Semantic Database

Concept

Architecture

Implementation

Introduction

This article discusses the concept of a semantic database in several sections:

- Discussion of the concept and need for a semantic database

- Architectural Implications

- Implementation on top of an RDBMS

- Unit tests to vet basic insert and query operations (we'll leave update and delete for later)

Part II will demonstrate the semantic database in action in the Higher Order Programming Environment with a useful application. If you are unfamiliar with HOPE, this page will refer you to the other articles here on Code Project. Because I'm writing the semantic database as a persistence component, you'll notice that the unit tests are interacting with "carriers", which is the vehicle for sending messages between "receptors" -- the stand-alone components. Also, because I'm talking about a semantic database, I'm leveraging the classes in HOPE that manage semantic structures, including the dynamic runtime compilation and instantiation of semantic structure instances. So there's a lot of prior work being used here as the scaffolding, but I doubt this will get in the way of understanding the concepts and the code.

As many of my readers will be used to by now, this is definitely going to be a walk on the wild side. The concepts, architecture, and implementation will hopefully challenge your preconceptions of what data is, and by corollary, what a semantic database is.

The reader will hopefully also forgive the rather deep foray into a non-technical discussion regarding semantics, as it is important to convey the necessary foundational information.

Lastly, even if you're not specifically interested in semantic database architectures, the code for generating the SQL query statements is useful in any application where you want to automate the joining of multiple tables based on schema information rather than hand-coding the complex joins or relying on an ORM.

Where's the Code?

As usual, the code can be cloned or forked from GitHub. In Part II, I'll have a branch specific to the code that goes along with that article.

What is a Semantics?

Semantics is an emerging field of research and development in information science, however, the concept has been around for a lot longer than computers! To begin with, semantics is the branch of linguistics and logic concerned with meaning. This can be broken down into three major categories:

- Formal Semantics

- Logical aspects of meaning:

- Sense

- Reference

- Implication

- Logical form

- Lexical Semantics

- Word meaning

- Word relations

- Conceptual Semantics

- Cognitive structure of meaning

Or, to put it a bit more concretely:

- Semantics is the study of meaning

- It focuses on the relationship between:

“No word has a value that can be identified independently of what else is in its vicinity.”

-- (de Saussure, Ferdinand, 1916, The Course of General Linguistics)

What is the Typical Concept of a Semantic Database?

First off, the term "semantic database" is classically used in conjunction with the phrase "semantic data model1". And when you see the phrase "semantic data", this usually implies some association with the Semantic Web2, the Web Ontology Language (OWL)3, and the Resource Description Format (RDF)4.

The Semantic Web

"The semantic web is a vision of information that can be readily interpreted by machines, so machines can perform more of the tedious work involved in finding, combining, and acting upon information on the web. The Semantic Web, as originally envisioned, is a system that enables machines to "understand" and respond to complex human requests based on their meaning. Such an "understanding" requires that the relevant information sources be semantically structured."2

OWL and RDF

Unfortunately, the original concept and phrase, coined by Tim Berners-Lee (also the inventor of the World Wide Web) has been somewhat hijacked by OWL and RDF. OWL and RDF primarily focus on what is known as "triples" -- subject-predicate-object expressions, where "[t]he subject denotes the resource, and the predicate denotes traits or aspects of the resource and expresses a relationship between the subject and the object."4 The roots of this can be traced to the 1960's, when "Richard Montague proposed a system for defining semantic entries in the lexicon in terms of the lambda calculus. In these terms, the syntactic parse of the sentence John ate every bagel would consist of a subject (John) and a predicate (ate every bagel); Montague demonstrated that the meaning of the sentence altogether could be decomposed into the meanings of its parts and in relatively few rules of combination."8

However, this correlates very poorly with the pure concept of semantics, especially with regards to relationships and structure. While a subject-predicate-object expression defines the relationship between the subject and object, it in no way defines the relationship between subjects, and between objects. Furthermore, an S-P-O also fails to express the composition, or structure of an object or subject, which, from a semantic perspective, is critical.

Obviously one can, with little thought, create a database of subject-predicate-object triples. One can then even query the database for kinds of relationships (via their predicates) that subject have to all objects in the domain (or objects and their subjects.) The problem is, this approach leaves one open to the challenges of the semantic web: "vastness, vagueness, uncertainty, inconsistency, and deceit."2 Why? Because triples do not actually convey much meaning in a machine usable sense and are therefore prone to the aforementioned issues. Ironically, while a triple includes the relationship between subject and object, it does not say anything about the structure of the subject or the object (or even the predicate, which could have its own structure as well.) Take, for example, the issue of underspecification:

"...meanings are not complete without some elements of context. To take an example of one word, red, its meaning in a phrase such as red book is similar to many other usages, and can be viewed as compositional.[6] However, the colours implied in phrases such as red wine (very dark), and red hair (coppery), or red soil, or red skin are very different. Indeed, these colours by themselves would not be called red by native speakers. These instances are contrastive, so red wine is so called only in comparison with the other kind of wine (which also is not white for the same reasons)."6

If the full structure is persisted along with the data ("red"):

and that structure is retrieved when querying for, say "things that are red", then its meaning is not ambiguous.

We note that the parent elements are valueless -- they are only placeholders referencing the child element "Color."

We note that the parent elements are valueless -- they are only placeholders referencing the child element "Color."

What is the "Correct" Concept of a Semantic Database?

Like Alice in Wonderland, we have to go down a few rabbit holes to figure this out.

"Many sites are generated from structured data, which is often stored in databases. When this data is formatted into HTML, it becomes very difficult to recover the original structured data. Many applications, especially search engines, can benefit greatly from direct access to this structured data."5

In other words, by exposing the semantics of the data, machines can then utilize the information in more interesting ways than just storing it or displaying it. A classic example is a website that contains a phone number. If the phone number is has a semantic tag, then your smart phone can easily offer it up as number to dial. Contrast this with the hoops an application has to go through to scan a page and find text that matches any number of styles of presenting a phone number, validating that it is actually a number rather than a math expression that looks like "619-555-1212", etc.

Structured Data

In the above quote, you'll notice the phrase "recover the original structured data." This implies that the data has structure -- it's not just a field, but the fields mean something and can have sub-structures -- in other words, the structured data is a tree.

Here's a couple examples:

Next, we need to understand the concept of "ontology", a term that is often involved in discussions regarding semantics.

Ontology

"An ontology is an explicit specification of a conceptualization."

-- Gruber, Tom (1993); "A Translation Approach to Portable Ontology Specifications", in Knowledge Acquisition, 5: 199-199

Earlier I pointed out that the S-P-O triple does not define the relationship between subjects, and between objects. This is where ontology comes in. While in the abstract, "ontology" means "the branch of metaphysics dealing with the nature of being," in information science, "an ontology is defined as a formal, explicit specification of a shared conceptualization. It provides a common vocabulary to denote the types, properties and interrelationships of concepts in a domain."9 And notice: "Ontologies are the structural frameworks for organizing information and are used in ...the Semantic Web..."

Semantics are useful for understanding the structure of a "thing", however we need ontologies to relate things with other things. Therefore, one would expect that a semantic database be relational -- it should be able to relate structured data into ontologies.

Here is an example instance of the Friend of a Friend10 ontology (from the W3C SKOS Core Guide11):

The SKOS Core Vocabulary defines two properties of a semantic relationship:

- The relationship between the two structures defines one as being "broader" or "narrower" with relation to the other

- An associative relationship, in which the two structures are "related"

In the world of the semantic web, and RDF Schema (RDFS)12 is used to describe ontologies "...otherwise called RDF vocabularies, intended to structure RDF resources. These resources can be saved in a triplestore to reach them with the query language SPARQL."12 For example: "A typical example of an rdfs:Class is foaf:Person in the Friend of a Friend (FOAF) vocabulary. An instance of foaf:Person is a resource that is linked to the class foaf:Person using the rdf:type property, such as in the following formal expression of the natural language sentence : 'John is a Person'."12

We see two concepts emerging:

- The relationship between data structures is itself a hierarchical structure

- A semantic structure can be associated with another structure to create ontologies

This guides us in understanding what a semantic database should provide.

A Semantic Database

In a semantic database (going back to the very early definition of semantics), the schema:

- describes denotations

- describes relationships between denotations

The job of the database then is to associate signifiers (values) to those denotations. Therefore:

- Structure resolves to concrete properties to which instance values can be associated

Importantly though, the structure is instantiated with each instance. This allows the structure to be retrieved along with the value(s). We will see what this means (and why what I'm implementing is going to seem so controversial) later.

Why not use a Relational Database?

In the implementation section of this article, I'll be working a lot with RSS feeds, so let's take a look at a typical implementation in an RDBMS for persisting an RSS Feed and its entries. First off, the schema probably looks something like this:

- RSS_Feed_Name

- RSS_Feed_Item

- FK_RSS_Feed_Name

- Title : text

- Description: text

- PubDate : date

- Url : text

- RSS_UI

- FK_RSS_Feed_Item

- Visited : bool

- Displayed : bool

|

|

(Here the RSS_UI is intended to persist whether a feed item has been displayed previously in a list or whether it is a new feed, and whether the user actually visited the URL associated with the feed item.)

Notice how the field names are high level abstractions. Given the field name, one has no idea whether the "Title" refers to an RSS feed, a book, or a the title given to a person. Adding "RSS_Feed_" to the field names is cumbersome and non-traditional. Furthermore, when we perform the query "select * from RSS_Feed_Item", we get a collection of rows in the order that the fields were described in the schema. However, these are just values -- we all too often forget that the data returned has actually no semantic meaning, it is the UI that labels the columns for us so we know what the data is.

Even more importantly, in an RDBMS, relationships are driven by:

- Cardinality

- Normalization rules

- "Logical" groupings of fields

This process can be so automatic when we create a schema that we are hardly consciously aware that we are doing it. The result are associations that are not semantic but rather abstracted, un-natural structural relationships, (ideally) restricted to established foreign key declarations.

However, as we will see, we can implement a semantic database on top of an RDBMS.

Why not use a NoSQL Database?

NoSQL databases are document-oriented and they do not support relationships between documents such that one can construct a query that consists of joins that is handled by the database engine. Instead, in a NoSQL database, joins are resolved by the client, which requires potentially numerous round trips to the database to acquire all the information and then build it into a coherent structure. This makes NoSQL database completely unsuitable for the task at hand.

Why not use a Graph Database?

Graph databases do seem to be a possibility and will be investigated further. If we read about Neo4j:

From Neo4j's website:

"...a graph is just a collection of vertices and edges—or, in less intimidating language,a set of nodes and the relationships that connect them. Graphs represent entities as nodes and the ways in which those entities relate to the world as relationships." - Robinson, Ian, & Webber, Jim, & Eifrem, Emil (2013). Graph Databases. O'Reilly, pg 1 (free download here.)

Importantly, with regards to traditional relational databases:

"...relational databases were initially designed to codify paper forms and tabular structures—something they do exceedingly well—they struggle when attempting to model the ad hoc, exceptional relationships that crop up in the real world. Ironically, relational databases deal poorly with relationships. Relationships do exist in the vernacular of relational databases, but only as a means of joining tables. In our discussion of connected data in the previous chapter, we mentioned we often need to disambiguate the semantics of the relationships that connect entities, as well as qualify their weight or strength. Relational relations do nothing of the sort." - (ibid, pg 11)

And:

"Relationships are first-class citizens of the graph data model, unlike other database management systems, which require us to infer connections between entities using contrived properties such as foreign keys, or out-of-band processing like map-reduce. By assembling the simple abstractions of nodes and relationships into connected structures, graph databases enable us to build arbitrarily sophisticated models that map closely to our problem domain. The resulting models are simpler and at the same time more expressive than those produced using traditional relational databases and the other NOSQL stores." - (ibid, pg 6)

However, it would appear that a typical graph database focuses on the ontology of information -- it has no concept of the actual structures that define the properties of a node. This is a result of the concept of "facts": "When two or more domain entities interact for a period of time, a fact emerges. We represent these facts as separate nodes, with connections to each of the entities engaged in that fact." - (ibid, pg 66)

We can see this in the examples given for creating a graph database. From pg 41:

We have "fact" nodes:

- William Shakespeare

- The Tempest

- Juilias Ceasar

This information lacks semantic context, for example indicating that "William Shakespeare" is a playwright or that "The Tempest" is a play. Interestingly, this semantic information becomes an arbitrary label in the Cypher14 query fragment bard=node:author(lastname='Shakespeare'). From the query we can determine that William Shakespeare is a bard, however, this information is completely lost in the graph database!

To put it another way, if we follow the "fact" best practice, it becomes impossible to query a graph database for data by specifying a semantic context. I cannot ask the graph database "show me all the people that are bards" unless I explicitly create a node called "bard" with a relationship to William Shakespeare. This problem stems partially from the fact that a graph database represents a specific domain: "By assembling the simple abstractions of nodes and relationships into connected structures, graph databases enable us to build arbitrarily sophisticated models that map closely to our problem domain." - (ibid, pg 6). At best, we can say a node with properties "firstname" and "lastname" represents a "person", but we can say nothing else about that person, such as distinguishing the person from the playwright, the producer, or the actor, except through a relationship with another concrete node, where the relationship provides further semantic meaning, such as "wrote_play", or "produced_play" or "acted_in".

Therefore, with regards to semantic structure, a graph database, while an excellent tool for creating ontologies of concrete entities, is not appropriate for abstract structural elements that have semantic significance but no values (which would have to be represented as nodes without properties), nor does a graph database properly semanticize property values, except as "field names" which, like traditional databases, the semantics are not accessible as part of the data.

Nonetheless, there is much guidance in the literature on graph databases that is valuable when designing a semantic database, and that is:

There is relevant meaning in the connections between semantic structures comprising the ontology.

A Semantic Database Architecture

In the above discussion, we come to several important observations:

- An ontology emphases the relationship of entities rather than defining the entity structure.

- Semantics emphasizes the structure but not the relationships between structures (the ontology.)

Furthermore, with regards to current database options:

- Graph databases typically capture ontologies of facts rather than semantics and their structures

- Relational databases capture "logical" relationships rather than "natural" semantic structures and ontologies

- NoSQL databases require that the client provides the implementation for supporting relationships, the only support NoSQL provides is a very limited "document ID" scaffolding.

What is needed is with regards to a semantic database is:

- The ability to create ontologies from semantics

- The ability to define the natural structure of the semantic elements

Using our RSS_Feed_Item example, we can put together a mockup of what the natural structure of the concept "RSS_Feed_Item" looks like:

- RSS_Feed_Item

- RSS_Feed_Name

- RSS_Feed_Title

- RSS_Feed_Description

- RSS_Feed_PubDate

- RSS_Feed_Url

(It certainly can also be argued that "URL" should be broken down into scheme name, domain name and resource path, but we'll keep it simple for now.)

The first thing to note with this structure is that queries can queries can be made at any level in the structure with varying degrees of meaning loss. For example, the query “select URL from RSS_Feed_Url” has some contextual loss, as we still know that the values are associated with a URL structure, but URL is no longer identified as being an RSS Feed URL. A query like “select Value from URL” has complete contextual loss -- all we get back are a collection of strings. Incidentally, this is the equivalent of querying an RDBMS “select URL from RSS_Feed_Item”. In the semantic database implementation that I propose here, the query "select Value from URL" would actually not be possible because Value is a native type, not a semantic type.

Using an RDMS to host a Semantic Database

However, a semantic database can be built on top of an RDBMS. We can leverage useful features of an RDBMS:

-

foreign key constraints

-

server-side joins

-

unique key constraints

-

unique key indexing

When hosted by an RDBMS, we see the following artifacts:

-

Tables represent structure

-

Foreign keys describe sub-structures

-

Joins are used to join together structures

-

In a left join, all-null native types for a semantic type takes on the specific meaning that there is no structure instance

-

The primary key is almost exclusively relegated to the role of resolving joins through the foreign key

-

There is significant more emphasis on the unique key (single field or composite) for performing insert, update, and delete transactions on native types.

Contrary to an RDBMS, where relationships are driven by cardinality, normalization, and logical structuring of fields, in a semantic database, relationships are driven by the semantic structure itself. This, by its very nature, allows a semantic database to be more adaptive to new structures that encapsulate new meaning.

Unfolding a Semantic Database Structure

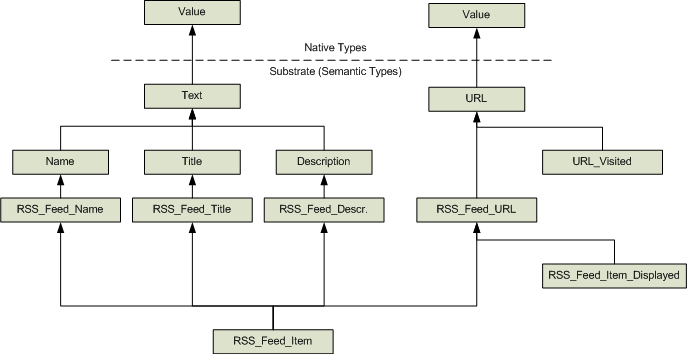

Using the RSS feed example, an unfolded structure of tables in a database would look something like this:

Notice that there are only two tables with actual values (Text and URL). Everything else is "substrate" - it's there only for its structural relevance and consists only of foreign keys pointing the next layer of generalized concept. While most structures have 1:1 relationships with their generalization, we see that RSS_Feed_Item is a composite of four distinct structures (this is its specific ontology.)

In object oriented terms, we can clearly see the "is a kind of" and "has a" relationships, however, it should be noted that a semantic database is in no way an implementation of an OODBMS, again for the same reason -- objects tend to be logical constructs for the convenience of the programmer rather than natural semantic constructs. However, a semantic structure quite naturally fits into the OO paradigm.

Folding a Semantic Database Structure

The typical structure however is illustrated more cleanly as a tree:

Implementation in an RDBMS

This is what the schema looks like in an RDBMS (and this is where I really start getting the "you're crazy" looks):

Two things stand out:

Two things stand out:

| The “deepest” semantic types are almost always composed just of foreign keys. |

| Tables with native types are very “thin”, having very few fields. |

What's interesting about this implementation is that we can now ask some potentially useful questions:

-

What are all the URL’s in the database?

-

What are the URL’s we have visited?

-

What URL’s are associated with feeds?

-

What are all the values of “Title”?

-

What are all the feed names?

These are not questions that we can necessarily ask of an RDBMS, especially when a more general concept like "URL" is embedded as a field across multiple tables: RSS Feed URL's, browser bookmark URL's, document embedded URL's, etc. Even a well-architected database will have its limitations.

Furthermore, because of how the more general semantic types are joined to contextual types, we can ask:

- Which feed items have I visited?

- Which feed items are bookmarked (I did not show the bookmark semantic types in the diagram)

Even more importantly (as an example), when we visit a page in a browser, we can use the same more generalized URL type with a specialized "browser visited" type, allowing us to ask specifically:

- What are all the feed items I've visited?

- What are all the web pages I've visited directly in my browser?

- What are all the URL's in total that I've visited?

Hopeful this demonstrates how a semantic database can adapt to new structures that then creates new contexts that can then be queried in new ways.

Some Benefits of a Semantic Database

- By preserving semantic structure, we can query the database at different levels of semantic meaning, from very specific to very general.

- For example, the semantic type “Title” is very general but allows us to ask “what are all the values of things having the meaning “Title”?

- By inspecting the relationships, we can ask “what are the things having “Title” in their meaning?

- When we query the database, we don’t just get back a list of records – we get back fully “rehydrated” semantic types.

- In actual implementation, the need for an ORM layer is eliminated:

- We pass in semantic structures as actual C# objects

- We get back semantic structures as actual C# objects

Some Drawbacks of a Semantic Database

- Tables and their fields are organized by hierarchical rather than logical structure:

- We usually think about organizing information into logical associations and relationships

- Hierarchical organization creates many more tables

- The number of joins in a query can degrade performance.

- Multiple insert operations are required to create the semantic type’s hierarchy.

- Designing hierarchies isn’t easy

- We need to learn how to think about multiple levels of abstraction.

- We need to think carefully about unique native types and unique semantic types.

- Writing SQL queries by hand is painful:

- lots of joins, often with multiple references to the native type tables making it hard to keep track of which FK join is associated with what meaning-value.

- Writing insert statements by hand is even more painful:

- multiple inserts from the bottom up, requiring the ID of the child table to populate the foreign key in the parent table.

Addressing Some of the Drawbacks

A Semantic Database engine can address some of these drawbacks:

- Automating SQL query generation

- Hides the hierarchy and table joins

- Automating SQL inserts

- Managing all the necessary FK ID’s

- Improving Performance

- Caching queries so the engine doesn’t have to re-create the SQL statement every time.

- Use prepared statements so the server isn’t parsing and analyzing the query statement every time it’s used.

Prototyping and Implementation

A semantic database naturally deals with semantic structures. As I've already implemented a great deal of the infrastructure in the Higher Order Programming Environment (HOPE) project (the up to date list of articles can be found by visiting here), I will be taking advantage of that code base.

It is highly recommended that the introductory articles are reviewed to help understand the following code. In the real demonstration that follows this section, I'll be taking advantage of the semantic editor and various "receptor" components, the semantic database being implemented as one such receptor.

Unit Tests

Unit tests are vital for verifying the expected behaviors when the user is expecting to trust our ability to properly persist and retrieve data (which is one of the reasons I'm also building this on top of an RDBMS rather than writing a completely new semantic database implementation.) Unit tests are also a good way of introducing the concepts and implementation of the semantic database.

You will notice the unit test structure as, basically:

- Clean up the database for every test - this involves dropping tables

- Create the semantic structures and their configurations that will test the desired behaviors

- Register these structures with the semantic database - this creates the backing tables

- Perform the desired transactions

- Verify the results.

An important consideration when working with any RDBMS, and this is true with regards to the semantic database as well, is the concept of unique keys, either single or composite fields. However, the semantic database also implements the concept of unique key "types", where the type is the semantic element. This creates some interesting behaviors for which need to test, and the tests will help to document how to use the unique key field / type configurations.

Database Configuration

If you run the tests with a SQLite database, there is no configuration required -- the database file is created automatically and there are no permission issues. The semantic database also supports Postgres, which requires that:

- a "postgres.config" file be placed in the "HOPE\UnitTests\SemanticDatabaseTests\bin\Debug" folder. This file should consist of two lines:

- The username

- The password

- You will also need to manually create an empty database (no tables) called "test_semantic_database"

Creating Tables From Semantic Structures

This code:

InitializeSDRTests(() => InitLatLonNonUnique());

sdr.Protocols = "LatLon";

sdr.ProtocolsUpdated();

initializes the semantic database receptor and defines a semantic structure for "LatLon". When ProtocolsUpdated is called, the semantic database creates the table "LatLon" with two fields, "latitude" and "longitude". Tables are automatically created when a new semantic type is encountered. In this particular case, the semantic structure is instantiated thus:

protected void InitLatLonNonUnique()

{

SemanticTypeStruct sts = Helpers.CreateSemanticType("LatLon", false, decls, structs);

Helpers.CreateNativeType(sts, "latitude", "double", false);

Helpers.CreateNativeType(sts, "longitude", "double", false);

}

For our purposes, we won't worry about what decls or structs are, you can inspect the code in detail if you want to find out. The salient point is that a structure "LatLon" is created with two native types, both doubles, called "latitude" and "longitude." Neither the structure nor the native types are defined as unique.

While it seems odd, the reason strings are used for type names -- rather than, say,

While it seems odd, the reason strings are used for type names -- rather than, say, typeof(double) -- is because we're actually simulating what would normally be done in the semantic editor, which, being a user interface component, works mostly with strings for the names of things.

The database implementation for creating the tables from a semantic structure is:

The database implementation for creating the tables from a semantic structure is:

protected void CreateTable(string st, List<string> fkSql)

{

List<Tuple<string, Type>> fieldTypes = new List<Tuple<string, Type>>();

ISemanticTypeStruct sts = rsys.SemanticTypeSystem.GetSemanticTypeStruct(st);

CreateFkSql(sts, fieldTypes, fkSql);

CreateNativeTypes(sts, fieldTypes);

dbio.CreateTable(this, st, fieldTypes);

}

protected void CreateFkSql(ISemanticTypeStruct sts, List<Tuple<string, Type>> fieldTypes, List<string> fkSql)

{

sts.SemanticElements.ForEach(child =>

{

string fkFieldName = "FK_" + child.Name + "ID";

fieldTypes.Add(new Tuple<string, Type>(fkFieldName, typeof(long)));

fkSql.Add(dbio.GetForeignKeySql(sts.DeclTypeName, fkFieldName, child.Name, "ID"));

});

}

protected void CreateNativeTypes(ISemanticTypeStruct sts, List<Tuple<string, Type>> fieldTypes)

{

sts.NativeTypes.ForEach(child =>

{

Type t = child.GetImplementingType(rsys.SemanticTypeSystem);

if (t != null)

{

fieldTypes.Add(new Tuple<string, Type>(child.Name, t));

}

else

{

fieldTypes.Add(new Tuple<string, Type>(child.Name, typeof(string)));

}

});

}

The object

The object dbio is an interface supporting the connection and syntax nuances for different physical databases such as SQLite, Postgres, SQL Server, etc.

Once created, we can inspect the database for, in this case, a very simple implementation. Here's what Postgres says about the table created by the above code:

CREATE TABLE latlon

(

id serial NOT NULL,

latitude double precision,

longitude double precision,

CONSTRAINT latlon_pkey PRIMARY KEY (id)

)

Each of our unit tests drops tables and recreates them to clear out the data from previous tests.

A Simple Non-Unique Key Insert Test

This test verifies that when we insert identical information, we get two records back:

This test verifies that when we insert identical information, we get two records back:

[TestMethod]

public void SimpleNonUniqueInsert()

{

InitializeSDRTests(() => InitLatLonNonUnique());

DropTable("Restaurant");

DropTable("LatLon");

sdr.Protocols = "LatLon";

sdr.ProtocolsUpdated();

ICarrier carrier = Helpers.CreateCarrier(rsys, "LatLon", signal =>

{

signal.latitude = 1.0;

signal.longitude = 2.0;

});

sdr.ProcessCarrier(carrier);

IDbConnection conn = sdr.Connection;

int count;

IDbCommand cmd = conn.CreateCommand();

cmd.CommandText = "SELECT count(*) from LatLon";

count = Convert.ToInt32(cmd.ExecuteScalar());

Assert.AreEqual(1, count, "Expected 1 LatLon record.");

sdr.ProcessCarrier(carrier);

cmd.CommandText = "SELECT count(*) from LatLon";

count = Convert.ToInt32(cmd.ExecuteScalar());

Assert.AreEqual(2, count, "Expected 2 LatLon records.");

sdr.Terminate();

}

In the above code, a "carrier" is created. Carriers are like little messenger pigeons that are used to communicate between receptors. Because the semantic database is implemented within a receptor, we have to pretend to send it a message. You can review the previous articles on HOPE to learn more about carriers, protocols, and signals, but the basic idea here is that we are creating a carrier for the protocol "LatLon" (whose semantic structure we defined earlier) and assigning values to the native type fields. The semantic engine generates the C# code for each semantic structure and instantiates it for us. Taking advantage of the

In the above code, a "carrier" is created. Carriers are like little messenger pigeons that are used to communicate between receptors. Because the semantic database is implemented within a receptor, we have to pretend to send it a message. You can review the previous articles on HOPE to learn more about carriers, protocols, and signals, but the basic idea here is that we are creating a carrier for the protocol "LatLon" (whose semantic structure we defined earlier) and assigning values to the native type fields. The semantic engine generates the C# code for each semantic structure and instantiates it for us. Taking advantage of the dynamic keyword, we can then assign values to the properties without requiring a C# interface declaration.

The reason we don't explicitly state "insert" somewhere in this carrier is because in the grand scheme of things, all we want to do is listen for particular semantic instances (protocol-signal), and if we see one, we persist it. The front-end UI allows us to choose which semantic types we persist, but the advantage is that any "receptor" emitting a particular protocol doesn't care about whether it's persisted or not -- basically, we've turned persistence into an optional component, decoupling it completely from any other computational units. This also means that we can implement different persistence mechanisms, traditional RDBMS, graph, even NoSQL, Excel export, etc.

The reason we don't explicitly state "insert" somewhere in this carrier is because in the grand scheme of things, all we want to do is listen for particular semantic instances (protocol-signal), and if we see one, we persist it. The front-end UI allows us to choose which semantic types we persist, but the advantage is that any "receptor" emitting a particular protocol doesn't care about whether it's persisted or not -- basically, we've turned persistence into an optional component, decoupling it completely from any other computational units. This also means that we can implement different persistence mechanisms, traditional RDBMS, graph, even NoSQL, Excel export, etc.

What's going on when we pass in a semantic structure? This triggers the insert/update algorithm, though we'll be focusing only on inserts in this article. The exposed "API" function sets up some initial state variables and calls a recursive method:

What's going on when we pass in a semantic structure? This triggers the insert/update algorithm, though we'll be focusing only on inserts in this article. The exposed "API" function sets up some initial state variables and calls a recursive method:

string st = carrier.Protocol.DeclTypeName;

ISemanticTypeStruct sts = rsys.SemanticTypeSystem.GetSemanticTypeStruct(st);

Dictionary<ISemanticTypeStruct, List<FKValue>> stfkMap = new Dictionary<ISemanticTypeStruct, List<FKValue>>();

ProcessSTS(stfkMap, sts, carrier.Signal);

Structures need to be inserted into the database from the bottom up to ensure foreign key integrity. The method ProcessSTS does this by drilling down to the lowest structural elements -- the ones that implement only native types. The top level function is straight forward, recursing into child semantic elements until the semantic element "bottoms out" into just native types:

protected int ProcessSTS(Dictionary<ISemanticTypeStruct, List<FKValue>> stfkMap, ISemanticTypeStruct sts, object signal, bool childAsUnique = false)

{

ProcessChildren(stfkMap, sts, signal, childAsUnique);

int id = ArbitrateUniqueness(stfkMap, sts, signal, childAsUnique);

return id;

}

When the algorithm bottoms out, the data is checked for unique semantic elements and native types, which determines whether to allow duplicates to be inserted and whether to perform an update or an insert.

As the algorithm works back up the semantic tree, the id's of the children are accumulated so that they can populate the parent's foreign key fields:

protected void ProcessChildren(Dictionary<ISemanticTypeStruct, List<FKValue>> stfkMap, ISemanticTypeStruct sts, object signal, bool childAsUnique)

{

sts.SemanticElements.ForEach(child =>

{

ISemanticTypeStruct childsts = child.Element.Struct;

object childSignal = GetChildSignal(signal, child);

if (childSignal != null)

{

int id = ProcessSTS(stfkMap, childsts, childSignal, (sts.Unique || childAsUnique));

RegisterForeignKeyID(stfkMap, sts, child, id);

}

});

}

Each child ID is associated with its name (auto-generated by the semantic database engine) and its parent semantic element, such that each semantic element has a list of 0 or more foreign key relations when all the children have been processed:

protected void RegisterForeignKeyID(Dictionary<ISemanticTypeStruct, List<FKValue>> stfkMap, ISemanticTypeStruct sts, ISemanticElement child, int id)

{

string fieldName = "FK_" + child.Name + "ID";

CreateKeyIfMissing(stfkMap, sts);

stfkMap[sts].Add(new FKValue(fieldName, id, child.UniqueField));

}

The unique native type, semantic element (the foreign key and all child, grandchild, etc elements and native types) and semantic structure (all child, grandchild, etc elements and native types) is arbitrated by checking various flags that are set for the specific semantic structure or by its parent. I realize that was a mouthful, so let's look at the code:

protected int ArbitrateUniqueness(Dictionary<ISemanticTypeStruct, List<FKValue>> stfkMap, ISemanticTypeStruct sts, object signal, bool childAsUnique)

{

int id = -1;

if (sts.Unique || childAsUnique)

{

List<IFullyQualifiedNativeType> fieldValues = rsys.SemanticTypeSystem.GetFullyQualifiedNativeTypeValues(signal, sts.DeclTypeName, false);

id = InsertIfRecordDoesntExist(stfkMap, sts, signal, fieldValues, true);

}

else if (sts.SemanticElements.Any(se => se.UniqueField) || sts.NativeTypes.Any(nt => nt.UniqueField))

{

List<IFullyQualifiedNativeType> fieldValues = rsys.SemanticTypeSystem.GetFullyQualifiedNativeTypeValues(signal, sts.DeclTypeName, false).Where(fqnt => fqnt.NativeType.UniqueField).ToList();

id = InsertIfRecordDoesntExist(stfkMap, sts, signal, fieldValues, true);

}

else

{

id = Insert(stfkMap, sts, signal);

}

return id;

}

Not obvious is the fact that GetFullyQualifiedNativeTypeValues is returning structures that carry forward the parent element's uniqueness flag.

Not obvious is the fact that GetFullyQualifiedNativeTypeValues is returning structures that carry forward the parent element's uniqueness flag.

We have three states:

- The structure or a parent structure is flagged as unique. This treats all foreign key and native type fields as comprising the composite unique key.

- One or more child elements (implemented as a foreign key) is unique or one or more native type elements is unique. The unique composite key consists exclusively of the unique foreign key and native type fields.

- There is no unique key. In this case, the structure is always inserted.

Once we have some unique fields, we test to see whether it's unique and, if so insert it:

protected int InsertIfRecordDoesntExist(Dictionary<ISemanticTypeStruct, List<FKValue>> stfkMap, ISemanticTypeStruct sts, object signal, List<IFullyQualifiedNativeType> fieldValues, bool childAsUnique)

{

int id = -1;

bool exists = QueryUniqueness(stfkMap, sts, signal, fieldValues, out id, true);

if (!exists)

{

id = Insert(stfkMap, sts, signal);

}

return id;

}

The new record's primary key ID is returned or the existing ID is returned.

protected bool QueryUniqueness(Dictionary<ISemanticTypeStruct, List<FKValue>> stfkMap, ISemanticTypeStruct sts, object signal, List<IFullyQualifiedNativeType> uniqueFieldValues, out int id, bool allFKs = false)

{

id = -1;

bool ret = false;

List<FKValue> fkValues;

bool hasFKValues = stfkMap.TryGetValue(sts, out fkValues);

StringBuilder sb = BuildUniqueQueryStatement(hasFKValues, fkValues, sts, uniqueFieldValues, allFKs);

IDbCommand cmd = AddParametersToCommand(uniqueFieldValues, hasFKValues, fkValues, allFKs);

cmd.CommandText = sb.ToString();

LogSqlStatement(cmd.CommandText);

object oid = cmd.ExecuteScalar();

ret = (oid != null);

if (ret)

{

id = Convert.ToInt32(oid);

}

return ret;

}

And finally, if an insert is required, we have this rather unwieldy piece of code to actually perform the insert:

protected int Insert(Dictionary<ISemanticTypeStruct, List<FKValue>> stfkMap, ISemanticTypeStruct sts, object signal)

{

List<IFullyQualifiedNativeType> ntFieldValues = rsys.SemanticTypeSystem.GetFullyQualifiedNativeTypeValues(signal, sts.DeclTypeName, false);

StringBuilder sb = new StringBuilder("insert into " + sts.DeclTypeName + " (");

sb.Append(String.Join(", ", ntFieldValues.Select(f => f.Name)));

List<FKValue> fkValues;

bool hasFKValues = stfkMap.TryGetValue(sts, out fkValues);

if (hasFKValues && fkValues.Count > 0)

{

if (ntFieldValues.Count > 0) sb.Append(", ");

sb.Append(string.Join(", ", fkValues.Select(fkv => fkv.FieldName)));

}

sb.Append(") values (");

sb.Append(String.Join(", ", ntFieldValues.Select(f => "@" + f.Name)));

if (hasFKValues && fkValues.Count > 0)

{

if (ntFieldValues.Count > 0) sb.Append(", ");

sb.Append(string.Join(", ", fkValues.Select(fkv => "@" + fkv.FieldName)));

}

sb.Append(")");

IDbCommand cmd = dbio.CreateCommand();

ntFieldValues.ForEach(fv => cmd.Parameters.Add(dbio.CreateParameter(fv.Name, fv.Value)));

if (hasFKValues && fkValues.Count > 0)

{

fkValues.ForEach(fkv => cmd.Parameters.Add(dbio.CreateParameter(fkv.FieldName, fkv.ID)));

}

cmd.CommandText = sb.ToString();

LogSqlStatement(cmd.CommandText);

cmd.ExecuteNonQuery();

int id = dbio.GetLastID(sts.DeclTypeName);

return id;

}

A Simple Unique Key Insert Test

This test verifies that when we attempt to insert two identical records, the semantic database detects this, based on our semantic structure configuration, and ignores the second insert because it's a duplicate record.

This test verifies that when we attempt to insert two identical records, the semantic database detects this, based on our semantic structure configuration, and ignores the second insert because it's a duplicate record.

Recall how the non-unique LatLon semantic structure was initialized:

protected void InitLatLonNonUnique()

{

SemanticTypeStruct sts = Helpers.CreateSemanticType("LatLon", false, decls, structs);

Helpers.CreateNativeType(sts, "latitude", "double", false);

Helpers.CreateNativeType(sts, "longitude", "double", false);

}

In this unit test, we initialize the structure slightly differently:

protected void InitLatLonUniqueFields()

{

SemanticTypeStruct sts = Helpers.CreateSemanticType("LatLon", false, decls, structs);

Helpers.CreateNativeType(sts, "latitude", "double", <font color="#FF0000">true</font>);

Helpers.CreateNativeType(sts, "longitude", "double", <font color="#FF0000">true</font>);

}

);

Helpers.CreateNativeType(sts, "longitude", "double", true);

}

Notice in this structure, we are declaring that the native type fields are both unique. This composite key comprises the unique fields, and we see that the semantic database ends up inserting only one record.

A Simple Unique Structure Insert Test

Again, this test verifies that when we attempt to insert two identical records, the semantic database detects this, based on our semantic structure configuration, and ignores the second insert because it's a duplicate record. In this case though, it is the semantic structure itself that is flagged as unique:

Again, this test verifies that when we attempt to insert two identical records, the semantic database detects this, based on our semantic structure configuration, and ignores the second insert because it's a duplicate record. In this case though, it is the semantic structure itself that is flagged as unique:

protected void InitLatLonUniqueST()

{

SemanticTypeStruct sts = Helpers.CreateSemanticType("LatLon", <font color="#FF0000">true</font>, decls, structs);

Helpers.CreateNativeType(sts, "latitude", "double", false);

Helpers.CreateNativeType(sts, "longitude", "double", false);

}

Here we're testing (in a simple way) that if a structure is declared as unique, then we don't have to bother setting any native type fields anywhere in the hierarchy from here on as unique.

Two-Level Non-Unique Insert Test

Here we do something a bit more interesting -- we're going create a simple two-level structure: a parent "Restaurant" and a child "LatLon", and verify that we get two records in both the Restaurant and LatLon tables.

Here we do something a bit more interesting -- we're going create a simple two-level structure: a parent "Restaurant" and a child "LatLon", and verify that we get two records in both the Restaurant and LatLon tables.

First, let's look at the initialization of the semantic structure:

protected void InitRestaurantLatLonNonUnique()

{

SemanticTypeStruct stsRest = Helpers.CreateSemanticType("Restaurant", false, decls, structs);

SemanticTypeStruct stsLatLon = Helpers.CreateSemanticType("LatLon", false, decls, structs);

Helpers.CreateNativeType(stsLatLon, "latitude", "double", false);

Helpers.CreateNativeType(stsLatLon, "longitude", "double", false);

Helpers.CreateSemanticElement(stsRest, "LatLon", false);

}

We see that "Restaurant" has a "LatLon" element which is comprised of two native types, "latitude" and "longitude". Notice that "Restaurant" doesn't have any native types itself -- we don't really need or want any for this particular test -- we want to start simply.

On the database side, the semantic database creates the following tables (as described by Postgres):

On the database side, the semantic database creates the following tables (as described by Postgres):

CREATE TABLE restaurant

(

id serial NOT NULL,

fk_latlonid bigint,

CONSTRAINT restaurant_pkey PRIMARY KEY (id),

CONSTRAINT restaurant_fk_latlonid_fkey FOREIGN KEY (fk_latlonid)

REFERENCES latlon (id) MATCH SIMPLE

ON UPDATE NO ACTION ON DELETE NO ACTION

)

Notice the foreign key to the LatLon table (annoyingly, Postgres turns all tables and fields into lowercase).

The LatLon table hasn't changed:

CREATE TABLE latlon

(

id serial NOT NULL,

latitude double precision,

longitude double precision,

CONSTRAINT latlon_pkey PRIMARY KEY (id)

)

This unit test initializes the semantic structure slightly differently now because LatLon is an element of Restaurant:

[TestMethod]

public void TwoLevelNonUniqueSTInsert()

{

InitializeSDRTests(() => InitRestaurantLatLonNonUnique());

DropTable("Restaurant");

DropTable("LatLon");

sdr.Protocols = "LatLon; Restaurant";

sdr.ProtocolsUpdated();

ICarrier carrier = Helpers.CreateCarrier(rsys, "Restaurant", signal =>

{

<font color="#FF0000"> signal.LatLon.latitude = 1.0;

signal.LatLon.longitude = 2.0;

</font> });

sdr.ProcessCarrier(carrier);

IDbConnection conn = sdr.Connection;

int count;

IDbCommand cmd = conn.CreateCommand();

cmd.CommandText = "SELECT count(*) from LatLon";

count = Convert.ToInt32(cmd.ExecuteScalar());

Assert.AreEqual(1, count, "Expected 1 LatLon record.");

cmd.CommandText = "SELECT count(*) from Restaurant";

count = Convert.ToInt32(cmd.ExecuteScalar());

Assert.AreEqual(1, count, "Expected 1 Restaurant record.");

sdr.ProcessCarrier(carrier);

cmd.CommandText = "SELECT count(*) from LatLon";

count = Convert.ToInt32(cmd.ExecuteScalar());

Assert.AreEqual(2, count, "Expected 2 LatLon record.");

cmd.CommandText = "SELECT count(*) from Restaurant";

count = Convert.ToInt32(cmd.ExecuteScalar());

Assert.AreEqual(2, count, "Expected 2 Restaurant records.");

sdr.Terminate();

}

Two-Level Unique Structure Insert Test

Next, we want to see what happens when we create the LatLon structure, indicating that it is unique:

Next, we want to see what happens when we create the LatLon structure, indicating that it is unique:

protected void InitRestaurantLatLonUniqueChildST()

{

SemanticTypeStruct stsRest = Helpers.CreateSemanticType("Restaurant", false, decls, structs);

SemanticTypeStruct stsLatLon = Helpers.CreateSemanticType("LatLon", <font color="#FF0000">true</font>, decls, structs);

Helpers.CreateNativeType(stsLatLon, "latitude", "double", false);

Helpers.CreateNativeType(stsLatLon, "longitude", "double", false);

Helpers.CreateSemanticElement(stsRest, "LatLon", false);

}

As expected, when we attempt to insert two duplicate records, that LatLon structure is inserted only once and we get two Restaurant records pointing to the same LatLon record:

int count;

IDbCommand cmd = conn.CreateCommand();

cmd.CommandText = "SELECT count(*) from LatLon";

count = Convert.ToInt32(cmd.ExecuteScalar());

Assert.AreEqual(1, count, "Expected 1 LatLon record.");

cmd.CommandText = "SELECT count(*) from Restaurant";

count = Convert.ToInt32(cmd.ExecuteScalar());

Assert.AreEqual(1, count, "Expected 1 Restaurant record.");

sdr.ProcessCarrier(carrier);

cmd.CommandText = "SELECT count(*) from LatLon";

count = Convert.ToInt32(cmd.ExecuteScalar());

Assert.AreEqual(1, count, "Expected 1 LatLon record.");

cmd.CommandText = "SELECT count(*) from Restaurant";

count = Convert.ToInt32(cmd.ExecuteScalar());

Assert.AreEqual(2, count, "Expected 2 Restaurant records.");

Two-Level Unique Element Insert Test

A variation on this theme is creating the Restaurant-LatLon structure such that the LatLon element of the Restaurant structure is declared unique. In concrete terms, this tells the semantic database that the foreign key field "fk_latlonid" is a unique field. We initialize the structure in code like this:

A variation on this theme is creating the Restaurant-LatLon structure such that the LatLon element of the Restaurant structure is declared unique. In concrete terms, this tells the semantic database that the foreign key field "fk_latlonid" is a unique field. We initialize the structure in code like this:

protected void InitRestaurantLatLonUniqueParentSTElement()

{

SemanticTypeStruct stsRest = Helpers.CreateSemanticType("Restaurant", false, decls, structs);

SemanticTypeStruct stsLatLon = Helpers.CreateSemanticType("LatLon", false, decls, structs);

Helpers.CreateNativeType(stsLatLon, "latitude", "double", false);

Helpers.CreateNativeType(stsLatLon, "longitude", "double", false);

Helpers.CreateSemanticElement(stsRest, "LatLon", <font color="#FF0000">true</font>);

}

Here's our test (the earlier part of the test code is the same as in the previous cases):

int count;

IDbCommand cmd = conn.CreateCommand();

cmd.CommandText = "SELECT count(*) from LatLon";

count = Convert.ToInt32(cmd.ExecuteScalar());

Assert.AreEqual(1, count, "Expected 1 LatLon record.");

cmd.CommandText = "SELECT count(*) from Restaurant";

count = Convert.ToInt32(cmd.ExecuteScalar());

Assert.AreEqual(1, count, "Expected 1 Restaurant record.");

sdr.ProcessCarrier(carrier);

cmd.CommandText = "SELECT count(*) from LatLon";

count = Convert.ToInt32(cmd.ExecuteScalar());

Assert.AreEqual(2, count, "Expected 2 LatLon records.");

cmd.CommandText = "SELECT count(*) from Restaurant";

count = Convert.ToInt32(cmd.ExecuteScalar());

Assert.AreEqual(2, count, "Expected 2 Restaurant records.");

Because only the foreign key is unique, we will be inserting two LatLon records, as there are no fields declared unique in LatLon. Because this returns a new ID, the foreign key field is not unique, causing a second entry in the Restaurant table.

Two-Level Unique Element and Structure Insert Test

Finally, we test the combination where both the Restaurant's element LatLon (ie, it's foreign key) and the LatLon structure itself are unique. Here's how we configure the semantic structure:

Finally, we test the combination where both the Restaurant's element LatLon (ie, it's foreign key) and the LatLon structure itself are unique. Here's how we configure the semantic structure:

protected void InitRestaurantUniqueLatLonAndParentSTElement()

{

SemanticTypeStruct stsRest = Helpers.CreateSemanticType("Restaurant", false, decls, structs);

SemanticTypeStruct stsLatLon = Helpers.CreateSemanticType("LatLon", <font color="#FF0000">true</font>, decls, structs);

Helpers.CreateNativeType(stsLatLon, "latitude", "double", false);

Helpers.CreateNativeType(stsLatLon, "longitude", "double", false);

Helpers.CreateSemanticElement(stsRest, "LatLon", <font color="#FF0000">true</font>);

}

Now we see that, because the structure LatLon is unique and the LatLon element in Restaurant is unique (implemented as the foreign key) we get one Restaurant record and one LatLon record when we attempt to insert two identical records:

int count;

IDbCommand cmd = conn.CreateCommand();

cmd.CommandText = "SELECT count(*) from LatLon";

count = Convert.ToInt32(cmd.ExecuteScalar());

Assert.AreEqual(1, count, "Expected 1 LatLon record.");

cmd.CommandText = "SELECT count(*) from Restaurant";

count = Convert.ToInt32(cmd.ExecuteScalar());

Assert.AreEqual(1, count, "Expected 1 Restaurant record.");

sdr.ProcessCarrier(carrier);

cmd.CommandText = "SELECT count(*) from LatLon";

count = Convert.ToInt32(cmd.ExecuteScalar());

Assert.AreEqual(1, count, "Expected 1 LatLon record.");

cmd.CommandText = "SELECT count(*) from Restaurant";

count = Convert.ToInt32(cmd.ExecuteScalar());

Assert.AreEqual(1, count, "Expected 1 Restaurant record.");

Since this is all very complicated, let's test your comprehension. What happens when the semantic structure is declared like this:

Since this is all very complicated, let's test your comprehension. What happens when the semantic structure is declared like this:

protected void InitRestaurantUniqueLatLonAndParentSTElement()

{

SemanticTypeStruct stsRest = Helpers.CreateSemanticType("Restaurant", <font color="#FF0000">true</font>, decls, structs);

SemanticTypeStruct stsLatLon = Helpers.CreateSemanticType("LatLon", false, decls, structs);

Helpers.CreateNativeType(stsLatLon, "latitude", "double", false);

Helpers.CreateNativeType(stsLatLon, "longitude", "double", false);

Helpers.CreateSemanticElement(stsRest, "LatLon", true);

}

Yes indeed, because the Restaurant structure is itself declared as unique, every child element inherits its parent's uniqueness, and again we will insert only one actual record for two or more attempts of a duplicate semantic structure value.

A Simple Query Test

If you thought inserting data was complicated, getting it back out of the database is even more complicated because of the inferences that the semantic database makes regarding how to join to disparate semantic structures. Querying consists of:

If you thought inserting data was complicated, getting it back out of the database is even more complicated because of the inferences that the semantic database makes regarding how to join to disparate semantic structures. Querying consists of:

- Determining the native type fields

- Build the list of joins required to drill down into child elements

- Resolve physical table and field names in the order by clause

- Resolve physical table and field names in the where clause (currently not implemented)

- Add the database-specific implementation of a row return limit

- In a multi-structure join, infer the linkages between structures and implement them as additional table joins

- Execute the query

- Hydrate semantic instances with the data from each returned row

Let's start with a basic single structure query:

[TestMethod]

public void SimpleQuery()

{

InitializeSDRTests(() => InitLatLonNonUnique());

DropTable("Restaurant");

DropTable("LatLon");

sdr.Protocols = "LatLon";

sdr.ProtocolsUpdated();

sdr.UnitTesting = true;

ICarrier latLonCarrier = Helpers.CreateCarrier(rsys, "LatLon", signal =>

{

signal.latitude = 1.0;

signal.longitude = 2.0;

});

sdr.ProcessCarrier(latLonCarrier);

ICarrier queryCarrier = Helpers.CreateCarrier(rsys, "Query", signal =>

{

signal.QueryText = "LatLon";

});

sdr.ProcessCarrier(queryCarrier);

List<QueuedCarrierAction> queuedCarriers = rsys.QueuedCarriers;

Assert.AreEqual(1, queuedCarriers.Count, "Expected one signal to be returned.");

dynamic retSignal = queuedCarriers[0].Carrier.Signal;

Assert.AreEqual(1.0, retSignal.latitude, "Wrong data for latitude.");

Assert.AreEqual(2.0, retSignal.longitude, "Wrong data for longitude.");

}

Because we're using the HOPE architecture, there is actually no receiving carrier for the resulting record, so we inspect the queue, which is simpler than adding the necessary scaffolding in our unit tests to receive the carrier.

Because we're using the HOPE architecture, there is actually no receiving carrier for the resulting record, so we inspect the queue, which is simpler than adding the necessary scaffolding in our unit tests to receive the carrier.

The single-structure query implementation is basically what you would expect:

The single-structure query implementation is basically what you would expect:

protected void QueryDatabase(string query)

{

string maxRecords = null;

List<string> types;

List<string> orderBy;

Preprocess(query, out maxRecords, out types, out orderBy);

if (types.Count() == 1)

{

string protocol = types[0];

AddEmitProtocol(protocol);

ISemanticTypeStruct sts = rsys.SemanticTypeSystem.GetSemanticTypeStruct(protocol);

List<object> signals = QueryType(protocol, String.Empty, orderBy, maxRecords);

EmitSignals(signals, sts);

}

else ...

Again, because the semantic database is actually a receptor, any newly encountered protocol is added to the list of protocols that the database emits. Hence the line

Again, because the semantic database is actually a receptor, any newly encountered protocol is added to the list of protocols that the database emits. Hence the line AddEmitProtocol.

The method QueryType puts all the pieces together to execute the query:

protected List<object> QueryType(string protocol, string where, List<string> orderBy, string maxRecords)

{

ISemanticTypeStruct sts = rsys.SemanticTypeSystem.GetSemanticTypeStruct(protocol);

List<string> fields = new List<string>();

List<string> joins = new List<string>();

Dictionary<ISemanticTypeStruct, int> structureUseCounts = new Dictionary<ISemanticTypeStruct, int>();

List<Tuple<string, string>> fqntAliases = new List<Tuple<string, string>>();

BuildQuery(sts, fields, joins, structureUseCounts, sts.DeclTypeName, fqntAliases);

string sqlQuery = CreateSqlStatement(sts, fields, joins, fqntAliases, where, orderBy, maxRecords);

List<object> ret = PopulateSignals(sqlQuery, sts);

return ret;

}

Very important in this process is the recursive BuildQuery, which traverses the semantic structure, following child elements and creating the necessary joins as well as picking up any native types along the way:

protected void BuildQuery(ISemanticTypeStruct sts, List<string> fields, List<string> joins, Dictionary<ISemanticTypeStruct, int> structureUseCounts, string fqn, List<Tuple<string, string>> fqntAliases)

{

string parentName = GetUseName(sts, structureUseCounts);

sts.NativeTypes.ForEach(nt =>

{

string qualifiedFieldName = fqn + "." + nt.Name;

string qualifiedAliasFieldName = parentName + "." + nt.Name;

fields.Add(qualifiedAliasFieldName);

fqntAliases.Add(new Tuple<string, string>(qualifiedFieldName, qualifiedAliasFieldName));

});

sts.SemanticElements.ForEach(child =>

{

ISemanticTypeStruct childsts = child.Element.Struct;

IncrementUseCount(childsts, structureUseCounts);

string asChildName = GetUseName(childsts, structureUseCounts);

joins.Add("left join " + childsts.DeclTypeName + " as " + asChildName + " on " + asChildName + ".ID = " + parentName + ".FK_" + childsts.DeclTypeName + "ID");

BuildQuery(childsts, fields, joins, structureUseCounts, fqn+"."+childsts.DeclTypeName, fqntAliases);

});

}

Once that's done, the actual SQL select statement can be created:

protected string CreateSqlStatement(ISemanticTypeStruct sts, List<string> fields, List<string> joins, List<Tuple<string, string>> fqntAliases, string where, List<string> orderBy, string maxRecords)

{

string sqlQuery = "select " + String.Join(", ", fields) + " \r\nfrom " + sts.DeclTypeName + " \r\n" + String.Join(" \r\n", joins);

sqlQuery = sqlQuery + " " + ParseOrderBy(orderBy, fqntAliases);

sqlQuery = dbio.AddLimitClause(sqlQuery, maxRecords);

return sqlQuery;

}

Once we've acquired the reader, we can iterate through the records and create the signals to be emitted:

protected List<object> PopulateSignals(string sqlQuery, ISemanticTypeStruct sts)

{

List<object> ret = new List<object>();

IDataReader reader = AcquireReader(sqlQuery);

while (reader.Read())

{

object outsignal = rsys.SemanticTypeSystem.Create(sts.DeclTypeName);

int counter = 0;

Populate(sts, outsignal, reader, ref counter);

ret.Add(outsignal);

}

reader.Close();

return ret;

}

The actual population of the signal's fields is again recursive and dependent upon the same order in which fields were generated for the query statement. Here we are using reflection to set the values as we drill into the semantic structure:

protected bool Populate(ISemanticTypeStruct sts, object signal, IDataReader reader, ref int parmNumber)

{

List<object> vals = new List<object>();

bool anyNonNull = false;

for (int i = 0; i < sts.NativeTypes.Count; i++)

{

vals.Add(reader[parmNumber++]);

}

sts.NativeTypes.ForEachWithIndex((nt, idx) =>

{

object val = vals[idx];

if (val != DBNull.Value)

{

Assert.TryCatch(() => nt.SetValue(rsys.SemanticTypeSystem, signal, val), (ex) => EmitException(ex));

anyNonNull = true;

}

});

foreach (ISemanticElement child in sts.SemanticElements)

{

ISemanticTypeStruct childsts = child.Element.Struct;

PropertyInfo piSub = signal.GetType().GetProperty(child.Name);

object childSignal = piSub.GetValue(signal);

anyNonNull |= Populate(childsts, childSignal, reader, ref parmNumber);

}

return anyNonNull;

}

In the single structure query, we don't really care whether there are any non-null fields. The return value of the Populate method is however used when working with multi-structure queries, as all-null fields for a structure sets the structure to null. Also,

In the single structure query, we don't really care whether there are any non-null fields. The return value of the Populate method is however used when working with multi-structure queries, as all-null fields for a structure sets the structure to null. Also, parmNumber is again something that comes into play in a multi-structure query.

Alias Query Test

This test does a simple check that table and field name aliases are used. The semantic structure is set up as follows:

This test does a simple check that table and field name aliases are used. The semantic structure is set up as follows:

protected void InitPersonStruct()

{

SemanticTypeStruct stsText = Helpers.CreateSemanticType("Text", false, decls, structs);

Helpers.CreateNativeType(stsText, "Value", "string", false);

SemanticTypeStruct stsFirstName = Helpers.CreateSemanticType("FirstName", false, decls, structs);

Helpers.CreateSemanticElement(stsFirstName, "Text", false);

SemanticTypeStruct stsLastName = Helpers.CreateSemanticType("LastName", false, decls, structs);

Helpers.CreateSemanticElement(stsLastName, "Text", false);

SemanticTypeStruct stsPerson = Helpers.CreateSemanticType("Person", false, decls, structs);

Helpers.CreateSemanticElement(stsPerson, "LastName", false);

Helpers.CreateSemanticElement(stsPerson, "FirstName", false);

}

Here, Person consists of FirstName and LastName, both of which reference the Text structure. This requires two joins to the Text table which means the table has to be aliased. The field name, being the same, must be aliased as well.

In the semantic database, this is accomplished by keeping track of the table usage and incrementing a counter for each usage:

In the semantic database, this is accomplished by keeping track of the table usage and incrementing a counter for each usage:

protected string GetUseName(ISemanticTypeStruct sts, Dictionary<ISemanticTypeStruct, int> structureUseCounts)

{

int count;

string ret = sts.DeclTypeName;

if (structureUseCounts.TryGetValue(sts, out count))

{

ret = ret + count;

}

return ret;

}

The resulting query looks like this:

select <font color="#FF0000">Text1</font>.Value, <font color="#FF0000">Text2</font>.Value

from Person

left join LastName as <font color="#FF0000">LastName1</font> on LastName1.ID = Person.FK_LastNameID

left join Text as <font color="#FF0000">Text1</font> on Text1.ID = LastName1.FK_TextID

left join FirstName as <font color="#FF0000">FirstName1</font> on FirstName1.ID = Person.FK_FirstNameID

left join Text as <font color="#FF0000">Text2</font> on Text2.ID = FirstName1.FK_TextID

Notice the "as" statements. For convenience, every table is aliased. This is essential for multi-structure joins.

Unique Key Join

There are three ways to join structures: by their unique key fields, the structure being declared unique, or by a structure's unique elements. The latter two resolve to unique key fields, but still requires testing (the test after this one.) Here, we test that a shared structure, which is declared as unique, allows the semantic database to infer that the two parent structures can be joined. The structures are defined like this:

There are three ways to join structures: by their unique key fields, the structure being declared unique, or by a structure's unique elements. The latter two resolve to unique key fields, but still requires testing (the test after this one.) Here, we test that a shared structure, which is declared as unique, allows the semantic database to infer that the two parent structures can be joined. The structures are defined like this:

protected void InitFeedUrlWithUniqueStruct()

{

SemanticTypeStruct stsUrl = Helpers.CreateSemanticType("Url", <font color="#FF0000">true</font>, decls, structs);

Helpers.CreateNativeType(stsUrl, "Value", "string", false);

SemanticTypeStruct stsVisited = Helpers.CreateSemanticType("Visited", false, decls, structs);

Helpers.CreateSemanticElement(stsVisited, "Url", false);

Helpers.CreateNativeType(stsVisited, "Count", "int", false);

SemanticTypeStruct stsFeedUrl = Helpers.CreateSemanticType("RSSFeedUrl", false, decls, structs);

Helpers.CreateSemanticElement(stsFeedUrl, "Url", false);

}

A common structure, Url, is created as being unique. Both the Visited and RSSFeedURl structures reference Url.

The unit test sets up two "feed" entries:

However, the visited only references http://localhost (sorry Code Project!)

protected void TwoStructureJoinTest()

{

DropTable("Url");

DropTable("Visited");

DropTable("RSSFeedUrl");

sdr.Protocols = "RSSFeedUrl; Visited";

sdr.ProtocolsUpdated();

sdr.UnitTesting = true;

ICarrier feedUrlCarrier1 = Helpers.CreateCarrier(rsys, "RSSFeedUrl", signal =>

{

signal.Url.Value = "http://localhost";

});

ICarrier feedUrlCarrier2 = Helpers.CreateCarrier(rsys, "RSSFeedUrl", signal =>

{

signal.Url.Value = "http://www.codeproject.com";

});

ICarrier visitedCarrier = Helpers.CreateCarrier(rsys, "Visited", signal =>

{

signal.Url.Value = "http://localhost";

signal.Count = 1;

});

sdr.ProcessCarrier(feedUrlCarrier1);

sdr.ProcessCarrier(feedUrlCarrier2);

sdr.ProcessCarrier(visitedCarrier);

ICarrier queryCarrier = Helpers.CreateCarrier(rsys, "Query", signal =>

{

signal.QueryText = "RSSFeedUrl, Visited";

});

sdr.ProcessCarrier(queryCarrier);

List<QueuedCarrierAction> queuedCarriers = rsys.QueuedCarriers;

Assert.AreEqual(2, queuedCarriers.Count, "Expected two signals to be returned.");

dynamic retSignal = queuedCarriers[0].Carrier.Signal;

Assert.AreEqual("http://localhost", retSignal.RSSFeedUrl.Url.Value, "Unexpected URL value.");

Assert.AreEqual(1, retSignal.Visited.Count);

retSignal = queuedCarriers[1].Carrier.Signal;

Assert.AreEqual("http://www.codeproject.com", retSignal.RSSFeedUrl.Url.Value, "Unexpected URL value.");

Assert.AreEqual(null, retSignal.Visited);

}

We see from the query how it is joining the two tables:

We see from the query how it is joining the two tables:

select Url1.Value, Visited.Count, Url2.Value

from RSSFeedUrl

left join Url as Url1 on Url1.ID = RSSFeedUrl.FK_UrlID

left join Visited on Visited.FK_UrlID = RSSFeedUrl.FK_UrlID

left join Url as Url2 on Url2.ID = Visited.FK_UrlID

And note how the data is returned:

The second row shows us the we do not have an associated Visited record for http://www.codeproject.com. Because the Visited structure's fields are all null, the semantic database sets the instance to null, which is tested here:

The second row shows us the we do not have an associated Visited record for http://www.codeproject.com. Because the Visited structure's fields are all null, the semantic database sets the instance to null, which is tested here:

retSignal = queuedCarriers[1].Carrier.Signal;

Assert.AreEqual("http://www.codeproject.com", retSignal.RSSFeedUrl.Url.Value, "Unexpected URL value.");

<font color="#FF0000">Assert.AreEqual(null, retSignal.Visited);</font>

Also observe that the structure returned has been created at runtime by the semantic database. The returning signal consists of a root semantic type whose elements are the joined structures. Thus, in the above query, we get back the following structure:

Also observe that the structure returned has been created at runtime by the semantic database. The returning signal consists of a root semantic type whose elements are the joined structures. Thus, in the above query, we get back the following structure:

Or, as I prefer to diagram semantic structures so that the native types are all at the top:

What happens we try to join multiple semantic structures?

What happens we try to join multiple semantic structures?

First, we need to discover the correct join order, such that tables are declared in the SQL join before they are referenced. While this is not a requirement for all database engines, I have noted that SQLite is definitely not happy if it sees a reference to table that hasn't been declared in a join yet. So, we can now begin walking through the code in this path:

else if (types.Count() > 1)

{

Dictionary<string, List<Tuple<ISemanticTypeStruct, ISemanticTypeStruct>>> stSemanticTypes = new Dictionary<string, List<Tuple<ISemanticTypeStruct, ISemanticTypeStruct>>>();

Dictionary<TypeIntersection, List<ISemanticTypeStruct>> typeIntersectionStructs = new Dictionary<TypeIntersection, List<ISemanticTypeStruct>>();

Dictionary<ISemanticTypeStruct, int> structureUseCounts = new Dictionary<ISemanticTypeStruct, int>();

List<TypeIntersection> joinOrder = DiscoverJoinOrder(types, stSemanticTypes, typeIntersectionStructs);

...

DiscoverJoinOrder looks simple...

protected List<TypeIntersection> DiscoverJoinOrder(List<string> types, Dictionary<string, List<Tuple<ISemanticTypeStruct, ISemanticTypeStruct>>> stSemanticTypes, Dictionary<TypeIntersection, List<ISemanticTypeStruct>> typeIntersectionStructs)

{

foreach (string st in types)

{

stSemanticTypes[st] = rsys.SemanticTypeSystem.GetAllSemanticTypes(st);

}

List<TypeIntersection> joinOrder = GetJoinOrder(types, stSemanticTypes, typeIntersectionStructs);

return joinOrder;

}

... but it's deceptive, because the real work is in GetJoinOrder. This function is not very efficient, but it gets the job done for now. The concept is:

- Starting with the first structure (the root structure), try and join it with some other following structure.

- Once we've found a shared structure, remove it from the list and start over again, trying to resolve the next structure in the join list.

This process ensures that we create joins so that they are declared before being referenced by other joins:

protected List<TypeIntersection> GetJoinOrder(List<string> types, Dictionary<string, List<Tuple<ISemanticTypeStruct, ISemanticTypeStruct>>> stSemanticTypes, Dictionary<TypeIntersection, List<ISemanticTypeStruct>> typeIntersectionStructs)

{

List<TypeIntersection> joinOrder = new List<TypeIntersection>();

List<string> typesToJoin = new List<string>();

typesToJoin.AddRange(types.Skip(1));

int baseIdx = 0;

while (typesToJoin.Count > 0)

{

int idx = 0;

bool found = false;

foreach (string typeToJoin in types)

{

if (!typesToJoin.Contains(typeToJoin))

{

++idx;

continue;

}

List<ISemanticTypeStruct> sharedStructs = stSemanticTypes[types[baseIdx]].Select(t1 => t1.Item1).Intersect(stSemanticTypes[types[idx]].Select(t2 => t2.Item1)).ToList();

if (sharedStructs.Count > 0)

{

TypeIntersection typeIntersection = new TypeIntersection(types[baseIdx], types[idx]);

typeIntersectionStructs[typeIntersection] = sharedStructs;

joinOrder.Add(typeIntersection);

typesToJoin.Remove(types[idx]);

found = true;

break;

}

++idx;

}

if (found)

{

baseIdx = 0;

}

else

{

throw new Exception("Cannot find a common type for the required join.");

}

}

return joinOrder;

}

We continue setting up various structures that will be used for constructing the full query and build the pieces for the first (root) semantic structure:

List<ISemanticTypeStruct> sharedStructs = typeIntersectionStructs[joinOrder[0]];

ISemanticTypeStruct sharedStruct = sharedStructs[0];

string baseType = joinOrder[0].BaseType;

ISemanticTypeStruct parent0 = stSemanticTypes[baseType].Single(t => t.Item1 == sharedStruct).Item2;

bool parent0ElementUnique = parent0.SemanticElements.Any(se => se.Name == sharedStruct.DeclTypeName && se.UniqueField);

ISemanticTypeStruct sts0 = rsys.SemanticTypeSystem.GetSemanticTypeStruct(baseType);

List<string> fields0 = new List<string>();