This article is written with an eye toward software design - specifically of an extremely scalable and portable JSON processor.

Introduction

Update: Fixed windows compilation issues, as per the article comments. I'm flying blind without a windows machine right now so a big thank you to Randor for helping me get that sorted out.

Update 2: Big project changes, including integrating PlatformIO builds for ESP32, Arduino Mega 2560 and native machines. *You'll need PlatformIO w/ VS Code and the appropriate packages installed for those boards. I'm not including this with the zip file here as it's too big. It's available on GitHub.

I've been writing articles about JSON (C++) as it evolves, and this latest article introduces a codebase with dramatically improved performance while retaining its tiny memory footprint.

Furthermore, I've decided to approach this from a higher level, and allow you to fall back on my older content for more boots on the ground specifics. With the previous article, I think it was too hard for the reader to know where to begin with it. I aim to connect with you better this time, and show you how this represents an architecturally significant improvement in JSON processing which enables demand streaming for JSON on virtually any device.

I won't be drowning you in UML, or a system inundated with a myriad of "industry standard" design patterns. There's a time and place for that, and it's called enterprise software*. We're taking a very streamlined approach I use for most projects. Gathering and identifying functional requirements plays the primary role, with design decisions flowing from that, before finally getting into the code. It's a very simple process, admittedly, and you'd want to do more with larger professional projects than you would here. This is good for breaking down single developer projects so they aren't overwhelming, and then taking those projects and explaining them to other people.

* I'm half kidding here. The truth is all that stuff is useful to understand and to practice - even in your own projects as it can improve your ability design software as well as to work on large projects and with large or disparate teams of developers and just in general make you a better developer. At the same time, it's usually overkill for a developer working alone.

Conceptualizing this Mess

Typically, JSON processors validate entire documents and parse them into memory trees. This is quite useful for a number of scenarios but doesn't lend itself to big data, where we need time and space efficiency improvements orders of magnitude over common JSON processing algorithms.

The thing about big data, is it's relative. A 200kB file that's too small to provide consistent benchmarks on my PC can take several seconds to process on an 8-bit Arduino Atmega2560, even with performance improvements.

To handle big data, you need a JSON processor that's built with it in mind. Traditional processing falls down for bulk loading gigabytes and handling "chunky" online dumps of data on tiny devices due to the same issue - the data is just too big for the machine with traditional JSON processing. It makes sense to solve both of these issues using the same code, since it's the same problem, and to make that code run on any device so it's all worthwhile.

To that end, I propose a better way to process JSON. I arrived at a set of functional requirements iteratively by envisioning use cases through a sizeable real world document, and through learning from my previous iterations of the design, which I even coded. It's not perfect, because use case scenarios are best driven by the user, not the developer themselves, but when working alone on your own projects, some liberties must be taken. Here are the functional requirements, in an informal presentation:

- *The end developer, not the engine, gets to dictate memory requirements. This is to facilitate working in constrained environments, while scaling to more capable machines.

- The JSON processor must take advantage of significant hardware features to improve performance

- *The JSON processor must be portable, even down to an 8-bit platform.

- *The JSON processor shall not use more memory than is needed for members/locals and only contain the resultset specifically requested for a given query.

- *Realistic queries and their results must be able to fit into less than 4kB of space so this can run comfortably on an Arduino.

- The JSON processor must allow the developer to granularly retrieve JSON elements even from deep within the document.

- The JSON processor must support several input sources, or allow you to implement your own.

- The JSON processor must provide optimized searching and navigation.

- *The JSON processor must accept all documents that conform to the spec, even limitless precision numbers and large BLOB fields.

- *The JSON processor must allow for round tripping of all scalar values, except for string escapes which may be converted to equivalent representations.

- *The JSON processor may impose limits on numeric representations in value space, but no limits are allowed on any kinds of value in lexical space except for possible platform specific stream/file size limits.

* These features are what distinguish this JSON processor from most other offerings.

I used the terms lexical space and value space above. In a nutshell, these concepts have to do with how data is represented. If we're looking at a number as a series of characters, then we are examining it in lexical space. If we are looking at a number as its numeric representation (such as holding it with an int or a double), then this is value space. For the purpose of this article, and for using the processor, it really helps to understand these concepts because they are quite different in terms of what you can do with them. It should be noted that JSON is a lexical specification. Although it has numbers in it, it specifies no value space representation for those numbers. It doesn't indicate for example, that it must fit into 64-bits. In fact, the only limitation on a number in JSON is that it conform to the regular expression (\-?)(0|[1-9][0-9]*)((\.[0-9]+)?([Ee][\+\-]?[0-9]+)?)

Dealing With Arbitrary Length Values

That means in order to accept all documents, we must accept numbers of any length. That doesn't mean we have to represent them in value space though. This JSON processor can produce a perfect lexical representation of any length of number, and it makes a best effort attempt to represent it faithfully in value space. Large values may overflow, however. The JSON specification allows processors to impose platform limits on numbers, but as this JSON processor is intended to be cross platform, the limits shouldn't be dramatically different for different environments, if avoidable, and it's because of this we allow for perfect lexical representations. Still, we can't avoid different limits on value space representations based on platform. This ability for limitless precision in lexical space also serves as the basis for being able to round trip numbers. If you want to round trip a number, get it in lexical space. You can get the number as either or both, depending on what you need.

We must of course, also accept other scalar fields of any length, meaning we can't impose length limits on string values, either.

On its face, this flatly contradicts the aforementioned requirements for this project as they pertain to memory use. What about a 20MB string field or a number with 1000 zeroes? To get around the memory requirements for such values, we can stream any value in chunks, and the JSON processor does that automatically. Currently, there is sometimes a limit on the length of field names, set by the developer, but even this can be avoided with the right queries. A "capture buffer" to hold a field name or a value chunk (called a "value part" in the code) may be as small as 5 bytes in length - 4 bytes for the longest Unicode codepoint in UTF-8, and 1 byte for the null terminator, but it can be as large as you want, assuming you have the RAM. Values are only chunked if they are longer than the available capture buffer. Chunking is efficient enough that even doing a lot of it doesn't impact performance that much. Because of this, there's very little reason to allocate a lot of capture buffer space unless you have really long field names you need to retrieve, since they can't be streamed/chunked. The bottom line is that the only limit on the size of your capture buffer is 5 bytes or the length of the longest field name you need to retrieve padded by four bytes, whichever is greatest. This brings us to memory management.

Handling Memory

To fulfill the memory related requirements of the project, we use two forms of memory scheme. One is a dedicated capture buffer that is attached to the input source, which we touched on in the prior section. The size of this is set by the developer. The other scheme is called a "memory pool" (implemented by MemoryPool derivatives) which is a general purpose microheap whose size is set by the developer as well. It supports fast allocation but not individual item deletion. Because of this, performance is consistent since there's no fragmentation. Allocating and deleting from a pool is so efficient that it's almost free. All data must be freed from a pool at once, but you can use as many different pools as you want to perform different parts of a query. One pool is virtually always enough though. A memory pool is passed in to any method that needs to allocate RAM to complete its operation. Usually, you'll free that pool once the operation is complete and you've used the data you retrieved. Often times, that means freeing the pool many times over the course of a single query. For example, you may get several "rows" of result back but you just need to print them to the console one at a time, so after retrieving each "row", you print it and then free the pool since you don't need that row's data anymore. Here, I'm using "row" simply as a familiar term for a single result of a resultset. Where it's possible, the system attempts to adjust itself to how much memory you give it, but that's not always possible. Sometimes, a query just needs more memory than you dedicated to the pool. In that case, it's often possible to redesign queries to avoid relying on in-memory results as much, if at all, but it usually means writing more complicated code.

Flexibility of Input Sources

The C++ standard does not dictate portable functions for things like HTTPS communication. Rather than provide my own implementations of all the different I/O you can use, I've created a base class called LexSource that implements a specialized forward only cursor over some input. This fullfills the requirement that the JSON processor allow for custom input sources. I did not use the C++ iterator model due to an important specialization for optimization reasons which simply doesn't exist on an iterator interface but must exist on my class. I didn't use it because the LexSource has an integrated capture buffer whose logic is intertwined with reading for efficiency. No such interface exists on iterators. I also didn't use it because it tends to make you reliant on the STL and I wanted to avoid that for reasons having to do with portability and compliance on the platforms this targets. I'll get into specifics later. However, a std::istream interface or iterator can easily be plugged into this library. In fact, any input source can. All you need to do is derive from LexSource and implement read() which advances by one as it returns the next byte in the (UTF-8 or ASCII) stream or one of a few negative fail conditions if input isn't available. If your underlying input source supports an optimized way to look for a set of characters, you can implement skipToAny() to make searching and skipping much faster but it's optional, can be a little tricky to implement, and not every source can take good advantage of this. Therefore, a default implementation is provided that simply calls read(). With memory mapped files, skipToAny() is extremely effective. Buffered network I/O might be another area that could benefit. The JSON processor uses a LexSource as its input source. I've implemented several, including two different file implementations, an Arduino Stream based one, and one over a null terminated string - ASCII or UTF-8. If you need to make a custom one, look to those for an example.

Tackling Portability

This library was written as a header-only library for C++11. It will compile and run on Arduinos, on Linux, on Windows, and should work on Apple, and Raspberry devices as well as various IoT offerings like the ESP32 with little to no modification. If anyone has problems getting it to compile, leave a comment, since I haven't been able to test it on all these platforms yet.

With portability comes certain design considerations. For example, the library avoids using CPU specific specialized SIMD instructions, relying instead on the optimizations in the C standard library, which often utilize said instructions. We also avoid generic programming in this library as to avoid the code bloat, it tends to introduce as well as usually forcing reliance on STL implementations which on the Arduino is pretty much non-existent. Furthermore, some STL implementations unfortunately deviate from the standard and from each other (although in recent years, some of the more naughty implementations have been replaced by ones that are more standard).

Certain features, such as memory mapped files are simply not available on certain platforms. Such features are factored so that they can be included if needed, but nothing relies on them. This is so we can meet functional requirements in terms of competitive performance while also maintaining relative portability. Where possible, platform specific features are implemented for multiple platforms. Memory mapped files are supported on both Windows and Linux, for example.

Pains were taken to support Arduino devices, since their codebase is one off (supporting certain C++ things and not others) so that this can target popular 8-bit processors. I haven't tested it with 8-bit processors other than the ATmega2560, but as long as they can operate on a 32-bit value (even if they don't have special instructions for it) and as long as they have some floating point support, they should be able to handle it ... slowly. Of course, you don't have things like memory mapped file I/O or really most of the LexSource implementations, but the StaticArduinoLexSource<TCapacity> takes a Stream which Arduino uses for files, network connections, and serial, allowing you to use any of those. The great thing is your query code will all still work because the JSON processor has all the functionality it does on the full size platform exposed in the same way.

Making It Perform

Standard parsing over data retrieved by fgetc() and even fread() simply can't deliver the sort of throughput that some modern JSON processors are capable of. In order to make this package competitive with other offerings, it contains many optimizations, some relatively unique to this library:

- Pull parsing - This library uses a pull parser in order to avoid recursion and to save memory as well as provide efficient streaming support.

- Partial parsing - This library will not parse the entire document unless you ask it to. It does fast matching for key markers in the document to find what you want. While especially well suited to machine generated JSON, it doesn't report well formedness errors as robustly as a fully validating parser will. This is a design decision made for performance. There is no requirement that this software reject all invalid documents. The requirement is simply that it accepts all valid JSON documents. It will usually detect errors, just sometimes not as early as other offerings.

- Denormalized searching - This library does not load or otherwise normalize and store any data that isn't specifically requested. Strings are undecorated and/or searched for in a streaming fashion right off the "disk"/input source and not loaded into RAM. This limits the number of times you have to examine strings and also saves memory.

- Memory Mapped I/O - This is the one area where this library is somewhat platform specific. Not all platforms have this feature but major operating systems do. On those that do, you can see 5x-6x improvements in speed with this library. This is how you can approach or perhaps even break 1GB/s processing JSON on a modern workstation (meaning computers other than my relic). This and the use of the optimized

strpbrk() function in tandem with it fulfills the requirement of taking advantage of significant hardware features to improve performance, since strpbrk() is almost always highly optimized. - Fast DFA streaming value parsing. In order to support arbitrary length numbers, this implementation uses hand built DFA state machines to parse numbers and even literals progressively on demand, only as requested. Most JSON processors must load entire numbers into RAM in order to parse them into a double or integer. This library does not have that requirement, meaning it can stream values of arbitrary size, it can be aborted in the middle of such a streaming operation, and it can delay parsing into value space on a character by character basis. It iteratively parses as it chunks.

On my antique of a PC, I get these results over a 200kB pretty printed JSON document:

Extract episodes - JSONPath equivalent: $..episodes[*].season_number,episode_number,name

Extracted 112 episodes using 23 bytes of the pool

Memory: 324.022283MB/s

Extracted 112 episodes using 23 bytes of the pool

Memory Mapped: 331.680991MB/s

Extracted 112 episodes using 23 bytes of the pool

File: 94.471541MB/s

Episode count - JSONPath equivalent: $..episodes[*].length()

Found 112 episodes

Memory: 518.251549MB/s

Found 112 episodes

Memory Mapped: 510.993124MB/s

Found 112 episodes

File: 99.413921MB/s

Read id fields - JSONPath equivalent: $..id

Read 433 id fields

Memory: 404.489014MB/s

Read 433 id fields

Memory Mapped: 382.441395MB/s

Read 433 id fields

File: 95.012784MB/s

Skip to season/episode by index - JSONPath equivalent $.seasons[7].episodes[0].name

Found "New Deal"

Memory: 502.656078MB/s

Found "New Deal"

Memory Mapped: 495.413195MB/s

Found "New Deal"

File: 97.786336MB/s

Read the entire document

Read 10905 nodes

Memory: 76.005061MB/s

Read 10905 nodes

Memory Mapped: 76.837467MB/s

Read 10905 nodes

File: 65.852761MB/s

Structured skip of entire document

Memory: 533.405103MB/s

Memory Mapped: 516.783414MB/s

File: 100.731389MB/s

Episode parsing - JSONPath equivalent: $..episodes[*]

Parsed 112 episodes using 5171 bytes of the pool

Memory: 69.252903MB/s

Parsed 112 episodes using 5171 bytes of the pool

Memory Mapped: 68.221595MB/s

Parsed 112 episodes using 5171 bytes of the pool

File: 58.409269MB/s

Read status - JSONPath equivalent: $.status

status: Canceled

Memory: 546.021376MB/s

status: Canceled

Memory Mapped: 528.611999MB/s

status: Canceled

File: 86.431820MB/s

Extract root - JSONPath equivalent: $.id,name,created_by[0].name,

created_by[0].profile_path,number_of_episodes,last_episode_to_air.name

Used 64 bytes of the pool

Memory: 527.238570MB/s

Used 64 bytes of the pool

Memory Mapped: 510.993124MB/s

Used 64 bytes of the pool

File: 100.123241MB/s

I picked this versus the 20MB bulk document I use for benchmarking because I can ship the smaller version with the project, but you'd have to generate the 20MB one yourself. This tends to get higher throughput with larger files, at least on PCs. The more dense your data is, the lower the throughput count, although it's actually the same "effective" speed since it's not counting advancing dead space.

In each of these benchmarks, I'm comparing three different access methods: The first one is using a 200kB in-memory null terminated string. The second one is using a memory mapped file. The final method is using a standard file with fgetc() under the covers. I used to have one that used fread() as well but surprisingly, my performance wasn't any better so I removed it, since the buffering just required extra memory.

For perspective, my ESP32 IoT device runs these benchmarks at about 73kB/s on average and the poor little 8-but Arduino runs them at a brisk 23kB/s on average. I want to get out and push! Still, it runs, and you'll not have to worry about the size of your input. It should handle most anything you throw at it, within even slight unreason.

Providing Navigation and Searching

These are both covered by the skipXXXX() methods on JsonReader. Using these methods allows for high speed extremely selective navigation through a document. You can move to specific fields on one of three axes, you can skip to a specific index of an array, and you can skip entire subtrees extremely quickly. These have the distinction of being the fastest way to move through a lot of JSON text. The skip methods never load data into RAM and never start a full parse, with the exception of the skipToFieldValue() convenience method which simply calls skipToField() and then calls read() once for you after you've found a field. Taken together, these methods fulfill the requirements for efficient searching and navigation features.

Granularly Extracting Data

Naturally, you'll want data out of your document at some point, and while you can use skipXXXX() and read() in many situations, there's another way to handle this, by way of an "extraction". Extractions are precoded navigations that retrieve several values in one efficient operation. Using the raw reader functions we've explored is usually more flexible and efficient, but it's also difficult to navigate with it. Furthermore, there's a common operation that it just can't handle both efficiently and correctly: Retrieving the values of multiple fields off of the same object. You might think you can use skipToField() in a loop passing it different field names each time, but the problem is JSON fields are unordered, meaning you can't assume what order they appear in the document. The reader can't back up so let's say you want an id and a name. You can call skipToField("id", JsonReader::Siblings) followed by skipToField("name",JsonReader::Siblings) but that only works when the id comes before the name in the document - which you cannot rely on according the specification! If you want to search for multiple field names, you could iterate through all the fields using read() and pick what you want but you really should use an extraction instead wherever you can. read() is more expensive in terms of time/space requirements.

Extractions allow you to quickly grab multiple field values or array items as well as subitems in a single operation. Their primary limitation is that they must return a fixed number of values. You cannot run a "query" that returns a result list of arbitrary length with extractions. You must use the reader to navigate, extract a fixed number of values from a smaller portion of the document, navigate again and repeat. Eventually, I will produce either a query engine or a code generation engine to facilitate building complicated queries, perhaps using a non-backtracking subset of JSONPath. Extractions aren't queries themselves. Queries encompass both navigation/searching and extraction. Extractions are just building blocks of queries. Sometimes, queries don't even need extractions, for example, if you just want to retrieve a single value off of an object.

Extractions will only retrieve numeric values in value space, not lexical space so you can't round-trip using an extraction currently. This may be changed in the future, with the caveat that it could explode RAM usage. Extracted values must be entirely loaded into memory since they cannot be streamed. You must use read() off the reader to get a numeric value in lexical space.

Extractions fulfill the requirement of granular data retrieval and especially combined with navigation/searching fulfills the requirement of being able to retrieve that precisely located data deeply in the document. They contribute to the requirement of making queries fit comfortably in 4kB of RAM as well, because despite using more RAM than raw reading does, between using a pool that can be freed after each result row is processed, and being able to extract only needed scalar values, it's very conservative about the memory it does use.

Extractions are composed of a series of JsonExtractor structures that nest, with one root. Three types of extractors are available, and which type it is depends on the constructor called:

- Object extractors extract field values off of object elements

- Array extractors extract items at specific indices out of arrays

- Value extractors extract a single value at the current location

You basically compose these. The first two are navigation, the third does the actual extraction. The first two are used together to compose a kind of compound path (actually multiple simultaneous paths) through the document, and at the end of the paths, you'll have value extractors to get the data you just pointed to.

Array and object extractors, as mentioned can retrieve multiple fields or indices simultaneously, so as I said, you can navigate multiple paths at the same. A value extractor meanwhile is linked to a variable you gave it that will be set upon extraction.

You use them by declaring the variables that will hold your data, then declaring the nested structures. You can then take the root structure and pass it to extract() to fill your values with the data relative to the current location in the document. This last bit is important, because it allows you to reuse an extractor multiple times in different places in the document. This is very useful for extracting arbitrary length lists of results because for each row you use the reader to navigate, and then call extract() with the same extraction each time. We do this when we're benchmarking pulling TV episode data out of a large JSON data dump.

We've covered a lot about these for now, and we'll get into detail later.

In-Memory Trees

This doesn't directly fulfill a functional requirement in and of itself, but it facilitates extractions because we need to be able hold JSON data around in memory in order to perform them. I could have placed a limit on extractors so that you could only extract scalar JSON values, and not extract object or array values with value extractors, but it wouldn't have made the code much simpler. It might have even complicated it.

Therefore, we can hold any JSON elements around in memory, usually using a MemoryPool, although if you build JSON trees yourself (not recommended), it's not a requirement to use a pool - your memory can come from anywhere.

JsonElement is a sort of variant that can represent any type of JSON element, be it an object, an array, or a scalar value like a string or an integer. Data is held in value space. There's no facility for preserving the lexical representation of values, and this would make RAM use prohibitive in certain situations since they aren't streaming. Generally, you can query for the type() of the value it holds and then use the appropriate accessor methods like integer(), real() or string() to get scalar values out of it. Objects and arrays are held in linked lists whose head is available at either pobject() or parray(), respectively and accessible via fieldname or index using operator[]. I won't get into details of building the trees manually here, since this was not designed for that, nor is editing objects, arrays or strings efficient. Note that field names are not hashed. Do not think you can efficiently retrieve fields off of large in-memory objects this way. It's not what the library was designed to do. Most other JSON libraries are.

The primary use for a JsonElement is for holding values that are extracted using value extractors. You can link a JsonElement variable to your value extractor and it will be filled with the data you asked for.

You can also call extract() on a JsonElement itself so you can extract data from an in-memory tree the same way you do with a reader. This is simply so you can hold arbitrary length lists of query data around in memory as a JSON array or object if you absolutely must, and then extract the relevant data from this after the fact. Basically, it's so you can hold whole resultsets in memory as JSON arrays, and then work off of them, but I will not make wrappers to make this technique easy to use because it flies in the face of the RAM requirements imposed on this library. If you find yourself using this code this way, you might be better off with a different JSON processor.

We've now covered the functional requirements and overarching design elements of this JSON processor. It's time to dive into the code.

Coding this Mess

Getting Started

I've provided a project that works in VSCode, with PlatformIO and an ATmega2560 or a Linux workstation with gcc as is. You'll have to modify your board settings to match your device if you're going to use PlatformIO with it. As I said, it's currently set up for an ATMega2560, but also there's an ESP32 board setting commented out in the same platformio.ini file. If you use compilers other than gcc and/or debuggers other than gdb, you'll have to add other build tasks to tasks.json yourself, and configure launch.json the way you want it. The project can be modified to use an INO file that simply #includes main.cpp and it should get the ArduinoIDE to build it. Don't use the main.cpp in your INO because the preprocessor definitions tend to confuse the IDE and it mangles the code it produces if it will even build. You can try to create a Visual Studio solution for it, but I actually haven't tried this on Windows yet because my Windows machine is down. For those of you that use Windows, I encourage you to try to compile and use this. It should build and run.

Generating Bulk Data

I've provided BulkTemplate.txt with the project which provides a template for generating 20MB worth of pretty printed JSON that will work with the queries in the benchmark app. You can use it with this website at https://www.json-generator.com/ though it involves abusing the clipboard and your (least) favorite text editor. The website won't like you very much, but we're not here to make friends with it. I can't guarantee your IoT devices will handle it simply because I haven't waited around for it to be parsed at 22kB/s. It's designed to so there's nothing immediately that I can think of that would prevent it except for possible integer overflows. I've tried to design it for example, so that if the position overflows, it won't kill the parsing when it goes negative. We'll see how these measures work in practice.

Exploring the Code

The benchmark code covers all the major features of the library, but it's quite long as a result.

This isn't going to be heavy on code, but we'll cover some of the core features. Let's start with extracting episode information from the document because this illustrates all the major components of performing a query, searching/navigation and extraction.

StaticMemoryPool<256> pool;

JsonElement seasonNumber;

JsonElement episodeNumber;

JsonElement name;

const char* fields[] = {

"season_number",

"episode_number",

"name"

};

JsonExtractor children[] = {

JsonExtractor(&seasonNumber),

JsonExtractor(&episodeNumber),

JsonExtractor(name)

};

JsonExtractor extraction(fields,3,children);

JsonReader jr(fls);

unsigned long long maxUsedPool = 0;

int episodes = 0;

while(jr.skipToFieldValue("episodes",JsonReader::Forward)) {

if(!jr.read())

break;

while(!jr.hasError() && JsonReader::EndArray!=jr.nodeType()) {

if(pool.used()&gt;maxUsedPool)

maxUsedPool = pool.used();

pool.freeAll();

++episodes;

if(!jr.extract(pool,extraction)) {

print("\t\t");

print(episodes);

print(". ");

print("Extraction failed");

println();

break;

}

if(!silent) {

print("\t\t");

print(episodes);

print(". ");

printSEFmt((int)seasonNumber.integer(),(int)episodeNumber.integer());

print(" ");

print(name.string());

println();

}

}

}

if(jr.hasError()) {

print("\tError (");

print((int)jr.error());

print("): ");

print(jr.value());

println();

return;

} else {

print("\tExtracted ");

print(episodes);

print(" episodes using ");

print((long long)maxUsedPool);

print(" bytes of the pool");

println();

}

First of all, I have to apologize for not using cout or even printf() but Arduinos tie my hands since they don't have it, or have an incomplete implementation. I had to make these print() things instead. On Arduinos, it dumps to the first Serial port. On anything else, it writes to stdout.

The first thing we do is allocate a pool since extract() requires one to hold your result data around with. I've allocated a whopping 256 bytes, which is far more than we need. In data.json, we could get away with about 1/10th of that but a larger pool gives us some breathing room for holding longer episode names than we have in that file. Additionally, internally extract() uses some extra bytes as scratch space, but they never get reported, so you always want a little room. This is a typical scenario. You don't need to reserve a lot of space, because queries are extremely RAM efficient, but even that having been said, you'll still usually reserve a lot more than you end up using, just to be safe.

Next, we declare the JsonElement variables that will hold the results on each call to extract(). We need three for the three fields we're extracting.

Now we declare an array of the field names we want, and then an array of JsonExtract(&var) value extractors, which we pass as children to the object extractor we declare next. This leaves us with our root:

JsonExtractor extraction(fields,3,children);

Note that the size of your fields array, the size of your children array, and your count must all match. If they don't (cue foreboding music), the results are undefined. That's the polite way of saying you'll probably crash.

Now we've built our extractor, but we can't use it yet. Extractions are always relative to where you are in the document. If we ran extract() right now, we'd get "Burn Notice" for the name and <No Result>/<Undefined> for the season and episode numbers because they don't exist on the root object.

So before we can use our extraction, we must navigate. So we create a JsonReader and then essentially navigate like this: $..episodes

The trick to that is this line:

while(jr.skipToFieldValue("episodes",JsonReader::Forward))

This will do a fast forward search through the document for any field called episodes and then move to the value. It does not consider where the field occurs in the hierarchy. That's good enough for our purposes, and it's fast. An alternative might be to do $.seasons[*].episodes but that's more complicated.

Whenever we land on one, we'll be on its Array node. From there, we start traversing each array value. We have to do this with navigation rather than use an extraction for it because extractions cannot return resultsets of arbitrary length. One variable maps to one element retrieval. The only way to extract() all items of an array whose count isn't known is to use a value extractor on the entire array and hold it all in memory. This is not recommended, nor is this engine designed with that in mind. The alternative is to do what we're doing, which is to navigate to each element of the array in turn, and call extract() from that position:

while(!jr.hasError() && JsonReader::EndArray!=jr.nodeType()) {

if(pool.used() > maxUsedPool)

maxUsedPool = pool.used();

pool.freeAll();

++episodes;

if(!jr.extract(pool,extraction)) {

print("\t\t");

print(episodes);

print(". ");

print("Extraction failed");

println();

break;

}

if(!silent) {

print("\t\t");

print(episodes);

print(". ");

printSEFmt((int)seasonNumber.integer(),(int)episodeNumber.integer());

print(" ");

print(name.string());

println();

}

}

Once we remove all the fluff, it's simple. While there are still elements in the array, and no errors, we free the pool of any previous data since we no longer need it, and increment an episode count that we don't really need - we just use it for statistics. The main thing here is the next line, where we call extract() passing it our extraction. Each time, assuming it succeeds, the JsonElement variables we declared earlier and linked to value extractors will be filled with the results of the extraction at the current location - the object in the array we navigated to. If it fails, that indicates some kind of error parsing the document, so check the error code. Not finding values does not indicate a failure. If a value is not found, its associated variable type will be Undefined. Note how we're printing the values immediately afterward. When we reach the end of the array, the outer loop will take us to the next episodes field in the document and the process repeats.

It should be noted that extract() operates on your current logical position and then advances the cursor over the element at that position. For example, if you're on an object, by the time extract() is done, it will have read past that object, positioning the reader on to whatever follows it. The same applies for arrays and scalar values. Extract essentially "consumes" the element it is positioned on. We take good advantage of that above, since simply calling extract() there moves us to the next item in the array.

Above, we were only interested in examining a single object at once, but you aren't limited to that. You can create extractions that drill down and dig values out of the hierarchy at different levels:

DynamicMemoryPool pool(256);

if(0==pool.capacity()) {

print("\tNot enough memory to perform the operation");

println();

return;

}

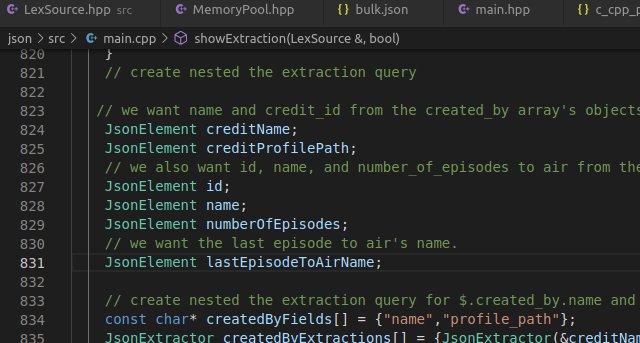

JsonElement creditName;

JsonElement creditProfilePath;

JsonElement id;

JsonElement name;

JsonElement numberOfEpisodes;

JsonElement lastEpisodeToAirName;

const char* createdByFields[] = {

"name",

"profile_path"

};

JsonExtractor createdByExtractions[] = {

JsonExtractor(&creditName),

JsonExtractor(&creditProfilePath)

};

JsonExtractor createdByExtraction(createdByFields,2,createdByExtractions);

JsonExtractor createdByArrayExtractions[] {

createdByExtraction

};

size_t createdByArrayIndices[] = {0};

JsonExtractor createdByArrayExtraction(createdByArrayIndices,1,createdByArrayExtractions);

const char* lastEpisodeFields[] = {"name"};

JsonExtractor lastEpisodeExtractions[] = {

JsonExtractor(&lastEpisodeToAirName)

};

JsonExtractor lastEpisodeExtraction(lastEpisodeFields,1,lastEpisodeExtractions);

const char* showFields[] = {

"id",

"name",

"created_by",

"number_of_episodes",

"last_episode_to_air"

};

JsonExtractor showExtractions[] = {

JsonExtractor(&id),

JsonExtractor(&name),

createdByArrayExtraction,

JsonExtractor(&numberOfEpisodes),

lastEpisodeExtraction

};

JsonExtractor showExtraction(showFields,5,showExtractions);

JsonReader jr(ls);

if(jr.extract(pool,showExtraction)) {

if(!silent)

printExtraction(pool,showExtraction,0);

print("\tUsed ");

print((int)pool.used());

print(" bytes of the pool");

println();

} else {

print("extract() failed.");

println();

}

Here, we're creating several nested object extractors and even threw an array extractor in for good measure. The query translates roughly to the following JSONPath:

$.id,name,created_by[0].name,created_by[0].profile_path,

number_of_episodes,last_episode_to_air.name

I'm not sure if that's syntactically proper for JSONPath but the idea should hopefully be clear. Since we're already on the root when we start, we just extract() from there.

There's currently a significant limitation to this query setup and that is that it is currently impossible to do certain kinds of non-backtracking queries, such as when you want to get multiple fields off an object as well as recursively drill down indefinitely into one of its fields. I will be adding a sort of callback extractor that will notify you as extractions arrive so you can retrieve an arbitrary series of values.

Conclusion

main.cpp has plenty of code in there to get you started. Hopefully, this article demonstrated what I set out to - software by design, by way of a scalable JSON processor. The functional requirements gathering here was abbreviated and informal, and produced a set of equally informal design decisions, but that was enough to produce software that met its goals. A little bit of upfront planning goes a long way.

History

- 30th December, 2020 - Initial submission

- 31st December, 2020 - Update 1 - fixed compilation issues on windows + MSVC

- 1st January, 2020 - Update 2 - added PlatformIO builds to GitHub project