4db provides a simple, easy-to-use NoSQL database engine for C++ projects. Based on SQLite, 4db is file-based and portable. It provides the common things you do with SQL-type data in a simple API. If you want to add basic database functionality to your C++ project, look no further than 4db.

Background

In this article, we will cover the background, interface, and implementation of 4db, a dynamic, file-based NoSQL database for C++ projects.

4db draws its roots from various things called metastrings over the years.

metastrings is survived in .NET by 4db.net in GitHub, but 4db is a new C++ port. It is modern, clean, and portable, and built directly on the SQLite C API. It should serve C++ developers in need of a simple file-based database well.

Interface

Using 4db is best demonstrated with an annotated sample program:

#include "ctxt.h"

#pragma comment(lib, "4db")

#include <stdio.h>

void addCar(fourdb::ctxt& context, int year,

const std::wstring& make, const std::wstring& model);

int main()

{

printf("Opening database...\n");

fourdb::ctxt context("cars.db");

printf("Starting up...\n");

context.drop(L"cars");

printf("Adding cars to database...\n");

addCar(context, 1987, L"Nissan", L"Pathfinder");

addCar(context, 1998, L"Toyota", L"Tacoma");

addCar(context, 2001, L"Nissan", L"Xterra");

printf("Getting cars...\n");

std::vector<fourdb::strnum> oldCarKeys;

auto select =

fourdb::sql::parse

(

L"SELECT value, year, make, model "

L"FROM cars "

L"WHERE year < @year "

L"ORDER BY year ASC"

);

select.addParam(L"@year", 2000);

auto reader = context.execQuery(select);

while (reader->read())

{

oldCarKeys.push_back(reader->getString(0));

printf("%d: %S - %S\n",

static_cast<int>(reader->getDouble(1)),

reader->getString(2).c_str(),

reader->getString(3).c_str());

}

printf("Deleting old cars... (%u)\n", static_cast<unsigned>(oldCarKeys.size()));

context.deleteRows(L"cars", oldCarKeys);

printf("All done.\n");

return 0;

}

void addCar(fourdb::ctxt& context, int year,

const std::wstring& make, const std::wstring& model)

{

std::wstring tableName = L"cars";

fourdb::strnum primaryKey = fourdb::num2str(year) + L"_" + make + L"_" + model;

fourdb::paramap columnData

{

{ L"year", year },

{ L"make", make },

{ L"model", model },

};

context.define(tableName, primaryKey, columnData);

}

Implementation

The metastrings concept was always to present what looks like a rows-and-columns SQL interface with an implementation in a "real" SQL database, initially only MySQL, now only SQLite.

The "virtual" schema's tables are pulled into separate real tables in SQLite:

- A registry of all tables in the virtual schema is stored in the real tables, um, table

- All columns in all tables are in the names table

- Every unique value in the entire database -

wstring or double - is stored in the values table - Each row in each virtual table is represented by a row in the real items table

- Everything is glued together by the itemnamevalues table, one row per data cell,

itemid -> nameid -> valueid

Tons of overhead, will probably never have high performance. But it's simple, and allows for a dynamic schema. And there are tons of use cases where high performance isn't a requirement. I see a bright future for this technology.

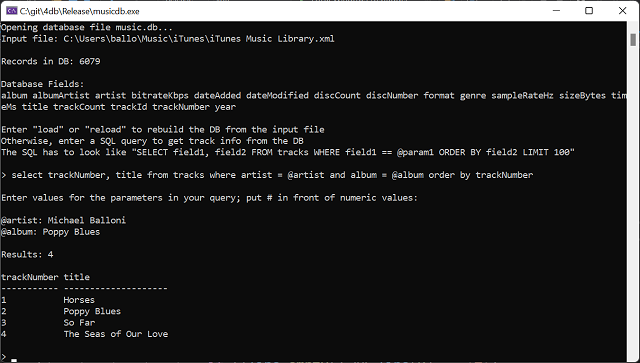

musicdb - A Larger Example

iTunes, on Windows at least, has a file describing the media library in an easily parsed XML file. There is an entry in this file for each track in the library. Each entry looks like this in the XML file:

<dict>

<key>Track ID</key><integer>1002</integer>

<key>Size</key><integer>7973544</integer>

<key>Total Time</key><integer>242755</integer>

<key>Disc Number</key><integer>1</integer>

<key>Disc Count</key><integer>1</integer>

<key>Track Number</key><integer>1</integer>

<key>Track Count</key><integer>13</integer>

<key>Year</key><integer>2012</integer>

<key>Date Modified</key><date>2016-08-22T01:35:10Z</date>

<key>Date Added</key><date>2021-03-17T00:41:46Z</date>

<key>Bit Rate</key><integer>256</integer>

<key>Sample Rate</key><integer>44100</integer>

<key>Artwork Count</key><integer>1</integer>

<key>Persistent ID</key><string>A8CF63F61390C4BC</string>

<key>Track Type</key><string>File</string>

<key>File Folder Count</key><integer>5</integer>

<key>Library Folder Count</key><integer>1</integer>

<key>Name</key><string>Kryptonite</string>

<key>Artist</key><string>3 Doors Down</string>

<key>Album Artist</key><string>3 Doors Down</string>

<key>Composer</key><string>Matt Roberts</string>

<key>Album</key><string>The Greatest Hits [+digital booklet]</string>

<key>Genre</key><string>Alternative Rock</string>

<key>Kind</key><string>MPEG audio file</string>

<key>Comments</key><string>Amazon.com Song ID: 233359329</string>

<key>Sort Album</key><string>Greatest Hits [+digital booklet]</string>

<key>Location</key><string>file://localhost/C:/Users/ballo/Music/iTunes/iTunes%20Media/

Music/3%20Doors%20Down/The%20Greatest%20Hits%20%5B+digital%20booklet%5D/

01-01-%20Kryptonite.mp3</string>

</dict>

The musicdb program parses the entire XML file and builds an in-memory representation of the library. It makes a single 4db call to load that representation into the 4db database:

bool inDict = false;

std::unordered_map<fourdb::strnum, fourdb::paramap> dicts; fourdb::paramap dict; ...

while (xmlFileStream)

{

std::wstring line;

std::getline(xmlFileStream, line);

const wchar_t* tag = wcsstr(line.c_str(), L"<");

if (tag == nullptr)

continue;

if (_wcsicmp(tag, L"<dict>") == 0)

{

inDict = true;

dict.clear();

}

else if (_wcsicmp(tag, L"</dict>") == 0)

{

inDict = false;

if (dict.size() == 1)

continue;

std::wstring key; for (const auto& kvp : dict)

{

const auto& snum = kvp.second;

if (snum.isStr())

key += snum.str();

else

key += fourdb::num2str(snum.num());

key += '|';

}

dicts.insert({ key, dict });

++addedCount;

}

else if (inDict && wcsncmp(tag, L"<key>", 5) == 0) {

const wchar_t* closingKey = wcsstr(tag, L"</key>");

if (closingKey == nullptr)

{

printf("Unclosed <key>: %S\n", line.c_str());

continue;

}

std::wstring key(tag + 5, closingKey);

cleanXmlValue(key);

const auto& fieldNameIt = fieldNames.find(key); if (fieldNameIt == fieldNames.end())

continue; const auto& fieldName = fieldNameIt->second;

const wchar_t* valueTag = nullptr;

valueTag = wcsstr(closingKey, L"<integer>");

if (valueTag != nullptr)

{

const wchar_t* closingValue = wcsstr(tag, L"</integer>");

if (closingValue == nullptr)

{

#ifdef _DEBUG

printf("Unclosed <integer>: %S\n", line.c_str());

#endif

continue;

}

std::wstring valueStr(valueTag + 9, closingValue);

double valueNum = _wtof(valueStr.c_str());

dict.insert({ fieldName, valueNum });

continue;

}

valueTag = wcsstr(closingKey, L"<string>");

if (valueTag != nullptr)

{

const wchar_t* closingValue = wcsstr(tag, L"</string>");

if (closingValue == nullptr)

{

#ifdef _DEBUG

printf("Unclosed <string>: %S\n", line.c_str());

#endif

continue;

}

std::wstring valueStr(valueTag + 8, closingValue);

cleanXmlValue(valueStr);

dict.insert({ fieldName, valueStr });

}

valueTag = wcsstr(closingKey, L"<date>");

... }

...

}

context.define(L"tracks", dicts, [](const wchar_t* msg) { printf("%S...\n", msg); });

Once the 4db database is populated, you can query it using a basic dialect of SQL SELECT statements, and get query results in a pleasant format:

printf("> ");

std::wstring line;

std::getline(std::wcin, line);

...

auto select = fourdb::sql::parse(line);

auto paramNames = fourdb::extractParamNames(line);

if (!paramNames.empty())

{

printf("\n");

printf("Enter values for the parameters in your query;"

" put # in front of numeric values:\n");

printf("\n");

for (const auto& paramName : paramNames)

{

printf("%S: ", paramName.c_str());

std::getline(std::wcin, line);

if (!line.empty() && line[0] == '#')

select.addParam(paramName, _wtof(line.substr(1).c_str()));

else

select.addParam(paramName, line);

}

}

auto reader = context.execQuery(select);

auto colCount = reader->getColCount();

std::vector<std::vector<std::wstring>> matrix;

std::unordered_set<std::wstring> seenRowSummaries;

while (reader->read())

{

std::vector<std::wstring> newRow;

for (unsigned col = 0; col < colCount; ++col)

newRow.push_back(reader->getString(col));

std::wstring newRowSummary = fourdb::join(newRow, L"\v");

if (seenRowSummaries.find(newRowSummary) != seenRowSummaries.end())

continue;

seenRowSummaries.insert(newRowSummary);

matrix.push_back(newRow);

}

printf("\n");

printf("Results: %u\n", static_cast<unsigned>(matrix.size()));

if (matrix.empty())

continue;

printf("\n");

std::vector<std::wstring> headerRow;

for (unsigned col = 0; col < colCount; ++col)

headerRow.push_back(reader->getColName(col));

matrix.insert(matrix.begin(), headerRow);

std::vector<unsigned> columnWidths;

for (const auto& header : headerRow)

columnWidths.push_back(static_cast<unsigned>(header.size()));

for (const auto& row : matrix)

{

for (size_t cellidx = 0; cellidx < columnWidths.size(); ++cellidx)

columnWidths[cellidx] = std::max(columnWidths[cellidx], row[cellidx].size());

}

for (size_t cellidx = 0; cellidx < columnWidths.size(); ++cellidx)

{

const auto& header = headerRow[cellidx];

auto headerWidth = columnWidths[cellidx];

printf("%S", header.c_str());

for (size_t s = header.size(); s <= headerWidth; ++s)

printf(" ");

}

printf("\n");

for (size_t cellIdx = 0; cellIdx < columnWidths.size(); ++cellIdx)

{

auto headerWidth = columnWidths[cellIdx];

for (size_t s = 0; s < headerWidth; ++s)

printf("-");

printf(" ");

}

printf("\n");

for (size_t rowIdx = 1; rowIdx < matrix.size(); ++rowIdx)

{

const auto& row = matrix[rowIdx];

for (size_t cellIdx = 0; cellIdx < columnWidths.size(); ++cellIdx)

{

const auto& value = row[cellIdx];

auto headerWidth = columnWidths[cellIdx];

printf("%S", value.c_str());

for (size_t s = value.size(); s <= headerWidth; ++s)

printf(" ");

}

printf("\n");

}

SQLite Wrapper

Central to 4db are wrapper classes around SQLite's C API. The db class manages the database connection and provides routines for executing queries. The dbreader class prepares and executes queries and provides access to query results.

Parameters are passed in using a paramap, which is a typedef of std::unordered_map<std::wstring, strnum>. strnum is a class that is either a wstring or a double.

It was fun learning about SQLite's C API. The wrapper classes mostly stand on their own; you can mold them to your purposes with little work.

Conclusion

I hope you've enjoyed learning about 4db, and seeing how fun processing your iTunes media library can be with 4db.

History

- 22nd November, 2021: Initial version