Let’s dive into it and try to understand what io_uring is and what problems it solves. And then we will construct a small demo application with Go to play with it.

In Linux, system calls (syscalls) are at the heart of everything. They are the primary interface through which an application interacts with the kernel. Therefore, it is vital that they are fast. And especially in a post-Spectre/Meltdown world, this is all the more important.

A major chunk of the syscalls deal with I/O, because that’s what most applications do. For network I/O, we’ve had the epoll family of syscalls which have provided us with reasonably fast performance. But in the filesystem I/O department, things were a bit lacking. We’ve had async_io for a while now, but apart from a small niche set of applications, it isn’t very beneficial. The major reason being that it only works if the file is opened with the O_DIRECT flag. This will make the kernel bypass any OS caches and try to read and write from and to the device directly. It’s not a very good way to do I/O when we are trying to make things go fast. And in buffered mode, it would behave synchronously.

All that is changing slowly because now we have a brand new interface to perform I/O with the kernel: io_uring.

There’s a lot of buzz happening around it. And rightly so, because it gives us an entirely new model to interact with the kernel. Let’s dive into it and try to understand what it is and how it solves the problem. And then we will construct a small demo application with Go to play with it.

Background

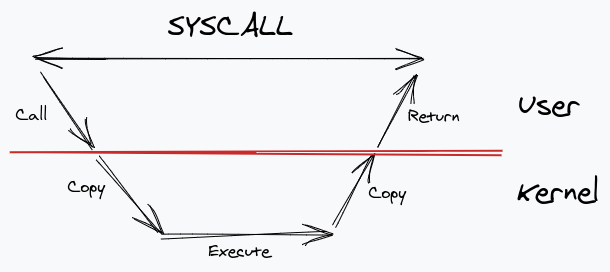

Let’s take a step back and think of how usual syscalls work. We make a syscall, our application in the user layer calls into the kernel and makes a copy of the data in kernel space. After the kernel is done with the execution, it copies the result back to user-space buffers. And then it returns. All of this happens while the syscall remains blocked.

Right off the bat, we can see a lot of bottlenecks. There’s lots of copying going around, and there’s blocking. Go handles this problem by bringing another layer between the application and the kernel: the runtime. It uses a virtual entity (commonly referred to as P) which contains a queue of goroutines to run, which is then mapped to OS threads.

This level of indirection allows it to do some interesting optimizations. Whenever we make a blocking syscall, the runtime is aware of it, and it detaches the thread from the P executing the goroutine, and acquires a new thread to execute other goroutines. This is known as a hand-off. And when the syscall returns, the runtime tries to reattach it to a P. If it cannot get a free P, it just pushes the goroutine to a queue to be executed later and stores the thread in a pool. This is how Go gives the appearance of “non-blocking”-ness when your code enters a system call.

This is great but it still does not solve the main problem, which is that copies still happen and the actual syscall still blocks.

Let’s think of the first problem at hand: copies. How do we prevent copies happening from user-space to kernel-space? Well, obviously we need some sort of shared memory. Okay, that can be done using the mmap system call which can map a chunk of memory that is shared between the user and kernel.

That takes care of copying. But what about synchronization? Even if we don’t copy, we need some way to synchronize data access between us and the kernel. Otherwise we encounter the same problem because the application would need to make a syscall again to perform the locking.

If we look at the problem as the user and kernel being two separate components talking with each other, it is essentially a producer-consumer problem. The user creates syscall requests, the kernel accepts them. And once it’s done, it signals the user that it’s ready, and the user accepts them.

Fortunately, there’s an age-old solution to this problem: ring buffers. A ring buffer allows efficient synchronization between producers and consumers with no locking at all. And as you might have already figured out, we need two ring buffers: a submission queue (SQ), where the user acts as the producer and pushes syscall requests, and the kernel consumes them, and a completion queue (CQ), where the kernel is the producer pushing completion results, and the user consumes them.

With such a model, we have eliminated any memory copies and locks entirely. All communication from user to kernel can happen very efficiently. And this is essentially the core idea that io_uring implements. Let’s briefly dive into its internals and see how it is actually implemented.

Introduction to io_uring

To push a request to the SQ, we need to create a Submission Queue Entry (SQE). Let’s assume that we want to read a file. Skimming over a lot of details, an SQE will basically contain:

- Opcode: An operation code which describes the syscall to be made. Since we are interested in reading a file, we will use the

readv system call which maps to the opcode IORING_OP_READV. - Flags: These are modifiers which can be passed with any request. We will get to it in a moment.

- Fd: The file descriptor of the file that we want to read.

- Address: For our

readv call, it creates an array of buffers (or vectors) to read the data into. Therefore, the address field contains the address of that array. - Length: The length of our vector array.

- User data: An identifier to associate our request when it comes out of the completion queue. Keep in mind that there is no guarantee that the completion results will come out in the same order as SQEs. That would defeat the whole purpose of having an async API. Therefore, we need something to identify the request we made. This serves that purpose. Usually this is a pointer to some struct holding data that has metadata of the request.

On the completion side, we get a Completion Queue Event (CQE) from the CQ. This is a very simple struct which contains:

- Result: The return value from the

readv syscall. If it succeeded, it will have the number of bytes read; otherwise, it will have an error code. - User data: The identifier that we had passed in the SQE.

There’s just one important detail to note here: both the SQ and CQ are shared between the user and the kernel. But whereas the CQ actually contains the CQEs, for SQ it’s a bit different. It is essentially a layer of indirection wherein the value of an index in the SQ array actually contains the index of the real array holding the SQE items. This is useful for certain applications which have submission requests inside internal structures, and therefore allows them to submit multiple requests in one operation, essentially easing the adoption of the io_uring API.

This means we actually have three things mapped in memory: the submission queue, the completion queue, and the submission queue array. The following diagram should make things clear:

Now let’s revisit the flags field that we skipped over earlier. As we discussed, CQE entries can come completely out of order from what they were submitted in the queue. This brings up an interesting problem. What if we wanted to perform a sequence of I/O operations one after the other? For example, a file copy. We would want to read from a file descriptor and write to another. With the current state of things, we cannot even start to submit the write operation until we see the read event appear in the CQ. That’s where the flags come in.

We can set IOSQE_IO_LINK in the flags field to achieve this. If this is set, the next SQE gets automatically linked to this one, and it won’t start until the current SQE is completed. This allows us to enforce ordering on I/O events the way we want. File copying was just one example. In theory, we can link any syscall one after another, until we push an SQE where the field is not set, at which point, the chain is considered broken.

The system calls

With this brief overview of how io_uring operates, let’s look into the actual system calls that make it happen. There are just two of them.

int io_uring_setup(unsigned entries, struct io_uring_params *params);

The entries denote the number of SQEs for this ring. params is a struct that contains various details regarding the CQ and the SQ that are to be used by the application. It returns a file descriptor to this io_uring instance.

int io_uring_enter(unsigned int fd, unsigned int to_submit, unsigned int min_complete, unsigned int flags, sigset_t sig);

This call is used to submit requests to the kernel. Let’s quickly go through the important ones:

fd is the file descriptor of the ring returned from the previous call.to_submit tells the kernel how many entries to consume from the ring. Remember that the rings are in shared memory. So, we are free to push as many entries as we want before asking the kernel to process them.min_complete indicates how many entries that the call should wait for to complete before returning.

The astute reader would notice that having to_submit and min_complete in the same call means that we can use it to do either only submission, or only completion, or even both! This opens up the API to be used in various interesting ways depending on the application workload.

Polled mode

For latency-sensitive applications or ones with extremely high IOPS, letting the device driver interrupt the kernel every time data is available to be read is not efficient enough. If we have a lot of data to be read, a high rate of interrupts would actually slow down the kernel throughput for processing the events. In those situations, we actually fall back to polling the device driver. To use polling with io_uring, we can set the IORING_SETUP_IOPOLL flag in the io_uring_setup call and keep polling events with the IORING_ENTER_GETEVENTS set in the io_uring_enter call.

But this still requires us, the user, to make the calls. To take things up even a notch higher, io_uring also has a feature called “kernel-side polling” whereby if we set the IORING_SETUP_SQPOLL flag in io_uring_params, the kernel will poll the SQ automatically to check for new entries and consume them. This essentially means that we can keep doing all the I/O we want without performing even a single. system. call. This changes everything.

But all of this flexibility and raw power comes at a cost. Using this API directly is non-trivial and error-prone. Since our data structures are shared between user and kernel, we need to setup memory barriers (magical compiler incantations to enforce ordering of memory operations) and other nitty-gritties to get things done properly.

Fortunately, Jens Axboe, the creator of io_uring has created a wrapper library called liburing to help simplify all of this. With liburing, we roughly have to do this set of steps:

io_uring_queue_(init|exit) to set up and tear down the ring.io_uring_get_sqe to get an SQE.io_uring_prep_(readv|writev|other) to mark which syscall to use.io_uring_sqe_set_data to mark the user data field.io_uring_(wait|peek)_cqe to either wait for CQE or peek for it without waiting.io_uring_cqe_get_data to get back the user data field.io_uring_cqe_seen to mark the CQE as done.

Wrapping io_uring in Go

This was a lot of theory to digest. There’s even more of it which I have deliberately skipped for the sake of brevity. Now, let’s get back to writing some code in Go and take this for a spin.

For simplicity and safety we will use the liburing library, which means we will need to use CGo. That’s fine because this is just a toy, and the right way would be have native support in the Go runtime. As a result of that, we will unfortunately have to use callbacks. In native Go, the running goroutine would be put to sleep by the runtime and then woken up when the data would be available in the completion queue.

Let’s name our package frodo (and just like that I have knocked out one of the two hardest problems in computer science). We will just have a very simple API to read and write files. And two more functions to setup and cleanup the ring when done.

Our main workhorse will be a single goroutine which takes in submission requests and pushes them to the SQ. And from C we will make a callback to Go with the CQE entry. We will use the fd of the files to know which callback to execute once we get our data. However, we also need to decide when to actually submit the queue to the kernel. We maintain a queue threshold, where if we exceed a threshold of pending requests, we submit. And also, we expose another function to the user to allow them to make the submission by themselves to allow them to have better control over application behavior.

Note that, once again, this is an inefficient way of doing things. Since the CQ and SQ are completely separate, they don’t need any sort of locking at all, and therefore submission and completion can happen freely from different threads. Ideally, we would just push an entry to SQ and have a separate goroutine listening for completion waiting, and whenever we see an entry, we make a callback and go back to waiting. Remember how we can use io_uring_enter to do just completion? Here is one such example! This still makes one syscall per CQE entry, and we can even optimize it further by specifying number of CQE entries to wait for.

Coming back to our simplistic model, here’s the pseudo-code of what it looks like:

func ReadFile(path string, cb func(buf []byte)) error {

f, err := os.Open(path)

fi, err := f.Stat()

submitChan <- &request{

code: opCodeRead,

f: f,

size: fi.Size(),

readCb: cb,

}

return nil

}

func WriteFile(path string, data []byte, perm os.FileMode, cb func(written int)) error {

f, err := os.OpenFile(path, os.O_WRONLY|os.O_CREATE|os.O_TRUNC, perm)

submitChan <- &request{

code: opCodeWrite,

buf: data,

f: f,

writeCb: cb,

}

return nil

}

submitChan sends the requests to our main workhorse which takes care of submitting them. Here is the pseudo-code for that:

queueSize := 0

for {

select {

case sqe := <-submitChan:

switch sqe.code {

case opCodeRead:

cbMap[sqe.f.Fd()] = cbInfo{

readCb: sqe.readCb,

close: sqe.f.Close,

}

C.push_read_request(C.int(sqe.f.Fd()), C.long(sqe.size))

case opCodeWrite:

cbMap[sqe.f.Fd()] = cbInfo{

writeCb: sqe.writeCb,

close: sqe.f.Close,

}

C.push_write_request(C.int(sqe.f.Fd()), ptr, C.long(len(sqe.buf)))

}

queueSize++

if queueSize > queueThreshold {

submitAndPop(queueSize)

queueSize = 0

}

case <-pollChan:

if queueSize > 0 {

submitAndPop(queueSize)

queueSize = 0

}

case <-quitChan:

return

}

}

cbMap maps the file descriptor to the actual callback function to be called. This is used when the CGo code calls into the Go code signalling an event completion submitAndPop calls io_uring_submit_and_wait with the queueSize and then pops off entries from CQ.

Let’s look into what C.push_read_request and C.push_write_request does. All they do essentially is push a read/write request to the SQ.

They look like this:

int push_read_request(int file_fd, off_t file_sz) {

struct file_info *fi;

struct io_uring_sqe *sqe = io_uring_get_sqe(&ring);

io_uring_prep_readv(sqe, file_fd, fi->iovecs, total_blocks, 0);

io_uring_sqe_set_data(sqe, fi);

return 0;

}

int push_write_request(int file_fd, void *data, off_t file_sz) {

struct file_info *fi;

struct io_uring_sqe *sqe = io_uring_get_sqe(&ring);

io_uring_prep_writev(sqe, file_fd, fi->iovecs, 1, 0);

io_uring_sqe_set_data(sqe, fi);

return 0;

}

And when submitAndPop tries to pop entries from CQ, this gets executed:

int pop_request() {

struct io_uring_cqe *cqe;

int ret = io_uring_peek_cqe(&ring, &cqe);

struct file_info *fi = io_uring_cqe_get_data(cqe);

if (fi->opcode == IORING_OP_READV) {

read_callback(fi->iovecs, total_blocks, fi->file_fd);

} else if (fi->opcode == IORING_OP_WRITEV) {

write_callback(cqe->res, fi->file_fd);

}

io_uring_cqe_seen(&ring, cqe);

return 0;

}

The read_callback and write_callback just get the entry from cbMap with the passed fd and call the required callbacks to the function that originally made the ReadFile/WriteFile call.

func read_callback(iovecs *C.struct_iovec, length C.int, fd C.int) {

var buf bytes.Buffer

cbMut.Lock()

cbMap[uintptr(fd)].close()

cbMap[uintptr(fd)].readCb(buf.Bytes())

cbMut.Unlock()

}

func write_callback(written C.int, fd C.int) {

cbMut.Lock()

cbMap[uintptr(fd)].close()

cbMap[uintptr(fd)].writeCb(int(written))

cbMut.Unlock()

}

And that’s basically it! An example of how to use the library would be like:

err := frodo.ReadFile("shire.html", func(buf []byte) {

})

if err != nil {

}

Feel free to check out the source to get into the nitty-gritties of the implementation.

No blog post is complete without some performance numbers. However, proper benchmark comparison of I/O engines would probably require another blog post in itself. For the sake of completeness, I will just post results from a short and unscientific test on my laptop. Don’t read too much into it because any manner of benchmarks are highly dependent on the workload, queue parameters, hardware, time of the day, and the color of your shirt.

We will use fio which is a nifty tool written by Jens himself to benchmark several I/O engines with different workloads, supporting both io_uring and libaio. There are far too many knobs to change. But we will perform a very simple experiment using a workload of random read/writes with a ratio of 75/25, using a 1GiB file, and varying block sizes of 16KiB, 32KiB and 1MiB. And then we repeat the entire experiment with queue sizes of 8, 16, and 32.

Note that this is io_uring in its basic mode without polling, in which case, the results can be even higher.

Conclusion

This was a pretty long post, and thank you for reading this far!

io_uring is still in its nascent stages, but it’s quickly gaining a lot of traction. A lot of big names (e.g., libuv and RocksDB) already support it. There is even a patch to nginx that adds io_uring support. Hopefully native Go support is something that lands soon.

Each new version of the kernel gets new features of the API, and more and more syscalls are starting to be supported. It is an exciting new frontier for Linux performance!

Below are some of the resources that I have used to prepare for this post. Please do check them out if you want to learn more.

And lastly, I would like to thank my colleagues Ibrahim and Claudio for proofreading and correcting my horrible C code.

Any questions or comments? Please join us on community.mattermost.com and message me there @agnivade.

Resources