Introduction

This article gives an overview of Xamarin.Android, which is a MonoDroid plug-in for Visual Studio. It allows .NET developers to build applications that target the Android platform using their existing IDE and language, therefore without having to learn Java / Eclipse. The article will go through the basics of creating a Xamarin.Android project as well explaining the key elements and project structure.

Background

Xamarin are a California based software company who created Mono, MonoTouch and Mono for Android which are all cross-platform implementations of the Common Language Infrastructure (CLI) and Common Language Specifications (which are often referred to as Microsoft.NET)

Extracted from Visual Studio Magazine

"Monodroid is a plug-in to Visual Studio 2010. This plug-in allows developers to deploy apps to the Android Emulator running locally, as well as to a physical device connected over a USB cable and Wi-Fi. The plug-in allows MonoDroid to actively work with the rest of the Visual Studio ecosystem and integrate with the tools that developers are already using."

Using the C# language, developers are able to build native apps that can target iOS, Android and Windows Phone. They can use either Xamarin Studio (which is an IDE that is downloaded as part of the Xamarin.Android SDK) or they can use Visual Studio. Personally, I use Visual Studio as that is what I am most familiar with. For the purposes of this article, I will use Visual Studio.

This article assumes the reader is familiar with C#, Visual Studio and the .NET Framework. It also assumes that you have downloaded the Xamarin.Android SDK from the Xamarin web site. if you haven't then download it now.

Creating your First Xamarin.Android Project

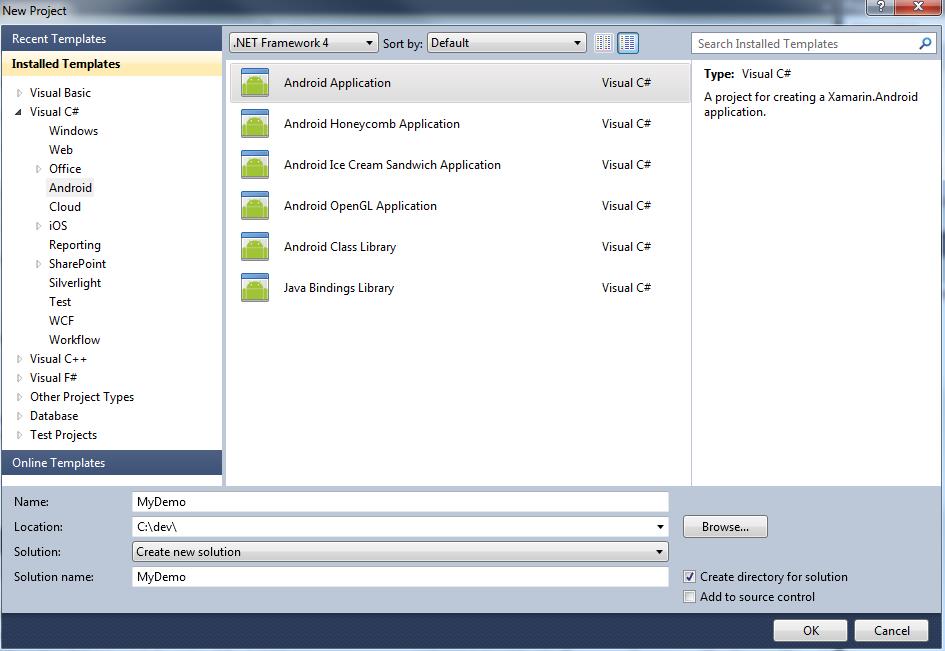

To create your first Xamarin.Android project, open Visual Studio and select File -> New -> Project. In the list of installed templates on the left, select Visual C#. Underneath this, you should see Android. When selecting this, you should see a list of Xamarin.Android project templates similar to those shown in the screenshot below.

As you can see, there are several installed Xamarin.Android project templates. For the purposes of this article, I will use the Android Application template. Give your project a meaningful name (I have named mine MyDemo but feel free to name yours whatever you like). Click OK to continue to create your project.

Project Structure

When your project has been created, you will see the following project structure.

Expand the Resources folder and its sub-folders as in the screenshot below:

Let's go through the various parts of the project one at a time and explain what they are and what they do. I won't go into the standard .NET elements, but instead focus on those that are specific to Xamarin.Android.

Activity1.cs - This is the default Android Activity that is created. An Activity is an Android specific entity. They define a single, focused thing that the user can perform such as adding a new customer, viewing a list of goods and so on. They have their own lifecycle and events. They are key to an Android application and so it is important to understand them.

Expand the Properties folder.

- AndroidManifest.xml - This file defines essential information about the application to the Android system. Every Android application has one of these. This file MUST be present for the application to run as it defines such things as the name of the application to the Android system, describes the components of the application, declares permissions and defines the minimum Android API level for example.

Expand the Resources folder.

- Drawable - This folder contains the images for your application. If your application requires different sized images for the different screen sizes, then create a sub-folder underneath here for each of the different resolutions.

- Layout - This folder contains the Android layout (.AXML) files for your project. An Android layout file is similar to an HTML or ASPX file. It defines a single Android screen using XML syntax. Create a new layout for each screen. If your application requires different layouts for landscape or portrait, then you need to create layout-land and layout-port sub-folders respectively. By default, there is a layout created automatically for you called Main.axml. This is the UI layout that is invoked by the default

Activity class mentioned earlier - Activity1.cs. - Values - This folder contains resource definitions that your application uses such as

string values. For example, you could store the name of the application or dropdown list items in the Strings.xml file - Resource.Designer.cs - This file contains the class definitions for the generated IDs contained within the application. This allows application resources to be retrieved by name so the developer does not have to use the ID. The file therefore maps the application resource name to its generated ID. The file is updated each time the project is built. This file should NOT be updated by the developer.

Other files you could have underneath the Values folder include:

- Arrays.xml

- Colors.xml

- Dimensions.xml

- Styles.xml

The default entries for Strings.xml are listed below:

="1.0"="utf-8"

<resources>

<string name="Hello">Hello World, Click Me!</string>

<string name="ApplicationName">MyDemo</string>

</resources>

To use a Strings.xml entry from an Android layout (.AXML) file.

<TextView

android:text="@string/ApplicationName"

android:id="@+id/txtApplicationName" />

To use a Strings.xml entry from your application code.

string applicationName = GetString(Resource.String.ApplicationName);

An example entry for Arrays.xml:

="1.0"="utf-8"

<resources>

<string-array name="payment_types">

<item>Cash</item>

<item>Debit Card</item>

<item>Credit Card</item>

<item>Cheque</item>

</string-array>

</resources>

You can then use the payment_types array list in code as follows:

string[] paymentTypes = Resources.GetStringArray(Resource.Array.payment_types);

Other folders you could add to your project structure as your application grows in complexity could include:

The Activity Class

It's worth spending a little time going through the Android Activity class in a little more detail as they are fundamental to building Xamarin.Android applications.

As already mentioned, an Activity defines a single, focused thing that the user can perform. Typically, an Activity will launch an Android layout (or screen). The user interacts with a layout (.AXML) file, but the functionality is defined within the Activity.

Essentially an Activity has four states.

- If an

Activity is in the foreground, then it is active or running. Only one Activity can be running at a time. Android holds all open Activities in a stack structure where they can be popped or pushed as necessary. - If an

Activity has lost focus but remains visible, then it is said to be paused. - An

Activity that has been paused can be killed in scenarios such as low memory where Android needs to free up resources. - If an

Activity is completely obscured by another Activity, then it is said to be stopped. - If an

Activity is paused or stopped, then the Android system can remove the Activity from memory. It can do this by requesting that the Activity finishes, or it can simply kill the Activity. When the Activity is displayed again to the user, it needs to be restarted and restored to its previous state.

The following diagram (extracted from Android Developers) shows the lifecycle of an Activity.

Here is the code from the default Activity Activity1.cs.

using System;

using Android.App;

using Android.Content;

using Android.Runtime;

using Android.Views;

using Android.Widget;

using Android.OS;

namespace MyDemo

{

[Activity(Label = "MyDemo", MainLauncher = true, Icon = "@drawable/icon")]

public class Activity1 : Activity

{

int count = 1;

protected override void OnCreate(Bundle bundle)

{

base.OnCreate(bundle);

SetContentView(Resource.Layout.Main);

Button button = FindViewById<Button>(Resource.Id.MyButton);

button.Click += delegate { button.Text = string.Format("{0} clicks!", count++); };

}

}

}

Note how the Activity sets the layout (or screen) to use. It does this by invoking the function SetContentView(). Note how the layout name is passed as an argument to the function rather than its ID. The resource definition for the Main layout is contained in the file Resource.Designer.cs that was mentioned earlier. This file maps the name of the layout (which in this case is called Main) to its ID. The ID will be a unique integer value.

Note how the generated ID for the Button UI element is determined using the Android function FindViewById(). All Android UI elements have an associated ID. This ID is defined in the file Resource.Designer.cs.

Resources

We have briefly mentioned the file Resource.Designer.cs and how it maps the name of a resource to its generated ID.

When you create layouts in Android, you will add Views (a View is an Android term to refer to any UI element such as buttons, textboxes, checkboxes, etc.). You will give these UI elements a meaningful name (btnAddNewCustomer, txtCustomerSurname for example). When you need to refer to these UI elements in your application code, you determine its name via its generated ID.

The following code snippet shows the class definitions for the Id and Layout classes. Each ID is defined as a const int. This shows clearly how a UI element (layout, button, etc.) is mapped to its generated ID. Whenever you add / delete UI elements to your layouts or add / delete layouts themselves, the Resource.Designer.cs file is automatically updated when you compile the application. So there is no need to manually edit this file!

namespace MyDemo

{

public partial class Resource

{

public partial class Id

{

public const int MyButton = 2131034112;

private Id()

{

}

}

public partial class Layout

{

public const int Main = 2130903040;

private Layout()

{

}

}

}

}

The Fragment Class

The Fragment class is another important Android element to understand when building a Xamarin.Android application. They represent a portion of the user interface in an Activity. You can think of a Fragment as a modular section of an Activity. They have their own lifecycle and events similar to an Activity. An Activity may be associated with zero or more Fragments.

In common with an Activity a Fragment can receive its own input events. You can add / remove a Fragment from an Activity or even from another Fragment at runtime. A Fragment can be added dynamically to different Activities and Fragments and therefore enable reusability.

The following diagram (extracted from Android Developers) shows the lifecycle of a Fragment.

In the following code snippet, clicking on the Notepad button invokes the Notepad Fragment (which is a screen for allowing users to enter notes into the application).

public class MyActivity : Activity

{

protected override void OnCreate(Bundle bundle)

{

var notePadButton = FindViewById<Button>(Resource.Id.btnNotepad);

notePadButton.Click += (o, e) =>

{

var ft1 = FragmentManager.BeginTransaction();

var current = FragmentManager.FindFragmentById(Resource.Id.layoutFrame);

ft1.Remove(current);

ft1.Add(Frame, new Notepad());

ft1.Commit();

};

}

}

The same code could be used to launch the Notepad Fragment from any other part of the application, whether it was from an Activity or from another Fragment. Fragments enable reusability of functionality.

The Intent Class

An Intent is a messaging object that can be used to represent an action from another component. There are three fundamental uses for an Intent.

- To start an

Activity - To start a

Service - To start a

Broadcast

In the following example, the Admin page Activity contains a button for launching the user group Activity screen which is responsible for assigning a user to a user group. This is achieved by using an Intent.

public class AdminPage : Activity

{

protected override void OnCreate(Bundle bundle)

{

base.OnCreate(bundle);

SetContentView(Resource.Layout.AdminScreen);

var assignUserButton = FindViewById<Button>(Resource.Id.btnAssignUser);

assignUserButton.Click += (o, e) =>

{

var intent = new Intent(this, typeof(UserGroupActivity));

StartActivity(intent);

Finish();

};

}

}

The Application Class

If you need to maintain state across your application, then you will need an Application class. Although it is possible to pass information to / from Activity and Fragment classes, if you have a requirement to maintain global state (such as the currently logged in user name), then you achieve this using an Application class.

[Application]

public class MyApplication : Application

{

public string CurrentUser = "";

}

Note that the class is decorated with the [Application] attribute. This is so that the necessary element is generated and added to the AndroidManifest.xml file. This ensures the class is instantiated when the application / package is created.

="1.0"="utf-8"

<manifest xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android"

android:installLocation="auto" package="com.mydemo.apk" android:versionCode="1">

<application android:label="MyDemo" android:icon="@drawable/Icon"></application>

</manifest>

To use the Application class in your own code, you will also need to determine the current Context. In Android, the Context refers to the current state of the application / object. The Context class is also the base class for (but not limited to)

Activity classService class

There are several ways in which you can determine the application Context. One way is to add a method to your Application class definition that returns the Context as in the following code:

[Application]

public class MyApplication : Application

{

public Context GetContext()

{

return ((this).ApplicationContext);

}

}

Then in your application code, you can invoke it as follows.

MyApplication application = (MyApplication)GetContext();

String username = application.GetCurrentUser();

String password = application.GetPassword();

The Android Manifest

Your Xamarin.Android application will fail to run without this file. It defines important information about your application to the Android system and it MUST be called AndroidManifest.xml. No other name can be used. It is broadly similar to a web application's web.config file.

The manifest file defines essential information including (but not limited to):

- The name of the application

- Describes the components of the application

- Declares permissions

- Defines the minimum Android API level

The diagram below shows the basic structure of the manifest file and the various elements it can contain.

<manifest>

<uses-permission />

<permission />

<permission-tree />

<permission-group />

<instrumentation />

<uses-sdk />

<uses-configuration />

<uses-feature />

<supports-screens />

<compatible-screens />

<supports-gl-texture />

<application>

<activity>

<intent-filter>

<action />

<category />

<data />

</intent-filter>

<meta-data />

</activity>

<activity-alias>

<intent-filter> . . . </intent-filter>

<meta-data />

</activity-alias>

<service>

<intent-filter> . . . </intent-filter>

<meta-data/>

</service>

<receiver>

<intent-filter> . . . </intent-filter>

<meta-data />

</receiver>

<provider>

<grant-uri-permission />

<meta-data />

<path-permission />

</provider>

<uses-library />

</application>

</manifest>

Below is an example of an AndroidManifest.xml file.

="1.0"="utf-8"

<manifest xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android"

android:installLocation="internalOnly" android:icon="@drawable/mydemo"

package="com.mydemo.app" android:versionCode="13" android:versionName="0">

<uses-sdk android:targetSdkVersion="15" android:minSdkVersion="15" />

<application android:label="MyDemo"

android:theme="@android:style/Theme.Holo.NoActionBar.Fullscreen"

android:icon="@drawable/mydemo"></application>

<service android:enabled="true" android:name=".BackgroundService" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.ACCESS_COARSE_LOCATION" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.ACCESS_FINE_LOCATION" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.ACCESS_LOCATION_EXTRA_COMMANDS" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.ACCESS_NETWORK_STATE" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.ACCESS_WIFI_STATE" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.BATTERY_STATS" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.BLUETOOTH" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.BLUETOOTH_ADMIN" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.CAMERA" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.CHANGE_NETWORK_STATE" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.CHANGE_WIFI_MULTICAST_STATE" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.CHANGE_WIFI_STATE" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.CONTROL_LOCATION_UPDATES" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.DEVICE_POWER" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.FLASHLIGHT" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.FORCE_BACK" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.GET_PACKAGE_SIZE" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.GET_TASKS" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.INSTALL_LOCATION_PROVIDER" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.INSTALL_PACKAGES" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.INTERNET" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.KILL_BACKGROUND_PROCESSES" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.MODIFY_AUDIO_SETTINGS" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.MODIFY_PHONE_STATE" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.READ_CALENDAR" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.READ_CONTACTS" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.READ_INPUT_STATE" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.READ_LOGS" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.READ_OWNER_DATA" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.READ_PHONE_STATE" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.SET_ALARM" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.RECORD_AUDIO" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.SET_ORIENTATION" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.SET_TIME" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.SET_TIME_ZONE" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.STATUS_BAR" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.UPDATE_DEVICE_STATS" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.VIBRATE" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.WAKE_LOCK" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.WRITE_APN_SETTINGS" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.WRITE_CALENDAR" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.WRITE_CONTACTS" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.WRITE_EXTERNAL_STORAGE" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.WRITE_OWNER_DATA" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.WRITE_SECURE_SETTINGS" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.WRITE_SETTINGS" />

</manifest>

Designing and Architecting Your Application

The topic of designing and architecting a Xamarin.Android application is worthy of an article of its own, so I won't go into vast amounts of detail. Since it is more difficult to retro-fit design elements into your application afterwards, it is worth getting these firmly in place from the outset.

There are no hard and fast rules as to how you design and architect your Xamarin.Android application, but there are guidelines that you may want to consider.

Firstly, I would create subclasses of the key Android classes, i.e., ActivityBase, FragmentBase, AdapterBase and so on. Then populate these classes with the generic behaviour that is required. When creating a new Android class, ensure it inherits from your own derived version of the class. This enables reusability and leads to easier maintenance as you can change base behaviour in one place.

It is worthwhile ensuring your application is loosely coupled and that there are clear separation of concerns between the various parts of the application. An n-tier architecture is therefore worth exploring.

- User-interface layer

- Business rules layer

- Data layer

In the following example, the login button invokes a method of the Activity which in turn calls a business rule to determine if the user's credentials are correct. It doesn't matter if the function invokes a web service or a data layer function (which in turn looks up the user in the local database). The important point is that there is a clear separation of concerns between the various parts of the application. The actual details of how the application is architected is for the developer to decide.

public class LoginPage : Activity

{

protected override void OnCreate(Bundle bundle)

{

base.OnCreate(bundle);

var userNameText = FindViewById<EditText>(Resource.Id.txtUserName);

var passwordText = FindViewById<EditText>(Resource.Id.txtPassword);

var loginButton = FindViewById<Button>(Resource.Id.btnLogin);

loginButton.Click += (o, e) => PressLoginButton(userNameText.Text, passwordText.Text);

}

private void PressLoginButton(string username, string password)

{

return BizRules.IsUserAuthenticated(username, password);

}

There doesn't seem to be any agreement as to whether an Android application is a good fit for the MVC design pattern. The arguments against its use include the fact that the Activity serves as both the View and the Controller and that an Activity has its own events and lifecycle that don't fit with MVC. I'm not going to go into this in any detail except to make you aware of the lack of any general agreement on the subject, and that if you wish to implement MVC, then you are free to investigate the matter further.

Unit-testing Your Application

If you are considering unit-testing your application, then you will need to architect your application in a way that supports this. You will need to make these changes from the very outset as attempting to retro-fit them afterwards will entail significant effort. Also, if you are considering targeting other mobile platforms in the future (iOS, Windows Phone), then architecting them with unit-testing in mind will ensure that this is achievable.

NUnit does not work with Xamarin.Android nor do any other unit-testing frameworks. The intent of Monodroid and Monotouch is to provide a .NET development environment that allows you to easily port business logic between different environments. As a result, you can't really test Android / iOS specific code, but you can test generic .NET business logic code. In the Monodroid projects that I write, I create three projects in the solution. One is the Android project, another is a .NET project that holds all of my non-Android business logic and the final project is an NUnit test project which tests the functionality in the aforementioned .NET business logic project. Monodroid project files cannot be tested, but .NET code files linked into Monodroid projects can be tested with whatever unit-testing framework you choose.

Your solution should therefore contain the following three projects:

- A project which contains the

Xamarin.Android specific functionality and which has been created from a Xamarin.Android project template - A project which contains your business logic (you can add another project for your data layer if necessary)

- A project containing your unit tests

The key therefore to unit-testing your Xamarin.Android application is to keep all your Xamarin.Android code in a separate project. So out of the three projects in the solution described above, only one would be a Xamarin.Android project. It is by creating your solution in this way that you will be able to target other mobile platforms as you can reuse your business logic and test projects.

Summary

Hopefully, this article has given you sufficient information for you to start creating your own Xamarin.Android applications. Feel free to leave a comment if you would like me to further elaborate on anything within this article.