George's Getting Started with Node.js Series

Introduction

Welcome to what I hope to be a long series of articles on learning and using Node.js. The plan (work and children permitting) is to produce an article twice a month.

This series of articles is in the format of "Learn Along With Me". What does that mean? I'm new to Node.js, as fresh as they come. I've got extensive experience in other technologies, but when it comes to Node... not so much. I've set up a project containing several sprints to get my head around this technology and I thought it would be fun to write an article as each sprint was completed.

I am by no means an expert, I'm sure I'll make mistakes or go against best practices several times. I'm hoping by the end of my little project, I (and you) will attain at least an intermediate level of expertise with Node, but I want to be absolutely clear up front: I am not an expert, don't pretend to be, and you shouldn't take this series as something coming from one.

A Note on Frameworks

I'm well aware that are innumerable frameworks that do a lot (if not all) of what I'm going to be doing in this series. I don't suffer from the "Not Invented Here" syndrome, I am purposely eschewing using frameworks until I have a firmer understanding of the underlying environment, and there is no better way of doing that (in my opinion) than doing things the hard way. I love frameworks, I love being able to leverage previous work and to "Just get the job done", but again, when learning I like to make my own mistakes... I find it helps me gain a more robust core of knowledge.

Sprint 1 Items

The initial sprint (the focus of this article) is relatively simple. I want to:

- Be able to create an HTTP server

- Determine the IP of the incoming request

- Create custom modules

- Create a standard response module

- Serialize objects to JSON

- Serialize objects to XML

- Capture Querystring data

- Capture POST Data

- Respond to the request in some meaningful way

So let's get started!

Node.js

Node.js is a server side implementation of the Google V8 JavaScript engine. You can find in depth information about Node.js at http://nodejs.org. Every article I've ever read about Node wastes far too much space on describing node and they all quote information from that site, so if you don't mind, I'll just point you there.

Environment

This series of articles is currently targeting Node v.0.10.22.

Node can be installed on Windows, Linux and Macintosh. My personal setup is a combination of a CentOS VM with node installed, and a Windows box with Node installed. You can work with node via SSH and VI on your Linux box or you can install the Visual Studio extension for Node from Microsoft. I know I'm probably going to anger many a purist when I say that I hate VI, the Node extension is wonderful I highly recommend it. I write my Node code in Visual Studio then ship it over to the CentOS box to run. It works for me.

Modules

Modules in Node are a way to separate your code into logical sections and use them at need. Node (as they describe it) has a simple module loading system using the requires keyword. For this first article, we'll be creating three custom modules to fulfill the requirements of the first sprint.

The FieldParser Module

The FieldParser module handles parsing POST and GET data from the request object. For Query String data, this is fairly simple as it comes over in one shot, however, POST data comes over chunked, so we'll have to handle that and raise an event when parsing is done.

To handle events, we'll have to inherit from the EventEmitter class. You can do this manually, or you can use the inherits method from the native node module util.

The FieldParser module is the only module that will be concerned with events for this first article and will export a FieldParser object using the module.exports method.

The FieldParser has the following methods / properties.

method: the method detected from the request, either POST, GET, or GETPOST (Both querystring and post data sent)fields: collection of parsed fields queryFields: collection of parse Query String fields (NO post fields)fieldCount: the number of fields parsed

When the method is POST the fields collection will contain all the posted fields and the queryFields collection will be empty.

When the method is GET the fields AND the queryFields collection will be populated with the same data

When the method is GETPOST (both Query String and POST data submitted) the fields collection will contain the POSTed fields and the queryFields collection will contain the query string parsed fields.

Parsing will begin when the parse method is called, and the object will indicate that parsing is completed when it raises the event "parsed".

The code for the

FieldParser module can be found in the attached zip file under the /modules directory

The XMLSerializer Module

The XMLSerializer module handles serializing a JavaScript object to XML. It's fairly basic and probably (definitely) needs to be worked on, but for a first version, and for the purposes of fulfilling sprint 1 requirements I think it works well.

The XMLSerializer module exports a single method: serialize(name, obj, encoding). This method takes in three parameters.

- The

name of the object (string) to be used as the parent node tag name for the serialized output (required). - The object to be serialized itself (

obj) (required) - The

encoding for the XML output (utf-8, utf-16, us-ascii, etc)

The serialize method will return a string representing the serialized object. This is immediate and no event is raised to indicate it is done (unlike the FieldParser module)

The code for the XMLSerializer module can be found in the attached zip file under the /modules directory.

The SerialResponse Module

The SerialResponse module is a module for handling sending a standardized serialized response back to the requesting client. I wanted something that could contain a standard status return as well as the serialized object payload. Therefor the SerialResponse module exposes the following:

XMLResponse(res, code, payload, what) method. which writes out a serialized XML object to response. this method takes in the parameters:

res : the response object to write to code: the numeric code for the ResponseCode status objectpayload: the payload object to be serializedwhat: a string description of the payload object

This method writes the header to the response, and ends the response. when you just want to write to the response object without writing the header and ending the response use the method XMLResponseWrite which takes in the same parameters but does not write the response header or end (close) the response. JSON Response(res, code, payload, what) method. Which writes out a serialized JSON object to response. This method takes in the parameters:

res: the response object to write to code: the numeric code for the ResponseCode status object payload: the payload object to be serialized what: a string description of the payload object

This method writes the header to the response, and ends the response. when you just want to write to the response object without writing the header and ending the response use the method JSONResponseWrite which takes in the same parameters but does not write the response header or end (close) the response.setCode(code, description, level) This method adds or sets the value in the codeDictionary collection of the SerialResponse module. there are two standard ResponseCodes 0 and 1. 0 = OK and has the level of "OK", 1 = Invalid Response Code Passed and has the level of "WARN". You can think of Response Codes as exit codes if you wish. That's the concept I'll be using them for in follow on articles.dictionary: This method simply returns the codeDictionary if you want to see what's in it.

Any time we use the SerialResponse methods XMLResponse, XMLResponseWrite, JSONResponse, or JSONResponseWrite it will output a string representing a serialized object that is part of an overall serialized object that contains the following:

- -

status : a status code object (independant of the http response code) that returns a numeric code, a description, and a response level indicating the status of the returned object. recommended levels are "OK", "WARN", and "ERROR". adding custom codes to the codeDictionary can be accomplished using the setCode method. - -

what: a string description of what the payload object is. - -

payload: the serialized object you're returning to the requesting client.

NOTE: The SerialResponse module is dependant upon the XMLSerializer module.

The code for the SerialResponse module can be found in the attached zip file under the /modules directory.

Using the Code

Ok, now that we've spent so much time describing the custom modules for this application (and I do hope you've looked through the code attached), let's go ahead and put it all together into a basic Node.js server application that takes in some input from the client and repeats it back to us. In later articles, we'll explore actually using this data for something besides proof of concept. But for now, the purpose of this exercise was to be able to fulfill the requirements of sprint 1.

Importing the modules we'll need.

This app will need three modules.

- The

http module where http handling resides in the node world (which will give us the ability to create our listener / server. - The

FieldParser module where we can parse out the get and post data sent in - Finally, the

SerialResponse module where we can have our standard response handling.

NOTE: The FieldParser and SerialResponse modules are custom modules we wrote ourselves and they're in the /modules directory, so when we require() (import) them we'll have to describe their path with a prefix of ./modules/

var http = require("http");

var fieldparser = require("./modules/FieldParser.js");

var serializedresponse = require("./modules/SerialResponse.js"); Letting ourselves know the server has started.

console.log("Server Started"); Creating the server itself

We're going to create the server as a variable that listens for a request and response. we'll set the actual listen up after we create the server variable. This is where we'll get the data submitted, parse it, and respond back out. Note that we do so using events. The parser is asynchronous and the only way we'll know parsing is complete is to wait for the parsed event to be raised. (All of node.js is asynchronous it seems. They call it non-blocking, but I'm not entirely sure of the full ramifications of this yet.)

var server = http.createServer(function(req, res) {

console.log("Received Request From : " + req.connection.remoteAddress);

fp.parse(req);

fp.on("parsed", function() {

serializedresponse.XMLResponse(res, 0, fp, "parsed fields");

})

});Setting the server to listen on port 3000

If we don't set the server to listen on a particular port (in this case 3000), then node will drop out and terminate. This happens because node only runs so long as there is something to be done... like listening for a request. If there is nothing to do, the application terminates and you're done.

server.listen(3000);

Testing (Playing with It)

At this point, you need to run your Node application. You can either do so from the command line by typing "node app.js" in the directory you've put all the attached files in, or if you're using the VisualStudio node extension hit "F5" to run.

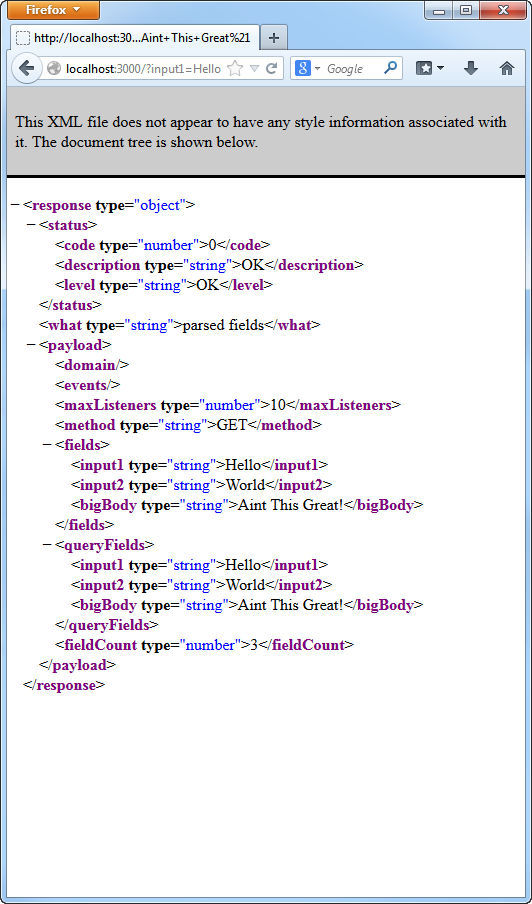

I've included a small test.html file in the zip package that allows you to post data to your new server. Let's say you use the "GET" form in the test.html file and submit in field one: "Hello" and in field two "World" and in the text area "Aint this Great", you should have a response that looks something like...

From here on, I suggest you play with the attached code, try out JSONResponse or JSONResponseWrite. I look forward to your feedback.

I had to trim this article down a lot, several times, but I hope it was helpful as is.