I’ve been researching GraphQL for several months now to understand why people choose it, how they implement it, and what might be lacking in the experience for .NET developers. The purpose of this blog post is to share some of those findings as a resource for architects and developers who are either considering GraphQL as part of their solution stack or have already implemented it and want to learn more. I’ll look at what GraphQL is, share benefits and challenges, review the current .NET ecosystem, and walk you through some hands-on examples.

What GraphQL is

In simple terms, GraphQL is an interface to data for front ends. That is significant because it is not designed nor intended to replace backend communications. Other technologies like gRPC are more suited for low latency backplane interoperations. GraphQL can be summarized with the following points:

- It is a query language for APIs.

- It is a specification for mutating data.

- It provides a uniform way to discover capabilities.

- It is a single endpoint for multiple services.

- It is a real-time subscription service.

- It encompasses the runtime to implement these features along with tools to facilitate development, implementation, and testing.

GraphQL was developed by Facebook for Facebook. One of the creators, Lee Byron, stated that it is:

“a data-fetching API powerful enough describe all of Facebook.”

GraphQL uses the traditional HTTP(S) request/response model. Responses are formatted in JSON. Requests use the GraphQL query dialect that is like JSON (but not quite). Using your favorite API testing tool, you can ask any GraphQL endpoint the following question:

{

__schema {

types {

name

kind

description

fields {

name

}

}

}

}

The structure is a way of describing what parts of the object graph are interesting. In this case, the standard __schema request returns the features available from that GraphQL endpoint. Of all the properties available in the schema, this request is only interested in the types collection. Types also contain a lot of information, so we restrict the answer to name, kind, etc. The response from my server includes:

{

"name": "Blog",

"kind": "OBJECT",

"description": null,

"fields": [

{

"name": "id"

},

{

"name": "name"

},

{

"name": "url"

},

{

"name": "posts"

}

]

}

This informs me what properties I can receive that are related to a blog. I can craft a request like this:

{

blogs {

name

}

}

And receive the following response:

{

"data": {

"blogs": [

{

"name": "Blogs on Developer for Life"

},

{

"name": "GeekTrainer"

}

]

}

}

It’s also possible to retrieve multiple data sets in a single request. Here, I’m asking for blog names and post titles.

{

names: blogs {

name

},

posts: blogs {

posts {

title

}

}

}

The response includes both:

{

"data": {

"names": [

{

"name": "Blogs on Developer for Life"

},

{

"name": "GeekTrainer"

}

],

"posts": [

{

"posts": [

{

"title": "Azure Cosmos DB With EF Core on Blazor Server"

},

{

"title": "Explore WebAssembly System Interface (WASI for Wasm) From Your Browser"

},

{

"title": "Blazor State Management"

},

{

"title": "Build a Single Page Application (SPA) Site With Vanilla.js"

}

]

}

]

}

}

You are likely starting to recognize some of the benefits of GraphQL over REST. It is possible to shape the data without having to modify the backend API. You can avoid over-fetching of data by requesting exactly what you want and reduce round trips by receiving multiple payloads in a single response.

Queries can be further refined with filter and sort criteria. GraphQL does not specify a standard for this, so it is implemented by the API provider. For example, this is how GitHub enables me to filter for the following request:

“Give me the first 100 pull requests in the repository named ExpressionPowerTools owned by me that have the label dependencies and are in the MERGED state. Order by most recent PRs first.”

{

repository(name: "ExpressionPowerTools", owner: "jeremylikness") {

label(name: "dependencies") {

pullRequests(states: [MERGED], first: 100, orderBy: {field: CREATED_AT, direction: DESC}) {

totalCount

nodes {

permalink

author {

login

avatarUrl

url

}

createdAt

}

}

}

}

}

Here’s the truncated result:

{

"data": {

"repository": {

"label": {

"pullRequests": {

"totalCount": 5,

"nodes": [

{

"permalink": "https://github.com/JeremyLikness/ExpressionPowerTools/pull/34",

"author": {

"login": "dependabot",

"avatarUrl": "https://avatars0.githubusercontent.com/in/29110?v=4",

"url": "https://github.com/apps/dependabot"

},

"createdAt": "2020-10-14T06:09:51Z"

}

]

}

}

}

}

}

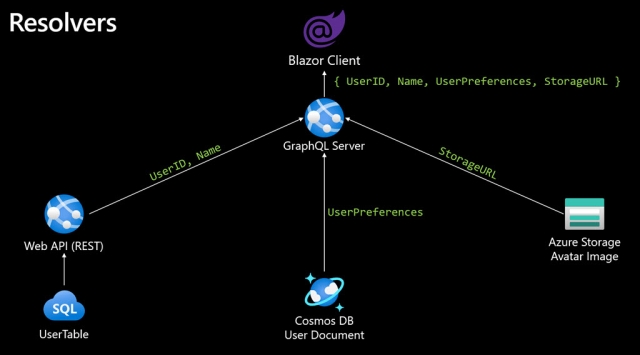

The server is responsible for implementing what are known as resolvers or code that can accommodate a GraphQL request. The client doesn’t need to know where the data comes from. It simply builds its request and waits for the response. Consider a simple request like this:

{

user {

UserID

Name

UserPreferences {

...

}

StorageURL

}

}

The server may have to gather data from multiple services and apply different resolvers to satisfy each part of the request. For example:

UserID and Name can be pulled by connecting to a legacy REST API (which in turn is backed by SQL Server).UserPreferences are stored as a document in Azure Cosmos DB.StorageURL is a reference to the location in Azure Storage that the avatar is located.

Conceptually, an implementation might look like this:

Resolvers provide a way to satisfy heterogenous data requests on the server. Another feature of GraphQL is the ability to integrate data across servers and provide it as a single source and schema. This is referred to as “schema-stitching.”

Schema-stitching

There are two major use cases I’ve come across for schema-stitching.

The first is to manage large schemas and schemas that are owned by multiple teams. In this scenario, each team provides their own GraphQL endpoint that is configured to use the proper resolvers to satisfy requests. Another server is set up that also hosts a GraphQL endpoint. The schemas are stitched together to provide a single, large schema. Clients can request and shape data however they like from a single endpoint while individual teams maintain control over their schema as well.

The first use case is motivated by the need to manage schemas across teams. The second is motivated by functionality. It is possible to expose data from multiple endpoints underneath a single endpoint. This can be very useful and will even work with third-party APIs. If you can reach the GraphQL endpoint, you can configure your own server to include it as part of the schema-stitching process.

Here’s a practical (and real) example. Two APIs exist that take location information as their input. One service is a weather service and provides forecasts for the location. The other service shows restaurants and ratings in the area. Even though the two services are hosted, implemented, and maintained in different places, schema-stitching makes it possible to bring them together. The “new” service lets you pick a location and provides dining options along with the weather.

This is what schema-stitching looks like conceptually:

It should be clear by now how GraphQL retrieves data. What about the times you need to update the data? Let’s look at mutations.

Mutations

Any query can have side effects. You can write whatever code you want. To play nice with consumers of your API, however, GraphQL expects queries with side effects to be marked as mutations. This is where you can implement your C.U.D. (create, update, delete) operations. Mutations work exactly like queries with a data shape and parameters, but they make it clear the result of a call is a change to your backend data. Here’s a simple definition of a mutation:

mutation CreatePostForBlog($blogId: ID!, $post: PostInput!) {

createPost(blogId: $blogId, post: $post) {

id,

posted,

title

}

}

The definition contains variables that must be filled for the request to succeed. Note that the GraphQL type system deals with nullability the exact opposite of .NET. In .NET, primitives are not nullable by default. For an int you must opt-in to nullability by specifying int?. In GraphQL, types are nullable by default. You must opt-in to non-nullability by using the ! exclamation marker. Let’s provide some variables:

{

"blogId": 1,

"post": {

"posted": "2021-06-16",

"title": "GraphQL for .NET Developers"

}

}

If the request succeeds, we’ll receive the details of what just posted:

{

"data": {

"createPost": {

"id": 33,

"posted": "2021-06-16",

"title": "GraphQL for .NET Developers"

}

}

}

Before I go on, I want to cover one other feature of GraphQL: subscriptions.

Subscriptions

Another cool feature of GraphQL is support for subscriptions. These use WebSockets to open a real-time channel that your client uses to subscribe for notifications. The subscription is based on a query. Anytime the subscribed event fires, the server reruns the query and sends the updated results.

⚠ Caution One caveat with subscriptions is that WebSockets don’t have HTTP headers so there is not a standard way to authenticate. Most GraphQL servers implement their own version of authentication but keep in mind it may require using a specific client that honors that protocol.

When to use GraphQL

Is GraphQL right for you? As with most technology solutions, it depends. As a frontend mechanism for fetching data it shines, but it was not built for nor intended to be used for backplane/backend communication between microservices for example. In your server or native cloud environment, you will likely be better served going with a protocol like gRPC for inter-process communication.

Pros

There are a lot of benefits from using GraphQL.

- Client developers can request the data they want, and even change the shape of the data, without needing any changes to the backend.

- The ability to shape the data response and request multiple queries in a single round-trip means less network overhead and avoids “over-fetching” data that isn’t needed.

- The endpoints are discoverable meaning a client can easily query for capabilities and understand what schemas are available to query and mutate.

- The schema provides a contract that ensures the client and server are in sync.

- The single endpoint simplifies the client implementation, as it only needs to have one URL configured as opposed to multiple URLs per area in the app.

- Resolvers exist for most data sources (and can be custom built for any), so it is possible to modernize legacy apps by providing a GraphQL façade to legacy API endpoints.

- Schema-stitching not only makes services more broadly available, but also helps with schema governance because teams can manage their own schema and stitch it into the global one.

- It’s a tried and tested technology implemented in production at major corporations.

GraphQL not all flowers and ribbons. There are some challenges.

Cons

What could possibly go wrong?

- The query syntax is like JSON, but not quite, so it does require a custom approach (or one that relies on an existing library) to form your request, and a little learning curve.

- Subscriptions are only available via WebSockets.

- There is no standard for authentication, although for queries and mutations standard HTTP authorization approaches work fine.

- There is no standard for filtering, paging, or sorting, and implementations vary from library to library.

- Not all implementations provide correlated logging and tracing for troubleshooting.

- Clients can potentially issue extremely deep, recursive, and complex queries that may impact performance of the server.

- Poorly implemented resolvers can result in redundant database calls.

GraphQL and .NET

The GraphQL ecosystem spans multiple languages and platforms. Although .NET was late to adopt support, several popular solutions exist for both the client and the server.

- GraphQL.NET is a package that deserves accolades for choosing a great name. It is heavily downloaded and many developers I spoke to believe (incorrectly) that it is an official Microsoft package.

- HotChocolate came late to the game but is rapidly gaining in popularity. Many developers say they prefer this library due to its support for code-first schemas, schema-stitching, and subscriptions as well as integration with Entity Framework Core.

- GraphQL.EntityFramework provides support to translate GraphQL queries to and from queries that can be passed to EF Core.

There are other libraries but these appear to be the most used. The EF Core team recently invited HotChocolate creator Michael Staib to a community standup. Check this video out to learn more about GraphQL and see how easy it is to integrate into a .NET project.

What’s more fun than watching someone build a GraphQL app? Building one yourself of course!

Your first GraphQL app

I apologize in advance because this section requires some commitment. I don’t have a finished project to download, but all of the steps to build it are in this post. Let’s see how quickly we can get up and running. I’m using .NET Core 5.0 for the demo.

The project

Start by creating an empty ASP.NET Core project:

dotnet new web -o DotNetGQL

Navigate to the newly created directory. Pour some hot chocolate on your project.

dotnet add package HotChocolate.AspNetCore --version 12.0.0-preview.14

Open Startup.cs and add the following to ConfigureServices:

dotnet add package HotChocolate.AspNetCore --version 12.0.0-preview.14

Replace the app.UseEndpoints... statement with this:

app.UseEndpoints(endpoints => endpoints.MapGraphQL("/"));

Run the application and navigate to the web page (by default it should be at https://localhost:5001). You should be presented with some Banana Cake Pop.

This is HotChocolate’s built-in Interactive Development Environment (IDE) for GraphQL. We can’t do much with it yet. Let’s give it something to work with.

The domain

Add the following two classes to your project:

public class Blog

{

public int Id { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

public string Url { get; set; }

public IList<Post> Posts { get; set; }

}

public class Post

{

public int Id { get; set; }

public DateTime Posted { get; set; }

public string Title { get; set; }

public Blog Blog { get; set; }

}

There are several approaches to building GraphQL endpoints, including schema-first (you define the schema in a template file and use that to create the endpoint) and code-first (you declare the schema in code). We’ll use code-first for this demo. Create a class named Query and return some sample data. We’ll use IQueryable to set us up for success later when we turn this into a live database.

public class Query

{

public IQueryable<Blog> GetBlogs()

{

var blog = new Blog

{

Id = 1,

Name = "Developer for Life",

Url = "https://blog.jeremylikness.com",

Posts = new List<Post>

{

new Post

{

Id = 1,

Title = "GraphQL on .NET",

Posted = DateTime.UtcNow.AddDays(-1)

}

}

};

blog.Posts[0].Blog = blog;

return new[] { blog }.AsQueryable();

}

}

Finally, in Startup.cs you can inform the GraphQL server to use Query by adding the highlighted line:

services.AddGraphQLServer()

.AddQueryType<Query>();

Restart the application and refresh the web page. You should be able to select “New Document” and when you start typing, autocomplete will kick in.

I typed the query:

{

blogs {

name

posts {

title

}

}

}

And received the response:

{

"data": {

"blogs": [

{

"name": "Developer for Life",

"posts": [

{

"title": "GraphQL on .NET"

}

]

}

]

}

}

You can also toggle between the document and schema to explore the schema Banana Cake Pop was able to automatically acquire.

Make it real

The last step is to wire up a real database with real data. We’ll use the latest (as of this blog post) EF Core with support for SQLite:

dotnet add package Microsoft.EntityFrameworkCore.Sqlite --version=6.0.0-preview.4.21253.1

We’ll also add HotChocolate’s support for data integration that adds filtering, paging, and sorting to the GraphQL schema and projects to expression trees so EF Core can translate the queries.

dotnet add package HotChocolate.Data --version=12.0.0-preview.14

To enable filtering and sorting of posts within blogs, add a using statement to the file with the class definition for the Blog:

using HotChocolate.Data;

Then add the attributes to the Posts navigation property:

[UseFiltering]

[UseSorting]

public IList<Post> Posts { get; set; }

Next, we create a DbContext. This is how EF Core understands what domain objects should be saved in the database and how to map them. This context simply exposes the entities and describes the relationship between the Blog and Post entities. This uses the Microsoft.EntityFrameworkCore namespace.

public class BlogsContext : DbContext

{

public BlogsContext(DbContextOptions<BlogsContext> options)

: base(options)

{

}

public DbSet<Blog> Blogs { get; set; }

public DbSet<Post> Posts { get; set; }

protected override void OnModelCreating(ModelBuilder modelBuilder)

{

modelBuilder.Entity<Blog>()

.HasMany(b => b.Posts)

.WithOne(p => p.Blog);

base.OnModelCreating(modelBuilder);

}

}

A real database needs real data, so here’s some code to seed it with my blog and the blog of a colleague of mine. Feel free to add your own RSS feed URLs as well. The code simply accesses the RSS feeds then populates blogs and posts based on the information in the feed. You’ll need references to System.Net.Http for the web client and System.Xml for the XML processing.

public static class Seeder

{

public static async Task CheckAndSeedAsync(BlogsContext context)

{

if (await context.Database.EnsureCreatedAsync())

{

var client = new HttpClient();

var jeremydoc = await client.GetStringAsync(

"https://blog.jeremylikness.com/blog/index.xml");

context.Blogs.Add(ParseDoc(jeremydoc));

var geekdoc = await client.GetStringAsync(

"https://www.geektrainer.dev/index.xml");

context.Blogs.Add(ParseDoc(geekdoc));

await context.SaveChangesAsync();

}

}

private static Blog ParseDoc(string doc)

{

var xmlDoc = new XmlDocument();

xmlDoc.LoadXml(doc);

var channel = xmlDoc.SelectSingleNode("//channel");

var blog = new Blog

{

Id = 0,

Name = channel.SelectSingleNode("title").InnerText,

Url = channel.SelectSingleNode("link").InnerText,

Posts = new List<Post>(),

};

var posts = channel.SelectNodes("item");

foreach (XmlElement post in posts)

{

var postItem = new Post

{

Id = 0,

Title = post.SelectSingleNode("title").InnerText,

Posted = DateTime.Parse(

post.SelectSingleNode("pubDate").InnerText),

Blog = blog

};

blog.Posts.Add(postItem);

}

return blog;

}

}

In Startup.cs we need to add the middleware for filtering and sorting, register the DbContext for dependency injection, and call the seeder the first time the database is created. The changes are highlighted below.

public void ConfigureServices(IServiceCollection services)

{

services.AddGraphQLServer()

.AddQueryType<Query>()

.AddFiltering()

.AddSorting()

.AddProjections();

services.AddDbContext<BlogsContext>(

(s, opt) =>

opt.UseSqlite($"Data Source=blogs.sqlite")

.LogTo(Console.WriteLine, new[]

{

DbLoggerCategory.Database.Command.Name

}));

}

public void Configure(

BlogsContext context,

IApplicationBuilder app,

IWebHostEnvironment env)

{

Seeder.CheckAndSeedAsync(context).Wait();

if (env.IsDevelopment())

{

app.UseDeveloperExceptionPage();

}

app.UseRouting();

app.UseEndpoints(endpoints => endpoints.MapGraphQL("/"));

}

The EF Core configuration sets up a local SQLite database and turns on logging so we can see what is happening “under the covers.”

There is just one more step before we refresh the endpoint. The Query is still hard coded to return static values. The following change injects the EF Core DbContext and returns the IQueryable for Blog. The attributes allow HotChocolate to pass the GraphQL filters to EF Core, and automatically extend the schema to support filtering and sorting.

public class Query

{

[UseProjection]

[UseFiltering]

[UseSorting]

public IQueryable<Blog> GetBlogs(

[Service] BlogsContext context)

=> context.Blogs;

}

Putting it all together

Now that everything is wired together, we can craft a more complex query in 🍌🎂🥤. Here is how to write “Show me the blog names in descending order. For each blog, show me the posted date and title of all posts that have ‘Blazor’ in the title with the newest ones first.”

{

blogs(order: {

name: DESC

}) {

name

posts(where: {

title: {

contains: "Blazor"

}

}, order: {

posted: DESC

}) {

posted

title

}

}

}

The result is exactly what we asked for:

{

"data": {

"blogs": [

{

"name": "GeekTrainer",

"posts": []

},

{

"name": "Blogs on Developer for Life",

"posts": [

{

"posted": "2021-05-16T11:20:33.000-07:00",

"title": "Azure Cosmos DB With EF Core on Blazor Server"

},

{

"posted": "2021-04-29T00:32:27.000-07:00",

"title": "Multi-tenancy with EF Core in Blazor Server Apps"

},

{

"posted": "2021-04-12T11:17:52.000-07:00",

"title": "An Easier Blazor Debounce"

},

{

"posted": "2020-09-20T00:04:59.000-07:00",

"title": "Run EF Core Queries on SQL Server From Blazor WebAssembly"

},

{

"posted": "2020-06-20T00:17:06.000-07:00",

"title": "Build an Azure AD Secured Blazor Server Line of Business App"

},

{

"posted": "2020-06-19T00:00:56.000-07:00",

"title": "Build a Blazor WebAssembly LOB App Part 4: Make it Blazor-Friendly"

},

{

"posted": "2020-06-13T02:06:56.000-07:00",

"title": "Build a Blazor WebAssembly Line of Business App Part 3: Query, Delete and Concurrency"

},

{

"posted": "2020-06-13T01:06:56.000-07:00",

"title": "Build a Blazor WebAssembly Line of Business App Part 2: Client and Server"

},

{

"posted": "2020-06-13T00:06:56.000-07:00",

"title": "Build a Blazor WebAssembly Line of Business App Part 1: Intro and Data Access"

},

{

"posted": "2020-05-25T00:00:38.000-07:00",

"title": "Azure AD Secured Serverless Cosmos DB from Blazor WebAssembly"

},

{

"posted": "2020-05-14T00:26:20.000-07:00",

"title": "EF Core and Cosmos DB with Blazor WebAssembly"

},

{

"posted": "2020-01-14T06:03:07.000-08:00",

"title": "Blazor State Management"

}

]

}

]

}

}

That’s not all. Let’s look at the query generated by EF Core:

SELECT "b"."Name", "b"."Id", "t"."Posted", "t"."Title", "t"."Id"

FROM "Blogs" AS "b"

LEFT JOIN (

SELECT "p"."Posted", "p"."Title", "p"."Id", "p"."BlogId"

FROM "Posts" AS "p"

WHERE "p"."Title" IS NOT NULL AND ((@__p_0 = '') OR (instr("p"."Title", @__p_0) > 0))

) AS "t" ON "b"."Id" = "t"."BlogId"

ORDER BY "b"."Name" DESC, "b"."Id", "t"."Posted" DESC, "t"."Id"

The query is shaped exactly like the GraphQL request with only the fields, filters, and sorts that were requested. This is very powerful because it is streamlined all the way to the database (as opposed to pulling down extra data and projecting it in memory).

Conclusion

There are two sides to every story. It turns out the same is true for GraphQL endpoints: the server is great, but the endpoint is pointless unless there is a client to fetch it. That is a tale for another day, but if you’re interested in writing an awesome Blazor client to consume the API we just built, consider using StrawberryShake and check out the getting started tutorial. I hope I’ve been able to share not just what GraphQL is, but when and why it can or should be used and how to get started in .NET. I’m interested in hearing your GraphQL.NET story, so if you have one, why not reply in comments or ping me on Twitter to share?

Regards,