}$

(If the above formulas look like Chinese to you, you should have a look at the article about the Rosenblatt perceptron.)

The effective output \(o\) is determined by the Heaviside step function, represented by \(H()\) in the formula above. We could define a cost function using this error and then try to minimize this cost function. A cost function is basically a function which calculates the total error of our model with respect to the desired values, so by minimizing the result of the cost function, we minimize the error.

The cost function for the ADALINE perceptron is based on the Sum of Squared Errors / Mean Sum of Squared Errors which in our case (linear regression) is part of a category of optimization algorithms called Convex Optimization.

Sum of Squared Errors, Convex Optimization: What Are You Talking About?

If you search the internet on information about the ADALINE perceptron, you’re likely to find various definitions for the learning rule. The original learning rule was the Least Mean Squares filter, also known as the Widrow-Hoff learning rule named after it’s inventors. However, in our digital computers age, you will also find references to the Sum of Squared Errors method. In the following section, you’ll see they basically boil down to the same underlying idea.

Sum of Squared Errors

We try to optimize (that is, minimize) the sum of the squared errors. The errors are defined in a similar fashion as for the Rosenbatt perceptron, but here we use the outcome of the dot-product immediately:

$\begin{aligned} e &= d-o\\ &= d-\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x} \end{aligned}$

Then we define the cost function as the sum of the squares of those errors:

$E(w) = \frac{1}{2} \sum_{j=1}^{M} e_j^2$

in which \(M\) is the number of samples. Thus, we take the sum over all our samples.

Never mind the division by \(2\), this is to get a convenient function later which we can solve. This will become clear after we discussed derivation.

But why squared?

If you search the internet for an explanation, then most probably you’ve read something along the lines of:

Because we want all positive values

This is true: we do indeed want positive values. Imagine we just take the sum of the errors. We would have positive and negative values which would cancel each other out. So the summation would become smaller (possibly even zero) although our solution would not be optimal. If we first make positive values of our errors and take the summation of those, then the only way to get zero as a result is if the results of our perceptron are equal to those of our samples. That is: if we have no errors.

Try it yourself:

Sum of Squared Errors versus Sum of Errors interactive

Ok, but then why not simply take the absolute value of our error? Asking the internet mostly returns:

Because large errors take a bigger share in the result.

Because taking the absolute value does not allow to take the derivative

To understand the last reason, we will need to understand convex optimization.

Above is not a mathematical rigorous explanation of why to use the Sum Of Squared Errors. There is a rigorous explanation involving things like likelihood, maximum likelihood, etc… This however is a pretty big subject and we already have a lot to explain, which is why I will not explain this any further in this article. But I do intend to provide a separate article detailing what this is about.

As mentioned above, you’ll also find definitions for the learning procedure which use the Mean Sum of Squared Error:

$E(w) = \frac{1}{2M} \sum_{j=1}^{M} e_j^2$

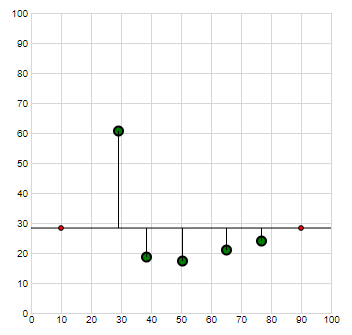

The original definition for the ADALINE perceptron used this definition. For optimizing, it does not make any difference if we use the Sum of Squared or Mean Sum of Squared Errors (as we’ll soon see), however, if we want to compare the results depending on the samples taken, it can make a difference if the number of samples for which we want to compare the results differ. See the next paragraph:

The Calculation of Squared Somethings

When you start searching the internet for information on the sum of squared errors, you’ll find all sorts of things done with squared somethings. It’s easy to get lost: I sure did. So let us briefly examine some combinations and see why we end up using the sum of squared errors:

- Least Squares Error This is a method for determining our model. We try to minimize (Least) the Sum of Squares of the Errors.

- Residual Sum of Squares This is basically the same as the Sum of Squared Errors. Instead of using the name Errors, we use the name Residuals.

- Ordinary Least Squares If our model is a linear model (which for the perceptron it is), then this is the same is the Least Squares Error. So, this also is a method for determining our model, but specialized for linear models.

- Mean Squared Error The mean squared errors calculates the mean of the squared errors. The mean is calculated by taking the sum of all the errors of our samples and dividing it by the number of samples, thus, it basically is the Least Squares Error divided by the number of samples. It is a good measure for evaluating the quality after we have calculated our weights. By taking the mean of the squared errors, we take the number of samples we want to check into account. Just imagine not dividing by the number of samples in the above formula: it would be clear that the higher the number of samples, the higher the sum of the squares would become and thus would hide the desired metric.

Try it yourself:

Sum of Squared Errors versus Sum of Mean Errors interactive

Convex Optimization

In convex optimization, we try to minimize a convex function.

What is a Convex Function?

From Wikipedia:

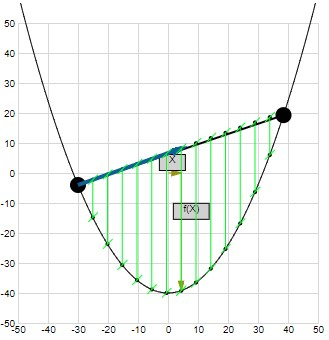

… is called convex if the line segment between any two points on the graph of the function lies above or on the graph. Equivalently, a function is convex if (…) the set of points on or above the graph of the function is a convex set.

(If you are not familiar with the concepts of line segments and convex sets, you should check out the first article in this series where I discuss the two.)

Using math, this definition becomes:

$f( \lambda A + (1- \lambda)B) \leq \lambda f(A) + (1- \lambda)f(B)$

in which \(A\) and \(B\) are two points in \(\mathbb{R}^n\) and \(\lambda\) is in the interval \((0, 1)\)

In words, this formula states that for a convex function, every value of the function on the “hyper-line” between the input points \(A\) and \(B\) must be smaller than the corresponding point on the “hyper-line” connecting the two results of the function for the points \(A\) and \(B\). If you are unfamiliar with the concept of line segments (from which this formula derives) you should read the section on line segments in the first article of this series

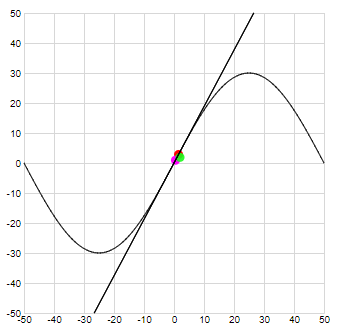

Following illustrates this formula:

Try it yourself:

Sum of Squared Errors versus Sum of Mean Errors interactive

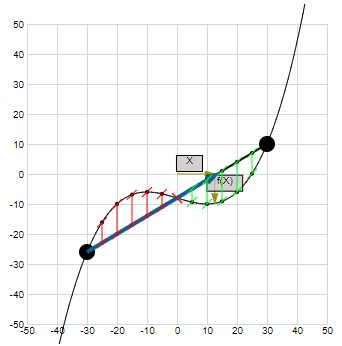

Following is an example of when the formula does NOT hold:

Try it yourself:

Sum of Squared Errors versus Sum of Mean Errors interactive

You may ask yourself what happens if the line segment is completely underneath the graph of the function. Then we have a concave function. It will be clear that this is just the convex function negated, thus if \(f(x)\) is a convex function, then \(-f(x)\) is a concave function.

Our cost function, the sum of squared errors, is a convex function.

What is Optimization?

What is interesting about a convex function is that it has a single minimum value. So, if our cost function of the perceptron is a convex function, then we can find a single minimum value for this function and thus we have a single optimal solution to our problem.

This is the main difference of the ADALINE perceptron with respect to the Rosenblatt perceptron: we can find a guaranteed optimal solution which will always be the same for a given set of samples. We will also find a solution when the learning data is not strictly separable, although this will not necessarily be a correct solution: some points may end up in the wrong half-space. But the error will be minimal.

So, the act of optimization in this case is to find for what arguments the cost function has a minimum value.

Finding the Minimum of a Function

Let us first mathematically define what a minimum is:

$a \in \mathbb{R}\text{ is a minimum for a function }f(x)\\ \text{ if for all points }x\text{ in a region around }a\text{ we have }f(x) >= f(a)$

We can extend this definition to functions of multiple variables:

$A = (a_1, a_2, ..., a_n) \in \mathbb{R^n}\text{ is a minimum for a function }f(x_1, x_2, ..., x_n)\\ \text{ if for all vectors }X\text{ in a region around }A\text{ we have }f(X) >= f(A)$

In words: we have a minimum for a function if all the neighbouring values of the function are larger then this minimum value.

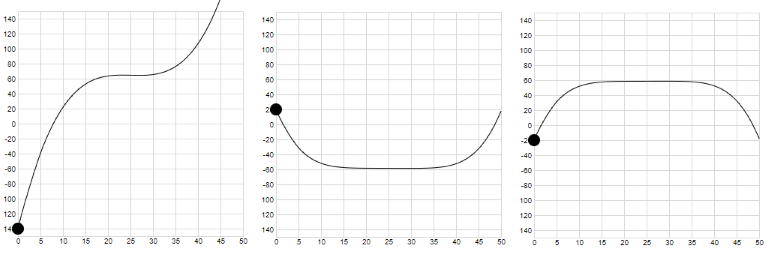

Finding this minimum is typically done by calculating the derivative of the function. As we will show later, the derivative of a function can be seen as the slope of that function. Or: the derivative of a function at a certain point is equal to the slope of the tangent to the function at that point.

This can be easily shown graphically for function of a single variable:

When the slope (thus the derivative) of a function is zero, thus when the tangent is horizontal, we typically have a minimum, maximum value or a horizontal inflection point:

Because our cost function is convex, we know we will have a minimum.

Although the above intuïtively feels ok, a more formal explanation can be found in Fermat’s_theorem_on stationary_points, but we’ll get back to this later.

So, to find the minimum, we have to find where the slope is \(0\) , and because the slope is the derivative (we’ll see why in the next section), we have to be able to find the derivative of the function.

But herein is the problem with regard to the Rosenblatt perceptron: for differentiation (which is the act af calculating the derivative), a function has to be continuous and the Heaviside step function is not continuous.

The ADALINE perceptron however defines the error as being the difference between the desired outcome \(d\) and the value of the dot-product, thus the value before applying the activation function:

$e = d-\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x}$

And this is continuous and thus differentiable.

But let us step back a bit and first explain what is the meaning of “differentiable” and “continuous”.

Differentiatable, Continuous? Any Other New Words You’d Like to Drop?

The Derivative of a Single Variable Function

Let’s say we have a function with a single variable:

$y = f(x)$

The operation of taking the derivative is called differentiation. The mathematical definition of the derivative is:

$f'(x) = \lim_{h\to0}\frac{f(x+h) - f(x)}{h}$

Notice the accent (\('\)) on the \(f\): this means the derivative

Another notation is sometimes used:

$\frac{df}{dx}$

in which we can interpret the \(d\) as meaning a small change. So the derivative is a small change in the outcome of a function divided by a small change in the argument of that function. Hence, the derivative of a function at a certain point is the slope of that function at that point: it gives a measure for how much the output of the function changes for a certain change of the input at a certain point.

Too make it explicit in the above definition, we could write:

$\begin{aligned} f'(x) &= \lim_{h\to0}\frac{f(x+h) - f(x)}{(x+h) - x}\\ &=\lim_{h\to0}\frac{f(x+h) - f(x)}{h} \end{aligned}$

What is this \(\lim_{h\to0}\) thing?

Understanding the Limit of a Function

In general, when we write:

$\lim_{x\to{c}}f(x) = L$

we mean the value the function \(f(x)\) takes as \(x\) approaches \(c\)

From Wikipedia:

\(f(x)\) can be made to be as close to \(L\) as desired by making \(x\) sufficiently close to \(c\). In that case, the above equation can be read as "the limit of \(f\) of \(x\), as \(x\) approaches \(c\), is \(L\)

It does NOT mean that \(x\) becomes equal to \(c\) !!! So, it is approaching within a very small range without ever reaching it. This “approaching” is (for our simple function \(y = f(x)\)) from both sides of the value \(c\).

A mathematical more rigorous definition is known as the (ε, δ)-definition of limit.

Let \(I\) be an open interval containing \(c\) (an interval basically being two numbers and all the numbers in-between them. “Open” meaning not containing the bounding two numbers and “closed” containing the two bounding numbers), and let \(f\) be a function defined on \(I\) (thus \(f(x)\) having an outcome for each number between the interval its bounding numbers), except possibly at \(c\)

Let \(\delta\) and \(\epsilon\) be two positive numbers:

$\begin{aligned} \delta &\in \mathbb{R}_{>0}\\ \epsilon &\in \mathbb{R}_{>0} \end{aligned}$

Then we can write:

$\lim_{x\to{c}}f(x) = L$

Means that for all \(x \ne c\)

$\lvert x−c \lvert < \delta \implies \lvert f(x)−L\lvert < \epsilon$

So what we are saying here is that for every \(\epsilon\) there is a \(\delta\) such that the above formula holds. The \(\epsilon\) part in this mathematical definition takes care of the \(f(x)\) can be made to be as close to \(L\) as desired part in the wikipedia definition, and \(\delta\) takes care of the by making \(x\) sufficiently close to \(c\) part.

There are however a few things to notice here:

First, we take the absolute value of the difference. This means that when we say \(x\to{c}\), we mean we approach \(c\) from every direction. On a linear scale, this means from both the right side and the left side.

Second: we say smaller than and NOT smaller than or equal to which corresponds with the statement in the definition of the function above:

and let \(f\) be a function defined on \(I\), except possibly at \(c\)

There is no need for the function to be defined at the value the limit is approaching to, because we never really get to this value! We just approach it or get as close to it as possible from every direction. Mind however this is only at the value itself! It has to be defined around the value.

Try it yourself:

Limit of a function interactive

Understanding the Derivative

Getting back to our derivative: simply put, it is the change in the result of a function divided by the change in the argument of that function, for a change in argument going to (approaching) \(0\) but not equal to \(0\).

Remember how we said for calculating the limit, the function does not have to be defined at the value to which we approach? For calculating the derivative, it does have to be. Not only that, it also has to be Continuous.

For a function to be differentiable, the derivative must exist at all points of its domain. And for a function to be differentiable at a point, it must be continuous at that point.

Continuity of a function is defined by the mathematical expression.

$\lim_{x\to{c}}f(x) = f(c)$

Or in words: a function is continuous at a point \(c\) if the limit of the function approaching that point is equal to the value of the function at that point. Notice how this is in contrast with the definition of the limit itself in which we said the function does not even have to be defined at \(c\).

Intuitively, you can see this as filling a gap: around \(c\) we have a certain value and we say that at \(c\) we want the same value.

So why is this a necessary condition for differentiability?

This has to do with being able to divide by \(0\).

Let us get back to the mathematical definition of differentiation:

$f'(x) = \lim_{h\to0}\frac{f(x+h) - f(x)}{h}$

If we take the differentiation at a certain point, we can also write this as:

$f'(x) = \lim_{x\to{a}}\frac{f(x) - f(a)}{x-a}$

Following is NOT a rigorous mathematical explanation, but rather a “gut feeling” explanation

If we take the value of the denominator for \(x\to{a}\), then this value is going to (approaching) \(0\). This means the result of the quotient is getting larger and larger and for the value \(0\) it is infinite. The only way to avoid this quotient reaching infinity is by making sure the nominator itself is also approaching \(0\). And thus, for \(x\to{a}\), the value of \(f(x)\) must go to \(f(a)\) which is exactly the definition of continuity given above:

$\lim_{x\to{a}}f(x) = f(a)$

A more mathematically rigorous proof can be found in the references section.

Try it yourself:

Continuity

Try it yourself:

Derivation

The Derivative of a Multiple Variable Function: The Directional Derivative

Of course, our function can be dependent on more than one argument and a single outcome \(y\):

$y = f(x_1,x_2,...,x_n)$

In this case, the slope becomes gradient and is calculated in a certain direction. We speak of the directional derivative:

We define the directional derivative in the direction \(u\), with \(\hat{u}\) the unit vector in the direction of \(u\) or \(\hat{u} = \frac{u}{\lvert\lvert{u}\lvert\lvert}\), as:

$\begin{aligned} {f'} _u &= \lim_{h\to0}\frac{f(x+h\hat{u}) - f(x)}{h}\\ &=\lim_{h\to0}\frac{f(x_1+h\hat{u_1}, x_2+h\hat{u_2}, ..., x_n+h\hat{u_n}) - f(x_1, u_2, ..., x_n)}{h} \end{aligned}$

In this formula, the symbol \({f'}_u\) stands for directional derivative and \(\hat{u_1}, \hat{u_2}, ..., \hat{u_n}\) are the components of the unit vector \(\hat{u}\) along the \(x_1, x_2, ...,x_n\) axes.

So it is the slope of the function in the direction of \(u\) (If you are unfamiliar with vectors, now would be a good time to read the first article in this series)

But how can we easily calculate this and what is more interesting (for our optimization problem), in what direction is its largest value? For this, we need so called partial derivatives.

A partial derivative of a multi variable function with respect to one of its variables is the derivative of that function to that variable with all other variables held constant. You can think of it is if we reduce the multi variable function to a single variable function and then calculate the derivative of this.

Say we have a function:

$f(x_1,x_2,...,x_i, ...,x_n)$

Then we can define partial derivatives for each variable:

$\frac{\partial f}{\partial x_1}, \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_2}, ..., \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_i} ..., \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_n}$

in which the partial derivative in \(x_i\) at a certain point \((x_1,x_2,...,x_i, ...,x_n)\) is:

$\frac{\partial f}{\partial x_i}(x_1,x_2,...,x_i, ...,x_n) = \lim_{h\to0}\frac{f(x_1,x_2,...,x_i+h, ...,x_n) - f(x_1,x_2,...,x_i, ...,x_n)}{h}$

It is the rate of change / slope of the function in the direction of \(x_i\)

Try it yourself:

the Partial Derivative

The Derivative of a Multiple Variable Function: The Gradient Vector

The gradient at a point is a vector with the direction of the greatest increase of a multi-variable function and its magnitude is the rate of increase of that function. Or, we can say that the gradient is the directional derivative in the direction of the biggest change. It is composed of the partial derivatives of the function.

$\nabla{f} = [\frac{\partial f}{\partial x_1}, \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_2}, ..., \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_i} ..., \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_n}]$

So, why is the gradient in direction of the biggest change? For this, we need to investigate the relation between the gradient and the directional derivative. We can proof the following relation between the gradient and the directional derivative (see the reference section for some proofs available on the internet):

$\begin{aligned} {f'} _u &= \nabla{f} \cdot \hat{u}\\ &=[\frac{\partial f}{\partial x_1}, \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_2}, ..., \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_i} ..., \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_n}] \cdot [\hat{u_1}, \hat{u_1}, ..., \hat{u_i}, ..., \hat{u_n}]\\ &= \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_1}\hat{u_1} + \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_1}\hat{u_1} + ... + \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_i}\hat{u_i} + ... + \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_n}\hat{u_n}\\ &= \sum_{i=1}^{n} \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_i}\hat{u_i} \end{aligned}$

So, the directional derivative along \(u\) is the dot product of the gradient with the unit vector in the direction of \(u\). Mind that this is the dot-product and thus the result is a number and not a vector!

As we know from the first article, the dot product of two vectors can be expressed through the size of the vectors and the angle between the vectors:

$\begin{aligned} \mathbf{c} &= \mathbf{a} \cdot \mathbf{b}\\ &= {\lvert\lvert{\mathbf{a}}\lvert\lvert}\text{ }{\lvert\lvert{\mathbf{b}}\lvert\lvert}\text{ }cos(\alpha)\\ \end{aligned}$

Applying this to our definition of the directional derivative above gives:

$\begin{aligned} {f'}_u &= \nabla{f} \cdot \hat{u}\\ &= {\lvert\lvert{\nabla{f}}\lvert\lvert}\text{ }{\lvert\lvert{\hat{u}}\lvert\lvert}\text{ }cos(\alpha)\\ \end{aligned}$

And because the maximum value for the cosine of an angle is 1 when the angle is 0, we know that the directional derivative will be maximized when the vector \(\hat{u}\) is in same direction as the gradient vector \(\nabla{f}\). Thus, the directional derivative is maximum in the direction of the gradient.

Also, because the size of the vector \(\hat{u}\) is 1 (we defined it as being the unit vector), you can see that the size of the gradient vector \(\nabla{f}\) is the slope of the function at that point.

The Derivative of the Derivative of the …: Second Derivative, Third Derivative, etc.

Of course, in the end, the result of differentiation is also just a function which we can also (possibly) differentiate.

For functions of a single variable, this results in the so called second derivative, third derivative, etc. For these, we use the notation:

$f''(x), f'''(x), ...$

or

$\frac{d^2f}{dx^2}, \frac{d^3f}{dx^3}$

We can do the same with functions of multiple variables.

However, because we have multiple variables, we also again have partial derivatives. Which results in partial derivatives of partial derivatives. Remember that for a function of several variables, we had a partial derivative for each variable. But those partial derivatives are also (possibly) functions of several variables, so for each partial derivative, we have multiple second partial derivatives.

Say we have a function:

$f(x_1,x_2,...,x_i, ...,x_n)$

Then we can define partial derivatives for each variable:

$\frac{\partial f}{\partial x_1}, \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_2}, ..., \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_i} ..., \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_n}$

However, each of these partial derivatives is again possibly a function of those variables:

$\begin{aligned} \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_1} &= g_1(x_1,x_2,...,x_i, ...,x_n), \\ \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_2} &= g_2(x_1,x_2,...,x_i, ...,x_n), \\ ..., \\ \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_i} &= g_i(x_1,x_2,...,x_i, ...,x_n), \\ ..., \\ \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_n} &= g_n(x_1,x_2,...,x_i, ...,x_n) \end{aligned}$

And thus for each function \(g()\), we again have the partial derivatives:

$\frac{\partial g_i}{\partial x_1}, \frac{\partial g_i}{\partial x_2}, ..., \frac{\partial g_i}{\partial x_i} ..., \frac{\partial g_i}{\partial x_n}$

And because \(g_i(x_1,x_2,...,x_i, ...,x_n) = \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_i}\)

$\frac{\partial^2 f}{{\partial x_i \partial x_1}}, \frac{\partial^2 f}{{\partial x_i \partial x_2}}, ..., \frac{\partial^2 f}{{\partial x_i \partial x_i}} ..., \frac{\partial^2 f}{{\partial x_i \partial x_n}}$

Of course, these second partial derivatives are also functions of multiple variables, so the same line of thinking applies to them.

Just as we had a (first order) directional derivative for functions with multiple variables, we also have a second order directional derivative and by extension, higher order directional derivatives.

Let us have a look at the second order directional derivative. It is the directional derivative in the direction \(u\) of the directional derivative in the direction \(u\) of the function \(f\)

Remember the definition of the directional derivative (I’ve changed the symbol for the function from \(f\) to \(g\), you’ll understand why in a second):

$\begin{aligned} {g '} _u &= \lim_{h\to0}\frac{g(x+h\hat{u}) - g(x)}{h}\\ &=\lim_{h\to0}\frac{g(x_1+h\hat{u_1}, x_2+h\hat{u_2}, ..., x_n+h\hat{u_n}) - g(x_1, u_2, ..., x_n)}{h}\\ &= \frac{\partial g}{\partial x_1}\hat{u_1} + \frac{\partial g}{\partial x_2}\hat{u_2} + ... + \frac{\partial g}{\partial x_i}\hat{u_i} + ... + \frac{\partial g}{\partial x_n}\hat{u_n}\\ \end{aligned}$

For the second directional derivative, the function \(g\) is the first directional derivative, thus:

$g = {f'}_u$

So the derivative of \(g\) is the second order derivative of \(f\), thus:

$\begin{aligned} \frac{\partial g}{\partial x_i} &= \frac{\partial {f'}_u}{\partial x_i}\\ &= \frac{\partial {f'}_u}{\partial x_i}\\ &= \frac{\partial {(\frac{\partial f}{\partial x_1}\hat{u_1} + \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_2}\hat{u_1} + ... + \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_i}\hat{u_i} + ... + \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_n}\hat{u_n}})}{\partial x_i}\\ &= \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_1\partial x_i}\hat{u_1} + \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_2\partial x_i}\hat{u_2} + ... + \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_i\partial x_i}\hat{u_i} + ... + \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_n\partial x_i}\hat{u_n}\\ &= \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_1\partial x_i}\hat{u_1} + ... + \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_n\partial x_i}\hat{u_n} \end{aligned}$

And if we plug this in the formula above:

$\begin{aligned} {g '} _u &= \frac{\partial g}{\partial x_1}\hat{u_1} ... + \frac{\partial g}{\partial x_n}\hat{u_n}\\ &= ( \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_1\partial x_1}\hat{u_1} + ... + \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_n\partial x_1}\hat{u_n})\hat{u_1} + ... + (\frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_1\partial x_n}\hat{u_1} + ... + \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_n\partial x_n}\hat{u_n})\hat{u_n}\\ &= \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_1\partial x_1}\hat{u_1}\hat{u_1} + ... + \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_n\partial x_1}\hat{u_n}\hat{u_1} + ... + \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_1\partial x_n}\hat{u_1}\hat{u_n} + ... + \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_n\partial x_n}\hat{u_n}\hat{u_n}\\ \end{aligned}$

As you can see this formula is starting to get huge. I already left off some indices but still, it is easy to get lost in all those indices. And we are only at the second directional derivative. Imagine what you would get with higher order (third, fourth, etc.) directional derivatives.

Luckily, there is a more condensed way of writing this formula but for that we need matrices.

Yes, Here Is Another word: ‘Matrices’

Definition of a Matrix

From Wikipedia:

In mathematics, a matrix (plural: matrices) is a rectangular array of numbers, symbols, or expressions, arranged in rows and columns.

In the following example, we have a matrix with 3 rows and 4 columns. We say we have a \(3 \times 4\) matrix (read as ‘3 by 4’). The number of rows and the number of columns are the so called dimensions of the matrix. Notice that we first mention the number of rows and then the number of columns.

$A = \begin{bmatrix} a_{11} & a_{12} & a_{13} & a_{14}\\ a_{21} & a_{22} & a_{23} & a_{24}\\ a_{31} & a_{32} & a_{33} & a_{34}\\ \end{bmatrix} $

Operations With Matrices

Sum and difference of two Matrices

The sum and difference of two matrices is defined by the sum or difference of each element at the same position in the matrix. Thus, say we have two matrices \(A\) and \(B\) and we want to calculate the sum \(C\), then:

$c_{ij} = a_{ij} + b_{ij}$

In which \(i\) and \(j\) are subscripts for the rows and columns.

As an example:

$A = \begin{bmatrix} a_{11} & a_{12} & a_{13} & a_{14}\\ a_{21} & a_{22} & a_{23} & a_{24}\\ a_{31} & a_{32} & a_{33} & a_{34}\\ \end{bmatrix} $

$B = \begin{bmatrix} b_{11} & b_{12} & b_{13} & b_{14}\\ b_{21} & b_{22} & b_{23} & b_{24}\\ b_{31} & b_{32} & b_{33} & b_{34}\\ \end{bmatrix} $

Then the sum is:

$\begin{aligned} C &= \begin{bmatrix} a_{11} + b_{11} & a_{12} + b_{12} & a_{13} + b_{13} & a_{14} + b_{14}\\ a_{21} + b_{21} & a_{22} + b_{22} & a_{23} + b_{23} & a_{24} + b_{24}\\ a_{31} + b_{31} & a_{32} + b_{32} & a_{33} + b_{33} & a_{34} + b_{34}\\ \end{bmatrix}\\ &= \begin{bmatrix} c_{11} & c_{12} & c_{13} & c_{14}\\ c_{21} & c_{22} & c_{23} & c_{24}\\ c_{31} & c_{32} & c_{33} & c_{34}\\ \end{bmatrix}\\ \end{aligned}$

A similar definition exists for subtraction.

This also means we can NOT add or subtract matrices with different dimensions because for some elements in one matrix, we would not have counterparts in the other matrix.

Scalar Multiplication

The scalar multiplication of a matrix with a scalar is the result of multiplying each entry in the matrix with the scalar. Thus, if we have a matrix \(A\) and a scalar \(\lambda\), then:

$c_{ij} = \lambda a_{ij}$

In which \(i\) and \(j\) are subscripts for the rows and columns.

As an example:

$A = \begin{bmatrix} a_{11} & a_{12} & a_{13} & a_{14}\\ a_{21} & a_{22} & a_{23} & a_{24}\\ a_{31} & a_{32} & a_{33} & a_{34}\\ \end{bmatrix} $

Then the scalar multiplication with \(\lambda\) is:

$\begin{aligned} C &= \begin{bmatrix} \lambda a_{11} & \lambda a_{12} & \lambda a_{13} & \lambda a_{14}\\ \lambda a_{21} & \lambda a_{22} & \lambda a_{23} & \lambda a_{24}\\ \lambda a_{31} & \lambda a_{32} & \lambda a_{33} & \lambda a_{34}\\ \end{bmatrix}\\ &= \begin{bmatrix} c_{11} & c_{12} & c_{13} & c_{14}\\ c_{21} & c_{22} & c_{23} & c_{24}\\ c_{31} & c_{32} & c_{33} & c_{34}\\ \end{bmatrix}\\ \end{aligned}$

Matrix Multiplication

Multiplication of two matrices is defined by taking the dot product of the rows of the first matrix with the columns of the second matrix. Thus, if we have a matrix \(A\) with dimensions \(m \times n\) and matrix \(B\) with dimensions \(n \times p\), then:

$c_{ij} = \sum_{k=1}^{n} a_{ik} b_{kj}$

There are some important points to take away from this definition:

- multiplication of two matrices is only possible if the number of columns in the first matrix \(A\) equals the number of rows in the second matrix \(B\) (Notice the letters used for the dimensions of the matrices when I introduced the formula).

- If we have a matrix \(A\) with dimensions \(m \times n\) and matrix \(B\) with dimensions \(n \times p\), then the dimensions of the resulting matrix of the multiplication are \(m \times p\)

- multiplication of matrices is NOT commutative. Thus \(AB \neq BA\). This can be easily seen from the definition of the multiplication below. As a matter of fact: it's even not sure if you can do the multiplication because of the requirement regarding the columns and the rows.

- multiplication of matrices is associative. Thus \(A(BC) = (AB)C\). This can be easily proven by just writing out the formula. In the references section, I also provide a link to a very understandable proof.

As an example, we have a matrix \(A\) with dimensions \(4 \times 3\).

$A = \begin{bmatrix} a_{11} & a_{12} & a_{13}\\ a_{21} & a_{22} & a_{23}\\ a_{31} & a_{32} & a_{33}\\ a_{41} & a_{42} & a_{43}\\ \end{bmatrix} $

and we have a matrix \(A\) with dimensions \(3 \times 2\)

$B = \begin{bmatrix} b_{11} & b_{12}\\ b_{21} & b_{22}\\ b_{31} & b_{32}\\ \end{bmatrix} $

Then the multiplication is:

$\begin{aligned} C &= \begin{bmatrix} a_{11} b_{11} + a_{12} b_{21} + a_{13} b_{31} & a_{11} b_{12} + a_{12} b_{22} + a_{13} b_{32} \\ a_{21} b_{11} + a_{22} b_{21} + a_{23} b_{31} & a_{21} b_{12} + a_{22} b_{22} + a_{23} b_{32} \\ a_{31} b_{11} + a_{32} b_{21} + a_{33} b_{31} & a_{31} b_{12} + a_{32} b_{22} + a_{33} b_{32} \\ a_{41} b_{11} + a_{42} b_{21} + a_{43} b_{31} & a_{41} b_{12} + a_{42} b_{22} + a_{43} b_{32} \\ \end{bmatrix}\\ &= \begin{bmatrix} c_{11} & c_{12}\\ c_{21} & c_{22}\\ c_{31} & c_{32}\\ c_{41} & c_{42}\\ \end{bmatrix}\\ \end{aligned}$

With dimensions \(4 \times 2\).

Matrix Transpose

The transpose of a matrix is the matrix obtained by converting the rows of the source matrix into columns and the columns into rows. Thus, if we have a matrix \(A\) with dimensions \(m \times n\), then:

$c_{ij} = a_{ji}$

As an example, we have a matrix \(A\) with dimensions \(4 \times 2\)

$A = \begin{bmatrix} a_{11} & a_{12}\\ a_{21} & a_{22}\\ a_{31} & a_{32}\\ a_{41} & a_{42}\\ \end{bmatrix} $

Then the transpose is:

$\begin{aligned} C &= \begin{bmatrix} a_{11} & a_{21} & a_{31} & a_{41} \\ a_{12} & a_{22} & a_{32} & a_{42} \\ \end{bmatrix}\\ &= \begin{bmatrix} c_{11} & c_{12} & c_{13} & c_{14}\\ c_{21} & c_{22} & c_{23} & c_{24}\\ \end{bmatrix}\\ \end{aligned}$

The transpose of a matrix \(A\) is noted as \(A^\top\).

A Side Note on the Transpose and the Notation of the Perceptron Integration Function

If you’ve been searching the internet on information about the perceptron, chances are you’ve found formulas for the perceptron making use of this transpose:

$w^\top x$

So why don’t we?

We’ve been using vector notation for the perceptron which makes use of the dot-product defined on vectors. However, instead of considering \(w\) and \(x\) as being vectors, we could also consider them being matrices with \(n\) rows and a single column, thus dimensions \(n \times 1\).

$\begin{aligned} w &= \begin{bmatrix} w_{11} \\ w_{12} \\ ... \\ w_n \\ \end{bmatrix}\\ x &= \begin{bmatrix} x_{11} \\ x_{12} \\ ... \\ x_n \\ \end{bmatrix}\\ \end{aligned}$

In this case, the dot-product is replaced by matrix multiplication and by definition, this multiplication is not defined for two matrices with dimensions \(n \times 1\). We can however multiply a matrix with dimensions \(1 \times n\), with a matrix with dimensions \(n \times 1\). To get at this \(1 \times n\) matrix, we take the transpose of our \(n \times 1\) matrix. Hence the formula with the transpose:

$\begin{aligned} w^\top x &= \begin{bmatrix} w_{11} & w_{12} & ... & w_n \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} x_{11} \\ x_{12} \\ ... \\ x_n \\ \end{bmatrix}\\ &= \begin{bmatrix} w_11x_11 + w_22x_22 + ... + w_nx_n \end{bmatrix} \end{aligned}$

Notice however that mathematically, the outcome of the dot product is a scalar while the outcome of matrix multiplication is another matrix. So, although the calculated value is the same, the mathematical construct is not!

So, Why Do We Need Them for the Directional Derivative?

Now that we know about matrices and matrix multiplication, let us return to the second directional derivative of a function with multiple arguments:

$\begin{aligned} {f''} _u &= \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_1\partial x_1}\hat{u_1}\hat{u_1} + ... + \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_n\partial x_1}\hat{u_n}\hat{u_1} + ... + \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_1\partial x_n}\hat{u_1}\hat{u_n} + ... + \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_n\partial x_n}\hat{u_n}\hat{u_n}\\ \end{aligned}$

Let us expand this for a function of two variables. WARNING: I’ll be using \(x\) and \(y\) instead of subscripts to \(x\), like \(x_1\) and \(x_2\) because I feel this makes things more clear: it is easier to distinguish \(x\) and \(y\) than \(x_1\) and \(x_2\). As a consequence, I’ll also use \(u_x\) and \(u_y\) instead of \(u_1\) and \(u_2\).

Thus, we have a function \(f(x, y)\). It’s second directional derivative equals to:

${f''}_u = \frac{\partial^2 f}{{\partial x}^2}\hat{u_x}^2 + \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x\partial y}\hat{u_x}\hat{u_y} + \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial y\partial x}\hat{u_y}\hat{u_x} + \frac{\partial^2 f}{{\partial y}^2}\hat{u_y}^2 $

If we expand the following matrix multiplication:

$\begin{bmatrix} \hat{u_x} & \hat{u_y} \\ \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \frac{\partial^2 f}{{\partial x}^2} & \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x\partial y} \\ \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial y\partial x} & \frac{\partial^2 f}{{\partial y}^2} \\ \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \hat{u_x} \\ \hat{u_y} \end{bmatrix} $

Expansion of the first multiplication:

$\begin{bmatrix} \hat{u_x} & \hat{u_y} \\ \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \frac{\partial^2 f}{{\partial x}^2} & \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x\partial y} \\ \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial y\partial x} & \frac{\partial^2 f}{{\partial y}^2} \end{bmatrix} $

gives:

$\begin{bmatrix} \hat{u_x} \frac{\partial^2 f}{{\partial x}^2} + \hat{u_y} \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial y\partial x} & \hat{u_x} \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x\partial y} + \hat{u_y} \frac{\partial^2 f}{{\partial y}^2} \\ \end{bmatrix} $

Then continue with the second matrix multiplication:

$\begin{aligned} \begin{bmatrix} \hat{u_x} \frac{\partial^2 f}{{\partial x}^2} + \hat{u_y} \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial y\partial x} & \hat{u_x} \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x\partial y} + \hat{u_y} \frac{\partial^2 f}{{\partial y}^2} \\ \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \hat{u_x} \\ \hat{u_y} \end{bmatrix} &= \begin{bmatrix} (\hat{u_x} \frac{\partial^2 f}{{\partial x}^2} + \hat{u_y} \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial y\partial x}) \hat{u_x} + (\hat{u_x} \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x\partial y} + \hat{u_y} \frac{\partial^2 f}{{\partial y}^2}) \hat{u_y} \end{bmatrix}\\ &= \begin{bmatrix} \hat{u_x} \frac{\partial^2 f}{{\partial x}^2} \hat{u_x} + \hat{u_y} \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial y\partial x} \hat{u_x} + \hat{u_x} \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x\partial y} \hat{u_y} + \hat{u_y} \frac{\partial^2 f}{{\partial y}^2} \hat{u_y} \\ \end{bmatrix}\\ &= \begin{bmatrix} \frac{\partial^2 f}{{\partial x}^2} \hat{u_x}^2 + \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x\partial y} \hat{u_x} \hat{u_y} + \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial y\partial x} \hat{u_y} \hat{u_x} + \frac{\partial^2 f}{{\partial y}^2} \hat{u_y}^2 \\ \end{bmatrix} \end{aligned}$

If we compare this last result with the expanded definition of the second directional derivative, we see that they are the same. So, the matrix multiplication results in the second directional derivative:

${f''}_u = \begin{bmatrix} \hat{u_x} & \hat{u_y} \\ \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \frac{\partial^2 f}{{\partial x}^2} & \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x\partial y} \\ \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial y\partial x} & \frac{\partial^2 f}{{\partial y}^2} \\ \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \hat{u_x} \\ \hat{u_y} \end{bmatrix} $

We can of course expand this again and generalize for multiple variables (using subscripts for the variables):

${f''}_u = \begin{bmatrix} \hat{u_1} & \hat{u_2} ... & \hat{u_i} & ... & \hat{u_n} \\ \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \frac{\partial^2 f}{{\partial x_1}^2} & \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_1\partial x_2} & ... & \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_1\partial x_i} & ... & \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_1\partial x_n} \\ \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_2\partial x_1} & \frac{\partial^2 f}{{\partial x_2}^2} & ... & \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_2\partial x_i} & ... & \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_2\partial x_n} \\ ... & ... & ... & ... & ... & ... \\ \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_n\partial x_1} & \frac{\partial^2 f}{{\partial x_n}{\partial x_2}} & ... & \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_n\partial x_i} & ... & \frac{\partial^2 f}{{\partial x_n}^2} \\ \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \hat{u_1} \\ \hat{u_2} \\ ... \\ \hat{u_i} \\ ... \\ \hat{u_n} \\ \end{bmatrix} $

The matrix with the partial derivatives is called the Hessian matrix H:

$H = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{\partial^2 f}{{\partial x_1}^2} & \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_1\partial x_2} & ... & \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_1\partial x_i} & ... & \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_1\partial x_n} \\ \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_2\partial x_1} & \frac{\partial^2 f}{{\partial x_2}^2} & ... & \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_2\partial x_i} & ... & \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_2\partial x_n} \\ ... & ... & ... & ... & ... & ... \\ \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_n\partial x_1} & \frac{\partial^2 f}{{\partial x_n}{\partial x_2}} & ... & \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x_n\partial x_i} & ... & \frac{\partial^2 f}{{\partial x_n}^2} \\ \end{bmatrix} $

If we now define another matrix U, having the coëfficients of the directional unit vector, as:

$U = \begin{bmatrix} \hat{u_1} \\ \hat{u_2} \\ ... \\ \hat{u_i} \\ ... \\ \hat{u_n} \\ \end{bmatrix} $

We can rewrite the second directional derivative to the terse matrix multiplication:

${f''}_u = U^\top H U$

And Some More words: Critical Points, Stationary Points and Fermats Theorem

Let us not loose track of what where we are going: we are looking for a method to find the minimum of a function.

We can find local extremums, that is, a local minimum or maximum, using Fermat’s Theorem on Stationary Points. From Wikipedia:

Fermat’s theorem is a method to find local maxima and minima of differentiable functions on open sets by showing that every local extremum of the function is a stationary point

Great, so what are these stationary points? Again from Wikipedia:

A stationary point of a differentiable function of one variable is a point on the graph of the function where the function’s derivative is zero. (…) For a differentiable function of several real variables, a stationary point is a point on the surface of the graph where all its partial derivatives are zero (equivalently, the gradient is zero).

If the derivative of a function \(f\) at a certain point is \(0\) or is not defined, then those points are called critical points. So basically, you could say that all stationary points are critical points, but not all critical points are stationary points, those where the derivative is not defined are NOT stationary points.

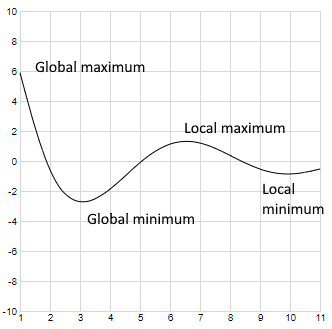

In this, a local extremum is a point where the function has either a local maximum or a local minimum. Local as opposed to Global where global meaning there is no other value for the function which is smaller/larger than the value at the global minimum/maximum and local meaning that although at this point, the function has a minimum/maximum value, there are other points where the function possibly has a smaller/larger result.

Mind however that Fermat’s theorem does not apply in the other direction: if the derivative of a function is zero at a certain point, this does not necessarily mean that we have a minimum or maximum! We can also have a so called horizontal inflection point in the case of a function of a single variable or a saddle point for functions of multiple variables.

So, how do we know we do indeed have a minimum value? We can do this with the so called Extremum test or Second Derivative test. For single variable functions, it calculates the second derivative and depending on its value a critical point is classified as being a minimum, maximum or inflection point:

- If \(f'(x) = 0\) and \(f''(x) > 0\), then the function \(f()\) has a minimum at \(x\)

- If \(f'(x) = 0\) and \(f''(x) < 0\), then the function \(f()\) has a maximum at \(x\)

- If \(f'(x) = 0\) and \(f''(x) = 0\), then we gain no extra information

To see why this works, let us get back to the meaning of derivative: the derivative of a function at a point is the slope of that function at that point. Or using another formulation: it is the rate of change of the function at that point.

This also means that if the derivative changes sign, the slope changes sign. It will be clear that a function can only change sign when its value goes though zero. If the slope changes sign, it means the function changes from going up to going down or vice versa. Which consequently means we have a maximum or minimum. So this intuîtively explains why we possibly have a minimum or maximum (or an inflection point) if the derivative is zero.

To differentiate between a maximum or a minimum, we need to check if the first derivative starts positive and turns negative or vice versa. We can do this using the second derivative which gives us the rate of change or the slope of the first derivative.

If the first derivative starts positive and turns negative, it means it is descending, which means the rate of change or the slope is negative. And thus the second derivative is negative.

Hence our rule:

- If \(f'(x) = 0\) and \(f''(x) < 0\), then the function \(f()\) has a maximum at \(x\)

Likewise, it the first derivative starts negative and becomes positive, the slope is ascending, thus the second derivative is positive, hence our rule:

- If \(f'(x) = 0\) and \(f''(x) > 0\), then the function \(f()\) has a minimum at \(x\)

However, if the first derivative, when going through zero (and thus we have a maximum or minimum of our original function), has itself a slope of zero (which means it is an inflection point), then the second derivative will at this point also become zero. On the other hand, if the first derivative, when becoming zero, has a maximum or minimum itself (it merely touches zero, but does not change sign), then the second derivative becomes zero again. But because the first derivative does NOT change sign, the differentiated function has no maximum or minimum. In short: we have a situation in which both the first and second derivative become zero but we still cannot conclude if our original function has a maximum, minimum or an inflection point at that value.

Hence the rule:

- If \(f'(x) = 0\) and \(f''(x) = 0\), then we gain no extra information

To be able to make a conclusion, we’ll need the third derivative in this case. In fact, there is a general test for this, the higher order derivative test.

Let’s define \(n>1\) and

- the \(n^{th}\) derivative of a function \(f\) at a point \(c\) is not zero

- all lower derivatives (thus \(\frac{d^{n-1}f}{dx^{n-1}}\) until \(\frac{df}{dx}\)) are zero

Then, if - n is even and the \(n^{th}\) derivative is negative; we have a local maximum at the point \(c\)

- n is even and the \(n^{th}\) derivative is positive; we have a local minimum at the point \(c\)

- n is odd and the \(n^{th}\) derivative is negative; we have an decreasing inflection point at the point \(c\)

- n is odd and the \(n^{th}\) derivative is positive; we have an increasing inflection point at the point \(c\)

Remark: If you look for information on the internet about this test, you’ll find definitions where the even and odd in the above summary are switched. The reason is that some definitions (like the one on Wikipedia) start with \(n=1\) for the second derivative. Thus, \(n\) is odd for the second derivative, which complies with the first two rules in our summary above.

Try it yourself:

Second Derivative test

For multivariable functions however, things are more complex. In that case, it is called the second partial derivative test

Remember our above discussion of the second derivative test for functions of a single variable: in it, we deduced that if the first derivative is zero for a function, then we need to evaluate the second derivative to differentiate between a minimum and maximum value. If the second derivative is negative, we have a maximum, if positive we have a minimum.

We can make a similar assertion here.

We have shown that the maximum slope for a multivariable function is in the direction of the gradient. So, if the maximum slope is zero, then the directional derivative will be zero in all directions. Because the maximum slope is the gradient, for the maximum slope to be zero, the gradient must be zero and thus all partial derivatives must be zero.

How can we now differentiate between a maximum, minimum and saddle point? A similar line of thinking as for he single variable function can be made,

For the point where the gradient is zero to be a minimum or maximum, we must have that the directional derivative changes sign in all directions, or, the directional derivative must continue ascending or descending in al directions. Which means the second directional derivative must be either positive or negative.

Mathematically:

- If the gradient is zero, then we have a minimum if \({f''}_u = U^\top H U \gt 0\)

- If the gradient is zero, then we have a maximum if \({f''}_u = U^\top H U \lt 0\)

It just so happens that the inequalities above have a name:

- The definition of Positive Definite is \(A^\top H A \gt 0\)

- The definition of Negative Definite is \(A^\top H A \lt 0\)

In both inequalities, the matrix \(A\) can be any matrix with a single column. Our matrices \(U\) however represent the unit vector, but we can see that this is the same as \(A\) with a scale factor, or \(A\) multiplied by a scalar:

$A = \lambda U$

And thus:

$\begin{aligned} A^\top H A &= \lambda U^\top H \lambda U\\ &= {\lambda}^2 U^\top H U\\ \end{aligned}$

And because \({\lambda}^2 \gt 0\), the inequalities written with matrix A are the same as written with matrix U.

And we can conclude that:

- If the Hessian of a function is positive definite we have a minimum

- If the Hessian of a function is negative definite we have a maximum

Optimizing (minimizing) the Mean Squared Errors

So, let us see where we are now:

- We have defined a cost function to be able to determine a best fit (according to this cost function).

- We know our chosen cost function is convex (we’ll prove it in a minute) and thus has a single minimal value.

- We can determine where this single minimal value is by differentiating our cost function and determine where the derivative is 0.

Getting the Derivative of Our Cost Function

The derivative of a function is always taken to the variables of this function. If we take a look at out cost function:

$E(w) = \frac{1}{2} \sum_{j=1}^{M} e_j^2$

In this:

- M is the number of samples

- j is the index of the sample

and with:

$\begin{aligned} e &= d-\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x}\\ \end{aligned}$

we have:

$E(w) = \frac{1}{2} \sum_{j=1}^{M} (d-\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x})_j^2$

in which:

- \(d\) is the desired outcome

- \(w\) is the weights of the perceptron

- \(x\) is the input (the features) to the perceptron.

You might be tempted to think that we need to differentiate to \(x\) but that is wrong. We want to find, given some data pairs (desired outcome, observed features), thus \((d, x)\), for which values \(w\) the total error is minimal. This means \(w\) is our variable, our unknown, and \(d\) and \(x\) are values which are given and which we plug into the error function. Thus, we differentiate with respect to \(w\).

But \(w\) is a vector which means the error function is a multiple variable function. So we will need to take the partial derivatives with respect to each \(w_i\) in our vector \(w\).

There are a few rules which govern the calculation of the derivative of a function, like the power rule, multiplication by a constant, summary, difference, chaining, etc. We will not discuss all the rules, but only those we need in our cost function.

If you’re interested, you can have a look in the references section for some other rules.

If we take our cost function, then we can see we will need the power rule for the quadratic term, the constant rule for the division by \(2\), the summary and difference rule for the \(\sum\) terms and the calculation of the error itself (\(e = d-\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x}\)) and finally the chain rule for putting them all together.

Let us see what these rules tell and apply them to our cost function:

Keep attention to the indices because things are going to get real messy.

The multiplication by constant rule:

$f(x) = n g(x)$

Then it can be proven that:

$\begin{aligned} \frac{df(x)}{dx} &= \frac{d(ng(x))}{dx} \\ &= n\frac{dg(x)}{dx} \end{aligned}$

Applied to our cost function:

$E(w) = \frac{1}{2} \sum_{j=1}^{M} {(d-\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x})}_j^2$

If we take the partial derivative with respect to the dimension \(k\):

$\begin{aligned} \frac{\partial E}{\partial w_k} &= \frac{\partial {\frac{1}{2} \sum_{j=1}^{M} {(d-\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x})}_j^2}}{\partial w_k} \\ &= \frac{1}{2} \frac{\partial {\sum_{j=1}^{M} {(d-\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x})}_j^2}}{\partial w_k} \end{aligned}$

Next is the summary rule:

$f(x) = g_1(x) + g_2(x)$

Then it can be proven that:

$\begin{aligned} \frac{df(x)}{dx} &= \frac{d( g_1(x) + g_2(x))}{dx} \\ &= \frac{dg_1(x)}{dx} + \frac{dg_2(x)}{dx} \end{aligned}$

Further application to our cost function for the \(\sum_{j=1}^{M}\) term :

$\begin{aligned} \frac{\partial E}{\partial w_k} &= \frac{1}{2} \frac{\partial {\sum_{j=1}^{M} {(d-\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x})}_j^2}}{\partial w_k} \\ &= \frac{1}{2} \sum_{j=1}^{M} \frac{\partial { ({(d-\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x})}_j^2})}{\partial w_k} \end{aligned}$

Next is the chain rule which handles functions whose arguments are also functions.

Let's say we have two functions:

$\begin{aligned} y &= g(z)\\ z &= h(x) \end{aligned}$

Then we can combine them into a single function as :

$\begin{aligned} y &= g(h(x))\\ &= f(z) \end{aligned}$

Then it can be proven that:

$\begin{aligned} \frac{df(x)}{dx} &= \frac{d(g(h(x)))}{dx} \\ &= \frac{dg(h(x))}{dx} \frac{dh(x)}{dx} \end{aligned}$

And the power rule:

$f(x) = x^n$

Then it can be proven that:

$\begin{aligned} \frac{df(x)}{dx} &= \frac{d(x^n)}{dx} \\ &= nx^{(n-1)} \end{aligned}$

If we combine the power rule applied to a function and the chain rule, we get

$f(x) = g(x)^n$

Then:

$\begin{aligned} \frac{df(x)}{dx} &= \frac{d(g(x)^n)}{dx} \\ &= ng(x)^{(n-1)}\frac{dg(x)}{dx} \end{aligned}$

Further application to our cost function for the \(\frac{\partial { ({(d-\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x})}^2})}{\partial w_i}\) term :

$\begin{aligned} \frac{\partial E}{\partial w_k} &= \frac{1}{2} \sum_{j=1}^{M} \frac{\partial { ({(d-\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x})}_j^2})}{\partial w_k} \\ &= \frac{1}{2} \sum_{j=1}^{M} 2 (d-\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x})_j \frac{\partial { {(d-\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x})_j}}}{\partial w_k} \\ &= \sum_{j=1}^{M} (d-\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x})_j \frac{\partial { {(d-\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x})_j}}}{\partial w_k} \\ \end{aligned}$

Now you also know why we divided by \(2\): it makes the coëfficient of the square disappear after derivation.

Before we continue, remember that the term \((d-\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x})_j\) is the error of sample \(j\):

$(d-\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x})_j = e_j$

And \(\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x}\) is the dot product and thus also a summation:

$\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x} = \sum_{i=1}^{N} w_ix_i$

In this:

- \(N\) is the dimension of our feature vector.

And thus, the partial derivative of the error function, which is a function of the weights, and with respect to the dimension \(k\) is:

$\begin{aligned} \frac{\partial E}{\partial w_k} &= \sum_{j=1}^{M} e_j \frac{\partial { {(d-\sum_{i=1}^{N} w_ix_i)_j}}}{\partial w_k} \\ \end{aligned}$

In this:

- \(k\) is the dimension in which we take the partial derivative

- \(M\) is the number of samples

- \(j\) is the index of the sample

- \(i\) is the index of the dimension of a sample

In words:

- The partial derivative of the errorfunction with respect to the dimension \(k\) is

- the sum over all samples \(j\) of

- the error of the sample

- times the partial derivative of the error with respect to dimension \(k\) of sample \(j\)

It will be clear that the derivative of a constant is zero: a constant does not change.

In our error function \(d\) is a constant, so its derivative is \(0\). But because we take the partial derivatives each \(w_k\) is also a constant with respect to \(w_i\) if \(i\neq k\), so applying this knowledge and making use of the summary rule and expanding the summary resulting from the dot product we get:

$\begin{aligned} \frac{\partial E}{\partial w_k} &= \sum_{j=1}^{M} e_j \frac{\partial { {(d-\sum_{i=1}^{N} w_ix_i)_j}}}{\partial w_k} \\ &= - \sum_{j=1}^{M} e_j \frac{\partial {({\sum_{i=1}^{N} w_ix_i)_j}}}{\partial w_k} \\ &= - \sum_{j=1}^{M} e_j (\frac{\partial {(w_1x_1 + ... + w_ix_i + ... + w_nx_n)_j}}{\partial w_k} )\\ &= -( e_1 (\frac{\partial {(w_1x_1 + ... + w_ix_i + ... + w_nx_n)_1}}{\partial w_k}) + ... + e_j (\frac{\partial {(w_1x_1 + ... + w_ix_i + ... + w_nx_n)_j}}{\partial w_k}) + ... + e_m (\frac{\partial {(w_1x_1 + ... + w_ix_i + ... + w_nx_n)_m}}{\partial w_k}))\\ \end{aligned}$

Of the above terms, only the ones with \(i=k\) remain: for the others the term \(wx\) is considered constant with respect to derivation to \(\partial w\) and thus are \(0\)

$\begin{aligned} \frac{\partial E}{\partial w_k} &= -( e_1 {x_k}_1 + .. + e_j {x_k}_j + ... + e_m {x_k}_m)\\ &= - \sum_{j=1}^M {e_j {x_k}_j} \end{aligned}$

Thus, it is the sum over all samples of the error of each sample times its feature value of the k-th dimension.

Proving Convexity

Remember from our discussion on the second partial derivative test, we concluded that a function is convex if the Hessian matix of the function is positive semidefinite. Also remember that the Hessian matrix was formed by arranging all the second partial derivatives of the function in a certain order in a matrix.

So, to proof the positive semidefiniteness of the Hessian, we’ll need the second partial derivatives.

Above, we calculated the first partial derivatives:

$\begin{aligned} \frac{\partial E}{\partial w_k} &= - \sum_{j=1}^M {e_j {x_k}_j} \\ &= - \sum_{j=1}^M {(d-\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x})_j {x_k}_j} \end{aligned}$

From this, we can calculate the second order partial derivatives:

$\begin{aligned} \frac{\partial E}{{\partial w_k}{\partial w_l}} &= \frac{\partial{(- \sum_{j=1}^M {{(d-\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x})_j x_k}_j}})}{\partial w_l} \\ &= - \sum_{j=1}^M {{x_k}_j \frac{\partial{(d-\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x})_j }}{\partial w_l} } \end{aligned}$

Again, the term \(\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x}\) is a dot product and thus also a sum:

$\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x} = \sum_{i=1}^{N} w_ix_i$

Also, \(d\) is a constant: it’s derivative is \(0\), and thus:

$\begin{aligned} \frac{\partial E}{{\partial w_k}{\partial w_l}} &= - \sum_{j=1}^M {{x_k}_j \frac{\partial{(-\sum_{i=1}^{N} w_ix_i)_j }}{\partial w_l} } \\ &= \sum_{j=1}^M {{x_k}_j \frac{\partial{(w_1x_1 + ... + w_ix_i + ... + w_Nx_N)_j }}{\partial w_l} } \end{aligned}$

As before, of the above only the \(i = l\) terms remain as the others are constant with respect to the partial derivative. Thus:

$\begin{aligned} \frac{\partial E}{{\partial w_k}{\partial w_l}} &= - \sum_{j=1}^M {{x_k}_j {x_l}_j } \\ &= \sum_{j=1}^M {({x_k} {x_l})_j} \end{aligned}$

Finally, the Hessian matrix is:

$\begin{aligned} H &= \begin{bmatrix} \sum_{j=1}^M {({x_1} {x_1})_j} & ... & \sum_{j=1}^M {({x_1} {x_i})_j} & ... & \sum_{j=1}^M {({x_1} {x_N})_j} \\ ... & ... & ... & ... & ... \\ \sum_{j=1}^M {({x_i} {x_1})_j} & ... & \sum_{j=1}^M {({x_i} {x_i})_j} & ... & \sum_{j=1}^M {({x_i} {x_N})_j} \\ ... & ... & ... & ... & ... \\ \sum_{j=1}^M {({x_N} {x_1})_j} & ... & \sum_{j=1}^M {({x_N} {x_i})_j} & ... & \sum_{j=1}^M {({x_N} {x_N})_j} \\ \end{bmatrix} \\ &= \sum_{j=1}^M( \begin{bmatrix} {x_1} {x_1} & ... & {x_1} {x_i} & ... & {x_1} {x_N} \\ ... & ... & ... & ... & ... \\ {x_i} {x_1} & ... & {x_i} {x_i} & ... & {x_i} {x_N} \\ ... & ... & ... & ... & ... \\ {x_N} {x_1} & ... & {x_N} {x_i} & ... & {x_N} {x_N} \\ \end{bmatrix}) \end{aligned} $

So, we have \(M\) times the matrix:

$\begin{bmatrix} {x_1} {x_1} & ... & {x_1} {x_i} & ... & {x_1} {x_N} \\ ... & ... & ... & ... & ... \\ {x_i} {x_1} & ... & {x_i} {x_i} & ... & {x_i} {x_N} \\ ... & ... & ... & ... & ... \\ {x_N} {x_1} & ... & {x_N} {x_i} & ... & {x_N} {x_N} \\ \end{bmatrix} $

We can split this matrix as being the multiplication of following column and row matrices:

$\begin{bmatrix} {x_1} \\ ... \\ {x_i} \\ ... \\ {x_N} \\ \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} {x_1} & ... & {x_i} & ... & {x_N} \end{bmatrix} $

Now, recap the definition of positive semi definiteness:

$A^\top H A \gt 0$

In this, \(A\) is a column matrix and thus we can rewrite this (by substituting with the above expression for the Hessian):

$\begin{bmatrix} {a_1} & ... & {a_i} & ... & {a_N} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} {x_1} \\ ... \\ {x_i} \\ ... \\ {x_N} \\ \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} {x_1} & ... & {x_i} & ... & {x_N} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} {a_1} \\ ... \\ {a_i} \\ ... \\ {a_N} \\ \end{bmatrix} \gt 0 $

Because of the associativity of the matrix multiplication, we can write:

$\begin{bmatrix} {a_1}{x_1} + ... + {a_i}{x_i} + ... + {a_N}{x_N} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} {x_1}{a_1} + ... + {x_i}{a_i} + ... + {x_N}{a_N} \end{bmatrix} $

Basically, this is the multiplication of two scalars. And because of the commutativity of scalar multiplication:

$\begin{bmatrix} {a_1}{x_1} + ... + {a_i}{x_i} + ... + {a_N}{x_N} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} {a_1}{x_1} + ... + {a_i}{x_i} + ... + {a_N}{x_N} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} {a_1}{x_1} + ... + {a_i}{x_i} + ... + {a_N}{x_N} \end{bmatrix}^2 $

So, we have the square of a scalar, which is always positive. And we can conclude that the result must be larger than or equal to \(0\), thus the Hessian is positive semi definite, thus our cost function is convex.

Solving the Problem

So, now we know the errorfunction is convex, and thus has a single global minimum. If we can find where the derivative is zero, we have found the optimal solution for our perceptron.

There are two ways to search the minimum of the cost function.

A first solution is to solve for the derivative being zero. So we calculate the derivative, set it to zero and then solve this equation. This also gives an exact solution. We will not discuss this solution any further here. This solution can only be used on our very simple perceptron and does not generalize to multi perceptron neural networks. And even for a single perceptron, if we have a lot of properties which define our two target classes (thus \(N\) is large), due to the complexity of the calculations for finding this result, it is computationally not a viable solution.

A second solution is called gradient descend: we calculate the gradient at some random point to find the direction in which the function is getting closer to its minimum: it is descending. Then we take a small step in that direction and start over again. We do this until the change of the outcome of the function is below a pre-defined threshold.

Gradient Descent

Gradient Descend in Words (And Pictures)

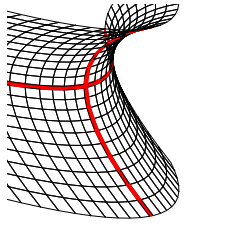

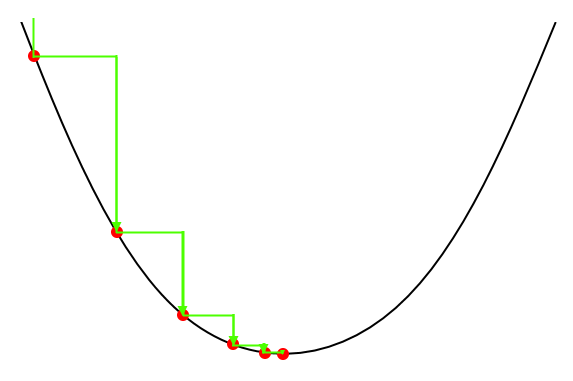

The key idea behind gradient descend is that, starting from some random point on the curve of our cost function, we would like to move into the direction of the minimum until we reach this minimum.

Graphically, we would like to do the following:

We would like to “step” to the minimum by descending on the curve. We can do this by moving into the direction of the slope if it is descending or move in the opposite direction of the slope if it is ascending.

So, in gradient descent, the gradient is used to determine the direction into which we want to move.

Let’s say we have a function in a single variable \(f(x)\).

If we are on the descending side of the function, we want to move (take a step) in the direction of increasing x, thus:

If we represent our step by the symbol \(\Delta x\)

$x_t = x + \Delta x > x$

If we are on the ascending side, we want to move in the direction of decreasing x:

$x_t = x - \Delta x < x$

If we now choose \(\Delta x\) to be proportional to the slope (remember the slope is equal to the derivative \(\frac{df(x)}{dx}\) ), we have:

$\Delta x = \lambda \frac{df(x)}{dx} $

With the slope being negative on the descending side, we get (remember that a negative number multiplied by a negative number is positive):

$x_t = x - \lambda \frac{df(x)}{dx} > x$

With the slope being positive on the ascending side, we get:

$x_t = x - \lambda \frac{df(x)}{dx} < x$

In general, we can take steps proportional to the negative value of the slope. Or, we take steps against the direction of the slope.

A similar line of thinking can be followed for functions of multiple variables, but then we have a directional derivative equal to the slope in a certain direction. As we have seen, the directional derivative has its largest value in the direction of the gradient, so this is the direction we will follow. Thus we get:

$x_t = x - \lambda \nabla{f}$

in which \(x_t\), \(x\) and \(\nabla{f}\) are vectors

But It Can Go Wrong

It can be proven that for the correct preconditions, the gradient descent algorithm always converges to a (local) minimum. However, if those conditions are not met, then convergence is not guaranteed.

One such condition has to do with the size of \(\lambda\). If \(\lambda\) is too big then overshoot can happen and the algorithm can oscillate around the optimal solution.

Try it yourself:

Gradient Descend

The ADALINE Learning Rule

The ADALINE learning rule can be written as:

$\mathbf{w}_{i+1} = \mathbf{w}_{i} + \lambda \sum_{j=1}^M (d-o)_j\mathbf{x_j}$

in which \((d - o)\) is the error \(e\), so

$\mathbf{w}_{i+1} = \mathbf{w}_{i} + \lambda \sum_{j=1}^M e_j \mathbf{x_j}$

Remember that \(\mathbf{w}\) is a vector representing the weights applied to each feature of our featurevector \(\mathbf{x}\), so what we really have here is (writing vectors in column notation):

$\begin{bmatrix} {{w_1}_{i+1}} \\ ... \\ {{w_i}_{i+1}} \\ ... \\ {{w_N}_{i+1}} \\ \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} {{w_1}_{i}} \\ ... \\ {{w_i}_{i}} \\ ... \\ {{w_N}_{i}} \\ \end{bmatrix} + \lambda \begin{bmatrix} \sum_{j=1}^M e_j {{x_1}_j} \\ ... \\ \sum_{j=1}^M e_j {{x_i}_j} \\ ... \\ \sum_{j=1}^M e_j {{x_N}_j} \\ \end{bmatrix} $

Let us look back at the gradient of the errorfunction:

$\frac{\partial E}{\partial w_k} = \sum_{j=1}^M {{e_j x_k}_j}$

Also, we found following gradient descent rule to find the minimum of a function \(f(w)\):

$\mathbf{w_{i+1}} = \mathbf{w_i} - \lambda \nabla{f}$

In this, \(\nabla{f}\) stands for the vector of all partial derivatives of \(f\):

$\nabla{f} = \begin{bmatrix} \sum_{j=1}^M {{e_j x_1}_j} \\ ... \\ \sum_{j=1}^M {{e_j x_i}_j} \\ ... \\ \sum_{j=1}^M {{e_j x_N}_j} \\ \end{bmatrix}$

Substituting the gradient of the errorfunction in the gradient descent rule and taking into account that \(\mathbf{w_{i+1}}\) and \(\mathbf{w_i}\) are actually vector gives us:

$\begin{bmatrix} {{w_1}_{i+1}} \\ ... \\ {{w_i}_{i+1}} \\ ... \\ {{w_N}_{i+1}} \\ \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} {{w_1}_{i}} \\ ... \\ {{w_i}_{i}} \\ ... \\ {{w_N}_{i}} \\ \end{bmatrix} + \lambda \begin{bmatrix} \sum_{j=1}^M e_j {{x_1}_j} \\ ... \\ \sum_{j=1}^M e_j {{x_i}_j} \\ ... \\ \sum_{j=1}^M e_j {{x_N}_j} \\ \end{bmatrix} $

Tadaaa: we get our learning rule. So, the ADALINE learning rule is gradient descent on the least squares error function !!!

Notice how we use the sum of the error of all the samples. This is in contrast with the learning rule for the Rosenblatt perceptron which used the error of a single sample. We call this batch learning.

Wrap Up

The basic formula classifies the features by weighting them into two separate classes.

We have seen that the way this is done, is by comparing the dot product of the feature vector \(\mathbf{x}\) and the weight vector \(\mathbf{w}\) with some fixed value \(b\). If the dot product is larger then this fixed value, then we classify them info one class by assigning them a label 1, otherwise we put them into the other class by assigning them a label -1.

$f(x) = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } w_1x_1 + w_2x_2 + ... + w_ix_i + ... + w_nx_n > b\\ -1 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} $

Behaviour of the ADALINE Perceptron

Because the formula of the perceptron is basically a hyperplane, we can only classify things into two classes which are linearly separable. A first class with things above the hyper-plane and a second class with things below the hyper-plane.

However, the difference with the Rosenblatt perceptron is that during learning we can get an optimal solution although our training samples may not be linearly separable, a thing not possible during learning of a Rosenblatt perceptron.

We’ve again covered a lot of ground here, but without using a lot of the lingo surrounding perceptrons, neural networks and machine learning in general. There was already enough lingo with the mathematics that I didn’t want to bother you with even more definitions.

In the article on the Rosenblatt Perceptron, we already saw a few definitions, and here are some more:

Objective Function

An objective function is a function used to evaluate the performance of a solution to an optimization problem. In the context of our perceptron, it is the function used to evaluate a candidate weight vector.

Loss Function

Where an objective function makes no assumption on how we optimize, that is if we use maximization, minimization or anything else, a loss function makes the assumption that we minimize our objective function. Because we want to minimize, a good loss function generally gives small values for good results and large values for bad results.

Cost Function

The name cost function is in general synonymous with loss function.

Error Function

The error function can be seen as the cost function for a single training example.

L1 and L2 Loss

Remember from our discussion on the squared errors and the possibility of just using the absolute value of the difference? The absolute value of the error is called the L1 loss and the square value is called the L2 loss.

Batch Learning vs Online Learning

If we use all the samples at once to find the optimal solution, we speak of batch learning: we use a batch of samples to optimize our cost function. This is in contrast with the Rosenblatt perceptron for which we recalculated the weights after each new sample. In the latter case, we speak of online learning.

What is Wrong with the ADALINE Perceptron?

Although the ADALINE perceptron is an improvement on the Rosenblatt perceptron with respect to its learning procedure, with respect to its classification capabilities we did not gain anything: we still can only classify two classes of things.

In order to be able to classify more classes, we need more perceptrons linked together: neural networks.

Which is the subject of the next article…

References

Sum of Squared Errors

About the various calculation of squares of somethings:

About why to use the Mean squared Sum of Errors:

If you want a deeper dive into why we use the squares sum of errors instead of the summation of the absolute values, following are good reads:

On convex optimization (which is a whole subfield on its own):

Maxima, Minima and the Slope

Wikipedia on maxima and minima:

Wikipedia on the slope:

Another deep dive into the slope of a function

Limit, Continuity and Differentiability

About Limits:

Proving the limit using the epsilon delta definition (which is not the same as calculating the limit using the epsilon delta definition):

What does it mean if we say “becomes infinite”?

A mathematical reasoning as to why, if the denominator is zero, then the nominator must be zero to have a finite result:

About Differentiability and the Derivative:

Following contains a mathematical rigorous proof as to why continuity is needed for differentiability:

Some clarification on the proof:

A different take on the proof using the ϵ−δ definition:

About partial derivatives:

More on Directional Derivatives:

About the gradient

Following is a very understandable proof of the relation between the Directional Derivative and the Gradient: Directional Derivatives

It does however make use of the so called chain rule which I have not handled yet, but you can read about it here: Chain rule

A similar proof but less detailed can be found in Derivation of the directional derivative and the gradient and Math 20C Multivariable Calculus - Lecture 16

More rules for calculating the derivative: Derivatives rules

Matrices

Wikipedia on matrices: Matrix

Why the strange way of defining multiplication? If has to do with linear transformations:

Critical Points, Stationary Points and Fermat’s Theorem

More about stationary points: what is the difference between stationary point and critical point in calculus?

If you want to dig deeper into what the Hessian matrix is:

Proof of Fermat’s theorem:

Two different ways of proving the statement:

More on the second derivative test and the higher order derivative test:

Proving convexity of linear least squares:

Gradient Descent

An article with what I consider a correct illustration of gradient descent: A way to improve gradient descent stochastic gradient descent with restarts

Another take on why subtraction is the correct operation for the update:

Learning with gradient descent

It can be proven that gradient descent, under some conditions, is guaranteed to converge to the minimum. See following references:

ADALINE

Wikipedia on ADALINE: ADALINE

ADALINE seen from the standpoint of signal processing: Adaline and Madaline

History

- 20th August, 2020: Initial version