Note: This is the second in a series of articles covering joins.

The series starts with the article Introduction to Database Joins. All the examples for this lesson are based on Microsoft SQL Server Management Studio and the AdventureWorks2012 database. In this article, we are going to cover inner joins.

An inner join is used when you need to match rows from two tables. Rows that match remain in the result, those that don’t are rejected. The match condition is commonly called the join condition. When the match conditions involve equality, that is matching exactly the contents of one column to another, the join is called an equijoin. You’ll find that most of the joins you’ll use are equijoins. A common situation is where you need to join the primary key of one table to the foreign key of another. This is needed when you are denormalizing data.

Basic Structure of INNER JOIN

Below is an example of simple select statement with an INNER JOIN clause.

SELECT columnlist

FROM maintable

INNER JOIN secondtable ON join condition

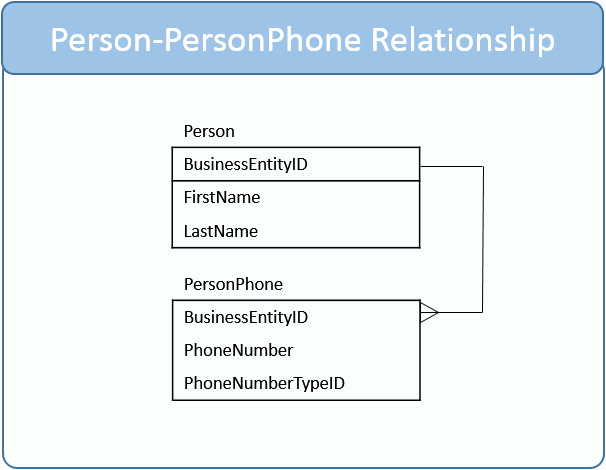

Consider if you want to create a directory of people and their phone numbers. To do so, you need to combine rows from the Person and PersonPhone tables.

The SQL to do this is:

SELECT Person.FirstName,

Person.LastName,

PersonPhone.PhoneNumber

FROM Person.Person

INNER JOIN

Person.PersonPhone

ON Person.BusinessEntityID =

PersonPhone.BusinessEntityID

This type of join is called an equi-join, since we are using an equality for the join condition. It's pretty safe to say that the vast majority of the joins you encounter are equi-joins. There are special circumstances where it makes sense to use other comparisons such as not equals or greater than. Those type of joins, called non equi-joins, are explored later in this post. Once the data is joined, it can also be filtered and sorted using familiar WHERE and ORDER BY clauses. The order of the clauses is what you might expect:

SELECT columnlist

FROM maintable

INNER JOIN secondtable ON join condition

WHERE filter condition

ORDER BY columnlist

The WHERE clause can refer to any of the fields from the joined tables. To be clear, it is best practice to prefix the columns with the table name. The same goes for sorting. Any field can be used; however, it is common to sort by one or more fields you are selecting. Let’s take our phone directory, but only list people, in order of last name, those whose last names start with C. With this requirement in mind, our SQL statement becomes:

SELECT Person.FirstName,

Person.LastName,

PersonPhone.PhoneNumber

FROM Person.Person

INNER JOIN

Person.PersonPhone

ON Person.BusinessEntityID =

PersonPhone.BusinessEntityID

WHERE Person.LastName LIKE 'C%'

ORDER BY Person.LastName

Notice the join condition remains the same. The only changes are the addition of the WHERE and ORDER BY clauses. By now, these should be familiar to you.

Table Aliases

As you create more complicated SQL statements, they can become difficult to read. Much of this is due to the verbose (wordy) nature of the language. You can cut down on some of this by using another name for your tables in statements. This is done using table aliases. Think of aliases like nicknames. They are easily defined. Just place them after the first reference of the table name. Here is a simple example where we alias the Person table as P:

SELECT P.FirstName,

P.LastName

FROM Person.Person AS P

In this example, we used the letter P. It could really be any number of characters, but I like to keep aliases simple. Where aliases really come in handy is with joins. Let’s take the last join we did, but this time write it by aliasing Person as P and PersonPhone as PP. Here is the statement:

SELECT P.FirstName,

P.LastName,

PP.PhoneNumber

FROM Person.Person AS P

INNER JOIN

Person.PersonPhone AS PP

ON P.BusinessEntityID = PP.BusinessEntityID

WHERE P.LastName LIKE 'C%'

ORDER BY P.LastName

Regarding naming, I suppose you could alias your tables, A,B,C, but it can become hard to remember the aliases. My system to keep the aliases short, yet easy to remember, is it uses the first letter of the table. If the table has two words, like PersonPhone, I’ll typically use the first letter of each word.

Join with More than One Field

In some cases, you may find that you need to join two or more fields together. This happens when a table’s primary key consists of two or more columns. This is easily done using an AND operator and an additional join condition.

Consider an example where we want to know all the days and times each instructor teaches a class. In our example, the primary key for the Class table is two fields: ClassName and Instructor. To construct the schedule, we need to join Class to Section by matching both ClassName and Instructor.

SELECT C.Instructor,

C.ClassName,

S.Day,

S.Hour

FROM Class AS C

INNER JOIN

Section AS S

ON C.ClassName = S.ClassName

AND C.Instructor = S.Instructor

ORDER BY C.Instructor, S.Day, S.Hour

Note: This example won’t work in the AdventureWorks2012 database.

When creating joins, it is important to pay attention to your data. In our example, if we mistakenly joined Class with the Section table using only the ClassName column, then each instruction’s class listing would also include schedules from other instructions that teach the same class. A join will match as many rows as it can between tables. As long as the join condition is satisfied, combinations of rows are included. Because of this, it is important to understand each table’s primary key definition and to know how tables’ are meant to relate to one another.

Joining Three or More Tables

In the AdventureWorks2012 database, you need to join to the PhoneNumberType table to know whether a listed phone number is a home, cell, or office number. In order to create a directory of names, phone number types, and numbers three tables must be joined together. This relationship is shown below:

Including another table in our query is as simple as adding another INNER JOIN clause to our statement.

SELECT P.FirstName, P.LastName,

PP.PhoneNumber

FROM Person.Person AS P

INNER JOIN

Person.PersonPhone AS PP

ON P.BusinessEntityID = PP.BusinessEntityID

INNER JOIN

Person.PhoneNumberType AS PT

ON PP.PhoneNumberTypeID = PT.PhoneNumberTypeID

WHERE P.LastName LIKE 'C%'

ORDER BY P.LastName

I don’t think there is any hard and fast rule to how you format the join clause, I tend to separate them on their own lines and when specifying the columns, place the “join from” column first, as:

INNER JOIN

ToTable

On FromTable.PKID = ToTable.FKID

For all the examples in this article, I first wrote the statement and then used TidySQL to automatically format them.

Self-Join

A self-join is when you join a table to itself. When you use a self-join, it is important to alias the table. Suppose we wanted to list all departments within a department group. In the AdventureWorks2012 database, this is done using the following self-join:

SELECT D1.Name,

D2.Name

FROM HumanResources.Department AS D1

INNER JOIN

HumanResources.Department AS D2

ON d1.GroupName = d2.GroupName

Since the Department table is being joined to itself, we need distinguish the two occurrences of Department. They are aliased as D1 and D2. Other than the tables being the same, you see there is nothing remarkable about this type of join.

Non Equi-Joins

A non equi-join is just a fancy way of saying your join condition doesn’t have an equals sign in it. You may be scratching your head wondering why you would want to use a non equi-join. I agree, to be honest, it can be hard to think up examples; however, they do exist, and you’ll appreciate knowing how to use them when you need to do so. One reason to use a non equi-join is when you need to verify that you have clean data. Consider the AdventureWorks2012 Products table. You may want to check that the product name is unique for each product listed. One way to do this is to self-join the product table on Name.

SELECT P1.ProductID,

P1.Name

FROM Production.Product AS P1

INNER JOIN

Production.Product AS P2

ON P1.Name = P2.Name

ORDER BY P1.ProductNumber

This query allows us to compare values for each row that matches the Product Name. If Name is unique, then the only matches you should have are when the ProductIDs are equal. So, if we are looking for duplicate Product Name, it follows that we want to find records that match having different ProductIDs. This is shown in the diagram below:

The SQL to return the duplicate records is:

SELECT P1.ProductID,

P1.Name,

P1.ProductNumber

FROM Production.Product AS P1

INNER JOIN

Production.Product AS P2

ON P1.Name = P2.Name

AND P1.ProductID <> P2.ProductID

ORDER BY P1.ProductNumber

You may wonder what happens first. Does the computer first match the names and then, once that is complete look for ProductIDs that don’t match, or does it somehow evaluate both conditions as it builds the result? The beauty of SQL is that, in theory, the way you write your code shouldn’t have an influence on how the database actually retrieves the data. The order of the joins or conditions shouldn’t significantly influence the time a query runs. This will all be explored when we talk about the query optimize and how to review query plans.