Holistic example of clean architecture in Go, covering development, documenting, and deploying of a web API

Introduction

A lot has been written about the clean architecture. Its main value is the ability to maintain free from side effects domain layer that allows us to test core business logic without leveraging heavy mocks.

This is accomplished by writing dependency-free core domain logic and external adapters (be it database storage or API layer) that rely on the domain and not vice versa.

In this article, we’ll have a look at how clean architecture is implemented with a sample Go project. We’ll cover some additional topics such as containerization and implementing OpenAPI specification with Swagger.

While I’ll highlight the points of interest in the article, you may take a look at the entire project at my Github.

Project Requirements

We are required to provide an implementation of a REST API to simulate a deck of cards.

We will need to provide the following methods to your API to handle cards and decks:

- Create a new

Deck - Open a

Deck - Draw a

Card

Create a New Deck

It would create the standard 52-card deck of French playing cards, It includes all thirteen ranks in each of the four suits: clubs (♣), diamonds (♦), hearts (♥) and spades (♠). You don’t need to worry about Joker cards for this assignment.

- the deck to be shuffled or not — by default, the deck is sequential: A-spades, 2-spades, 3-spades… followed by diamonds, clubs, then hearts.

- the deck to be full or partial — by default, it returns the standard 52 cards, otherwise the request would accept the wanted cards like this example

?cards=AS,KD,AC,2C,KH

The response needs to return a JSON that would include:

- the deck id (UUID)

- the deck properties like shuffled (boolean) and total cards remaining in this deck (integer)

{

"deck_id": "a251071b-662f-44b6-ba11-e24863039c59",

"shuffled": false,

"remaining": 30

}

Open a Deck

It would return a given deck by its UUID. If the deck was not passed over or is invalid, it should return an error. This method will “open the deck”, meaning that it will list all cards by the order it was created.

The response needs to return a JSON that would include: - the deck id (UUID) - the deck properties like shuffled (boolean) and total cards remaining in this deck (integer) - all the remaining cards cards (card object).

{

"deck_id": "a251071b-662f-44b6-ba11-e24863039c59",

"shuffled": false,

"remaining": 3,

"cards": [

{

"value": "ACE",

"suit": "SPADES",

"code": "AS"

},

{

"value": "KING",

"suit": "HEARTS",

"code": "KH"

},

{

"value": "8",

"suit": "CLUBS",

"code": "8C"

}

]

}

Draw a Card

We would draw a card(s) of a given Deck. If the deck was not passed over or invalid, it should return an error. A count parameter needs to be provided to define how many cards to draw from the deck.

The response needs to return a JSON that would include: all the drawn cards cards (card object):

{

"cards": [

{

"value": "QUEEN",

"suit": "HEARTS",

"code": "QH"

},

{

"value": "4",

"suit": "DIAMONDS",

"code": "4D"

}

]

}

Designing the Domain

Since the domain is an integral part of our application, we’ll start designing our system from the domain.

Let’s encode our Shape and Rank types as iota. If you’re acquainted with other languages, you might think of it as an enum which is pretty neat since our task assumes some sort of build-in order so we might leverage underlying numerical value just for that matter.

type Shape uint8

const (

Spades Shape = iota

Diamonds

Clubs

Hearts

)

type Rank int8

const (

Ace Rank = iota

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Jack

Queen

King

)

With that done, we can encode Card as a combination of its shape and rank.

type Card struct {

Rank Rank

Shape Shape

}

One of the functions of domain-driven design is making illegal states unrepresentable but since all combinations of ranks and shapes are valid, creating a card is pretty straightforward.

func CreateCard(rank Rank, shape Shape) Card {

return Card{

Rank: rank,

Shape: shape,

}

}

Now let’s have a look at the Deck:

type Deck struct {

DeckId uuid.UUID

Shuffled bool

Cards []Card

}

The Deck will exhibit three operations: create a deck, draw cards and count remaining cards.

func CreateDeck(shuffled bool, cards ...Card) Deck {

if len(cards) == 0 {

cards = initCards()

}

if shuffled {

shuffleCards(cards)

}

return Deck{

DeckId: uuid.New(),

Shuffled: shuffled,

Cards: cards,

}

}

func DrawCards(deck *Deck, count uint8) ([]Card, error) {

if count > CountRemainingCards(*deck) {

return nil, errors.New("DrawCards: Insufficient amount of cards in deck")

}

result := deck.Cards[:count]

deck.Cards = deck.Cards[count:]

return result, nil

}

func CountRemainingCards(d Deck) uint8 {

return uint8(len(d.Cards))

}

Notice that when drawing cards, we check whether we have a sufficient amount of cards to perform the operation. In order to signal in case we’re unable to proceed, we take advantage of Go multiple return values feature.

At this point, we may observe one of the key benefits of clean architecture: the core domain logic has no external dependencies which greatly simplifies unit-testing. While most of them are trivial and we’ll omit them for the sake of brevity, let’s have a look at those that verify whether the deck is shuffled.

func TestCreateDeck_ExactCardsArePassed_Shuffled(t *testing.T) {

jackOfDiamonds := CreateCard(Jack, Diamonds)

aceOfSpades := CreateCard(Ace, Spades)

queenOfHearts := CreateCard(Queen, Hearts)

cards := []Card{jackOfDiamonds, aceOfSpades, queenOfHearts}

deck := CreateDeck(false, cards...)

deckCardsCount := make(map[Card]int)

for _, resCard := range deck.Cards {

value, exists := deckCardsCount[resCard]

if exists {

value++

deckCardsCount[resCard] = value

} else {

deckCardsCount[resCard] = 1

}

}

for _, inputCard := range cards {

value, found := deckCardsCount[inputCard]

assert.True(t, found, "Expected all cards to be present")

assert.Equal(t, 1, value, "Expected cards not to be duplicate")

}

}

Obviously, we cannot verify the order of shuffled cards. What we can do instead is to verify that the shuffled deck satisfies properties of interest which are that we have every card present and we have no duplicate cards in our deck. Such a technique closely resembles property-based testing.

As a side note, it’s worth mentioning that in order to eliminate boilerplate assertion code, we take advantage of testify library.

Providing the API

Let’s start off with defining routes.

func main() {

r := gin.Default()

r.POST("/create-deck", api.CreateDeckHandler)

r.GET("/open-deck", api.OpenDeckHandler)

r.PUT("/draw-cards", api.DrawCardsHandler)

r.Run()

}

Some of the readers may be confused by the fact that the create-deck endpoint according to the requirements listed above accepts parameters as a part of URL request and might consider making this endpoint accept GET requests instead of POST. However, an important prerequisite of GET requests is that they exhibit idempotency which is not the case for this endpoint. This is the exact reason why we stick with POST.

Handlers follow the same patterns. We parse query parameters, based on them we create a domain entity, perform operations upon it, update the storage and return specialized DTO. Let’s have a look at more details.

type CreateDeckArgs struct {

Shuffled bool `form:"shuffled"`

Cards string `form:"cards"`

}

type OpenDeckArgs struct {

DeckId string `form:"deck_id"`

}

type DrawCardsArgs struct {

DeckId string `form:"deck_id"`

Count uint8 `form:"count"`

}

func CreateDeckHandler(c *gin.Context) {

var args CreateDeckArgs

if c.ShouldBind(&args) == nil {

var domainCards []domain.Card

if args.Cards != "" {

for _, card := range strings.Split(args.Cards, ",") {

domainCard, err := parseCardStringCode(card)

if err == nil {

domainCards = append(domainCards, domainCard)

} else {

c.String(400, "Invalid request. Invalid card code "+card)

return

}

}

}

deck := domain.CreateDeck(args.Shuffled, domainCards...)

storage.Add(deck)

dto := createClosedDeckDTO(deck)

c.JSON(200, dto)

return

} else {

c.String(400, "Ivalid request.

Expecting query of type ?shuffled=<bool>&cards=<card1>,<card2>,...<cardn>")

return

}

}

func OpenDeckHandler(c *gin.Context) {

var args OpenDeckArgs

if c.ShouldBind(&args) == nil {

deckId, err := uuid.Parse(args.DeckId)

if err != nil {

c.String(400, "Bad Request. Expecing request in format ?deck_id=<uuid>")

return

}

deck, found := storage.Get(deckId)

if !found {

c.String(400, "Bad Request. Deck with given id not found")

return

}

dto := createOpenDeckDTO(deck)

c.JSON(200, dto)

return

} else {

c.String(400, "Bad Request. Expecing request in format ?deck_id=<uuid>")

return

}

}

func DrawCardsHandler(c *gin.Context) {

var args DrawCardsArgs

if c.ShouldBind(&args) == nil {

deckId, err := uuid.Parse(args.DeckId)

if err != nil {

c.String(400, "Bad Request. Expecing request in format ?deck_id=<uuid>")

return

}

deck, found := storage.Get(deckId)

if !found {

c.String(400, "Bad Request.

Expecting request in format ?deck_id=<uuid>&count=<uint8>")

return

}

cards, err := domain.DrawCards(&deck, args.Count)

if err != nil {

c.String(400, "Bad Request. Failed to draw cards from the deck")

return

}

var dto []CardDTO

for _, card := range cards {

dto = append(dto, createCardDTO(card))

}

storage.Add(deck)

c.JSON(200, dto)

return

} else {

c.String(400, "Bad Request.

Expecting request in format ?deck_id=<uuid>&count=<uint8>")

return

}

}

Logging

One of the important aspects of running software is the ability to figure out the current state of the software. Writing logs helps in that matter so we’ll add some to our code.

What to log

It is important to find a balance between writing too few logs and being too verbose and polluting log storage with excessive noisy messages. In our project, we’ll follow this advice and will treat logs as events on a service boundary. In our case, such events occur inside a domain layer when making operations with a deck. Additionally, we’ll log incoming requests on the API level to see which requests are coming in. If we’ve used real storage, it would be nice to log queries generated with the debug severity but since using real storage is outside the scope of our article, we’ll omit that.

Logging Domain Events

For logging purpose, we’ll use zap since it has logging levels, supports structured logging, and shows good results on benchmarks. With that said, let’s do some logging.

func CreateDeck(shuffled bool, cards ...Card) Deck {

logger, _ := zap.NewProduction()

defer logger.Sync()

sugar := logger.Sugar()

sugar.Infow("Create deck.", "shuffled", shuffled, "cards", cards)

sugar.Infow("Create deck completed", "deck", result)

return result

}

func DrawCards(deck *Deck, count uint8) ([]Card, error) {

logger, _ := zap.NewProduction()

defer logger.Sync()

sugar := logger.Sugar()

sugar.Infow("Draw cards.", "deck", deck, "count", count)

sugar.Infow("Draw cards completed.", "result", result, "deck", deck)

return result, nil

}

The code above is pretty straightforward. We’re creating a logger using a predefined configuration. Then we defer flushing the logger. Calling Sugar method allows us to accept loosely typed logging with a variadic number of arguments. Then we call Infow method to write a log message with Info severity.

Logging API

Gin framework provides logging by default but since we want to support structured logging, we’ll define custom logging middleware that mimics Gin built-in logging.

func StructuredLogger() gin.HandlerFunc {

return func(c *gin.Context) {

logger, _ := zap.NewProduction()

defer logger.Sync()

sugar := logger.Sugar()

start := time.Now()

c.Next()

stop := time.Now()

latency := stop.Sub(start)

if c.Writer.Status() >= 500 {

sugar.Errorw("error", c.Errors.ByType(gin.ErrorTypePrivate).String(),

"IP", c.ClientIP(),

"method", c.Request.Method,

"status", c.Writer.Status(),

"size", c.Writer.Size(),

"path", c.Request.URL.Path,

"latency", latency)

} else {

sugar.Infow("request",

"IP", c.ClientIP(),

"method", c.Request.Method,

"status", c.Writer.Status(),

"size", c.Writer.Size(),

"path", c.Request.URL.Path,

"latency", latency)

}

}

}

Here, depending on the result, we employ different logging levels.

We register our middleware below:

r := gin.New()

r.Use(api.StructuredLogger())

r.Use(gin.Recovery())

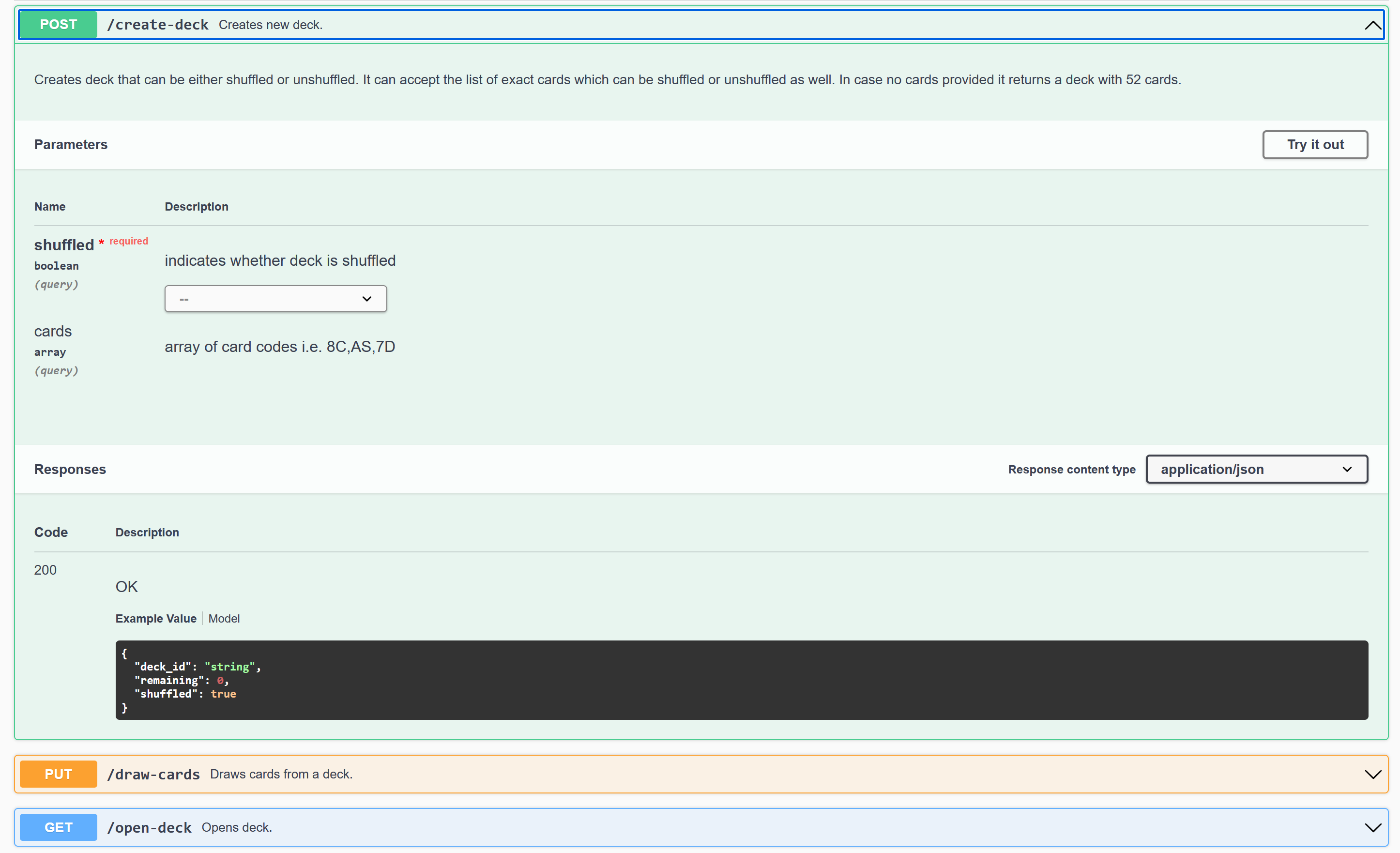

Defining OpenAPI Specification

The way we should treat OpenAPI specification is not solely as a fancy docs generator (although it is sufficient for the sake of our article) but also as a standard for describing REST APIs that simplifies their consumption for the clients.

Let’s start off with declarative comments decorating our main method. These comments will be used later to automatically generate Swagger Specification. Here, you can look up the format.

func main() {

The same goes for our handler. Let’s take a look at one of them as an example.

func CreateDeckHandler(c *gin.Context) {

Now let’s pull Swagger libraries.

go get -v github.com/swaggo/swag/cmd/swag

go get -v github.com/swaggo/gin-sagger

go get -v github.com/swaggo/files

Now we’re going to generate the specification:

swag init -g main.go --output docs

This command will generate needed files inside the docs folder.

The next step is updating our main.go file with the necessary imports:

_ "toggl-deck-management-api/docs"

swaggerFiles "github.com/swaggo/files"

ginSwagger "github.com/swaggo/gin-swagger"

And the endpoint:

url := ginSwagger.URL("/swagger/doc.json")

r.GET("/swagger/*any", ginSwagger.WrapHandler(swaggerFiles.Handler, url))

With all that done, now we can run our application and see documentation generated by Swagger.

Containerizing API

Last but not least is how we are going to deploy our application. The traditional way of doing this is installing the runtime on a dedicated server and running the application over the runtime installed.

Containerization is the convenient way to package runtime along with the application which might be convenient if we want to utilize auto-scale functionality and we might not have all the needed servers with the environment installed at our disposal.

Docker is the most popular containerization solution so we’ll take advantage of it. To do so, we’ll create dockerfile at the root of our project.

The first thing we’ll do is choose the runtime image we’ll base our application upon:

FROM golang:1.18-bullseye

After that, we’ll copy the source into the work directory and build it:

RUN mkdir /app

COPY . /app

WORKDIR /app

RUN go build -o server .

The last step is exposing the port to the outside world and running the application:

EXPOSE 8080

CMD [ "/app/server" ]

Now, granted Docker is installed on our machine, we can run the app with:

docker build -t <image-name> .

docker run -it --rm -p 8080:8080 <image-name>

Conclusion

In this article, we’ve covered the holistic process of writing clean architecture API in Go. Starting from the well-tested domain, providing an API layer for it, documenting it using OpenAPI standard, and packaging our runtime together with the app and thus simplifying the deployment process.

History

- 21st November, 2022 - Published initial version

- 25th May, 2023 - Added logging section